Donate to the Patreon. Support independent media or else it won’t exist.

Jeff Weiss believes that it’s a bad time for the empire.

A wise man once told me that those who really like Wu-Tang think Raekwon’s Only Built 4 Cuban Linx is the greatest solo album the Clan ever released, but those who understand Wu-Tang prefer Liquid Swords. Naturally, this is highly subjective. Under any rubric, they’re both pretty perfect records. It’s generally impossible to find flaws in the Wu-Tang Clan’s run from ’93 to ’96.

Enter the Wu-Tang and the first five solo records featuring nine rappers gunning against the world, decapitating a soundtrack of creaky soul songs sinisterly repurposed by the RZA. They divined an ecclesiastical canon that sounded best heard through a hotboxed Jeep. These albums are now accepted Gospels, but even among them, the GZA’s Liquid Swords stands apart as a gnostic document of more ancient testament.

Liquid Swords is the purest distillation of Wu mythology, a prequel to Enter the Wu-Tang. It’s the story of the Clan’s Exodus-like wanderings through the burnt-out patches of all five boroughs during the crack-ravaged Reagan years, each verse sketching a whirling world of internecine warfare and decaying, poverty-infested projects. Released in the winter of 1995, the RZA declared that his intent was to make people shiver in their cars, and when you listen to Liquid Swords, its permafrost production still batters like gusts of spine-stiffening wind crashing into sheets of freezing rain.

From the first lisped clips of dialogue lifted from the Japanese samurai flick The Shogun Assassin, the record shuttles back and forth between parallel universes, with the GZA’s vivid sketches of hell alternating with cinematic tales of empires run by paranoid, shuttered-in shoguns with brains infected by devils and a blood lust for decapitation.

But the recurring motif only emerged in the last days of recording:

“We didn’t even have a theme until it came down to the day of mastering and then one of the last days we were mastering it, RZA asked someone in the studio to go out and get the Shogun’s Assassin,” GZA said. “It wasn’t like we came in with that plan from the onset. Imagine what the album might’ve been like without that, would it have been as good, what could’ve replaced it? I’m not sure, that’s just the way it unfolded.”

Nonetheless, the tone is seamless: all horror, a living, breathing nightmare animated in murky newspaper grays with a blood-red tint. Whereas Enter the Wu-Tang had its inherent limitations in that RZA was forced to split the playing time among all nine Clansmen, Liquid Swords stands as a perfect crystallization of the Clan’s weird, wise alchemy of kung fu, Five Percenter slang, comics, chess and criminology raps.

“It’s the balance that attracts me to it. It’s almost like getting an advanced degree,” GZA said, about the album’s 5 Percent origins. “It’s a science to observe it, to define, it’s like having knowledge, you understand life better. The more knowledge you have, the more you understand life. That was the whole science behind when Ghost would be talking about ‘Why is the sky blue, Why is water wet.”

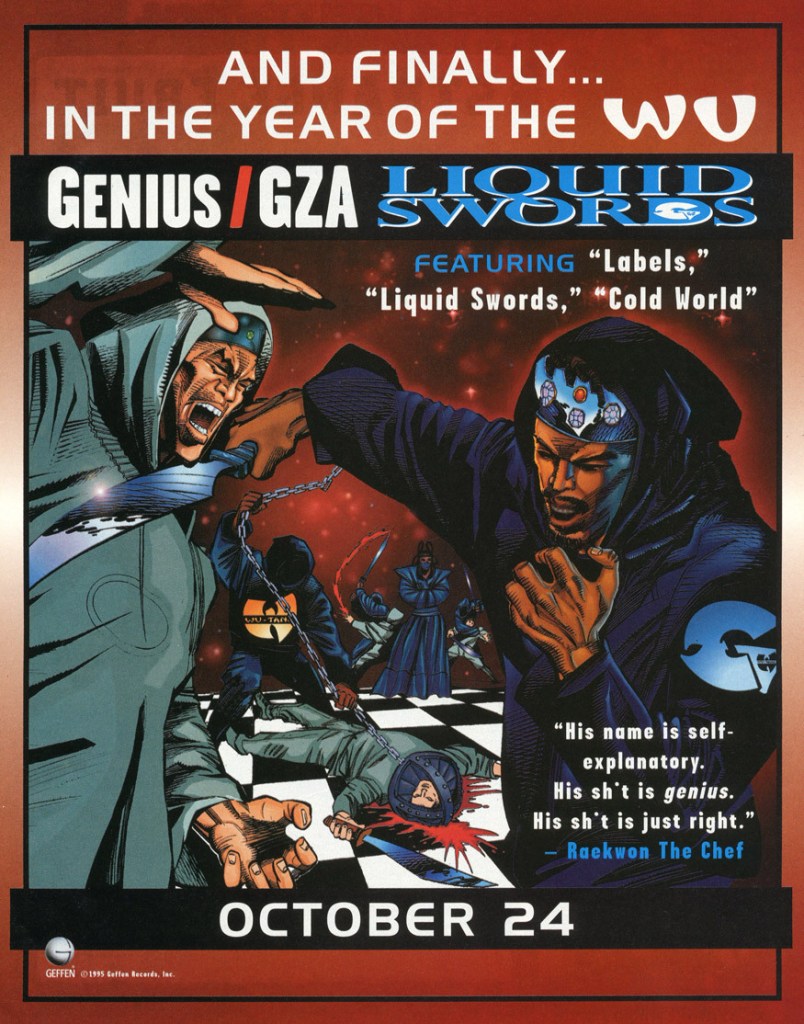

Obsessive in the execution of his vision, the GZA tapped famed DC Comics artist Denys Cowan to hand-draw the album cover — cloaked ninjas in Wu insignias slaughtering people across a chessboard — and Cowan directed and co-wrote each of the album’s four indelible videos.

Like all early Wu solo records, Liquid Swords features numerous and notable Clan guest appearances, but only on the Genius’ do they contort themselves to fit one singular cosmology. Ghostface Killah’s and RZA’s appearances on “4th Chamber” rank among their finest ever, with Ghost’s alter ego Starks in poison-tongued, corner-existentialist mode, mocking his competition for drinking apple Boone’s, dealing “white shit like blacks rock ashy legs,” before tilting his head to the heavens and posing atavistic, poignant questions.

But for all its originality, Liquid Swords represented a total synthesis of the influences that characterized the basis instructions of GZA’s first 29 years on earth.

“Take a song off Liquid Swords like “Swordsman,” [raps] “when a motherfucker steps out of place and gets slapped in his motherfuckin’ face.” That routine came off an Earth Wind and Fire hook and we revised it, and that’s where it came from,” GZA explained his strategy. “Things ain’t comin fast enough, there is no mountain high enough?” That comes from a Diana Ross and The Supremes, “Ain’t No Mountain.” I just took it and flipped it and made it on some street shit. It’s effortless, it’s just reviving it, and doing you, and being comfortable.”

Meanwhile, the RZA gave birth to his Bobby Digital alter ego, spending 16 bars describing the most gnarled dystopia he can imagine: traitors to the cause getting tossed into scalding lakes; government-ordered ninjas kidnapping your wife and children; and the state of humanity boiled down to its most basic. Method Man never sounded smoother or meaner than on “Shadowboxin’,” boasting about crunching “n**z like a Nestlé” while floating ethereally above the fray, like the song’s title, a commotion of shadow and light.

But the star of the show was the Genius himself. Gone was the Afrocentric-minded rapper enthralled with Big Daddy Kane who had made 1991’s Words From the Genius. In his stead was a darker, more complex artist, one channeling his fury at getting dropped by the Cold Chillin’ label into the vicious anti-industry screed, “Labels.”

On “I Gotcha Back,” he flashes back to his childhood and how he could’ve written a book with the title Age 12 and Going to Hell. On “Hell’s Wind Staff/Killah Hills 10304,” the GZA envisions himself as the notorious mob figure Grey Ghost, complete with intricate drug and jewel deals and Afghan henchmen putting bombs in bottles of champagne. Few rappers have ever delivered a more complete performance, with the GZA’s authoritative baritone and masterful economy of words lending themselves ideally to his role as omniscient narrator. His stories are compact and filled with crisp, complex rhymes that move with the steady, deliberate nature of the veteran chess player that he was.

“Chess is life in itself. It’s about planning, if you look at chess, it’s about question and answers,” GZA says. Your opponent moves first and it raises a question. You have to answer, sometimes you have the answer and sometimes you don’t.”

Several decades later, GZA can still pack shows across the globe merely by tossing “Presents Liquid Swords” in front of his name on the bill. Indeed, few albums have aged better than this masterpiece, a record that sounds as simultaneously ancient and modern as it was when it was first released. Ultimately, whether you prefer Liquid Swords, Only Built 4 Cuban Linx or any of the other great Wu records doesn’t matter much; what does is the fact that they’ve left — and are still leaving — a body of work imbued with timelessness.