Photos courtesy of Kansas City Police Department / Patrick Johnson

Donald Morrison read through thousands of pages of documents provided by the Kansas City Police Department to shed light on one of hip-hop’s biggest mysteries.

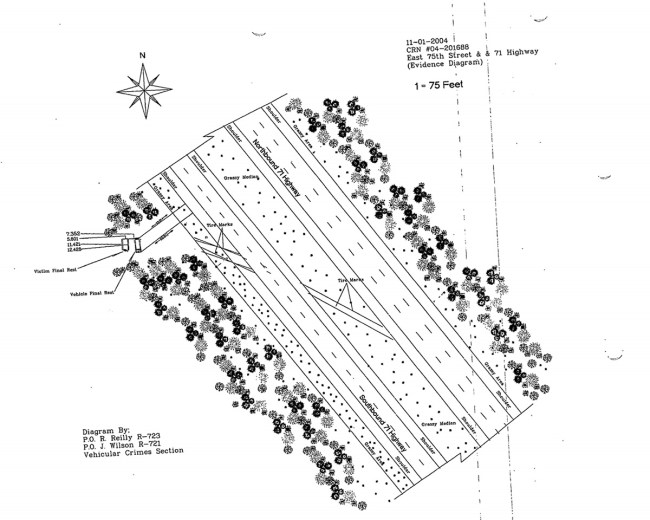

Kansas City Detective Everett Babcock arrived to the scene of a murder on the morning after Halloween in 2004. A totaled, white Dodge Legacy van was found on an embankment below Highway 71.

The area was poorly lit thanks to a series of street lights along the west edge of the highway. It appeared as if the van had spun sideways, slid around and went off the road, crashing into a muddy ditch.

The driver’s side of the van had been found with more than 30 bullet holes and a man was found shot to death nearby, having been thrown from the vehicle upon impact from the crash. It was an exceptionally violent scene.

“The victim was lying on his back, with his left leg out straight and his right leg bent at the knee,” Detective Babcock wrote in his crime scene report. This was several years before he would appear on America’s Most Wanted, American Gangster and a show on the Investigation Discovery channel about women who may have killed their husbands.

“The victim’s left arm was slightly across his body and his right arm was out straight,” he wrote. “The right side of the victim’s neck was up against a small tree.”

The white van allegedly belonged to Savino Davila, a 27-year-old man who prosecutors say was at the head of a drug trafficking organization that brought more than 330 pounds of cocaine into Kansas between 2000 and 2006.

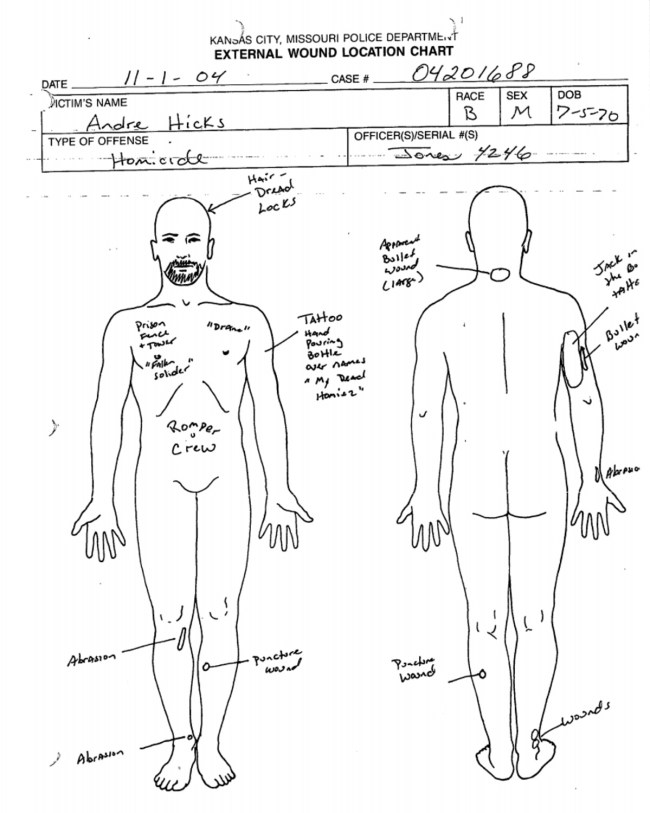

The dead body belonged to Andre Hicks, known to the world as Mac Dre, one of the most influential hip-hop artists in history.

Despite multiple investigations and a string of alleged retaliation murders that left three more people dead, very little is known about the actual circumstances surrounding the death of Mac Dre, Vallejo’s hometown hero, the larger than life orchestrator of the Thizzle Dance and a key player in the Hyphy movement that still influences hip-hop culture to this day.

The KCPD have never arrested or charged anybody with the murder and the high profile nature of the killing has continued to generate rumors and theories among hip-hop fans and true crime aficionados.

The complete story of how, why and who killed one of the greatest rappers of all time is laid out in more than 1,200 never before seen documents requested from the KCPD. Detectives spoke with dozens of witnesses and suspects over the years; they spent an untold amount of money and manpower to solve this case and yet they’ve never even released a suspect name. The KCPD has declined to comment on the documents.

However, in a brief phone interview from January 25, 2021, Detective Babcock said that the media department within the KCPD wouldn’t approve detectives to speak publicly about the case. He said they feared that the interview would only cause more problems for the people involved.

“I remember everything about that case,” Detective Babcock says. “I lived that case for I don’t know how many years.”

When asked if it was frustrating being unable to shut a case after all the work he’d done over more than a decade, Detective Babcock said this:

“I mean, you have the case files,” he says. “It’s not a mystery if you look at the case file.”

Life’s a Bitch (and then you die)

Photo via KCPD

There is a mural of Mac Dre in the Ivy Hill section of Oakland, California, the place where he was born on July 5, 1970. When he was three, he moved 30 minutes north to Vallejo, a city of just over 120,000, famous for having the first United States Navy base on the Pacific Coast.

From an early age, Mac Dre gravitated towards a section of Vallejo called the Country Club Crest, an out-of-the-way neighborhood long known to outsiders as a hotbed of drug crime and violence. But to some it meant much more.

Sleep Dank, a Vallejo rapper and friend of Mac Dre’s, was born and raised in the Country Club Crest. He remembers first meeting Mac Dre in 1986.

“When he [Mac Dre] came to The Crest for the first time, he just got addicted. His mom didn’t want him out there, but he didn’t want to go home,” Sleep Dank says. “Dre’ got jumped into The Crest. Motherfucker’s would try to beat him up because they were jealous of him. He went through a lot.”

Mac Dre’s name pays homage to another one of Vallejo’s musical legends, Michael “The Mac” Robinson, who was only able to release two EP’s under Strictly Business Records, before being shot to death in 1991.

Mac Dre’s final album, released only 13 days before his murder, was meant to be the spiritual successor of The Mac’s first EP from 1988, The Game is Thick. This monumental EP is the quintessential Bay Area deep cut; a springboard that launched the pimp archetype that artists like Mac Dre, Too $hort, Suga Free and E-40 would later expand on, and in some cases, perfect. Sleep Dank looked up to Mac Dre.

“Some people wanted to sell drugs, and do all that,” Sleep Dank says. “Dre was just straight music. He knew he was onto something so he stopped doing anything dirty. That’s a tip I took from him.”

Even if it’s a controversial statement outside of the Bay Area, Mac Dre belongs on top five greatest MC lists. His 1989 debut EP, Young Black Brotha, is foundational to West Coast hip-hop. It’s single, “Too Hard 4 the Fuckin’ Radio,” recorded while Mac Dre was still a student at Vallejo’s Hogan High School, let’s the world know of his unwillingness to compromise for mainstream appeal, a promise he kept throughout his career.

By 1992, Mac Dre had recorded a number of EP’s and began his first independent label, Romper Room Records. At the same time, police were looking for the culprits in a string of robberies that targeted Vallejo pizza shops. Police said there had been 29 robberies in under eight months.

The case was highlighted in an episode of Unsolved Mysteries from March 4, 1992, where police said they believed the men belonged to a local gang called The Romper Room Crew.

Less than a month later, on March 26, Mac Dre was arrested for conspiracy to rob a bank. On that day, he’d decided to hitch a ride to Fresno with two friends so he could meet up with a girl he’d met while performing a show two weeks earlier. On the way back to Fresno, the car was pulled over and surrounded by officers from the Federal Bureau of Investigation as well as Vallejo police.

The police say that while Mac Dre was getting busy in a local motel with his lady friend, his accomplices were out casing a Fresno bank with plans of a robbery. But a local news crew had caught wind of the robbery over the police scanner and had prematurely gone to the bank. When Mac Dre’s friends saw the news crew, they called it off, according to documents provided by the FBI.

However, police still felt they had enough evidence to pull Mac Dre and friends over and charge the crew with conspiracy to commit bank robbery. Mac Dre was sentenced to five years for refusing to accept a plea deal. His accomplices were convicted of attempted bank robbery and given 10 years.

“They sent me to the pen for five years for a crime that was never committed/ I ain’t no bank robber but that five years had me thinking maybe I should have did it,” said Mac Dre on his 1998 song “Life’s a Bitch.”

Mac Dre was one of the first rappers unfairly targeted and prosecuted for crimes they never committed. Prosecutors used lyrics from the Young Black Brotha EP to help establish guilt in his case. While still incarcerated, Mac Dre re-released Young Black Brotha as his debut album in 1993, featuring a number of songs with vocals recorded through a jail phone.

He was released from California’s FCI Lompoc in August, 1996, and in the early 2000s he moved north to Sacramento to focus on music. It was an era marked by Mac Dre’s prolific post-prison recordings, where he created a dense body of work in such a short period of time that I once referred to him as the West Coast Max B.

No matter how long you’ve been a fan, there appears to be an endless supply of deep cuts and mixtape remixes to keep Bay Area rap historians satiated for decades to come.

The Wickedest Little City in America

Photo via KCPD

In December of 2011, nearly seven years after Mac Dre’s death, a number of music publications ran a story about a person claiming to have information about the still unsolved killing. The source of the story was Alonzo Washington, a Kansas City activist who has led numerous anti “stop snitching” campaigns, including one he did after Mac Dre’s murder, titled “Hip to give Tips.”

“I received a tip about a gun that was connected to the murder of Mac Dre,” Washington tells me in August 2020. “And I delivered it to the police. It was supposed to be in someone’s house, buried under something. I don’t remember the exact details. All I know is that I thought they should have been able to go get that gun.”

He’d found success solving Kansas City cold cases in the past. In 2004, he gave a tip to KCPD that helped solve the killing of four-year-old Erica Green, known to the world as “Precious Doe.”

Washington had been placing ads about the Green murder in the local newspaper. A family member of the victim had tried calling KCPD with information, but Washington says that he was shrugged off. They called Washington next.

He took the tip to KCPD and the case was solved not long after.

A culture of distrust exists between the Black community in Kansas City and the majority white police force that has been tasked to protect them. There’s little incentive to leave a tip when the police can’t be trusted to look into it, Washington said.

“The city doesn’t want the rest of the nation to know how violent things really are here,” Washington says. “That’s how my activism started. Some of these cases can be solved.”

This racial disparity is evident when watching A&E’s The First 48, a reality television show that follows various homicide detectives in the first two days after a murder. The show, and other shows like it, have been criticized for showing detectives that are predominantly white and victims that are predominantly Black. This overrepresentation of Black victims and suspects makes the white officers look like heroes.

Detective Everett Babcock is somewhat of a celebrity among his peers at the KCPD for appearing on The First 48 in the mid-2000s. He’s a large, personable man with graying hair and has been with the department since 1995.

He’s worked in the East Patrol Division, the Domestic Violence Unit, the Homicide Unit, the Mounted Patrol, the Generalist Squad and the Assault Squad, where he’s currently a supervisor.

In 2015, the KCPD Facebook page interviewed Detective Babcock as part of an officer spotlight series. One of the questions asked what his most memorable moments as a homicide detective were?

“When I was able to tell the families that their loved one’s killer had been brought to justice. That was always the big payoff moment for me as a detective,” he says. “The flip side of that was how bad you would feel when you couldn’t get a case solved and you would have to tell the victim’s family that there was nothing new. It’s beyond frustrating.”

Honeybear Productions

Photo via KCPD

By 2004, Kansas City and The Bay Area shared a mutual affection towards each other’s burgeoning hip-hop scenes, acting as the conduit to California for fledgling midwest rappers looking to gain access to a portion of the rap community previously unavailable to them.

For the Bay Area artists, Kansas City became like a second home, a tour stop that guaranteed sold out shows and fan adoration. The relationship between the two scenes is also a testament to Mac Dre’s allure. In Portland, Seattle, Las Vegas, and all throughout California, Mac Dre had garnered a similar following, earning cult-like status in local hip-hop communities across the West Coast and beyond.

In October of 2004, a Kansas City man named Damon Whitmill hoped to capitalize on Mac Dre’s popularity by bankrolling and promoting a rap show at what was then the Kansas City National Guard Armory.

It was the first and last time Whitmill would ever attempt to throw a concert and he was able to book three of the Bay Area’s biggest acts for a show on Halloween weekend: Yukmouth, Keak Da Sneak, and Mac Dre.

According to the police reports, Whitmill, who sometimes went by “Big D,” or “Honeybear,” spoke to Detective Babcock on numerous occasions, including the day after the murder. He’s a Kansas City native and allegedly a small-time drug dealer, according to witnesses and informants who spoke with Detective Babcock in the months following Mac Dre’s death.

In early October, he started a production company named “Honeybear Productions,” and enlisted the help of Kansas City rapper 40 Kal, who introduced the Bay Area artists to Whitmill.

In a police report that Babcock wrote in November 2004, Whitmill allegedly told the detective that Mac Dre agreed to come to Kansas City and perform two live shows for a total of $12,500, with the first $6,000 to be paid immediately as a deposit. Airfare, hotels and food while Mac Dre and crew were in town also landed on Whitmill, who sent a contract and the first payment early in October.

Once the show was booked, Mac Dre reached out to an old friend in Kansas City to see if he wanted to hang out and provide transportation for his crew over Halloween weekend. That friend was Savino Davila, who says he first met Mac Dre in the late 1990s through palling around with Yukmouth.

Davila is hispanic, with brown eyes and black hair. He wears a pair of glasses in most photos and his muscular physique reflects the time spent weight lifting during his period of incarceration. His father was murdered when he was just a kid.

Born and raised in Kansas City, Davila shared a close relationship with local hip-hop artists and was a regular at shows and studio sessions around town. He’s a self-described hip-hop head and his lifestyle in the early 2000s closely mirrored the crime-fueled stories present in the genre’s most popular music. While Mac Dre merely rapped about the lavish life of a major cocaine dealer — Davila actually lived it.

Davila is currently serving a 30-year prison sentence in Texas at FCI Seagoville, for being at the helm of a drug trafficking conspiracy that brought more than 330 pounds of cocaine into Kansas City between 2000 and 2006. He pled guilty in 2008.

“We were friends,” Davila says when I spoke to him in January. “He always called me if he was coming through K.C. He wanted more from me. He wanted me to get into music.”

Aside from a black Cadillac Escalade, Davila also owned a white van that he used for odd jobs around Kansas City. When Mac Dre reached out in early October, Davila offered to have his cousin, and good friend, Harold Piersey drive Mac Dre’s crew around on Halloween weekend. Piersey was also a fan of the Bay Area hip-hop scene and was willing to accompany Mac Dre whenever he needed a ride.

Davila and Whitmill had never met each other, with the latter telling Detective Babcock (in the police report) that Mac Dre’s transportation was provided by “some guys in Kansas.”

Whitmill used his own money to fund the October 29 show at the Armory, shelling out the $6,000 deposit before plane tickets were even bought. He hoped to sell enough tickets to double his money in a single night. He even set up a radio appearance and a record store meet-and-greet to help ensure the show’s success.

But Whitmill was a first-time promoter, and likely might not have known the amount of organization it takes to plan an event of this magnitude. And things quickly began to unravel when Mac Dre arrived.

Mac Dre Arrives in Kansas City

Photo via KCPD

Mac Dre and three friends flew from Sacramento to Kansas City, with a quick layover at LAX, on October 27, 2004. They were greeted at the airport by Davila, who picked the group up in his Escalade.

Davila brought Mac Dre to his hotel, where they hung out and listened to music. Mac Dre had been enjoying the success of his most recent album, The Game is… Thick, Part 2, and Davila was happy for his friend, looking forward to spending more time with him over the weekend.

Before he left, Davila arranged to have Piersey meet up with Mac Dre in the morning with the white van to help with transportation to his first scheduled events: a radio appearance and a record signing at a local music store.

While Mac Dre made his way through the city with Piersey, performing and appearing at different scheduled events, it was Whitmill who was responsible for making sure he got paid and that everything went according to plan.

It was also Whitmill who scheduled the club appearances and shows for the weekend. Unlike Davila and Piersey, Whitmill was the only known person with a financial incentive to have Mac Dre show up on time and fulfill his responsibilities.

According to Whitmill’s interview with Babcock, Mac Dre missed his radio appearance and showed up late to the record store signing at Much Music and More on October 29. Detective Babcock interviewed the store’s owner, Byron Robinson, a week after the murder.

Robinson was initially excited about the signing — until Mac Dre showed up an hour and a half late with an entourage of 22 people. The record store owner told detectives that fans were getting antsy and it all felt very unorganized. Mac Dre left only 30 minutes after he’d arrived and by the end, Robinson had regretted hosting the event.

The record signing and radio appearance were both meant to promote the October 29 concert at the National Guard Armory. Whitmill bet his own money on the success of this concert and worked to lower costs by hiring members of his own family to collect tickets and provide security.

Whitmill told Detective Babcock that Mac Dre didn’t show up at the Armory until 30 minutes after he was supposed to finish performing, causing Whitmill to have to rent the venue for another hour. On top of that, Mac Dre’s crew of over 20 people rushed the stage mid-show, creating a security concern, and causing everything to get shut down.

Gary Edwin, who performs under the name DJ Fresh, was working as the sound man and DJ for the show that night. He told detectives that he had to shut off the music multiple times because of people crowding the stage.

At one point, DJ Fresh said he mentioned to Mac Dre that if he told people to get off the stage they might listen to him since they were his fans. Mac Dre responded “that’s not my job,” and the club’s security reportedly shut it down.

DJ Fresh had gotten hired to do the show about a week in advance after receiving a call from a man who introduced himself as “Big D.” According to Babcock’s police report, Fresh later picked Whitmill out of a photo lineup, confirming that he was the promoter that had hired him.

In January 2021, DJ Fresh said he doesn’t remember Whitmill at all and that he normally doesn’t remember people if he only worked with them one time.

In his first interview with detectives taken the day after the murder, Whitmill states that he lost money. He later took it back, saying he broke even but that he had expected to make much more. When the detective asked for a third time if Whitmill made any money on the first show, he once again changed his story, saying that he did pretty well, profiting nearly $6,000.

Detective Babcock interviewed numerous witnesses from that night — including members of Whitmills family — and many reported seeing a similar series of events: Mac Dre showed up late around 11:30 p.m. and the show eventually shut down due to people crowding the stage.

Local crews opened up the show, according to DJ Fresh, including 40 Kal, who introduced Whitmill to the West Coast artists.

The show at the Armory took place on a Friday. Both Yukmouth and Keak Da Sneak left Kansas City the next day without being paid the full amount they were promised for performing. They were told that they’d get the rest of the money wired to them later in the week. It’s unclear if that ever happened.

For whatever reason, Mac Dre decided to stay in Kansas City that weekend and agreed to perform at a VIP Halloween party at the former Atlantic Star on 95th and Hillcrest on Sunday night. Whitmill told Detective Babcock that he’d hoped the Halloween party would help make up the monetary loss from the show at The Armory.

For Whitmill, it was a last ditch effort to avoid losing a couple thousand dollars over a failed weekend (at least if you go by his first statement to the detectives). The event he had planned went poorly and he hoped this would make up for it. He even rented a limousine to transport Mac Dre to and from the Atlantic Star.

DJ Fresh told detectives in the weeks after the murder that Whitmill had called him at the last minute to set up sound and DJ at the Atlantic Star on Halloween night. He doesn’t recall hearing from Whitmill again.

Mac Dre once again showed up late. He stayed for only 30 minutes, according to Whitmill, before abruptly leaving without performing.

Savino Davila was at the Atlantic Star earlier in the night, before he left to take his kids trick or treating. He told Detective Babcock in 2004 that he spoke with Mac Dre while in a limousine in front of the club. Mac Dre told Davila he was annoyed because the event wasn’t organized and because there were other local rappers performing. Mac Dre then said that he “didn’t feel safe” and was about to leave.

Davila said he asked Mac Dre if he needed anything else. He said “no,” and then they both left.

He would later tell Detective Babcock that Whitmill was angry after Mac Dre left without performing. Whitmill called off the limousine service and called Davila to see where Mac Dre was.

Davila took his kids trick-or-treating and Mac Dre went to a local IHop for food. The limo was gone, but the white van driven by Harold Piersey was there, following behind.

Detectives were later told that just before the murder, Mac Dre had been waiting to meet up with Whitmill to receive his final payment — but Whitmill never showed.

When they finally left, Mac Dre got in the back of the van and instructed Piersey to drive them to his hotel. They had to make a brief stop at The Baymont, a hotel where members of Mac Dre’s crew were staying, before heading to The Sheraton. Mac Dre was so tired that he lay down in the back of the van, where Piersey believes that he quickly fell asleep.

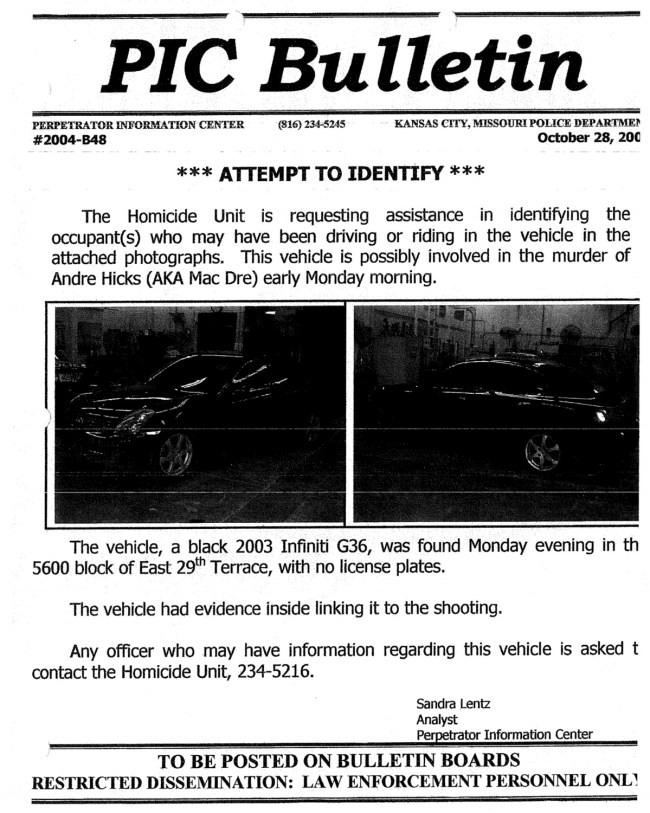

At around 2:30 a.m, the white van was traveling northbound on Highway 71 just south of 75th street, when a dark sedan pulled along the drivers side of the van and unloaded upwards of 30 bullets from two seperate guns: an automatic rifle and a .45 pistol. The sedan violently rammed the driver’s side of the van in between taking shots at it.

Piersey swerved off the highway and into the oncoming lanes, before crashing into a ditch, where Mac Dre’s body was thrown from the car. Piersey claimed that he never heard a sound from Mac Dre.

Losing consciousness for a brief moment, Piersey claimed to have lost his cell phone in the crash and tried climbing out of the embankment, where he noticed another car aggressively charging towards him.

He fearfully ran the other way, eventually ending up back at The Baymont 45 minutes later, where he told the front desk worker to call the police. He then ran upstairs and told Mac Dre’s friends what happened. They left immediately to go find his body. The front desk clerk would later report seeing four males and three females leave the hotel sometime after 3:30 a.m.

Nearly an hour passed before police arrived at the accident. Mac Dre was dead when they got there from a bullet wound in the back of his neck. Detectives eventually counted 30 bullet holes on the driver’s side of the van, with copper bullets still lodged in two of the holes. They counted a total of 3 exit holes on the passenger side as well, with most of the windows getting broken in the process. The van was completely totaled.

Responding officers found shell casings for two separate weapons, multiple 7.62X39 Wolf shell casings, as well as two .45 Caliber spent shell casings. People were interviewed at the scene, including a pair of women who came upon the accident, before heading to a nearby gas station to call it in.

It seems hard to believe that Mac Dre could end up lying dead in a muddy ditch for more than an hour after crashing in such a violent way. More than 30 shots echoed in the night and yet nobody heard or called anything in until Piersey made it to The Sheraton.

He died alone in Kansas City, thousands of miles away from his home in Sacramento; thousands of miles from the streets of Vallejo and San Francisco, where thousands of people still cling to his every word. It seems such an unceremonious way to go for a larger-than-life personality like Mac Dre. A cosmic wrong that forever threw the world off balance for those who knew him best.

Infiniti Mystery

Photo via KCPD

Mac Dre was still lying in the mud, covered only with a tarp, when KCPD Detective Everett Babcock arrived at the scene the next morning. He searched the rapper’s pockets and found an electronic hotel key for The Sheraton, and a membership card for a 24 Hour Fitness under the name Andre Hicks.

The crime scene spanned several hundred feet and it appeared to Detective Babcock to be a targeted hit. Along with dozens of bullet holes, police also found that the driver’s side of the van had been rammed by the other vehicle during the shooting. What happened here had been loud and violent.

Detective Babcock went to The Sheraton to search the room belonging to Mac Dre. When he arrived and unlocked the door, he discovered a group of men were standing in the center of the room, rifling through a suitcase.

He made the men drop everything and then told them to leave. This was perhaps the first time Detective Babcock realized Andre Hicks was more than your average Kansas City murder victim. He found a computer and recording materials, as well as dozens of Mac Dre CDs originally meant for a merch table.

Detective Babcock spoke with the promoter, Damon Whitmill, two times in the weeks after Mac Dre’s murder. He asked him if he’d submit a DNA sample to help with the investigation. Whitmill said that he’d need to check with his lawyer, Kansas City defense attorney Carl Bussey, before submitting to a mouth swab.

According to the police records, Detective Babcock ran into Bussey 10 days later, on Nov. 22, outside of the KCPD headquarters. He asked Bussey if Whitmill was ever going to provide that DNA sample. Bussey said that his client did not wish to provide the sample, saying that Whitmill was afraid that his DNA would be put in a database for comparisons to other crimes.

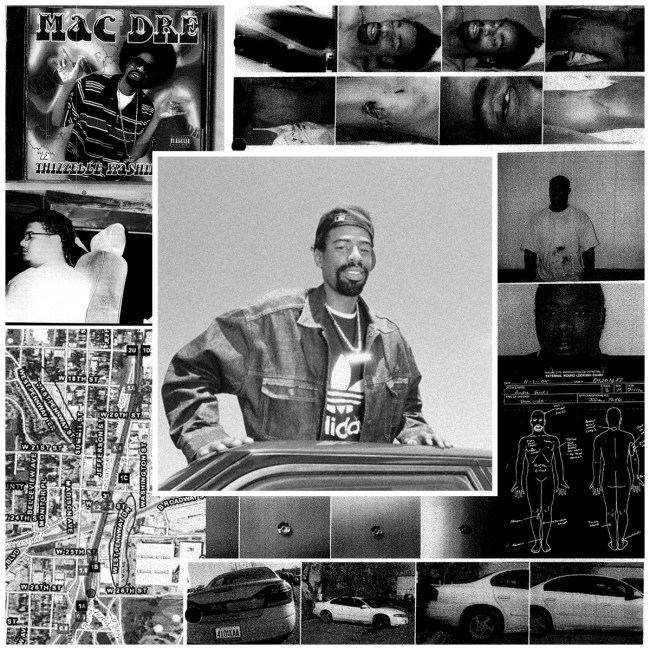

The first real tip came the day after the murder, when Detective Babcock was contacted by the local media, who told them that a man had reached out with information about a car.

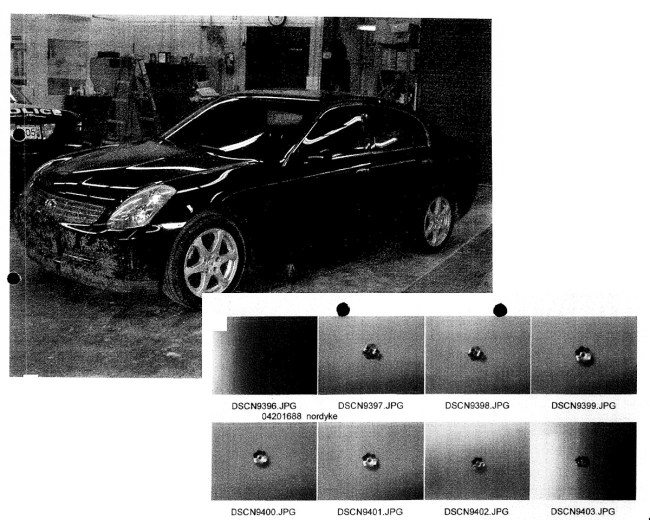

The tipster had tried to reach Kansas City police, but couldn’t get through. He next called 41 Action News, the local television station, and told them he saw two black males between the ages of 20 and 30 ditch a black Infiniti behind his house, get out and then get into a faded blue van with tinted windows, before leaving. The witness didn’t see the driver.

The news station contacted Kansas City police and the car was located by 6 p.m., about 15 hours after the shooting took place, and it, too, was totaled.

Detective Babcock saw four bullet holes near the back seat on the passenger side. It was clear they were firing from inside the vehicle by the way the metal from the car door curled outward. There was also mud all along the bottom of the vehicle.

There were three spent 7.62X39 Wolf shell casings found in the backseat — the same kind located at the crime scene. There was white paint all along the passenger side of the car, suggesting that it had been used to ram a white vehicle.

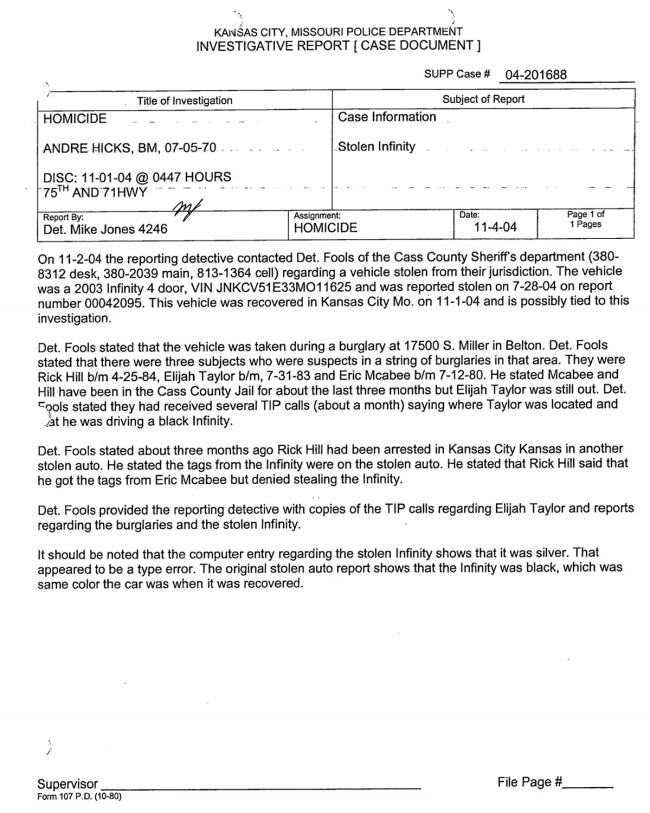

Detective Babcock learned that the black Infiniti had been stolen out of a garage in Belton, Missouri the previous July. Police in Cass County had received multiple tips that a small-time criminal named Elijah Taylor had been seen driving the car in the months leading up to the murder.

But it’s no wonder why the police didn’t find the car. Detectives noted in the investigative report that the computer entry for the stolen Infiniti showed the car as being silver, instead of black.

“That appeared to be a type error,” wrote KCPD Detective Mike Jones in an investigative report dated November 4, 2004.

Taylor was interviewed by Detective Babcock nearly a year later at the Wyandotte County Jail, where he was being held on theft and robbery charges and outstanding warrants. Taylor wasn’t surprised to be speaking with detectives, having seen the black Infiniti on the news during reports of Mac Dre’s murder.

The first time Taylor laid eyes on the stolen black Infiniti was in July of 2004 — several months before the murder — according to his interview with Detective Babcock. It was being driven by a friend of his named Rick Hill. He was pretty sure Hill had stolen the car, but he didn’t want to pry. Hill would later ditch the Infiniti, telling Taylor that he sold it to a man named “Papoose.”

Taylor then told detectives a story that they aren’t certain they believe.

He said that one day after July, the black Infiniti pulled up alongside him as he walked down the street, near 52nd and Paseo, in Kansas City. He didn’t recognize the driver, but assumed it was Papoose, because that’s who Hill said he’d sold the car too. He also noticed that the Infiniti now had tinted windows.

Taylor said he asked the driver for a ride to 56th and Highland and the driver agreed. Detectives told Taylor that it seems strange that someone he didn’t know would pull up alongside him for no reason and then give him a ride. He said he knows how it sounds, but that’s what happened.

Detectives then showed Taylor three photo line ups. In the first one, he picked out a man named Calvert “Papoose” Antwine II as being the driver of the Infiniti that day.

Streets Are Talking

Photo via KCPD

While Detective Babcock attempted to locate the driver, or drivers, of the black Infiniti, whispers of a Halloween weekend altercation between Mac Dre and Kansas City rapper, Anthony “Fat Tone” Watkins, began to pick up steam in the local rumor mill.

The character arc of Fat Tone could be viewed as a prime example of what happens when “keeping it real,” goes wrong. In the early 2000s, he’d begun gaining popularity for both his music and his rap sheet in equal measure.

In 2001, at the age of 20, Fat Tone was arrested and charged with the double-homicide of a 19-year-old girl and her unborn child. He served nine months in jail before the charges were dismissed, with prosecutors complaining that the witnesses refused to cooperate.

Fat Tone did little to quell the rumors of his menace. His image as a violent gangster helped him sell records, which is ironic, considering that music was probably one of the few hustles helping Fat Tone escape a life of crime.

And his music was good. His brash, violent and honest take on midwest hip-hop captured the ears of his Bay Area contemporaries in a way other Kansas City rappers hadn’t. Mac Dre and Suga Wolf recorded a song with him for his 2002 album, Only in Killa City, titled “Cut Throatz.” They were friends — and they stayed in touch enough for Fat Tone to know that Mac Dre was coming to town for Halloween weekend.

Witnesses say they saw Fat Tone arguing with Mac Dre over stage time at the National Guard Armory show on October 29. Dozens of tips recorded by KCPD feature some variation of Fat Tone and Mac Dre getting into an altercation. However, numerous witness statements say this never happened and police were never able to confirm it.

Fat Tone and his lawyer met up with Detective Babcock on November 16 and denied any involvement in the murder, while acknowledging that he’s heard the rumors about his alleged involvement.

He tells Detective Babcock that every time something like this happens, he gets blamed and that he isn’t worried because he knows he did nothing wrong.

According to Fat Tone, he’d hung out with Mac Dre and friends at a hotel the day after they arrived in Kansas City. He’d also been to the show at the Armory and remembered Mac Dre briefly inviting him on stage.

When speaking with detectives in the weeks after the murder, DJ Fresh, who was the soundman and DJ that night, remembered Fat Tone briefly hopping on stage after being invited up by Mac Dre.

“Fat Tone was West Coast-friendly,” DJ Fresh says. “He was the one everyone knew about over there.”

In a February 2021 interview, the Kansas City rapper Mr. Stinky said that he threw a show at the Atlantic Star the night before Mac Dre’s murder, which only added to the confusion later on.

“It’s all tangled up,” Mr. Stinky says. “He died on Halloween night and I was throwing a Halloween party the night before and what makes it even crazier is that Fat Tone shows up to my party and gets into a fight with someone later that night. So everybody’s names are intertwining.”

Mr. Stinky said this incident helped lend credence to the numerous rumors that Fat Tone had gotten into a confrontation with Mac Dre that weekend, even though he says it never happened.

Several months later Fat Tone would release a song where he denied having any involvement in Mac Dre’s murder. However, rumors persisted that Fat Tone actually released a song admitting to the crime — although it’s never been found.

“Fat Tone had a reputation,” says Kansas City activist Alonzo Washington. “It wasn’t like he was the greatest rapper in town, but he would be getting into a lot of trouble with the law and so he had this sort of edgy thing with his music. He used Mac Dre’s name to get a little more street cred for his career. But I don’t think he did it.”

In an interview with Kansas City’s The Pitch from 2005, Detective Babcock said that he’s convinced that Fat Tone did not kill Mac Dre.

However, that didn’t stop Fat Tone from facing deadly consequences over the unfounded rumors and on May 23, 2005, seven months after Mac Dre’s killing, Fat Tone and his friend, Jermaine Aikens, were murdered in Las Vegas in what is widely believed to have been retaliation for Mac Dre’s death.

This is where Mac Dre’s death becomes the catalyst for the shooting deaths of three people, with two others being given life in prison, effectively losing their lives as well.

It’s a story that lives at the intersection of an extremely strange time in hip-hop history. One of the men convicted of killing Fat Tone was a fledgling rapper and rap promoter named Andre “Mac Minister” Dow, who recorded the spoken word portion of the intro to The Game’s sophomore album, Doctor’s Advocate, while on the run for killing Fat Tone.

Mac Minister was a suspect in the murder of a call girl from Utah named Lee Danae Laurson. After being featured on an episode of America’s Most Wanted, Dow was arrested in San Francisco in March 2006. He was later convicted of two counts of first-degree murder and two counts of conspiracy to commit murder in 2008 (for the murder of Fat Tone and his friend, Jermain Watkins) and is serving a life sentence in a Nevada State prison. Although Mac Minister maintains his innocence, the judge decided to uphold his life sentence in 2010 after Dow’s lawyers argued that mistakes were made during trial.

While the tips regarding Fat Tone’s culpability continued to flood in, Detective Babcock was convinced that he had nothing to do with it and started spending his time on more credible theories.

In the years after Mac Dre’s murder, Detective Babcock began to hear rumors that Damon Whitmill, the promoter who paid to fly Mac Dre to Kansas City, might have also paid to have him murdered.

In 2008, Detective Babcock spoke with a jailhouse informant, David Thibeaux, while he was in federal custody on unrelated charges at the Charles Evans Whittaker Federal Courthouse.

In his interview with Babcock, Thibeaux said that he grew up with Whitmill in Kansas City and that he’d heard him bragging about sending people to kill Mac Dre over a failed concert arrangement. He also provided names for the supposed shooters. One of those names was Papoose, who Detective Babcock remembered from his interview with Elijah Taylor, who said Papoose was the nickname of the person seen driving the stolen black Infiniti.

During the police interview, Thibeaux also says that Whitmill made a concerted effort to spread rumors that Kansas City rapper Fat Tone had been responsible for the killing, even though Whitmill knew he was innocent.

Informants and Eye Witnesses

Photo via KCPD

Aside from Thibeaux and Taylor, over a dozen witnesses and informants reported seeing Calvert “Papoose” Antwine II driving the black Infiniti, with multiple witnesses saying that he even paid to tint the windows in the month before the murder.

Antwine’s father is infamous in Kansas City as the drug dealer and convicted murderer who narrowly avoided the death sentence in 1995 in a case that went all the way to The Supreme Court.

The senior Antwine was convicted and sentenced to death for the murders of two brothers, George and Winston Jones, on Nov. 11, 1983. Court documents identified the brothers as drug dealers and Antwine was said to have worked with them. He shot Winston to death and was arrested with George as the two men struggled over a gun. The KCPD then, for some reason, locked both men in the same holding cell.

This is an excerpt from a court opinion published in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit describing what happened next:

“Five or ten minutes later, an officer heard some yelling and looked into the holding cell to find George lying face down on the floor, bleeding from the nose and mouth, and Antwine sitting on a bench a few feet away. The officer checked on George, then stepped away to call for help; when he turned back, he saw Antwine in midair, coming down with both feet on George’s head. George died from head injuries a few days later.”

Antwine pled guilty to murder and was sentenced to death. He later appealed his sentence, saying that prosecutors unfairly argued that putting him to death would be cheaper to taxpayers than housing him on death row. The prosecutor also said that the death would be painless, which defense for Antwine argued was untrue and manipulative to the jury. The Supreme Court refused to reinstate the death penalty.

The junior Antwine was born in 1981, only two years before his father murdered the Jones Brothers. Antwine is no stranger to the legal system himself. He has a lengthy criminal record in Missouri dating back to 1999, when he was first arrested for selling drugs within 1,000 feet of a school in Kansas City.

The first time Antwine was mentioned in the documents was on December 10, 2004, when an unnamed person told police that their cousin stole the black Infiniti and then later sold it to Antwine in “June or July,” of 2004.

Antwine and a friend asked them if they wanted to go to a rap concert on the night Mac Dre was murdered, according to the anonymous tip. The tipster declined and later saw both Antwine and the other man burning their clothes in an alleyway visible from their house around the time of the murder. After that night, the black Infiniti was gone.

On July 25, 2005, Detective Babcock interviewed Kalise White, a woman who had just been jailed on drug charges. She knew Antwine and said he’d given her rides in the black Infiniti in the month before Mac Dre’s murder. She also said he’d paid to get the windows tinted and assumed some girl had rented it for him.

A separate informant told detectives on March 3, 2006 that he had heard about Antwine bragging about being paid to kill Mac Dre while incarcerated at CCA Leavenworth. The informant said he’d never heard Antwine say it himself but that he’d heard his friends, including a man named Ta’ron “T-Baby” Smith, talking about it.

Smith was also mentioned as having been seen with Antwine in the black Infiniti numerous times in the months leading up to the murder.

And according to Missouri state court records, Smith and Antwine were arrested together less than six months after Mac Dre’s murder, on March 7, 2005. They’d been spotted by KCPD in a stolen van near 59th Street and Blue Hills Road, and had attempted to evade police by jumping out and hiding in a nearby backyard. Police found drugs and multiple firearms, including an AR-15 assault rifle — the same type of weapon used in Mac Dre’s shooting.

Yet another informant, Nicolas Bell, also incarcerated at CCA Leavenworth, told detectives a similar story on March 13, 2006.

Bell’s lawyers had reached out to detectives saying that their client had information regarding two murders, Mac Dre’s being one of them. In March 2006, Bell told detectives that Antwine and Smith had been bragging about the murder, saying that Smith had told him that he’d been paid $10,000 to perform the hit. Bell told detectives he’s not sure what to believe, considering that everyone said that they had something to do with the murder at some point.

Detective Babcock met with Antwine numerous times in the years after the murder and he repeatedly denied having any involvement.

But on March 13, 2006, Antwine finally admitted to detectives that he had been in possession of the black Infiniti used in Mac Dre’s murder. He claimed to have sold the car to Fat Tone on the day before Halloween. Detective Babcock noted that he didn’t believe Antwine was being truthful.

Almost 10 years later, Antwine was murdered in an incident eerily similar to Mac Dre’s death. In March 2014, local news reported that Antwine had been found dead in an upside down SUV riddled with bullets. Police said the car crash happened as a result of the victim attempting to flee a shooting. According to KCPD, witnesses said they heard gunshots before seeing a silver Dodge charger leaving the scene.

Kingpin

Photo via KCPD

In the years after the murder, Detective Babcock spoke several times with Savino Davila, reputed to be one of Kansas City’s largest cocaine dealers at the time, and the owner of the white van that Mac Dre had been riding in at the time of the shooting.

Davila was convicted in 2008 of being at the head of an organization of more than 30 people who brought in approximately 330 pounds of cocaine between 2000 and 2006. Friends with Mac Dre, Davila had been the one entrusted to pick him up from the airport when he arrived in Kansas City. It was him who had arranged to have his cousin and good friend, Harold Piersey, provide the transportation to Mac Dre and his friends over Halloween Weekend, free of charge.

When Detectives first spoke with Davila, he maintained that he saw Mac Dre at the Atlantic Star on Halloween night, but left early to take his kids trick or treating. He didn’t hear about the murder until the next morning.

His story completely changed in 2008, after he was arrested for drug conspiracy and looking at 30 years in prison. Detective Babcock also spoke with several jailhouse informants that Davila had allegedly been communicating with while awaiting trial at the Leavenworth Detention Center.

One of those informants was Gary Patterson, who told Detective Babcock that he became friends with Davila while they were housed together in 2007.

Patterson told Detective Babcock that Davila was trying to leverage information he knew about the Mac Dre murder to make a deal for leniency in his upcoming drug conspiracy case.

According to the police reports, Davila told Patterson that on the night of the murder, he was with Mac Dre at the Atlantic Star. He said that the promoter, Damon Whitmill, who Patterson referred to as “Damon” or “Big D,” became mad at Mac Dre after he refused to perform, instead showing up late only to do a 30 minute walk through before leaving.

According to his story, Whitmill then sent Calvert “Papoose” Antwine II and Ta’ron “T-Baby” Smith to kill Mac Dre, which they allegedly did with two separate guns and driving the black Infiniti. Another informant from Leavenworth shared a similar story with Detective Babcock. He said that Davila had approached him for help writing a letter to detectives. Davila wanted to give detectives info about the murder without implicating himself.

The informant told Detective Babcock that Davila called Piersey, the driver of his van that was transporting Mac Dre, to find out their location for Whitmill, who then sent the shooters to attack the van, resulting in Mac Dre’s death. (Despite multiple attempts to reach out, Piersey could not be found for comment).

Davila wanted to leave out that last part for fear of incriminating himself, according to the informant. He said that Davila wanted to have either someone say that they were with him that night and vouch for a different version of events where Davila was following the van and actually saw the murder with his own eyes. This version of events was meant to take the blame off Davila, while still providing enough answers to hopefully strike a deal to get out of prison early.

In an interview conducted this past January, Davila denies ever speaking about his case with other inmates.

“That can’t be true,” Davila says. “I never discussed anything with anybody at Leavenworth. When guys are incarcerated, they try to come up with these schemes and these stories to try and help themselves. That’s just what they do. It’s part of the culture.”

Jailhouse snitches are notoriously unreliable. Their motives for justice and truth are almost never pure and their voluntary statements should be taken with a grain of salt.

But Davila spoke with more people than just jailhouse snitches and in 2008, he shared a version of events with Detective Babcock that could have solved this case more than a decade ago — had he decided to follow through with his statement.

“I Just Couldn’t Do It.”

Photo via KCPD

In his final interview with Detective Babcock in 2008, Davila implicated Damon Whitmill as having ordered the hit on Mac Dre, with Antwine “Papoose” Calvert II and Ta’ron ”T-Baby” Smith as the actual shooters.

“After talking with the detectives I went back to my cell and laid down. I thought about my life and how I ended up talking to them and realized that it wasn’t me and that I wasn’t raised that way,” Davila told me in a January 2021 interview. “I just couldn’t be responsible for putting another man behind bars. I couldn’t do it. I could have gone home off of that case, but it just wasn’t me.”

Davila recanted his previous story and told Detective Babcock that he returned to the Atlantic Star after taking his kids trick or treating. Later that night, he said that he was following his white van as the driver, Harold Piersey, took Mac Dre back to The Sheraton after leaving IHop.

Davila told Babcock that he remembered seeing a black Infiniti pass his car, before witnessing Antwine hanging an automatic rifle out of the passenger side window, shooting recklessly into the driver’s side of his white van.

Then, according to Davila, the driver of the infiniti “side-swiped” the van. This stuck out to Detective Babcock since the vehicle ramming hadn’t been information released to the public.

To be fair, there are pieces of Davila’s story that don’t quite add up. After witnessing the shooting, Davila said he turned off his phone, took the nearest exit, went home and went to sleep. This isn’t how you’d expect someone to act after witnessing their own van being shot up with a friend and family member inside.

In January 2021, Davila told me that he wouldn’t directly comment on his statement to Detective Babcock.

“For legal purposes, I’m not sure what to say. I don’t want to implicate myself in something that’s not true,” Davila says. “I think someone’s got it misconstrued. Parts of it are right, parts of it are wrong.”

Based on all my investigations, it seemed to suggest that the statement that Davila gave Detective Babcock was only partially true. He knew what happened to Mac Dre and felt partly responsible, but couldn’t bring himself to testify in court. That’s why his statement went no further than the investigative reports of Detective Babcock.

If you trace the trail of police reports, you arrive at this summary of the facts: on the night Mac Dre was murdered, he was supposed to do a club appearance. Whitmill hoped that Mac Dre would actually perform instead of just appear, in order to make up losses accrued over the weekend. Instead, Mac Dre showed up late again, only stayed for 30 minutes and then left without performing.

Davila called his driver and found their location. He called Whitmill back and told him and then Mac Dre ended up dead. Davila seems to feel guilty for the role he played in his friend’s death and has tried to find ways to tell detectives since getting arrested in 2006. Although he denies it, two jailhouse snitches claim he asked them to vouch for a version of events that doesn’t include his phone calls with Whitmill.

He even went so far as to tell detectives that he witnessed the shooting himself and then went home, turned off his phone and went to bed. This is unlikely and detectives know it. But why make up that lie at all? Unless Davila wanted the truth to be out without implicating himself.

“I feel bad because I know Dre’s family would have wanted to get justice for him,” Davila says in January 2021. “But I just couldn’t do it, that’s why the prosecution on my case was so upset with me and ultimately, why they sentenced me to 30 years.”

Davila continues: “I’m truly sorry about not being able to provide that sense of peace for his family and that those guys weren’t held accountable for that senseless crime.”

Taron “T-Baby” Smith was shot and killed on the morning of June 12, 2010. His body was found in a light colored Chevy Blazer at the intersection of 73rd and Indiana, near the Noble and Gregory Ridge area of Kansas City, Missouri.

Just like Antwine, Kansas City Police never arrested anyone for Smith’s murder and there’s no proof that it’s connected to Mac Dre’s shooting.

Damon Whitmill could not be reached for comment.

Ahead of His Time

In 2011, Mac Dre received an influx of new fans after Drake gave him a shout out in his hit single, “Motto” featuring Lil Wayne. In 2016, Drake even brought out Mac Dre’s mother, Mac Wanda, at a sold-out show he did at the Oakland Arena in 2016 for his Summer Sixteen Tour.

Mac Dre was an artist ahead of his time. He started a video blog series in the early 2000s called “Treal TV,” that features some of the best footage of Mac Dre available. He would have easily adapted to the age of social media.

“Mac Dre would have been larger than Snoop,” Sleep Dank says. “I put that on everything. He was on his way. I would have had a house right now. If Dre was alive I’d be in a big ass house right now.”

When Mac Dre died everything changed for his family and friends. He was the center of his community; a guiding light that acted as a beacon for those closest to him. He symbolized hope for a lot of people who came from the same poverty stricken areas as he did. When he died, a certain momentum was killed with him and he left a void that’s still yet to be filled.

“Whatever happened, happened, you know what I’m saying?,” Sleep Dank says. “He’s the one that kept us all together. He was the first person to show my neighborhood that we don’t have to sell crack anymore. That you don’t have to get your hands dirty.”