Image via Mike Campbell

Steven Louis missed the part where we stopped getting bankrolls.

It’s almost five years to the day that Jason Jamal Jackson was forcibly relocated from a velvet lavender throne in Watts to solitary confinement in Abilene, TX, a city which resisted school integration for 15 years after Brown v. Board of Education. The mixed-custody Middleton Unit where Greedo was caged is lined by four armed outpost towers and double-chain fences laced with razor wire. It’s a hellish fate for any drug “offender,” but this sentencing felt like cruelty for sport. Jason Jackson becoming 03 Greedo was a lifelong parlay at an impossible handicap. His father died in a motorcycle accident when he was just one year old; poverty trapped him in concurrent ciphers of homelessness and incarceration; his shortfall of industry capital and a proud Grape Street Crip affiliation meant that mobilizing support across Los Angeles was an exhaustive battle.

Greedo emerged from all that with Moncler goggles and LIVING LEGEND inscribed on his face, not so much conquering his trauma as claiming and rerocking it. Sprawl, payola and gang politics all make it prohibitively difficult to score a Los Angeles anthem; a conservative estimate would give Greedo a full dozen of them, mostly self-produced and coming live from the Jordan Downs Projects. To scrap all that for drug and firearm possession uncovered through a chance traffic stop halfway across the country? Did torturing Greedo out of sight make Texas feel safe? Or was it because the very American journey of Jason Jackson was never allowed to be safe? We know the truth.

It is Friday, June 16, the night of Greedo’s first homecoming show in a half a decade. The line to get into The Novo snakes through LA Live, the $3 billion sterile entertainment fortress built on the part of downtown that historian Mike Davis called “the junkyard of dreams.” Save for when the Lakers are hosting, this is the type of place for people in Los Angeles who openly resent Los Angeles. But Greedo’s whole career has been an exercise in working around limitation and subverting what’s comfortable. Ten miles and a galaxy removed from Jordan Downs, The Novo has been dyed purple and fitted for a Drummer Gang chain.

As you enter, you see an Awful Lot Of Cough Syrup popup with GREEDO’S HOME merch. The group of women behind me are conveying their excitement by way of punctuated Shoreline Mafia adlibs. Cypress Moreno, a multi-hyphenate DJ hailing from Westlake by way of San Fernando, sends the room up with FrostyDaSnowmann’s “OMG.” Toward the end of the warmup set, he deploys a cheap party trick that’s ostensibly necessary for spaces like The Novo: he asks for the ladies to sing this one and put on “Party in the USA.” In a moment of cosmic affirmation, the reaction was reasonably flat and ultimately choked out by “Mr. Get Dough,” a 2500-person party basking in the fantasticness of being a joint and hitting a modified paisa dance. If Low End Theory is shuttered, Live Nation is pillaging and 92.3 won’t play the Stincs, where is the culture encouraged to congregate? If the city’s champion griots and marathon runners are getting taken down, where are you supposed to find refuge?

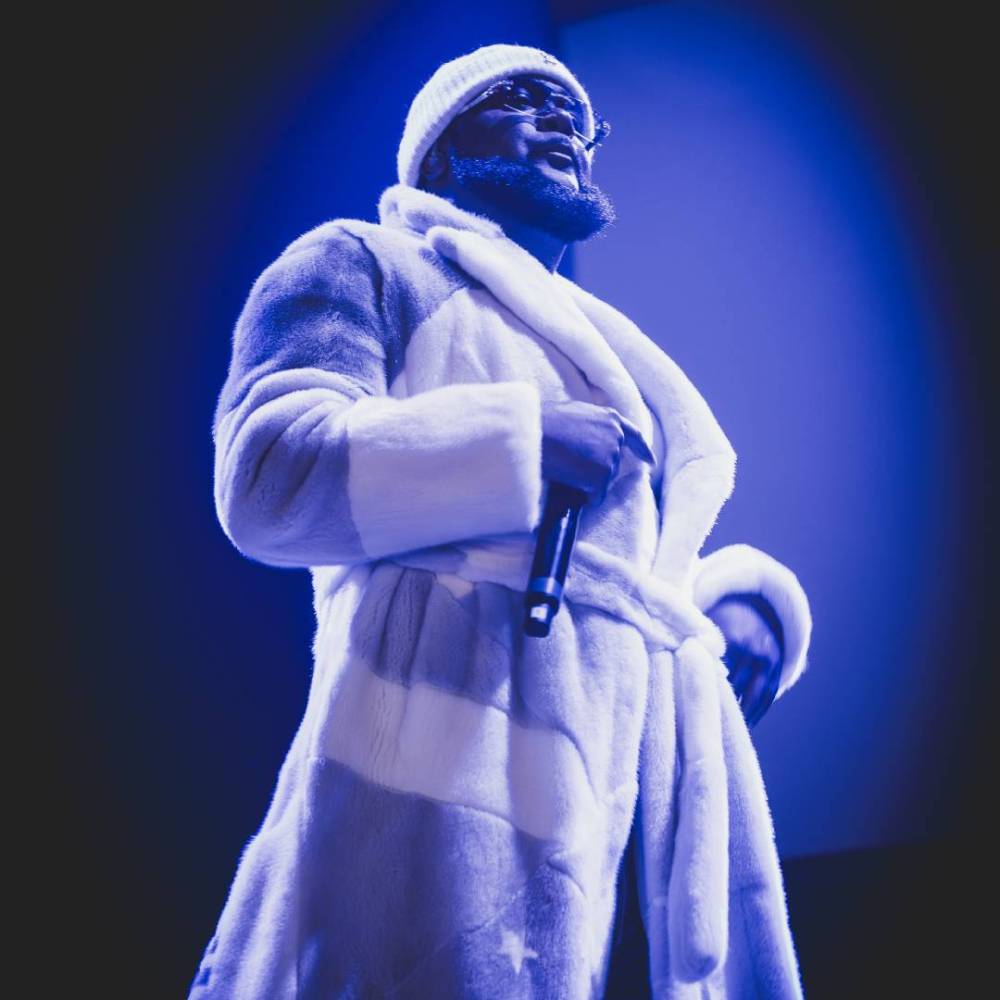

Greedo pops out, walking across the stage like a victorious gladiator. Cartier frames, Denim Tears jeans, a white and gray Louis Vuitton-by-Virgil mink that runs for $50K. He looks relieved, grinning and pacing around while occasionally peeping behind his shoulder for his folks. Amid the wall of sound, it seems most people here underestimated just how herculean this performance would be: Greedo was not only physically present, but a commanding and inviting performer betraying his years in isolation. That the man started off with an unreleased song is the most patently audacious part of all this, and though of course no one knows the words, “Rich On Grape Street” is heavy artillery. “Wockhardt spilled on my Margielas / I got rich and all y’all jealous,” he wails through black and purple minor synths that sound almost like the “Never Bend” beat was uncoiled. It recalls a recent admission from Weezy to Andre Gee that his favorite song is whichever his next song is. It reflects a mind deeply committed to prolific output, but it also makes sure things are positioned straight ahead. After everything Greedo’s been subjected to, and in a robe this fly, why would we look in any other direction? “I’m back, that shit easy,” he mutters into the mic just five minutes in.

Greedo is not the first Black musician to have time stolen from his prime, and unless the revolution is realized real fast, he’s not going to be the last one. As he shouts in the latest single, “Bacc Like I Never Left,” he can’t even drop his favorite rapper’s SLATT adlib without possibly getting prosecuted. Still, a citywide coronation of this breadth has few precedents. After beating his double murder charge and doing 23 hours of solitary confinement for five years, Baton Rouge folk hero Lil Boosie’s first show out looked undeniably historic, but it was also in Nashville. After doing a bid at Rikers Island for weapons charges, Lil Wayne’s first post-carceral performance was in Las Vegas. Not since the winning side of The State v. Radric Davis tore down Atlanta’s Esso Club have we seen some shit like this. Save for two short and sealed SXSW sets while he was required to stay in a Texas halfway house, this is his first time performing in half a decade. It’s a homecoming in the truest sense.

The hits take on a spiritual, even aggressive quality. Greedo flexes considerable vocal talent on the live runs of “Sweet Lady” and “Run For Your Life,” inflating and unwinding his croon without breaking posture. The stench of liquor is suddenly and appropriately strong during “Mafia Business,” and you can see multiple people tapping tattoo spots on “Never Bend.” But there’s a level of movement to the proceedings that wards off the gravity. There are multiple outfit changes, including a glacier Avirex puffer and a tri-patterned pink Prada shirt that would’ve made Prince blush. The original frequencies of Tookie and Raymond are clearly still good here; this is for everybody who held the city down. Ralfy the Plug rocks “Slime Me Up” with the barrel-out flow of Golden Era raps, a marked departure from the studio version, before covering his brother Drakeo’s verse on “Out The Slums,” which Greedo spits so forcefully that he nearly topples over. They cover “Something That I Did” with fallen Stinc Team soldier Ketchy the Great to conjure the extraterrestrial pimp and lace him with a renewed Perc script.

BlueBucksClan volleys bars back and forth with first-week-of-summer giddiness; Kalan FrFr tackles Greedo with a bear hug; a shirtless ASM Bopster delights and potentially terrifies. Watts owns the place tonight, but South Central is deep in the building, and near the end of the night, Long Beach ascendant Saviii 3rd rolls through for electrifying new shit with Daygo Made It. Brazen as it may sound, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to shuffle out of the show thinking that The Wolf’s most compelling music is still to come.

It’s only at the very end of the night that Greedo shows any sign of fatigue, and even then, nothing in his catalog is better suited for half-fried vocals than “Substance.” It doesn’t really look like physical exhaustion, just the static feeling in your head that comes with a cresting amphetamine rush. The song ends with his daughter Meilani in his arms, and in a moment wholly encapsulating the Purple Summer experience, he wipes her weeping eyes as she bops to the bridge of “take some’n, shake some’n, pop it like some ecstasy.”

It reinforces the necessity of a live space to understand Greedo. How does the emo-gangbanger anthem merchant connect to so many people despite such searing specificity? Why are we crying about Lil Money’s trap house being low on molly? Why weren’t we able to get together and do all this before? “On Crip, on Grape, I can’t believe this,” he says to the crowd. “I have to hold back tears. I gotta thank my city. Black, Mexican, White, Chinese, Filipino. Every race that they got out this motherf*cker, y’all kept me cool and kept me rich in jail.” It’s like he’s fully reconciling how many souls he’s transported to and from Jordan Downs, the sheer number of ears that have heard these walls spitting bars. Why is he asking if we feel safe before we all peel off on our separate ways? Being is so easily compromised, by the mundanity of an accident, gossiping lovers or insatiably jealous opps, bloodless pigs in perpetual hunting season. But the feeling, this shit right here? Finally, nothing is stopping that now.