Support real, independent music journalism by subscribing to Passion of the Weiss on Patreon.

Will Hagle knows that Hot Girl Summer may be over, but he’s looking forward to the start of ugly grown man who cares too much about college football season.

Before he ever made it to the table, Freddie Gibbs’s story had more ups and downs than a game of craps. By the time he got his first major label deal from Interscope in the middle of the 00s, he’d already survived the streets of Gary, left his football scholarship at Ball State, and endured a mandated military boot camp. Then the industry that scooped him up dropped him as soon as his brand of lyrically-driven gangster rap failed to adapt to the changing pop-rap landscape – or proved to not fit within it.

Betting on himself, Gibbs rolled the dice on a string of self-released mixtapes. A crowd began to form. The cheers grew louder as it all kept hitting. From Krayzie Bone to Bun B to Daz Dillinger and Spice-1, Gibbs’s idols bestowed him with cameos and support. Jeezy popped up from under the table, yelled, “Yeaaaaaah!” and almost burned all Gibbs’ chips with his bad energy. Momentum picked up again until the deafening silence following his arrest in France, his extradition to Austria, his show trial abroad, and his uncertain verdict in the court of public opinion back home. He crapped out. But he never stopped betting on himself. Now he’s raking in results no one could have predicted when his run began nearly two decades ago: undeniable, charisma-driven superstardom, a Grammy nomination, a feature film acting debut at Cannes, and renewed respect from a populace – which, if the ruling in Austria wasn’t a resounding, unanimous innocent verdict – would have left him with nothing.

The hype-fueled buildup to the casino-themed Soul Sold Separately, Freddie’s first release since 2021’s Alfredo, and his return to a partnership with a major label after a decade-plus of independence, is positioning Gibbs to hit his first legitimate jackpot. Like every work in his extensive discography, Soul Sold Separately is another demonstration of Gibbs’ pure rap ability. Consistency has long been his greatest attribute. He can rap his damn ass off and we know that by now. The technical precision has never faltered. What has changed are the superfluous elements surrounding his writing and delivery, like song construction and melodic experimentation.

This newest album is bigger, flashier, and more ambitious than anything in the catalog that precedes it, but it also adheres to a tested and proven template. A feature list featuring a mix of contemporary stars (Moneybagg Yo), unexpectedly sensical producers (James Blake), and under-appreciated legends (DJ Paul). And a packed roster beyond those few mentioned names, bolstered by a Warner Records budget. “Pain and Strife” is the obligatory Bone Thugs/Do or Die speed-rap track with a harmonized chorus. “Grandma’s Stove” is the introspective storytelling cut like Piñata’s “Knicks,” with deeper self-analysis but the same sequencing toward the end of the tracklist. “Space Rabbit” also dips into self-contextualization of the rapper’s past, with Gibbs admitting he once wanted to sound like G-Unit. That honest assessment of his early style is a throwaway line, but highlights his tonal evolution. What does Freddie Gibbs sound like now? Has he once again found a new way to sound like himself?

Soul Sold Separately shows how Freddie’s moved beyond the media comparisons or chameleon-like attempts to mesh with modern sounds that have held him back, in one way or another, over the years. After he first blew up, around 2009’s Miseducation of Freddie Gibbs and Midwestboxframecadillacmuzik, some incorrect skeptics designated Gibbs as a throwback gangster rapper living and recording in the wrong era. Always in the wrong era, it was the current era that caught up to Gibbs. Now, he’s the same artist he’s always been. A little older, a little better. On another upswing. At least now the masses around the table recognize the blend of natural talent and unnatural hardworking resilience in his persistent dice tosses: the work of an identifiable voice who, through forays into production others won’t touch, and by being his charming self, has formed a wholly unique sound.

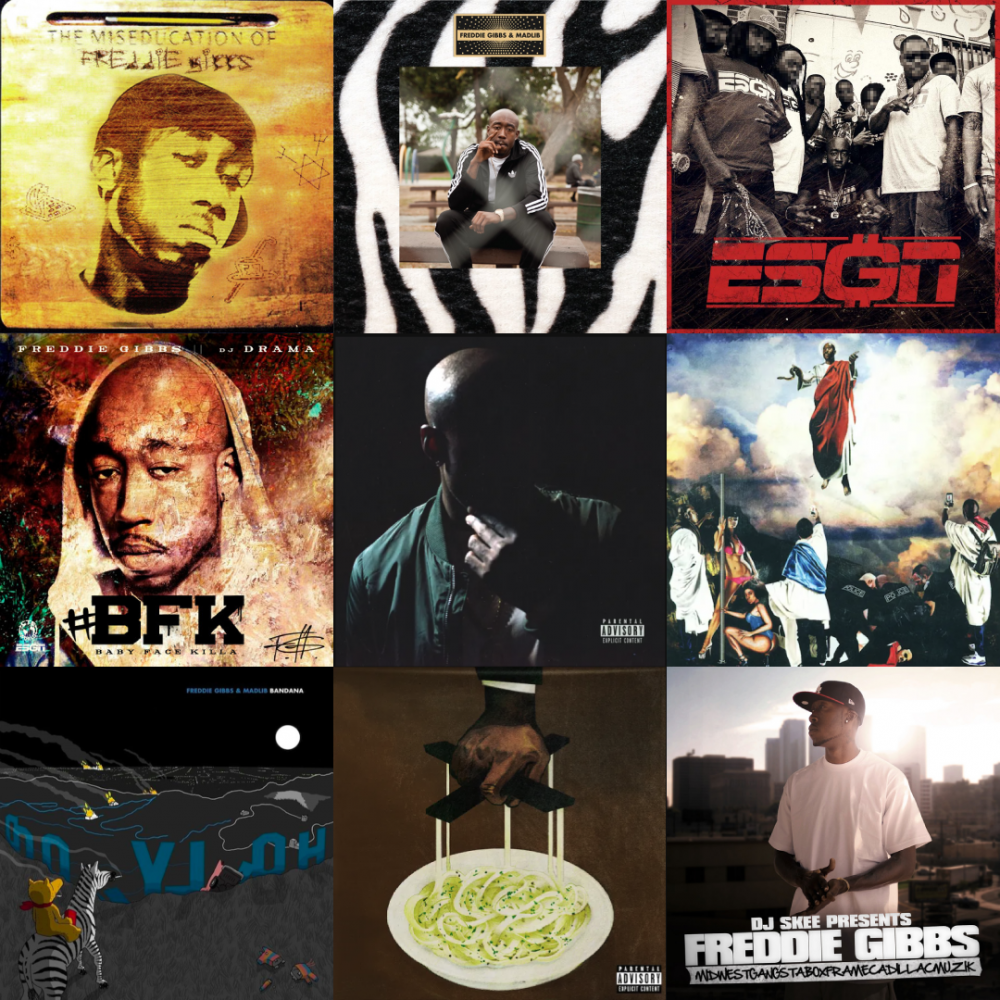

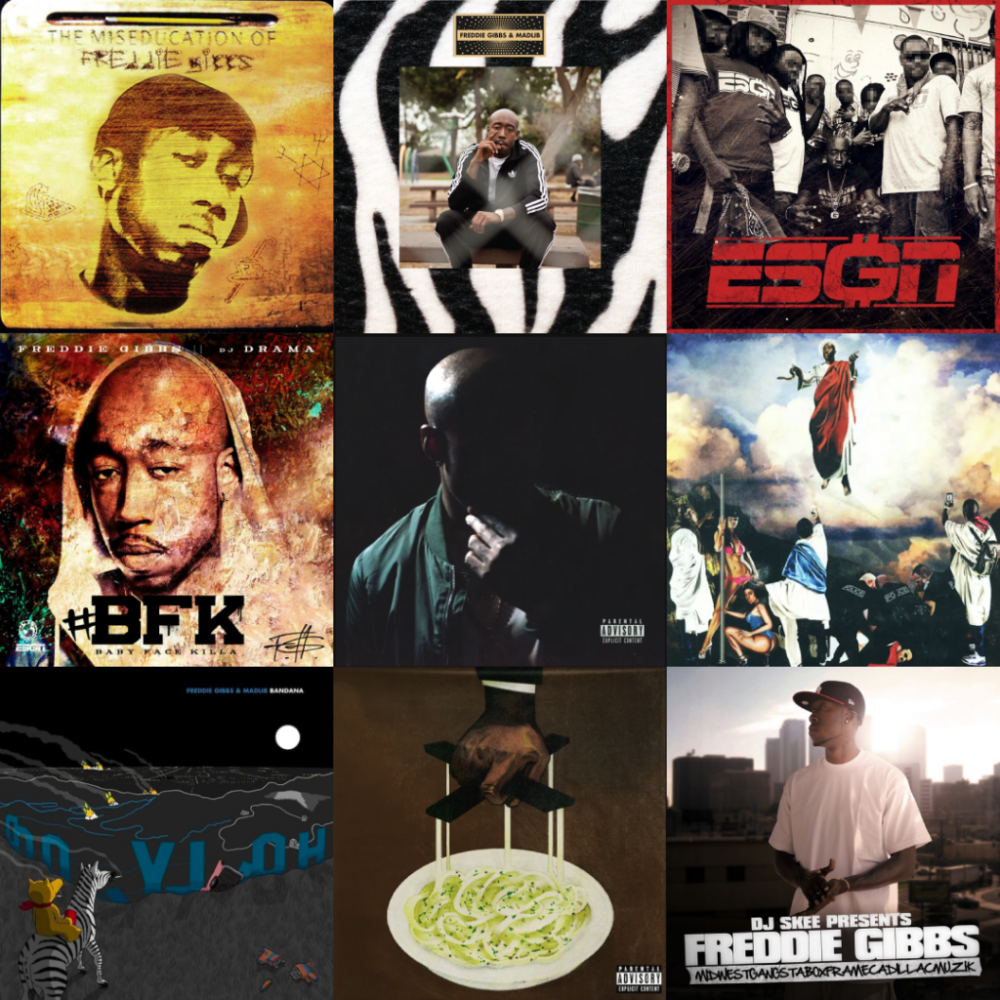

More than 15 projects into his career, Gibbs has a body of work that could go up against anybody. In this article, Gibbs is going up against himself. There are omissions. Namely, a few EPs with music that resurfaced later, like the Madlib collabs, and Fuckin’ With Fred, the 2011 DJ Roc mixtape I never listened to. Str8 Slammin’ editions 1-3 are also excluded but you might as well consider them last. Don’t ask why. The order might not be right but it is definitive. Please keep arguments in the comment section uncivil.

14. Lord Giveth, Lord Taketh Away (2011)

The most important career move Gibbs ever made was choosing to collaborate with a lone producer for an entire project. When stacked up against the rest of Gibbs’ discography, Lord Giveth, Lord Taketh Away laid the foundation for his future work with Madlib and The Alchemist.

Working with the producer over the course of a single day session—which according to the Microsoft Paint masterpiece of an album cover, took place in a studio replenished with plenty of Beck’s and Smartwater—gave Gibbs a cultural cache. Unfortunately, as upcoming blurbs will explore further, the sort of cache Gibbs was seeking in this era—under the tutelage of Jeezy’s CTE label—did not accentuate the best aspects of his musicality.

A Statik Selektah collaboration in 2011 meant a co-sign from a respected beatmaker and DJ who had a firm grasp on fundamentals. An of-that-moment producer with a recognizable tag, who harkened back to a better time one vinyl scratch at a time. When Gibbs should have been focusing on refining his voice, and ducking the traditionalist labels that dogged him, he was still trying to conform to a contemporary sound that was already becoming outdated. On Lord Giveth, Lord Taketh Away, he’s pulling in two directions: toward the conventions of the past and also the sounds of the then-present. The result, like much of his work in the CTE era, is suspended in that ill-fated middle ground: much farther than it should be from the true Gibbs voice that would come to define him.

13. Cold Day in Hell (2011)

In retrospect, the first mixtape Gibbs released after linking with Jeezy’s CTE label should have been a warning sign that that particular business relationship would not prove beneficial to his creative direction. By late 2011, Jeezy’s solo appeal was waning. Crooned R&B hooks and rolling snare fills with cranking sweeps were the norm—demanded and expected even—but big shiny pop-trap was fading out with a sad whimper, like the stab of a Scott Storch synth horn.

If the criticisms of Gibbs in his early career were that he was too one-note, Cold Day in Hell is too wrong-note. It might be a simple matter of engineering: the beats are blown out and Gibbs’ vocals aren’t properly mixed. This project has never been a pleasant listen for the ears, even if my 2011 ears listened to it incessantly.

Sound quality aside, the production choices include the J.U.S.T.I.C.E. League but evoke J.U.S.T.I.C.E. League karaoke: “type beat” mp3s downloaded from whatever the BeatStars predecessor was back then. As great as Rick Ross is on Alfredo’s “Scottie Beam” and Soul Sold Separately’s “Lobster Omelette,” and as much as both rappers have shown that they can slot themselves into multiple production styles, Gibbs’ best attributes are not accentuated by these sorts of beats. He shouldn’t be going in over tracks from the Teflon Don cutting room floor. Whereas Jeezy’s slower delivery works better over this production style—distorted drums and thin horns opening plenty of space for yelling out extended scratchy adlibs—Gibbs’ flow deserves more than the cheap and bombastic.

Gibbs can rap over anything, but he didn’t belong to this moment of musical time. He represented the resistance to this time. He was always underground but not, to many ears, underground enough. Gibbs didn’t become mainstream then, because his attempts to match the popular sounds of this particular era never made sense. Connecting with CTE was a learning experience that could have, but didn’t, shake him out of his throwback sensibilities. He had to go through Cold Day in Hell in order to know what didn’t work, to shake off those tendencies himself, and move forward in his own direction.

12. Fetti (2018)

Many fans derive the same sort of pleasure from Curren$y’s discography as I do Freddie Gibbs’. Spitta’s back catalog is far more extensive. Across every project, he too, shows how he can rap bar-for-bar with the best. It is almost boring how consistently good he is.

Produced entirely by The Alchemist, Fetti is the Alfredo predecessor. It came out a few months after Freddie, and was a tonal shift in the opposite direction. A sharp pumping on the breaks from that album’s aggressive energy. A relaxation.

It went too far. The pace is too slow. Fetti is as reliable as any record featuring these three should be. It is, like Curren$y’s consistent excellence, almost boring. On Alfredo, The Alchemist would find samples and drums better suited for Gibbs’ energy level. Push him up, in tempo or energy, rather than lure him down. The saving grace is that no one in this trio could possibly drag a project too low. In contrast to the frenzy of Freddie that preceded it, it was also nice to hear Gibbs ease up a bit.

This project never connected with me, but I can understand how and why it connected with others. Calling it almost boring is almost insulting. How could it really be boring when it laid the foundation for such a small yet significant thing: Alchemist and Gibbs enjoying working together.

11. Freddie (2018)

With the exception of Soul Sold Separately’s stand-up comedian call-in interludes—which showcase how Gibbs the person appeals to supposedly funny individuals, but doesn’t display his own natural ability for humorous storytelling or wisecracking—Gibbs has kept his lighthearted off-mic persona separate from the more serious, more sinister MC he embodies on records. This album cover’s Teddy Pendergrass allusion suggested that Gibbs had fully embraced his humorous side on Freddie, or had found it again after the nightmare he experienced in Europe. Instead, Freddie is harder and grimier. The exception is “FLFM (Interlude),” a rendition of “If You” twisted with sophomoric lyrics, like Freddie did later to “Waterfalls” on Piñata’s “Robes. It’s funny on the first listen but then just grating.

The beats on Freddie—the majority of which come from Kenny Beats, and one from now-WiFiGawd collaborator Tony Seltzer—are sparser. They place less emphasis on melody, and a bigger emphasis on deep hitting kicks, loud popping snares, and the complex arrangement of drum patterns. In tight rhythm as usual, Freddie raps like he has something to prove, again. If you prove something enough, like Gibbs does with his rap skill, how often do you have to keep proving it? When is enough enough?

Freddie had no option but to prove himself again on Freddie. By the time this album came out in summer 2018, Gibbs had been home for a while. You Only Live 2wice, his initial redemption piece, had been out for a year. He was acquitted. He was home. Now he could exercise his newfound freedom, celebrating on the beat.

It wasn’t easy for Freddie to reintegrate into a society which, in large part, distanced themselves as the case played out. Sexual abuse charges, even for the accused innocent, are difficult to recover from. As much as Gibbs revealed glimpses of his personality and family life via social media, none of his fans could claim to know the real him. You Only Live 2wice had him dusting off the cobwebs. Freddie was his official reintroduction, with bigger stakes. It wasn’t easy to buy back in. The Me Too movement had swept the world in the lead up to the album’s release, and the full extent of what actually occurred in Austria wasn’t entirely clear to those who weren’t paying close attention.

Gibbs’ lyrics had been used against him in Austrian court. Here, he graciously embraces the First Amendment, returning with unabashedly sexually suggestive lyrics (more so than on previous projects, and also more noticeable). Perhaps I’m a prude or a faux woke snowflake, but when Freddie came out it was difficult to digest. I wanted to hear something more introspective from him, even though now I understand that that wouldn’t have made any sense. The standout was “Death Row,” which had an 03 Greedo feature in the year the Wolf of Grape Street stared down his 20 year sentence, over a Kenny Beats “Boyz N The Hood” flip. That one still goes.

Over time, Freddie has proven to be one of the more sonically cohesive projects in Gibbs’ repertoire, with a trimmed-down tracklist that gives it an advantage over more meandering works. My misguided perception of Freddie back then may be misleading my low ranking of Freddie now. But the album still lacks something crucial. The production is too empty, and Gibbs’ lyrics don’t do enough to fill it. This project was a needed link between a low period of Gibbs’ life and the resurgence that would follow. If this is the direction he needed to take to get back on the right path, so be it.

10. ESGN (2013)

Like Freddie, ESGN forced Gibbs to reaffirm himself. In this instance, he was returning to independence after his brief run with CTE. He had to come back like this: an album featuring members of the Gary posse like Hit Screwface and G-Fleezy, the brand and the homies firmly asserted on the album imagery. He woke up, got his smoke up, put his dope up and said fuck the world. Fuck everybody besides those that have been riding with him all along. Fuck everything besides ESGN.

By 2013, Gibbs had allowed the Southern California sunshine to seep into his skin. It didn’t wipe away the clouds of his Gary past, but his music did slot in alongside the L.A. gangster rap that raised him from a distance before his migration. Lil’ Sodi does the intro. Daz Dillinger, Spice-1, Problem, and Jay Rock all provide guest verses.

Coming out a couple of years after Cold Day in Hell, ESGN is more polished and better-produced than its counterpart but follows a similar sonic playbook. Despite distancing himself from Jeezy, ESGN aligns with the grittier underbelly of the pop-trap of this era. The first eight tracks are certified classics, but the tape sprawls on for over an hour.

At a time when hip-hop fandom still consisted of obsessively downloading free mixtapes and organizing them into iTunes files, this much Gibbs music was very much welcome. Billed at the time as his “debut studio LP,” ESGN did not live up to its potential. It’s too scattered. Too much filler. Considering the amount of songs that do stand the test of time, it’s also an example of how Gibbs can transform even the most middling beat into a solid 3-min-plus track with an irresistible hook.

After ESGN, before his arrest in Europe, Gibbs would continue refining a sound that further distanced himself from the Jeezy associations, and more accurately represented the peak of his unique skill set. ESGN is the proof-of-concept that Gibbs can be more than a one-note mixtape artist, and that he’s better off alone than working with a label attempting to herd his freewheeling ideas in a particular direction. If it’s ESGN or die, the answer will always be the former.

9. You Only Live 2wice (2017)

Before he could get to Freddie, Gibbs had to release this redemptive effort. Although my memory of the respective album rollouts places Freddie as more of an official album and this as a shorter EP, the runtime of You Only Live 2wice is six minutes longer. The quality of the songwriting—influenced in part by Gibbs’ renewed sense of clarity, and appreciation for the smaller things-is at least six times stronger.

Delivered to the world a year after The Life of Pablo, You Only Live 2wice accomplished a similar feat as Kanye. When everyone was expecting Gibbs to falter, to come back changed in the wrong way to a fanbase who might have wanted to forget about him, he reaffirmed his relevance. On “Alexys,” one of his most underrated cuts ever, he gives another nod to Scarface and describes himself as the baby version, manifesting the dream collaboration that would surface on Piñata and later Soul Sold Separately. “Crushed Glass” is close behind.

Since this was the first project Gibbs put out after his return from Europe, the light thematic throughline is a redemption tale of not-quite-Kanye-esque religious proportions. On the cover he floats in heaven, decked out in flowing robes. Beneath him are strippers, brutalizing cops, and a guy snapping a photo. The intro features Jesus.

After spending more than a month in a foreign prison, staring down a sentencing of 10 years, and waiting around for several more months in a country whose media portrayed him as a big, bad, Black American Villain, a panel of German-speaking judges acquitted Gibbs on all charges. You Only Live 2wice is cognizant of his experience, and alludes to the incident more directly than Freddie would, but it also picks right back up where Shadow of a Doubt left off in terms of the honed-in sound he’d begun establishing before he went away. If the Europe thing hadn’t happened, the shakiness of the return might not be detectable. But Gibbs beat his case because he fought it, refusing to take a plea deal for a crime he did not commit. Despite the project’s imperfections, he came back strong with You Only Live 2wice, because returning to his most honest form was his only feasible option.

8. Bandana (2019)

The expectations of a Piñata follow-up were never attainable. The magic couldn’t be recreated because the novelty had worn out. Bandana succeeded because of how effortless it was for them to run back 15 tracks. Madlib infamously claimed he produced the beats on an iPad, sending his worshippers scrambling to sell their SP-404s on Reverb. How did he make “Crime Pays” on a touch screen? How did Gibbs destroy that one, and 14 others, yet again?

When sharing my definitive rankings with a few other Gibbs fans, the biggest feedback I got is that Bandana is too low. Don’t I know that it charted higher than Piñata? Listening back, I’m probably underrating it. “Practice” is far better in reality than it is in my memory. Maybe it’s because it came out in 2019 and my capacity for music enjoyment blacked out not long after that. As I’ll get into more in the Piñata blurb, I’ve also never loved Gibbs over Madlib production, even if I prefer Madlib production over almost any other beatmaker in Gibbs’ history. I don’t claim to be logical. That’s just how I feel.

More so than Piñata, Bandana operates on instinctive feeling. Unconcerned with the impossible expectations of making another classic, both Gibbs and Madlib were free to be looser, to show out more. It makes sense that Quasimoto appears on the album artwork, sitting on a zebra watching his pink car crashing through the Hollywood Sign, Los Angeles burning in the background. The piñata in the bottom right corner is symbolically busted.

Bandana is another project from two artists who excel at their crafts with minimal effort, whose styles at first glance seem antithetical but whose independent mindsets and respect for their musical forefathers binds them across space and time. The ease with which they were able to pump this out, even if it took a few years since the last one, at first seemed like a detriment. Now I recognize that’s what makes it genius. I’m still going to leave it at #8 but if I spend a little more time with it it’ll probably move up.

7. Baby Face Killa (2012)

On Baby Face Killa, deep into the race, when nobody expected it, Gibbs lapped everybody. Despite reverting back to the Gary emphasis on ESGN, at this point Gibbs’ was leaning less on his origin story and developing more into a complete artist with an evolved perspective. Positioning himself as the standalone star he would soon become.

Not everything in the CTE era was bad. Released during his brief year-and-a-half tenure on Jeezy’s label, and featuring his boss on “Go For It,” Baby Face Killa plays like an attempt at making his street energy into a more palpable form for the mainstream. The Gary allusions are tapered back and subtler; on “Still Livin” he’s “moonwalking on dope.” “Boxframe Cadillac” is repurposed from the riding-around-the-city anthem it was on Midwestboxframecadillacmuzik to a failed attempt at a hit with a smoothly sung hook.

Whereas his earliest mixtapes contained tracks originally intended for major label distribution, Baby Face Killa feels like a proper mixtape in the lead up to an eventual album. Again, that album never came. The songs on this tape are not as polished as they could be, and listening to it evokes the uncanny valley: Freddie Gibbs is not Young Jeezy, but he’s good enough that he could be. “Bout It Bout It” is a genuine banger, perhaps the only song on Kirko Bangz’s nonexistent Greatest Hits album. Krayzie Bone on “Kush Cloud” legitimizes and provides a direct connection to a throughline of Gibbs’ work: including at least one track on every album that’s inspired by Bone Thugs (and/or Twista and/or Do or Die).

Baby Face Killa represents a transitional point in Gibbs’ discography. The curve of the race track, if you will. A tape that is not an album, but showed what an album could be. Time will tell if this holds true, but Soul Sold Separately is in a weird way reminiscent of Baby Face Killa. An attempt at a bigger budget splash of an album, that might not be what it intends, but does offer enough flashes of brilliance to place it above artists who spend much more energy and money on attempting the same.

6. The Miseducation of Freddie Gibbs (2009)

After a series of 10 mixtapes, self-released between 2004 and 2009, Freddie Gibbs’ music career began in earnest with this seminal mixtape. The Miseducation of Freddie Gibbs came at the tail end of the Weezy-led mixtape era, and jump-started Gibbs’ independent streak, but many of its songs formed while he was a major label artist.

In 2006, Gibbs signed with Interscope, left Gary and moved to L.A. By 2007—after the exec who signed him, Joe Weinberger, left the label—Interscope dropped Gibbs before his debut album came out. This brief stint with the bureaucracy and red tape of the official music industry prepared Gibbs for what would come later with CTE, and would emphasize the importance of dictating control over one’s own career path.

In an interview with Pitchfork, Gibbs mentioned that “about 60%” of the songs on this tape came from Interscope recording sessions. As a major label signee, Gibbs met producers like Just Blaze and The Alchemist, relationships that would resurface at crucial moments later in his career. Rapping over new production from established beatmakers also differentiated Gibbs from the outpouring of mixtapes from lesser MCs recycling the same underlying songs around this era. The Miseducation of Freddie Gibbs was not an official debut, but the potential for what such a debut might sound like.

The tape showed that a lyrical MC from Gary, Indiana could weave street tales that resonate with wider audiences. It opens with “GI Pride,” a song that exposes the predominant sounds of the era – like Jeezy with triumphant synth strings, and an over-the-top, dramatic backing beat. “GI Pride” is a necessary explanation of where Gibbs came from: the overlooked city across the border from Chicago where poverty and sadness reigns but Kings of Pop sometimes rise up out of the trash heap (which Gibbs literally raps in front of in the video for “What It Be Like”). For audiences who weren’t prepared to focus on non-coastal geography, he makes sure his origins are well understood: This is Gangsta Gibbs from the G. He may have fled West like MJ, but he is not going anywhere.

By the time the aforementioned “What It B Like” video—a low budget clip shot in a few cold-seeming locations during a Gary winter—came out, Gibbs’ crew was already decked out in “G” merch. Interscope be damned, the independent hustle was moving forward in full force. The end of that song finds Gibbs shouting out multiple sets before concluding, “we’re all the same gang.” Back then, before embracing the Vice Lord imagery of Soul Sold Separately, his social media presence and the rabbit furry that dances around at his shows, Gibbs was a rare gangsta rapper who prioritized lyrical ability over specific loyalty. In the process he established his brand: Freddie Gibbs.

This album caught on with outlets like this here POW, which published post after post declaring Gibbs’ greatness, and XXL, who named him a 2010 Freshman, and Pitchfork, which gave The Miseducation of Freddie Gibbs a 7.8. Gibbs performed at the Pitchfork Music Festival the next year. Although the subject matter of this particular project is straightforward and serious, his charisma and humor began to seep through during live performances and behind-the-scenes clips.

With this tape in heavy rotation, my friends and I loved referencing a now-deleted YouTube video from backstage at Pitchfork, where Gibbs and Best Coast talked about their smoking habits. Gibbs laughs at Best Coast, amazed she only smokes an eighth per week. When asked how much he smokes, Gibbs answers immediately: “21 blunts a day. If I smoke 30, oops!” [ed. note: can confirm this was true] The Miseducation of Freddie Gibbs laid the foundation for a multi-faceted superstar. Before we latched onto his magnetic personality, he drew us in with an objective display of raw skill.

5. Midwestgangstacadillacboxframecadillacmuzik (2009)

Released a few months after The Miseducation of Freddie Gibbs, Midwestgangstacadillacboxframecadillacmuzik proved that not only was his breakthrough mixtape not a fluke, but that he could do the same thing again and again, with a slightly different tone and approach, without sacrificing the quality of his established technical vitality.

Like its predecessor, this tape opens with a statement song. It’s self-explanatory. There is no one else in his category. He fashioned his sound after his heroes, but his background and approach separate him from everybody.

As the title suggests, Midwestgangstacadillacboxframecadillacmuzik is imbued with Southern influence, from the chopped N screwed hooks on “Boxframe Cadillac” and others to the Pill verse on “Womb 2 The Tomb.” He reiterates that he’s from Gary, and his outlook is indebted to the Midwest, but on this tape he began morphing his music into a regionally agnostic sound. He interpolates Eminem’s “Superman” on the hook of the Devin the Dude-featuring “Sumthin U Should Know.” Invokes Biggie’s “What’s Beef” on “Still Standing.” Flows with the consistency of Big Boi and pushes his vocals like Andre 3000, asserting once again that Gary has got something to say.

Depending on the mood, the number 5 spot is a toss up between this one and The Miseducation of Freddie Gibbs. In most instances, Midwestgangstacadillacboxframecadillacmuzik wins out.

4. Piñata (2014)

Any demographic resisting Gibbs fandom joined the cult when Piñata came out. Few MCs can rap over one Madlib beat. Fewer still can make sense of the producer’s madness, transforming a loose collection of atypical beats into a cohesive project. Piñata was an instant classic to a certain subset of music fans, and the album’s reception justly granted Gibbs the legendary status he long deserved.

What might not have been evident to that resisting subset prior was that Gibbs doesn’t need traditional song structure. He can rap over anything, and he actually raps. Unlike his peers, he can actually rap live, and has done so during concerts with a real backing band. When presented with Madlib’s beats, which are often laid down and mixed with the amorphous form of free jazz experimentalism, Gibbs both rides the beat’s waves and conducts them like the gravitational pull of the moon. He is capable of rapping front to back like Madlib’s best collaborators have done. He also figured out how to make hooks—like on “Thuggin’” or the mild sauce anthem “Harold’s”—fit in where they can.

Madlib infamously tends not to work with artists in the studio so it was never a secret that Gibbs was working with what he was given, applying a coat of Gangster Gibbs steady flow to Madlib’s avante-garde brushstrokes. Many of these beats were on the hundred-song beat tapes Madlib put together and Stones Throw shipped out to potential MCs in the early 2000s. Some of them are beats that DOOM eschewed during the selection process for Madvillainy.

Gibbs references Madlib’s decisions, like playing off the sample for the thematic construction of “Deeper,” but he makes the songs wholly his own. A street tale like “Knicks” is more refined than on Gibbs’ earlier work. The themes of drug dealing are laid out on “Supplier” and as consistent throughout the remaining tracklist as Gibbs’ flow (despite dropping “Cocaine” from the original title). The list of featured artists was an instantaneous wet dream for underground hip-hop fans in 2014. For Gibbs too: the Scarface feature on “Broken” was on par with the certification of Krayzie Bone on Baby Face Killa, in terms of collaborating with influences. But deeper.

Piñata is demonstrative proof of Gibbs’ talent, but it’s not a necessary demonstration. Without knocking Madlib’s indisputable prowess, there are other producers who are more capable of drawing out Gibbs’ best. SPOILER ALERT: my #3 pick on this list might insinuate that I mean The Alchemist is that producer, but that’s not the case either. In fact, when The Alchemist was the surprise last-minute replacement for Madlib at Gibbs’ show at The Novo earlier this year, it was one of the most disappointing moments of my life. On Piñata, Gibbs showed that he can handle Madlib beats because he can handle anything. For those who didn’t already know that, this was the evidence.

3. Alfredo (2021)

A distinguished collaboration with The Alchemist, Alfredo is both the most obvious and least logical pick for Freddie Gibbs’ best album. Two artists who enjoyed working together so much they dropped the third member of their unofficial trio, and made it to the Grammys. Alfredo presents the collaborative product of their respective decades-long underground grind. This album was made for a populace finally primed to accept them as mainstream stars. But a musician’s best work is not supposed to arrive this many projects into their career, especially not on an LP that opens with a guitar solo.

Alfredo landis at #3 for reasons that aren’t objective, but it’s worth noting that this was, until the last second, my #1 pick. I will continue to describe it as his “best album” because that term is inherently meaningless when you really think about it, but when you really think about it, this might be his best album. It’s been over a year so this is not recency bias.

More concise than Piñata, more cohesive than Shadow of a Doubt, Alfredo might be Gibbs’ only actual project that is straight killer, no filler. “Baby $hit” is the greatest diaper-changing ode to hustler-minded fatherhood since Tim Heidecker’s “Cleaning Up The Dog Shit.” “Scottie Beam” lets Gibbs’ voice be a militant rhythm section, like each syllable is the rattle of a stick against a snare, and Rick Ross’s feature is the perfectly-timed cymbal crash. “Look At Me” is perfect, “God Is Perfect” is almost. Do you want me to go through every song?

The collaboration with the Grammy winner—Tyler, The Creator, on “Something to Rap About”—should win some sort of actually meaningful award. Tyler’s verse is exquisite in its vivid imagery. Gibbs claims on the song that he’s bringing out his old self, but Alfredo is just another repositioning of Gibbs’ same self in front of a different backdrop. Or, rather, in front of a comparable backdrop to Fetti, but with more complete songs.

As Gibbs’ career goes on, we will learn which projects have lasting value. Is it the collaborative efforts like Alfredo, Piñata, or the Statik Selektah one? Or is it the big budget bonanzas like Soul Sold Separately? My chips are all in on Alfredo.

2. Str8 Killa No Filla (2010)

What else is there to say about Gibbs’ post-Interscope, pre-CTE mixtape run? Perhaps just a reminder that this period is when the relatable quirks of his infectious personality were starting to seep through, slipping past a lyrical output devoid of levity or humor. Whatever social media platforms were predominant in 2010, Gibbs was on them cracking jokes, posting memes, being honest, Be(ing)Real. Like a reality star, his personal life began to unveil itself in bits and pieces. His uncle Big Time Watts was one of many characters in the extended universe of his ongoing real time sitcom. The music he put out was a darker, more serious tonal contrast that made total sense because it was as honest as his on-camera or on-Twitter personality. Str8 Killa No Filla came out after The Miseducation of Freddie Gibbs and Midwestboxframecadillacmuzik had had time to marinate. A fuller picture of the man behind the music began to take form.

It’s unsurprising to learn, with hindsight, that Speakerbomb had a hand in creating “National Anthem (Fuck the World),” the number one soundtrack for my friends and I during a formative period of our lives. This happens to be the same 2010 period in which I went to a GZA show at The Echoplex like many like-minded strangers specifically to see Freddie Gibbs, but had to sit through an opening set from some guy named Kendrick Lamar first. When Jay Rock came onstage to perform “Rep 2 Tha Fullest,” my brain actually invented the mind-blown emoji. The placement of Str8 Killa No Filla at #2 undeniably benefits from a nostalgia bump. Longtime fans may disagree. I don’t care. As Gibbs says on track twelve: “This right here is personal.”

1. Shadow of a Doubt (2015)

Madlib was the key that unlocked Gibbs’ key-flipping tales for the masses, but Speakerbomb is the locksmith with an ear tailor-made for Freddie like his monochrome Adidas tracksuits. Aside from Mike Dean’s solo credit on the closing song, ESGN’s in-house engineer touched every track on Shadow of a Doubt: the album with production that best fits Freddie’s specific style. The only proper reaction to a song as strong as “Fuckin’ Up The Count” is a re-enactment of that scene from The Wire where they say shit a lot. Shitting on any beat, it can not be overstated enough, is what Gibbs does best. The beats don’t spurt back up at him better than they do on this album. With Boi-1da, 808 Mafia, Kaytranada and others getting the process started, Speakerbomb didn’t do all the heavy lifting. But his presence left a tangible impression on the finished product. His finessing made Gibbs sound, finally, exactly like himself.

The first two noteworthy mixtapes found Freddie honoring his roots while testing the edges of what a rapper with his background and from his city could sound like, experimenting to a limited point. On Shadow of a Doubt, he included a clip of Snoop Dogg outright telling him he invented the Gary sound, but the album overall was a progressive leap forward. The tone acknowledged Gibbs’ past, and the lyricism replicated the drug dealing tropes that brought him to this point, but the autotune croon of “Basketball Wives” and the layered singing on “Lately” were not the standard Bone Thugs/Do or Die cuts fans had grown accustomed to expect. Songs like these emphasized the lesser-celebrated attributes of Gibbs’ craft. He was always ready to rap on any beat, but on Shadow of a Doubt he developed into a songwriter more comfortable with exploring the limits of his own range. He settled into his own lane, happy there at last but thankfully not content to continue on unchanged.

Small but eccentric choices imbue Shadow of a Doubt with lasting listening power. Don’t you remember the drums dropping out for Black Thought’s second verse on “Extradite”? Can’t you recall then-incarcerated Gucci Mane’s tiny contribution to “10 Times”? Didn’t “Mexico” kind of sound like Ace Hood’s “Bugatti”? Who can ever forget ManMan Savage? How did I forget to mention E-40?

On my initial construction of this list, the length and relative lack of cohesion of Shadow of a Doubt disqualified it from top honors. The more I listened back, and the more I wrote, I came to realize that this is the best. Ranking Alfredo at #1, as I originally conceived it, must have been recency bias. Even if putting Str8 Killa No Filla and Shadow of a Doubt right here at the top is, again, personal.

The promotional event for Shadow of a Doubt coincided with a free giveaway of Gibbs’ cannabis strain, a lowkey affair at Los Globos that contrasts with the high-stakes, high-profile two-day first come first served Soul Sold Separately listening party at Hollywood’s Dolby Theater. Eternal man of the people, Gibbs spent hours chain smoking blunts in a circle of iPhone 6s Plus-flashing fans. He reportedly did at some point take the stage to drunkenly recite the album’s lyrics into a microphone for the few fans not too stoned to stick around. As I wrote in my review of the album when it came out, the positive energy of that night, coupled with the strength of the project, confirmed that he had moved well beyond the hindrances of Interscope and CTE, and ESGN’s independent brand had been firmly established. On charisma alone, Freddie Gibbs the brand was born.

The narrative did play out as I anticipated, but not in a linear direction. Shadow of a Doubt was the last we heard from Freddie before the forced silence of his year and a half dealing with what happened in Europe. Seven years after this album’s release, Freddie Gibbs the brand has once again ascended to imaginable yet seemingly insurmountable heights.

In retrospect, Shadow of a Doubt feels like another misdirection, another (mis)representation of a Freddie that could have been. The tone shifted again on You Only Live 2wice and Freddie, and never made its way back to where he left off here. The direction Gibbs took Shadow of a Doubt, like so many other ventures in his career, didn’t turn out to be his final form. For an artist who evolves incessantly, Shadow of the Doubt is the purest emblem of his truest self, flaws and all.