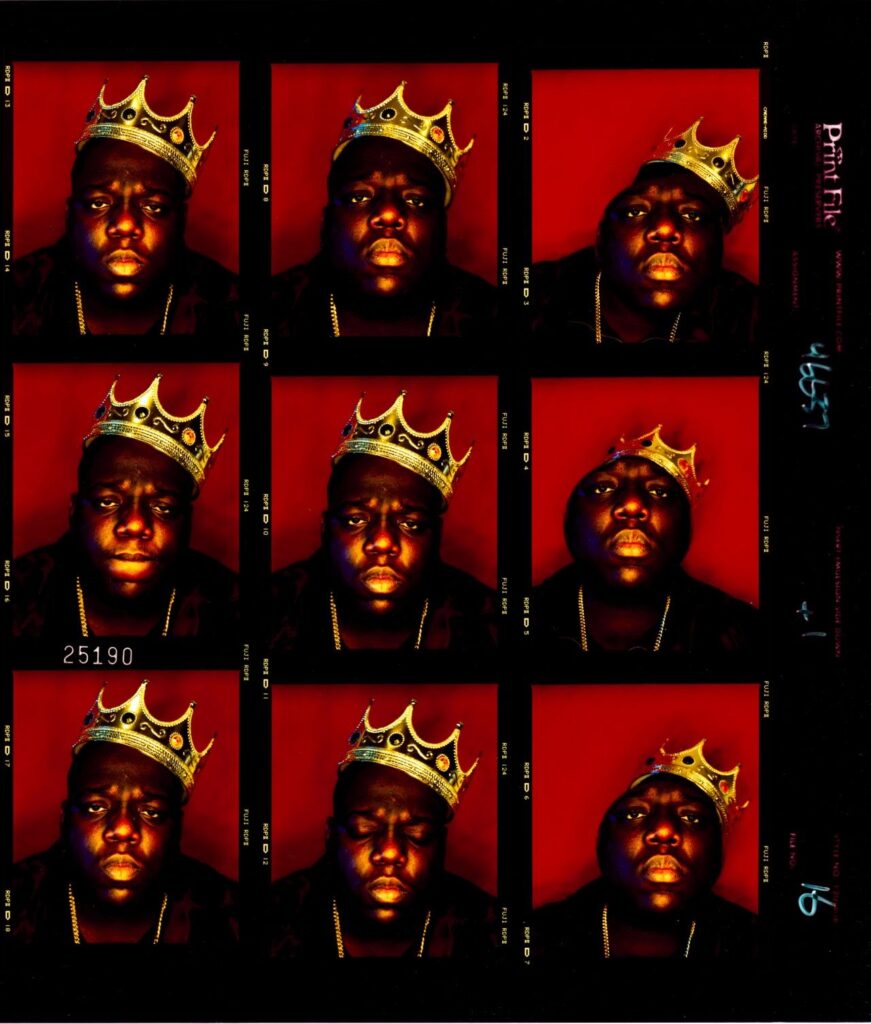

Photos by Barron Claiborne

It’s easy to lose Christopher Wallace in mythology. Because he died so young, and left such an impossible body of work, because of legends those who were around him in his brief lifetime continue to tell, his presence has become larger than life in our imaginations. In New York, the places where he lived, where he walked, where he hung out, and where he recorded have become holy places, ordained sites. A belt he wore and once happened to leave behind in an office at The Source took on talismanic properties, passed down from editor to editor through generations of staff at the iconic magazine. He’s the closest thing hip hop has to a patron saint. But his monumental legacy doesn’t come from some godlike, alien greatness, but from his endlessly endearing humanity.

When we discuss Christopher Wallace as the GOAT, we use all the wrong language and ask the wrong questions . While we debate merits and sample size and Puff, and Faith and Pac, the question isn’t “IS Biggie Smalls the Greatest rapper who ever lived?”, but “CAN Biggie Smalls BE the greatest rapper who ever lived?” If your answer is no — that there just isn’t enough to qualify him among rappers who achieved generational longevity like LL Cool J, Lil Wayne, or Jay-Z — it’s a brief and simple conversation. If the answer is yes, the conversation is equally brief and simple.

Biggie simply presents the most unique, astonishing, baffling body of work we’ve ever had to consider as nerds who live to argue about inane bullshit and rank things. With the possible exceptions of Big L and Big Pun, who didn’t quite put together the formal body of work in the same tragically brief period of time, there’s no career to even compare him to. No other rapper offers such an unorthodox challenge to the question of quality over quantity. So let’s attempt crossing genres to find historical counterpoints. Biggie has slightly older peers in the infamous 27 Club. But The Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones had three albums in a collective — as did Hendrix. Nirvana had three proper albums and a historic MTV Unplugged session. Biggie’s closest musical counterpart in terms of resume is probably Amy Winehouse, a brilliant artist and writer, but she only gave us 25 proper songs, basically the length of Life After Death to assess, before passing on.

Let’s widen the aperture on the question of greatness itself. There’s no real comparison in sports, with the possible exception of Len Bias, who never got to the league. But as a thought experiment, I’ll present Biggie as a hypothetical athlete: Imagine a rookie who enters the NBA, wins Rookie of the Year, MVP, Defensive Player of the Year, leads the league in points, rebounds and assists, and wins the championship. Then this player comes back the following season, does it all again with Most Improved Player replacing Rookie of the Year, ends the NBA Draft and the salary cap due to its inherent unfairness and labor rights violations, and then dies.

Imagine an American politician who rises from obscurity, runs for president as his first attempt to be elected to any office at the earliest possible age, wins all 50 states in a landslide, solves Universal Health Care, achieves common sense gun regulations, raises the minimum wage to $25 an hour, ends our foreign wars, achieves statehood for Palestine, runs for a second term, wins by a greater margin, packs the Supreme Court, turns D.C. and Puerto Rico into states, abolishes prison and the police, and then dies.

You have to go far, far afield to find an artist who presents the same knotty challenge. The 19th Century French poet, writer and enfant terrible, Arthur Rimbaud, published an incredibly small body of work in his lifetime, only a bit more than that output was released posthumously, and all of it had a staggering, outsized impact on writing and thought for generations after. He also died 13 years older than Biggie ever got to be.

Biggie’s body of work contains 42 proper songs (depending on how you qualify “B.I.G. Interlude”, considered in this context as a proper song), 36 guest verses (depending on how you qualify his work with Junior Mafia, presented here as guest work), a handful of demos and freestyle verses and interludes, and they’re all relatively perfect. He came into this world fully formed, as brilliant, confident and commanding as a teen rapping in Clinton Hill and Bed Stuy basements and street corners as he was on his final atmospheric mission statement album closers. The margin between his best and worst work is as thin as we’ve ever seen, and the very worst would rank as the absolute best most of his peers in your top 10 could ever muster.

You’ll see Biggie’s lyrical exhibitions — songs that were exercises in pure spit, with little thought given to the hook or concept or commercial viability — weighted towards the top of this list. But he was also rap’s greatest storyteller and dramatist. He was among rap’s greatest pop musicians, effortlessly tossing off hooks and formal mainstream smashes that were witty, raunchy, and catchy at a time it was very difficult for even great rap songs to connect with national audiences. Aesthetically, he had the greatest voice any rapper ever had. The greatest flow, a percussive semi automatic weapon he fired at the mic like Max Roach beating a snare. He was a gravitational presence no matter how minor his contribution on a track.

His wordplay wasn’t just clever, communicating his intelligence and eye for detail, he also had a flare for the beauty of language. His first few bars were always enthralling ad instantly seared into your brain. And finally, a controversial take I simply can’t leave out of his resume conversation: Hardcore is partially Biggie’s great lost album, and as a work of creative crime fiction, perhaps his most impressive and imaginative effort.

The challenge with Biggie comes to breadth. Is it really fair to say a guy who died a few months into his 24th year — with two proper albums in the can — is greater than an artist like his brother and rival Jay-Z, who was three years older than Big and has been releasing, if not great, at least relevant music for the length of Biggie’s entire life? He was notoriously stingy with his brilliance. It’s the dearth of material, the unanswerable questions. Even his tossed off radio freestyles all eventually became album verses, and can you blame him? If you had an immaculate verse people will be reciting for generations, would you really just let it live on a Stretch and Bob bootleg only a handful of New Yorkers had access to during Big’s lifetime?

The saddest part of this exercise for me is its possibility. We shouldn’t be able to rate every song, all the tossed off appearances and skits and loosies, that the greatest rapper who ever lived made in a readable and coherent internet list. This should be a masterwork of criticism, something that takes a great scholar years of thought and effort and hundreds if not thousands of pages to contextualize and grapple with. But that’s the sad brevity of what Big left behind.

While that fact is crushing, it’s a testament to Big that it doesn’t diminish just how impossible this exercise is. How do you rank “Big Poppa” above or below the Stay With Me Remix of “One More Chance”? It depends: do you prefer “Happy Birthday” or “Auld Lang Syne”? In many ways, for as aggravating and subjective as any list can be, this is the most subjective.

Do me a favor and make a two- item grocery list, you’ll have an easier time deciding if “Milk” is better than “Eggs,” than we did deciding if “Who Shot Ya” is better than “Warning.” The variance on this list is staggering. Of course, every opinion is “right”, but it’s perhaps never been more defensible than when trying to make qualitative assessments of Biggie music. He defies consensus and definition like no other artist ever has.

There’s a little joke I include for my own amusement in these lists whenever I ship them off to Jeff and Martin. I always include the word “Definitive” in the title of whatever bullshit I’m ranking. The idea is making fun of the list itself, of the concept that we can order people, or their art in any lasting and/or meaningful way. I didn’t include that word in this title because even facetiously, the idea that any one person or group of people can make sense of Biggie’s music in a decisive, coherent way is absurd and insulting.

This is not hyperbole, I truly believe for generations, people who love music will approach these 106 songs in awe, in disbelief that an autodidact who couldn’t rent a car on his own was responsible for it all. The meaning of this music, and Biggie’s impact on history, will continue to shift and change shape on the horizon as that horizon falls further and further behind us; but I feel secure that decades from now, it will still be very much on our minds and in our hearts.

A brief aside on methodology: For a track to make this list, Biggie had to be alive for the recording: nothing posthumous is included; vocal samples don’t count. The murky waters come when considering versions of verses that have variations appearing on unreleased tracks and freestyles; if there was enough significant change, or a multi verse freestyle had a mixture of verse that appeared elsewhere, but was also original content, we included it. We tried to strike a tone of generosity and judiciousness, so completist basement types can feel free to go hammer in the replies, and maybe someday we will update this with your irate “well actually”s. As for how these brave souls made their ranking, was it a question of overall quality of song, Big’s performance on it, what they ate for breakfast and how the song in question made them feel as a result, I can’t say. That is between them and their Gods.

The greatest artists and writers go beyond the artifice of their creations, creations like the character “Biggie Smalls,” a 70s baby who grew up in a Reaganomic nightmare on St. James Place in the 80s, who was taught nihilism and violence by a society that hated him and actively tried to kill him, until it succeeded. They lay themselves bare. For Biggie, moments like that “I’m sorry” simply exuded from him on his formal songs, in interviews, in skits, they bled through in the margins of the music he made. I love him for his brilliance, but it’s his resilient warmth, his humor, the soul he left for us to revisit when we miss him everyday, but particularly on days like today, that elevates him beyond the base comparisons we fall prey to when doing the yeoman’s work of hopelessly attempting to order perfection.

There’s this selfish thing we do when artists die, we essentially grieve two deaths, the death of the person, and the death of the art we’ll never get to experience. Most of these artists are strangers to us, and while we pay lip service to the death of the person, it’s the death of the art that we truly mourn. For me, even as a 12 year old floored by the news of his senseless murder, Biggie was the rare artist whose loss as a person hurt me as much, if not more, than unmade art we all lost forever on March 9th, 1997. It’s a loss I suffer anew every time the ghostly track fades out into eternity on his final proper song, “You’re Nobody (Til Somebody Kills You)”.

But the statement made in that song title has never been less true of any great artist in my lifetime. Agree with this list or disagree (even I have my bones to pick), but understand we all embarked on this quixotic mission so today, perhaps, in our small corner of internet rap discourse, we can definitively close the book and say in unison, Rest In Peace Christopher George Latore Wallace, the greatest rapper who ever lived. — Abe Beame

Note to Reader: #106-50 are written by Abe Beame

*104-106. *R. Kelly- “(You To Be) Be Happy” & “Fuck You Tonight” & *Michael Jackson – “This Time Around“

Unfortunately, we have to open this list with three asterisks; we are running out of art in the world that has aged well, and not even Biggie is immune to the ravages of time. None of these songs “belong” as Biggie’s worst songs. “Fuck You Tonight” in particular, is an exemplary Rap and Bullshit ’90s classic that serves as another article of Biggie’s mastery of form on his kaleidoscopic, genre warping sophomore mission statement, Life After Death.

But in light of the allegations against Michael Jackson, and R. Kelly being a fucking monster, something we all came around to far too late (including after Big’s disciple Jay Z, made two joint albums with him) we could neither properly rank these songs in good conscience, or ignore their existence while staying true to the nature of this exercise. Perhaps a cop out, both in including and effectively excluding these songs from the list depending on your perspective, but this was the consensus.

103. Lil Kim – “Fuck You”

Grim and dour shit talk at the end of Hard Core on a Junior Mafia reunion, this song qualifies for the list by the slimmest of margins. Big gets on the mic for 4 lines of shit talk in between the second and third verse, but still has enough time to drop the “F” word. It’s here because we are refusing to subject ourselves to the replies that will follow when someone catches this and thinks we missed it. It’s here.

102. “Blazing Chronic“

This might be the slightest contribution to this entire list, even though it’s two half/quarter verses. It’s probably the only song here that feels under considered, potentially even mailed in. It’s difficult to assess whether this was even intended to be a song. It can be found on a Youtube video with Biggie’s “demos” but couldn’t have been a part of the original four track demo tape that got picked up by Matty C in The Source. If anything, it sounds later, closer to the Ready to Die rollout because the audio quality is decidedly better than the demo era tracks, and yet it’s worse than all of those. A confounding document.

101. Lil Kim – “Take it!”

An Interlude in which Cease and Big exchange a crass and horny locker room talk. It’s pretty raunchy and misogynistic, but nothing so bad it would preclude 63 million people from voting for you to be president.

100. Bandit – “All Men Are Dogs (9 MCs mix)“

An impressive array of mid tier tri-state guys got together for a misogynistic romp, including Grand Daddy I.U., Mackwell, Positive K, Pudgee Tha Phat Bastard, Raggedy Man, and Snagglepuss. Biggie gets the penultimate verse, just before his friend Grand Puba. This verse has been lifted several times, it notably contains the hilarious assertion that Biggie is, in fact, the father of the son of God.

99. Luke – “Bust a Nut“

This is absolutely filthy, a particular brand of explicit and very horny rap that X rated MCs like Uncle Luke and Akinyele built careers on in the 90s. As always, Big can rise to any occasion and assume any form, spitting graphic pornography that would make the God Larry Flynt blush.

98. Toni Braxton – “How Many Ways (Bad Boy Remix)“

This is the worst of Biggie’s R&B remix work, which is to say it’s better than 99% of R&B remixes. It has the feel of one of those industry moves Biggie would often kvetch over Puff dragging him to do early in his career (the song dropped in 1994) in the interest of broadening his fanbase. But Biggie is buried three and a half minutes in and follows a lazily spit early Puff semi-verse, and Big’s verse is even shorter.

97. Aaron Hall – “Why You Tryin to Play Me“

This verse was repurposed on the abominable “The Ultimate Rush” with Missy Elliot on Duets as well as the equally abominable “The Reason” off Faith Evans’ The King & I. Aaron Hall was a member of Guy, Teddy Riley’s foundational new jack swing act, who were signed to Uptown. As we’ll continue to see going through the bottom half of this list, Uptown connections explain a lot of the early random collaborations (mostly unreleased) Big would end up contributing to. That’s likely the explanation here, but while most everything Biggie ever touched left a digital paper trail, this song has what might possibly be the smallest digital footprint.

96. “Mumbling & Whispering“

Wrestling with Biggie freestyles is always tricky. Because he never wrote, everything he spit was in a sense spontaneous, and perhaps lent some of the magic to his performances on mic. But most of his verses, from the unwritten one take album verses to radio freestyles, were composed, complicated and fully formed when he delivered them, and would re record in other spots verbatim. This loose, rambling and shaggy “song” recorded in Mister Cee’s basement feels like an exception. It’s still very good, but lacks the laser focus and polish most of Biggie’s verses possess, going as far back as the original 50 Grand demo tape.

95. “Life After Death Intro“

Sneakily one of the most disturbing tracks in Biggie’s catalogue. Life After Death picks up right where Ready to Die left off, with a gunshot and a thud. In the opening moments of the sequel, Puff wrestles with grief at Biggie’s bedside in the hospital as he fights for his life. Further up this list, we’ll discuss how important intros and themes were to the world of Biggie’s albums. This intro transcended the world of the album and captured what must have been close to a real life moment, mirroring Puff at Biggie’s bedside as he fought for his life and just a few weeks before this album dropped. 24 years later, it’s still a tough sit.

94. 2Pac – “Runnin From Da Police“

This was recorded sometime around 93-94, with the intention of landing on Pac’s Thug Life compilation, then Me Against the World, which never happened for obvious reasons. But over the Easy Mo Bee beat, Big shares his verse with the also deceased Stretch (who has been subsequently accused of being the mastermind of the Quad Studio robbery/shooting in 1994 that led to the Biggie and Pac beef); the sound quality is poor, in spite of being one of only three collaborations on record between the two legends, there’s a lot working against it.

93. “Money, Hoes & Clothes” (Also known as “If I Should Die Before I Wake,” Unfinished, unreleased version)

Like any full or even partial Biggie verse, this sketch intended for Ready to Die then abandoned made the rounds, showing up on mixtaple/blend God Ron G’s “Stop The Breaks”, a pasted together motley posse cut with Raekwon, Killa Sin, KRS One, and O.C. It next showed up on Born Again, with the song more or less intact, with Beanie Sigel, Black Rob, and Ice Cube verses attached. The original feels very loose and improvised, in need of some tightening, but even this still has a routinely perfect opener and a thematic thread (the crib littered with guns).

92. “N***as*“

This unreleased cut would eventually be mined by 50 Cent for a hit off the Bad Boys II soundtrack. There are pieces of bars that will re-emerge polished on Ready to Die, but what’s impressive is even this rough outtake could be repurposed as a monster years after Biggie’s death with the Aftermath machine behind it.

91. “Ready To Die Intro“

We may or may not give Big, Puff, and the Bad Boy braintrust enough credit for introducing a cinematic quality to the rap album. De La Soul innovated the skit, Rza and Wu-Tang had similar themes, sounds, and moods, but let’s say if both groups had a director whose aesthetic they channeled, it was Kenneth Anger. The worlds of their albums were chaotic postmodern composites that threw everything at the wall, and they all stuck to create a shaggy aesthetic.

Bad Boy, particularly on Biggie’s projects, took specific and cohesive cues from 70s blaxploitation biographies of kids growing up poor, and of course, Scorsese and De Palma crime flicks about the resilient rise to power. Ready To Die’s table setter has all these qualities. There’s real production value on display: voice work, a soundtrack, the introduction of a story being told about a ruthless and sadistic character named Biggie Smalls that will unfurl over the course of the next 17 tracks. It is, in and of itself, a great and innovative piece of performance art.

90. Junior M.A.F.I.A. – “White Chalk Pt. 2” (Guide Vocals)

It’s tricky to quantify exactly how much of the material produced by Biggie’s affiliates can be attributed to him. There’s the suggestion that he wrote the majority of Hardcore, but how much exactly? And then there are reference tracks like this one floating around that give us pretty definitive evidence he not only wrote entire tracks for Junior Mafia, but laid down vocals for them to trace his delivery. It’s fascinating to listen to this back to back with Trife’s actual verse from this Mafia loosie off the Original Gangstas (A 96 Blaxploitation reunion) soundtrack. Trife hits all his marks, and is saying the same words verbatim, but it lacks Biggie’s spark. The man just had magic.

89. “Fuck Me (Interlude)”

We discussed this in depth in the intro. It’s Big at his self-deprecating best, it’s a great vocal and athletic performance by Kim, it’s a classic game of dozens, it’s quite possibly the funniest moment on Ready to Die.

88. Various Artists – “The Points”

This posse cut off 1995’s Panther soundtrack got an actual video treatment. Big gets the leadoff spot, and it’s always an excellent call letting the guy with the best verse intros in rap history spark a song, but it also probably didn’t hurt that the song was produced by his real life friend Easy Mo Bee. Ostensibly, this track is a symbol of unity featuring MCs from all over the country, but in execution it’s a kind of hilariously scattered and topic-less mess [ed. note. this song should be way higher]. Biggie wins best in show because of course he does.

87. Red Hot Lover Tone – “4 My N*****“

Today I learned this is actually Tone, as in Tone and Poke, as in the Trackmasters. Tone would play a quietly important role in Biggie’s career, producing “Juicy”, as well as the Trackmasters’ uncredited production on the Stay With Me remix of “One More Chance” and “Who Shot Ya.” This dropped just months after Ready to Die, and was presumably Big returning the favor for Tone’s invaluable contributions to the project. Biggie’s tongue twisting wordplay on this brief verse is phenomenal, and Nas would borrow a snippet for the hook on “Last Real N**** Alive” off God’s Son. There’s also an excellent Buckwild remix of this that’s a must listen.

86. Pepsi Freestyle

I’m such a sucker for great rappers spitting commercials. Shoes, 40s, cell phone plans, play it three times an hour on Hot 97 and take my money. I don’t even drink soda, and preferred Coke back when I did, but I may just run to a bodega and grab a Pepsi right now. This was something Big recorded in 1997 with DJ Enuff that was dragged out to commemorate Big’s Rock & Roll Hall of Fame induction last year. And, you know, to sell Pepsi.

85. St. Ides Commercial

Everything we said about the Pepsi Freestyle but with alcohol, so, you know, better. What’s great is this commercial from 95 also uses a line that creeps into the Pepsi freestyle, that he prefers both St. Ides and Pepsi to the “Tastes Great, Less Filling,” which was Miller Light’s slogan. So in a malt liquor commercial, and in a soda commercial he recorded two years later, Big stayed lacing sublimals in his rhymes, and Miller Lite hilariously stayed catching strays.

84. “House of Pain”

This is nearly as close as this list comes to a “bad” song. It sounds like something recorded in a shower booth, but the Stretch and Pac verses come off like first-draft, generic, one-take disasters (It was initially intended for Ready to Die, but responsibly cut, presumably because it’s bad and wouldn’t have fit at all). Then the clouds part and Biggie starts spitting, and it’s just remarkable. This seems like something tossed off in a dicking around blunt and 40 studio session for everyone else, but he simply had no other speed. It’s why he’s the greatest. He had no autopilot. Biggie plays with tempo and cadence, and the verse has the air of the jaded sadness he brought to his greatest and grief filled songs.

83. Pudgee tha Phat Bastard – “Think Big“

Big and Pudgee, a Bronx born rapper who ended up making a career for himself as a ghostwriter, went way back (they had previously gotten on Bandit’s “All Men Are Dogs” together). Circa Summer 93, Pudgee was considering whether or not to get on a beat provided by fellow Bronx native and Money Boss Player member Minnesota, featuring a hook from MBP’s Lord Tariq. The beat sampled Donny Hathaway’s “Vegetable Wagon”, which had just been flipped completely differently by Dr. Dre on “Rat-Tat-Tat-Tat.”

Perhaps as a result, Pudgee wasn’t feeling it and was about to pass. At that moment, Big walked into their room at Giant studios. The Tariq hook was pre-recorded and the song’s name, ironically, was already “Think Big”. Biggie loved it and immediately locked in, employing the mystical process of standing in front of a mic and nodding with his eyes closed for a while, something akin to meditation, as he thought through his verse, and knocked out his part in ten minutes. Pudgee quickly changed his mind, and the result is classic subway rattler, a cutting room floor ’80s cop show theme. Biggie goes in, a mix of hard spit and straight faced humor (“N***** is ass out like fat bitches in bikinis”)……… that got lost in the shuffle because they couldn’t clear the sample.

82. “Love No Hoe“

Circa 1991, the teenaged Biggie recorded a four track demo that eventually grabbed the attention of Matty C (Matteo Capoluongo) at The Source and launched Big to stardom. Other tracks on the demo are better known for good reason: they show the ferocity, the dexterity, the alien refinement, as the very first Christopher Wallace rhymes are being recorded. But this is probably the most endearing. If you can get past what was pretty standard tongue in cheek early 90s casual misogyny, which shouldn’t necessarily be excused but perhaps at least understood as rap’s predominant lingua franca unless you were the leather necklace type (Big decidedly was not), Biggie is actually warm and open hearted here.

Seemingly born with that booming voice and masterful delivery, Biggie never sounded younger. He’s the classic precocious New York City scammer that has a worldly confidence despite barely ever traversing outside his borough, who can feed you bullshit, and you know it’s bullshit, and he knows you know it’s bullshit, but through sheer charm and charisma you end up kind of taking the bait anyways. Here, it’s Big trying out his loverman shtick (all feather ruffling Bed Stuy braggadocio you’re supposed to take with a grain of salt), and again, he’s already impossibly close to what will be his “finished form” on his albums in terms of flow, control, and his master storyteller’s eye for detail (his girl buggin because his lips are chapped, indicating cheating somehow(?), gets me everytime), but more than “Microphone Murderer” or “Guaranteed Raw”, the goofy teenager he was shines through here.

81. R.A. the Rugged Man – “Cunt Renaissance“

Tone from Trackmasters was the plug on this one. Tone met RA at Chung King around ’93 before Biggie had really blown up, but by the time they got in the studio to record this, he had. RA’s label was hoping he could replicate the crossover success Biggie had found with “Juicy”, and urged RA to use his Biggie spot to do just that, and RA responded in typical fashion, by delivering the musical equivalent of raw sewage. This is just an absolute grimy, stinking, scratch bombed, underlit dive bar bathroom of a song. It’s evidence that if he wanted, Big could’ve also run in underground circles and given horror-core pervert maniacs like Necro a run for their money. Also, we can listen to this now and be thankful Crustified Dibbs made the decision to change his moniker to R.A. the Rugged Man.

80. Various Artists – “Flip Dat Shit“

A Biggie verse perhaps better known as the “16 Bar Acapella” freestyle, this posse track with Onyx, Naughty by Nature, and 3rd Eye was supposed to make the Who’s the Man the man soundtrack but didn’t, and wasn’t discovered until much later on a discarded advanced copy. Biggie is practicing classic New York mixtape flow here, hitting references and connecting on punchlines “Like Riddick Bowe.” Other than the fact this soundtrack already featured Biggie’s first great single, “Party & Bullshit,” it’s hard to understand why this didn’t make the cut.

79. “Can I Get Witcha?”

This was recycled for Born Again, but the original version over a prominent “Apache” sample is far superior. I like this song because there’s a popular narrative that much of Biggie’s commercial acumen was grown by Puff, that Biggie was a reluctant, exclusively hardcore MC who had to be led to pop. This is an instance of Big, early in his career, doing a more formal and pop leaning version of a song like “Love No Hoe”, presumably before he got involved with Puff, and it’s great.

78. Heavy D & The Boys -“A Buncha N*****“

A perfect posse cut from 1992 that has its fingerprints on a few subsequent Big tracks during this early 90s run. It was Big’s first major label appearance, and the first of several collaborations with Uptown artists Puff connected him to. Big loved Hev and even had considered a potential joint album. It was also the first, but not last time he collaborated with his high school classmate Busta Rhymes, who was making his first appearance here as a solo artist. And finally 3rd Eye (Jesse Williams III), the rapper producer who is featured on this song in both capacities, would also pop up on the track or in the credits on “Dolly My Baby” (remix), “Flip Dat Shit”, “Biggie Got the Hype Shit”, and the infamous 2pac collab “House of Pain.” It’s beating a dead horse, I know, but it’s simply incredible how comfortably Biggie holds his own on a track, his first as a signed artist, with legendary MCs he looked up to like Heavy D and Guru, who had years of experience on him.

77. Neneh Cherry – “Buddy X (Falcon & Fabian Remix)“

A song about Lenny Kravitz cheating on Swedish singer Neneh Cherry’s friend, and his wife at the time, Lisa Bonet. This deserves mention with the best Big R&B guest verses because he is just destroying the pocket here in full new jack swing. He does something great that a lot of 90s R&B songs did where he picks up the narrative of the song and takes makes the opposing argument, voicing the defamed, cheating “Buddy X”, and you’d imagine at some point in an argument, as their marriage was dissolving, Lenny said something to Lisa along the lines of, “The sex was great, but the headaches I can’t take/I think I made a very big mistake.”

76. Da Brat – “Da B Side“

In 1996, Big and Puff were ahead of the curve, jumping on this Brat remix with Jermaine Dupri when there was very little interaction between New York and the South. It was Bad Boy campaigning for pan rap unity at a time it was sorely needed with the East-West wars raging. Dupri would return the favor, working with Kim the same year on “Not Tonight” towards the end of Hardcore (The song is run of the mill mid 90s Dupri butter soft R&B tinged rap, but notable because the next year it was remixed as “Ladies Night (Not Tonight)” an all-star female MC showcase featured on the Nothing to Lose soundtrack).

There had been other New York/Southern collabs leading up to this (Including UGK, Keith Murray and Lord Jamar’s excellent “Live Wires Connect” on the Don’t Be A Menace soundtrack) but this was one of the most splashy for its moment. In the next few years, Raekwon would jump on Aquemini, and Jay-Z would be collaborating with Juvenile, UGK, and Dupri himself, but you could argue Bad Boy opened the door for that cross pollination. Oh, and by the way, the song itself is great. Big is firmly in the smooth/confident “Big Poppa” flow he used for commercial grabs like this, but takes nothing off his fastball. The structure is unusual for a radio hit, with Brat and Big trading bars rather than clearing out so each can deliver a proper verse.

75. Junior M.A.F.I.A. – “Oh My Lord”

For many, this is the forgotten Big appearance on Junior Mafia’s Conspiracy — as compared to “the hits” (“Get Money”, “Player’s Anthem”, and the “Gettin Money” Remix). It’s so obscure, both of Biggie’s verses make up sections of the infamous Tim Westwood Freestyle re-released on the 20th anniversary of his passing, and many believed their portions to be legitimate freestyled/unreleased material mixed in with verses from “The Points”, “You’re Nobody (Til Somebody Kills You)”, and “Kick In The Door”. Which is a shame, because it’s a great song that features a great, icy Special Ed beat and two great Biggie verses. Who knows who wrote Kleptomaniac’s verse, but who cares? It’s probably the best non Kim or Cease Mafia performance on the album. And literally every Biggie bar here is a quotable.

74. “Interview/Biggie Speaks”

A bonus track attached to “I Got a Story to Tell” at the end of Disc 1 of Life After Death, this 11 and a half minute conversation is a heartbreaking look at where Biggie’s head was in the lead up to the album. He sounds alternately hungry, disillusioned, disappointed, and hopeful. You can’t pick up the interviewer’s audio (or it’s edited out) so it sounds like Big having a conversation with himself, wrestling with the drama he believed he was finally putting past him, and what must have been enormous pressure to top the perfection of his debut. He talks process and approach to the album, what he saw as his role as an artist, and reflects on the legacy and impact of his beef with Pac. But more than anything else, what he communicates, as always, whether in verse or conversation, is his intelligence, his empathy, his wit, his confidence, his humor, and his warmth.

73. “Whatchu Want“

An Easy Mo Bee production that was cut from Ready to Die after being deemed “Too Hardcore” for the album. As impossible as that standard seems, when you listen to the song now, you kind of get it. Maybe not that the song itself was “Too Hardcore” in terms of its content in comparison with the multitude of wild shit Biggie spits on his debut, but perhaps its inclusion alongside the rest of the incredibly blue, rough material could throw off the album’s perfect calibration, balancing hardcore and pop. This is because the song is a ruthless Howitzer cannon, and Biggie is in full, breathless “sadistic/savage” mode. In other words, perfect.

The epic drama of “Get Money” is remixed as a pleasant money counting session with the Mafia’s brightest stars. Lance “Un” Rivera and DJ Enuff’s take on the often sampled “Don’t Look Any Further” is one of the best iterations, I particularly love how much of Dennis Edwards’ vocals are left in the margins. All three performances are great. To this day, it’s a fucking jam.

72. “Playa Hater”

I was listening to this randomly a few months ago when it occurred to me that this is Biggie’s idea of a Naked Gun/Bond theme. It’s lush, orchestral, melodramatic, and hilarious. According to Cease, they were all stoned in the studio fucking around when they made this, which makes a lot of sense. It appropriately contains elements of “Basketball Jones” by Cheech and Chong, and “Hey! Love” by the Delfonics. It’s a glittering 70s soul ballad that got an assist from Ron Grant, who has hosted a long running open mic at the Village Underground in Greenwich Village. The track was recorded at Daddy’s House in Hell’s Kitchen, which just happened to be next to a strip club named Blue Angel where Ron’s Band was rehearsing. They were grabbed on a whim and brought up to lay the track down, which they did in one take.

As we learned in Emmet Malloy’s recent (excellent) Netflix documentary, Big could really sing, so the warbling on display here feels intentional, an in-joke laughing at the very idea of a sweeping ballad in the middle of Life After Death. Even though it’s an insane, howling, stoned concept song that easily could’ve been cut from the album, it makes a kind of sense as a mood piece alongside mature gangster epics like “Fuck You Tonight”, “The World Is Filled”, “Another”, and “I Love The Dough”, among others. Whenever I listen to it, I feel like I’m in a penthouse hotel room with floor to ceiling windows, wearing a linen suit and Gucci shades at night, holding a flute of Perrier Jouet Belle Epoque, looking out on the city glittering below me. This was surprisingly a Hot 97 mainstay in New York for a few years following Biggie’s death.

71. Tracy Lee – “Keep Your Hands High”

You probably had this album if you were in high school in the late 90s, not for this track, but “The Theme,” which was a throwback party anthem and a major hit in 1997, when Tracey Lee’s debut Many Facez dropped. The album was produced by go to Bad Boy Bomb Squad the Hitmen, which perhaps explains why Biggie recorded this verse for Tracy at D&D in December 1996. This means besides his contribution to “Victory,” recorded the day before he died, “Keep Your Hands High” was probably Big’s penultimate recorded performance, and it’s a great one. Biggie always gave more of himself to these one on one collaborations than any other artist. It’s never that he just shows up, drops a verse and cashes the check, there’s always these unexpected little verse snippets, trading bars with the artist, adding ad libs, going above and beyond what any other rapper was doing with their features.

This sounds like a progression from what he was doing only a few months earlier as he wrapped up Life After Death. The punchlines are crisp and sharp as ever, but the wordplay is increasingly dense, the rhymes and allusions becoming more complex. Stumbling upon this on a first listen (the album dropped two weeks after Big died), was like seeing the final, anti-climatic, low budget performance from a dead actor trickle out after they pass. It’s weird, and kind of sad to think, this is it.

69. “Macs & Dons”

Even before he blew up, Biggie was writing and rapping for others, as this is a reference track for an MC named Shelton D, recorded at Gordy Groove studio in 1994. This one is extremely light and fun, perhaps because it’s modeled for another rapper, a lot of Biggie’s trademark menace is absent. It’s absolutely packed with reference and in-jokes as Biggie bops and swings over Fresh Gordon’s very early 90s production.

68. “Another”

Not a psychologist, but perhaps there’s something to glean from Biggie and Kim’s two full scale collaborations being War of the Roses style he said/she said breakup anthems where murder, jail, or at the very least ghosting forever is very much on the table. By all accounts, Big and Kim had a wildly tumultuous and dysfunctional relationship that lasted much of Big’s adult life, and again, should you be so inclined, there’s a lot of psychology on display both here, and on “Get Money” (Kim has alleged most of the content of this song was derived from an actual argument the two had in the studio that resulted in violence).

More so than the life or death stakes of “Get Money,” “Another” seems to exist in a world closer to this one, albeit one that’s still highly stylized and filtered through a vaseline smeared Scorsese lens. It feels like a kind of cathartic couples therapy session built on both Kim and Big reckoning with the “Can’t live with em” platitude, the conflict between the attraction and repulsion that can come with a volatile relationship gone on too long that both Big and Kim are working through in verse. Kim is absolutely ferocious, and holds her own, remaining Biggie’s all-time greatest sparring partner, give or take a Jay-Z. It’s riveting stuff, which occasionally may obscure how great the actual song is.

67. Mary J. Blige – “What’s the 411? (Remix)”

A tough call because Biggie is only spitting the first verse of the forthcoming “Dreams,” but we decided to allow it because “Dreams” has two additional verses, this is an original song as well as the first time Biggie spits the verse, and it’s a fucking classic.

66. Funkmaster Flex – “Freestyle #13”

There’s a chance Funkmaster Flex’s 60 Minutes of Funk Vol. II is the greatest officially released rap compilation ever produced, including the slew of great rap soundtracks we saw in the late 90s. This track is one of the many reasons why, the musical equivalent of one of those Timbs, North Face and Yankee fitted New York centric memes. The Lox brought something out of Big, the competitive nature of a champion sparked by young challengers, like when an established star squares up with an up and coming young talent the media is comparing to him. We didn’t get enough collabs between the four men, but every time it happened, Big put on a show.

65. Busta Rhymes – The Ugliest (Or “Modern Day Gangstas”?)

As mentioned before, Biggie and Busta went to high school together at George Westinghouse Career Technical High School in downtown Brooklyn, but you get the impression that in spite of a bit of overlap, they were not the best of friends (By his own account, Busta had no idea Biggie rapped when they were in school together, and Neneh Cherry said as much, recounting a story when the two ran into each other while Big was recording his verse for “Buddy X,” that Biggie said he didn’t fuck with Busta). But the two collaborated fairly regularly throughout Big’s career. This exemplary early Dilla beat was probably their best moment together, a track slated for Busta’s solo debut, The Coming, that was cut because they picked up on the Pac not so sublimals in Big’s verse and Busta didn’t want to get involved: “And the winner is, not that thinner kid/Bandanas, tattoos”. As a result, it took a while for us to hear this in its intended form, finding bullshit second life on posthumous cut and paste jobs.

64. Lil Kim – “Crush On You”

“Crush On You” is one of the more difficult songs to properly rank in Big’s catalogue. Mase was famously paid 30 racks to write five songs for Lil Cease. He broke 5K off for his friend and Children of the Corn group member Cam’ron, who promptly wrote “Crush On You,” an instant classic and major hit at the time. But the details are lacking. Does this mean he wrote Biggie’s hook for him? If he did, does that take away from its perfect and inescapable delivery? Can we imagine the hit landing as hard if Kim, or Cease, or Cam himself delivered it?

It’s a fantastic song for many reasons, one of which is Cease’s great, ghostwritten verses, the Jeff Lorber sample, the remix that Kim improves on, and Biggie’s hook. It would be great if a journalist with more access than we have could go back and do an autopsy of Hardcore and Junior Mafia’s Conspiracy. How much of the content exactly was Biggie responsible for? For now, we’ll leave it here, Cam’s incredible pen plus great performances from Cease, Kim, and Big.

63. DJ Eddie F – “Let’s Get it On”

This appearance really displays the duality of Pac. On “House of Pain” he’s at his listless, cliche spouting worst, but here he’s electric. His wise beyond his years dismay rhymes with Biggie on the rare occasions he deigned to explicitly address social issues. Here, Pac is swinging all over the place, entrenched in pocket. In comparison, Biggie’s verse is fun and frivolous. By my count, this is the one time (1-4 if you include the MSG freestyle) Pac bested his friend and enemy.

62. Funkmaster Flex – “Wickedest Freestyle”

Another Big loosie that eventually landed in Funkmaster Flex’s lap for one of his studio album “Mixtapes,” this masterful verse was originally recorded for Mister Cee. Biggie turns the moment into an event, having a ball playing a Carson/Hope-ish master of ceremony on the intro over “Ellie’s Love Theme” by Issaac Hayes, before the instrumental (rendered sinister by Big here) for Casual’s “I Didn’t Mean To” drops. A lot of Biggie’s threats and shit talk haven’t aged well. He frequently employed sadism, torture, and even the occult as he would warn off would-be competition. We’ve gone through two revolutions in speech, both in rap and society, since Big passed.

First there was the hyper-masculinity brought on by Cam and Dipset, basically catching your friends or foes in moments of unintentional innuendo-laden phrasing, and dunking on them for it, and then the enlightenment of being sensitive to sexuality, gender, and sexual trauma, among other words, phrases and lyrics some might find offensive or triggering. You will find none of either consciousnesses in this verse (along with much of Biggie’s raw lyricism), written and performed sometime during the Ready to Die rollout in the early 90s. It’s vile, Biggie at his psychopathic and imaginative worst. There’s a secondary conversation worth having about why Biggie’s language was so extreme and oriented towards shocking and disturbing the listener. The entire approach Christopher Wallace brought to Biggie Smalls was as a mirror held up to society. His intention was to create a character that was fundamentally broken, violent, without compass and willing to do anything to anyone at any time. When you listen to songs like “Everyday Struggle,” or “Things Done Changed,” he’s explaining the conditions that create a Biggie Smalls.

But on verses like these he was the chilling outcome. As a writer and a genius, was it fun for Big to write for this lost soul who was “crazy and deranged”, constantly dreaming up novel ways to communicate his evilness and alienation? Probably. Was it something he would’ve eventually grown out of? Also probably. Does much of this come across without a macro consideration of his entire body of work when you listen to fun little heaters like “The Wickedest Freestyle”? Probably not.

61. “Enuff Freestyle (Guaranteed Raw)”

I can’t imagine what it must have been like being in a cafeteria with Big at Bishop Loughlin high school in the late 80s, pounding a beat out on the table for him to rip. Or maybe I can, because that’s exactly what “Guaranteed Raw” feels like. The track contains the battle verse Biggie kicked in front of that bodega on Bedford and Quincy against William Tory “Supreme” McClune, which is why it isn’t included in this list.

60. Supercat – “Dolly My Baby (Remix)”

An absolute guest stunner from Big. He was Jamaican, and had his dalliances with his roots both here, and on “Respect”, a genre of crossover track that was common amongst Brooklyn MCs in the 90s. The rest of the song is mostly vibes. Supercat kills it, but 3rd Eye and Puff decidedly do not. Biggie’s eight bars are devastating, quickly showing up to drop, “Lyrical lyricist kicking lyrics out my larynx.” an incredible work of alliteration from a guy who didn’t write his verses, and arguably one of his greatest single bars of all time.

59. “Biggie Got the Hype Shit”

Right up there with “Unbelievable”, or “Machine Gun Funk,” or “Kick in the Door.” Just a ferocious lyrical barrage. This was from a very early recording session with Puff, who I imagine sitting in a cushy leather chair on casters, staring dumbfounded through the studio glass, into the booth like Daniel Plainview at the Little Boston field, watching a geyser spraying oil into the night. The master for this track was lost in a fire that destroyed the Bronx studio where it was recorded, which is why it never saw a proper release, but this rough cut surfaced years ago.

58. “Miss U”

A heartbreaking dedication to a friend named “O” (Olie, or Roland Young) Big lost in a murder that gained particular relevance in the wake of his own tragedy. I can’t find the quote, but somewhere in my obsessive research leading up to this piece, I found some reporting that alleges we can actually hear O doing hook work on an early Biggie Demo. Biggie was often cavalier about death, both in his hyperbolic and heightened threats, as well as his own vocal acceptance of it in what he had predicted over and over would be a short and violent life. “Miss U” is one of the only times he allowed himself to soberly contend with the pain and grief that comes with loss, and he’s poetic and insightful, allowing a rare window of vulnerability into how much the loss of O hurt him and the people who cared about O. Perhaps this is why it was the instrumental that played as mourners approached Biggie’s open casket after Volleta Wallace read scripture, Puff delivered a eulogy, and Faith sang gospel at Frank E. Campbell Funeral Home, just off Museum Mile on the Upper East Side.

57. “Microphone Murderer”

When people talk about Biggie’s preternatural polish and confidence as an MC, they’re probably referring to this. The whole demo tape is great, but there’s something about this sprawling verse, where he’s both channeling and besting his favorite rapper, Big Daddy Kane, on his own shit. It’s like Biggie’s Game 5 of the 2007 Eastern Conference Finals (I personally lose my mind when he runs through all the Jacksons, a little aside/device that would be sophisticated today). Most of the verse was later rerecorded for the “Another Rough One” freestyle, but this is the one. It’s the voice, the command, the punchlines, it’s all there, already, at the age of 19 in 50 Grand’s basement. You could clean up these vocals and slot the verse in nearly anywhere on Life After Death five years later, and no one would know the difference.

56. Sadat X – “Come On”

Puff was from Westchester, as were a surprising number of rappers and producers that were integral to the New York scene in the 90s. Puff, Pete Rock, and Heavy D were from Mount Vernon. DMX and the Lox were from Yonkers. Brand Nubian was from New Rochelle. A lot of the early Big loosies can be explained by this Uptown Records/Westchester plug, including this, probably the best of the bunch.

We’ve included the original Lord Finesse version, a decidedly murky and grimier iteration that Puff steamrolled for the version that eventually saw the light of day on Born Again (which is still pretty murky and grimy itself and I don’t hate nearly as much as Sadat claims to). If you’re wondering why the infamous “MSG Freestyle” at the Budweiser Superfest with Scoob Lover and 2pac is not on this list, it’s because Biggie’s verse was featured on this song. This was recorded in 1993, and never saw a proper release because according to Sadat, it was Puff’s punishment for him capitalizing on a clerical error by Bad Boy and cashing two checks for the same session. Whichever version you prefer, it’s an electrifying, vintage performance by both Big and Sadat.

55. “Nasty Boy”

When you want to attempt to figure out how Biggie may have really felt about 2Pac, you know, deep down, consider he recorded this the night Pac was killed. I can’t imagine a song that dispassionately veers further from trying to grapple with the loss of a former friend whose made himself the bane of your existence than this sex romp.

From Biggie’s perspective, it’s interesting to compare this to the filth he recorded on early tracks like “Bust a Nut” with Luke, the posse cut “All Men Are Dogs”, or even the original “One More Chance”. Biggie was clever and captivating (and, you know, gross) on all of these, but often sophomoric. No one would call “Nasty Boy” a mature statement of purpose, but it’s comparatively evolved. It’s more narrative driven, the scenarios more imagined and colorfully sketched, featuring actual characters that go beyond blank canvases for Big to, uh, project onto (sorry). In other words, while much of his early sexual exploits were communicated in the abstract with punchlines, on “Nasty Boy” he commits to fleshed out Freaky Tales.

54. “You’ll See”

With all due respect to “Last Days,” the consensus choice, this is my favorite of the Lox and Biggie collabs. It was the introduction of the Lox as Bad Boy artists, the B side to Faith Evans’ “You Used to Love Me”, and most importantly, it’s the guys all running wild over the “You’re a Customer” instrumental. It’s a great contrast of style.

The Lox are all squarely in hungry Yonkers kids mixtape mode (A young Styles kicks off ceremonies and delivers the second best performance), but Biggie decides to bring “Big Poppa” energy, going long but staying above the fray with designer drops and beautiful women shit talk. Styles has described Biggie’s come out line, “N***** talkin’ it but ain’t livin it”, as a bit of shade directed towards the Lox, a way of saying, I have all the things you rap about aspirationally. A kind of putting the trio in place. “You’ll See” feels very much like a war room session with the wizened head of a family and his three overzealous shooters looking to make names for themselves, that he’s keeping on a leash.

53. “Friend of Mine”

In all things, Biggie projected confidence. There are few flows in the history of hip hop that were even on the same planet of assurance he was operating in, whether warbling off key on a piano bar ballad like “Player Haters” or going toe to toe with Jay-Z or Meth, so it would be easy to think of him as invulnerable. But Biggie was overweight, had a lazy eye, and working class most of his life. He talks about it occasionally, calling himself fat and ugly, telling stories about beating up kids who teased him for wearing bootleg Lacoste and Le Tigre gear, making offhand jokes about his wife cheating on him with 2Pac on “Brooklyn’s Finest.” It’s hard to know how he really felt about these things, but to me, it always had the flavor of classic Jewish self-deprecation, calling himself out before others could. We see some psychology on “Friend of Mine,” a parable about a woman who fucks Biggie’s better-looking friend (presumably Damien “D-Roc” Butler), resulting in him smutting her out.

The rough edges of the song are smoothed, we don’t get much in the way of vulnerability or hurt feelings, perhaps betrayal both by his girl and his friend, but you need to read inflection and subtext. It’s sadly in the glee he takes in his revenge as his career takes off and he’s empowered, returning his hurt, in the warble in his voice as he appraises his man D’s game, it’s in Easy Mo Bee’s hook, sampling Black Mamba’s “Vicious”: “You know that ain’t right, when they’re friends of mine”, it’s in his need to make the song at all, showing and telling us why he’s “earned” the right to be callous and cruel to women he hooks up with. It’s sneakily one of the clearest pictures we get of Biggie’s insecurities.

52. “Road to Riches” (Or “Real N*****,” or “West Coast Freestyle”)

This track was allegedly released as an album promo and finds Big rapping over “Deep Cover”, “Nothin But a G Thang”, “Black Superman,” “Murder was the Case,” and “Gin and Juice.” But really it’s a short story collection loosely held together by a great, Kool G Rap quoting hook. The first two verses are vaguely Goinesian, perhaps a touch of Puzo, but the third, featured on what ended up probably being Biggie’s best known posthumous hit “Notorious”, feels more like an indulgent horny comedy, Phillip Roth or Sam Lipsyte. Whatever your preference, because it has only been served up “properly” in bits and pieces, it doesn’t get credit for being one of Biggie’s best series of narratives, but it is.

51. Shaquille O’Neal – “You Can’t Stop the Reign”

Something Biggie fans like me wrestle with constantly is the crucial and incredibly consequential question: “Which Biggie is your favorite?” He had so many styles and personalities that he could float between. The purists will tell you it’s the ass whipping wunderkind of “Unbelievable”, perhaps the double timed stylist of “Notorious Thugs,” the grimy hater on “Gimme the Loot”, the shockingly tender and human poet of “Miss U” and “Juicy.” And then there was this persona, sort of birthed with songs like the Stay With Me remix of “One More Chance” and “Big Poppa,” but really a style that found its final form on Life After Death, and gorgeous tracks from that era like this collaboration with Shaq, a friend of Big’s he was on his way to see the night he was murdered in Los Angeles.

This song was the maturation of a project Puff spent the entire first half of his career developing: The integration of R&B and hip hop. While it started with R&B artists singing over rap records, it eventually mutated into a hybrid of rapper spitting over softer, R&B infused production. The period around Life After Death saw some very good iterations of this, off the top of my head, specifically much of LL Cool J’s Mr. Smith, and Heavy D’s Waterbed Hev. But of course Biggie was the best at it, and perhaps never better in this lane than he was here (Rick Ross for instance, can thank just this song for the whole second half of his career, when not in Luger Trap mode).

There’s just an intoxicating luxury to this song, it’s SO fucking smooth, both in his dulcet tone and the way the verses flow on a bed of cold pressed, unfiltered olive oil (The Chris Large smooth jazz, drawn butter drenched production gets an assist as well). Biggie isn’t just dropping name brands and bragging about his wealth and access, he found a way to make something that SOUNDS rich, it FEELS rich, like a brand new pair of lined Timbs or the weight and smell of a fresh leather. It’s a lobe of foie gras, a spoonful of caviar, a truffle supplement. Rappers still try to capture moments like this, to make opulence flesh like this does, but none can match it. For his many innovations, this textile approach to rap and bullshit may have been Biggie’s most influential and impactful, and yes, sometimes it’s my favorite. — Abe Beame

50. “Last Day”

“I did real songs with Big, no made up shits” is a perfect diss record bar in the sense that there’s no real rebuttal available. In fairness to 50, he was still learning the ropes from Jam Master Jay when this song was recorded, but rap battles aren’t about fairness. And when you have a card that good, you have to play it. This Life After Death cut is the crown jewel of said real songs, a posse cut that still makes me marvel in the present.

Every LOX member brings their A game to the festivities, as to be expected. The jarring part is when the man himself drops by at the end. A very good song takes a flying leap into greatness, as Big’s enemies are unable to sleep, too haunted by nightmares of his dominance. He jumps from two interwoven crime scenes that both beg for their own song length elaborations into the verse’s undeniable highlight: “make you a classic like my first LP”.

There’s something to be said for not waiting for anyone else to give you your flowers. Big wasn’t about to wait for someone to tell him what he already knew. Ready to Die was going down in the history books. The “Last Day” verse is a masterclass from an artist in full command of his craft. The LOX went on to make their own mark, but on this one, they were simply Jimmy Jump to Big’s Frank White. — Jeff Castilla

49. “Been Around the World”

There’s simply too much going on in Diddy’s “Been Around the World” to not revisit the craziness. For the Bad Boy founder’s debut studio album No Way Out, Diddy channeled David Bowie’s “Let’s Dance” for its third track and tapped Mase and Biggie to hold down feature duties. The music video singlehandedly recreated the opening to Face/Off, tapped Vivica A. Fox as a suburban house mom, featured Diddy on the toilet talking to Quincy Jones, found Wyclef Jean tapping phone calls and attempting to crash Diddy’s private jet and ended with some salsa dancing with Jennifer Lopez [Ed. Note: Patrick is somehow underselling this, do yourself a favor and watch if it’s been a while. It’s fucking insane Puffy at his most Bay/Fincher level preposterous].

It all somehow managed to work together beautifully. Biggie did the most with his brief albeit memorable posthumous feature, released just eight months after he passed, channeling Lisa Stansfield’s “All Around the World” for a half-sung, half-rapped chorus. As Bad Boy shifted into the label’s next phase, one that would rely heavily on Mase after B.I.G. ‘s death, “Been Around The World” found Biggie prepping No Way Out listeners for one last hurrah. His memorable features on “Young G’s,” “Victory” and “All About the Benjamins” were more substantial, but none were as experimental and greater than the sum of their parts as “Been Around the World.” Plus you left with The Madd Rapper and Madd Producer hating on Biggie’s “Hypnotize” video and incredulously remarking on the video having mermaids. — Patrick Johnson

48. “B.I.G. Interlude”

Some time between recording his famous demo tape and finishing Ready to Die, Christopher Wallace switched his official stage name from Biggie Smalls to The Notorious B.I.G., which he would stick with for the remainder of his life. But he never stopped accumulating nicknames. One of his favorites was “Frank White,” as in “the Black Frank White,” as in the Christopher Walken character from King of New York who was modeled in part on the Philadelphia rapper Schoolly D, a friend of director Abel Ferrara. Schoolly D, of course, had become famous back in ‘85 for “P.S.K. What Does It Mean?,” which was more or less gangsta rap’s Big Bang. (In today’s era of cops and prosecutors using rappers’ lyrics to incriminate them, “P.S.K.”’s coyness about gang initials holds up tauntingly well.)

The “B.I.G.” interlude, which flips the “P.S.K.” hook and treats Big’s vocals with the same mid-Reagan echo, is tucked between “What’s Beef?”––where Big chuckles that he’ll let his trembling enemies keep their jewelry, but Puff is stone-faced––and “Mo Money Mo Problems”––where Puff and Mase are relaxing on yachts while Big sneers at the DEA. Life After Death is a masterpiece, perhaps the only masterpiece, about the experience of being a rap star, and its dozens of disparate parts are held together by Big’s mastery of tone: sly when you think he’s being obvious, winking when you think it’s a threat. What better way to underscore this than to spell his name while alluding to a record famous for obscuring its true topic? “What?” he cracks at the song’s end. “It ain’t no more to it.” — Paul Thompson

47. Total – “Can’t You See”

There are few greater demands than asking for all the women within an 8,122 mile stretch, but the Notorious B.I.G. was not one for small orders. On Total’s ’95 “Can’t You See,” B.I.G. teamed up with the R&B trio and sent out a PSA to “all the chickenheads from Pasadena to Medina.”

While Total narrowed in on their one and only sweetheart, B.I.G. claimed a flock and then some, kicking off the sultry love song with a touch of sex, death, and a nod to his clique. Total, of course, eased right in with their first verse, and the Sean “Puffy” Combs-produced, James Brown-sampled track rolls right on. B.I.G. did his part, and now the girls got the last word.

This hip-hop and R&B alliance was less “men are from Mars, women are from Venus” and more of an example of how the two genres, genders, and expressions balance each other out. And no one knew this better than B.I.G. It was, after all, Total who sang the hook on “Juicy” and the group’s Pamela Long who swooned over Biggie Biggie Biggie’s words on “Hypnotize.”

This time, B.I.G. did the ladies a favor, lending his star power to the single on the Bad Boy trio’s debut self-titled LP. “Can’t You See” would peak on the Billboard Hot 100 at #13 and the Hot R&B/Hip Hop Songs chart at #3, and the Bad Boys and Bad Girls would see another ’95 win.

On “Can’t You See,” B.I.G. set the tone and dropped the mic. And in the end, what B.I.G. brought was balance: the confidence to know the song didn’t always need to be his and the cool to know that he’d always be what made the song. —Paley Martin

46. “The World Is Filled”

Biggie’s pimp rap song is the best posse cut he was ever part of. Yeah, I know “Flava In Ya Ear” Remix has That Verse, “Notorious Thugs” is mind-bending, “Mo Money Mo Problems” is perfect, but they all share something in common: Biggie steals the show. It’s like watching LeBron in his second Cavs stint — a lot of fun, a few nice complementary players, but you’re not really checking for Kevin Love.

“The World Is Filled” is, by my estimation, the only group song where Biggie doesn’t outshine the other rappers. That’s not a slight against him — his verse here is classic — but you have a surprisingly charged-up Puffy doing his absolute best Ma$e imitation, saying misogynistic things in the slickest way, and then there’s Too Short, taking to heart Carl Thomas’ delirious chorus about pimps and hoes and doing the verse he was born to do. He was 10 albums deep when they made this; he had his rap style down to a science.

It’s just an absurdly brilliant record. All the parts lock into place. Maybe it was the atmosphere in that session, as Too Short described it: women lounging around Puffy’s studio, weed smoke and booze smells clouding the air, everyone being noisy as hell, Puffy giddily showing everyone how good his verse was. It seemed like a fantasy; maybe it was just a hotbox. Whatever it was, Biggie emerged out of it with a verse committed to memory. The Remy was in the system. One take and he was finished. — Mano Sundaresan

45. “Queen Bitch (Guide Vocals)”

I had a debate on Twitter recently with a cabal of studied hip-hop nerds I both like and respect who took a shot at Biggie for his use of language. They went after a throw away line on Life After Death’s “What’s Beef?” in which Biggie claims his associate Gutter kidnaps kids, rapes them, and throws them off of bridges. I tried to make the case that literal readings of Biggie verses like this were reductive, an insult to his project and a misreading of his intention, which was interpreted in this instance as somehow bolstering his bona fides as a thug with wildly absurd and over the top menace like this.

Well folks, if you want to see how literally to take Biggie when he’s talking his shit, I couldn’t come up with a better counter than him referring to himself as a “bitch with that platinum grammar.” Maybe second only to Biggie Smalls himself, Lil Kim was Big’s greatest creation. She was a bottom chick who would shoot, fight, and fuck like a man (echoes of raw female blues protagonists like Bessie Smith), and would change the unapologetic, flaunted sexuality and proud gangsterism of female MCs forever. In Kim, with songs he clearly wrote and even performed guide vocals for like “Queen Bitch (a lyrical workout that stands shoulder to shoulder with his very best showcases), Christopher Wallace shows his talent as a writer and thinker, equally able to embody Biggie Smalls as he is that character’s gangster moll. He proves that if we’re to take his flights of fancy at their word, we’re diminishing his imagination and ability, and the joke is on us. — Abe Beame

44. “One More Chance”

Ready to Die is a snapshot of a creator and art form evolving by the hour. You can hear it in beats ranging from Easy Mo Bee’s late Golden Age funk to Preemo’s state-of-the-art boom-bap to Chucky Thompson’s R&B-inflected grooves presaging Bad Boy’s pop tendencies. You can hear it in Biggie’s youthful flow – higher-pitched and busy compared to the more poised, measured baritone delivery that would become his signature. And you can hear him trying on personas – whether it’s the neighbourhood dude turned local hero, the psychotic stick-up kid, the ice-cold criminal mastermind and perhaps most notably, the lady-killer.

In ’93, when the first album cuts were being laid down, sex rap was basically locker room talk. First-rate contemporaries Heavy D and Big Daddy Kane would fatally wound their own careers by making slow jams that prioritised seduction over fucking. But for Big, this was just another old-school shibboleth that he’d crush through the sheer force of his talent and charisma.

In a 1998 profile in Spin, writer Sia Michel describes Wallace as “a shy, warm-hearted, deadpan funny, dick-waving lost boy who made you want to hug him one minute and slap him silly the next.” Those qualities are everywhere apparent on “One More Chance.” If the smash remix saw Biggie play the irresistible silver-tongued mack over a club friendly groove, here he’s the priapic teenage pussy-hound, neck-deep in the perks that come with being a successful rapper, over a porno beat.

An answering machine message of his infant daughter telling “the hoes to stay off his dick” pretty much sets the tone. He’s totally jazzed on being a fat ugly sex magnet and if nothing else, he sets expectations up front. He’s obnoxious and lewd but witty enough to get away with it. The sexual politics are questionable but he’s the first male rapper I ever heard talk about giving head, although as the song’s most hilarious lines warn, you better know how to comport yourself when Big Poppa “goes down below.” If sex is in the mind, then lyrical intelligence is the ultimate aphrodisiac. — Joel Biswas

43. “Just Playin (Dreams)”

“Just Playing (Dreams)” is a concept track wherein Biggie namedrops every hot female R&B singer of the 90s before sharing whether he’d hit it or not, how, and why. Think about that for a second: this shit just wouldn’t fly in an era of instant reactions. Sure, Nicki Minaj can reclaim the concept (or bite Lil Kim’s version) under the cover of feminism, but she pulled more punches than a celebrity prize fight. Meanwhile, the original sees Biggie setting things off with a reference to Patti Labelle’s sexual assault, saying he’d give Tina Turner Ike flashbacks, and claiming he’d fuck RuPaul over Xscape. Good luck getting away with that post-Twitter, because to quote a completely different song: things done changed.

And yet “Just Playing (Dreams)” worked for reasons beyond the 90s being a bastion of shock-jock humor. For one, there’s obvious affection in Biggie’s voice, and underneath his authoritative baritone, you can almost hear this 21-year-old kid chuckling to himself under his breath. While Mariah Carey almost certainly didn’t appreciate being called scary, it hits different when the guy saying it called himself Black and ugly as ever, on his own hit single. The song may be childish, but it wasn’t intentionally cruel.

The other reason “Just Playing” works is because deep down, it’s a pretty nerdy song. Don’t forget, you couldn’t just Google a list of R&B singers in 1993, so the song was a hint that under Biggie’s tough guy exterior and King of New York image, he was drooling over the day’s superstar divas just like the rest of us, and paying attention to celebrity news while doing so. At the end of the day, that he got away with it shows just how much affection and good will there was for Biggie at the height of his powers, even when he was being kind of a dick. — Son Raw

42. Lil Kim – “Drugs”

Christopher Wallace was clearly larger than life. But if there’s one aspect that’s fallen through the cracks more than any other these last 20 years, it was his role as head coach. If you locked down studio time with him, he’d be sure to coax greatness out of his peers. And if he penned you a verse, you were guaranteed a classic track.

Lil Kim’s Hard Core was certified double platinum, sold 5 million copies, and cemented her path to becoming a Top 5 female MC. Female rappers like Lyte, Latifah, Rage and even Shante had already laid the foundation, but the Brooklyn Queen Bee kicked down the door.

Hardcore by name, Hardcore by nature, Lil Kim came with a sexual carnality that no one had ever seen before. She single-handedly raised the bar for raunchy lyrics in hip-hop by rapping rhymes like “You ain’t lickin’ this, you ain’t stickin’ this . . . I don’t want dick tonight/Eat my pussy right.”

Her blend of provocative sass had become a narcotic. Her bracing confidence made most male rappers quiver.

Kimberly Jones freestyled for B.I.G on a street corner and transfixed him on and off wax. Shortly thereafter, he recruited her to join Junior M.A.F.I.A.

On a contact high Biggie and Kim struck up a tumultuous love affair. He became her mentor, got to work as executive producer of Hardcore, and slid on a quartet of tracks himself. One of those being “Drugs.”

A wavy B.I.G. croons the hook, comparing Lil Kim’s potency to Sensimilla(a female marijuana plant) among other stimulants and confesses that touching her, and being immersed in her vibe is the ultimate rush. While Kim taunts, teases and pistol whips listeners rapping about jewels, fur, cash, liquor, sex and invitations to “lick her ass” coded in Arabic slang.

Backed by the warped, lysergic Shaft sample, Kim flexes her lyrical prowess and gives up the goods with slick cadence and tongue twists that pay homage to B.I.G and lingers long after the high wears off. — Tracy Kawalik

41. Junior M.A.F.I.A. – “Player’s Anthem”

Biggie’s gift was that he was equally gifted at rapping at stealing your girl as he was spitting about robbing dudes in Clinton Hill. On ‘’Player’s Anthem’’, he says ‘’rub your tities if you love hip-hop’’ but true to form, he is also boasting about how he’s been robbing dudes since he was Run DMC. Like ‘’Juicy’’, ‘’Player’s Anthem’’ is also a celebration of making it from selling crack in the hood to having caviar for breakfast and champagne bubble baths at night.

Lil’ Kim is in rare form here; the best part about BIG and Kim’s music together is you can feel the attraction that they had for one another in real life. BIG says that if robbery was a class, he’d pass it. Kim reminisces about being Keisha in New Jack City, packing MAC’s in her cadillac before Pun. At the same time, Kim never fails to remind us that she is the boss. She is teaching the game to all the D-Boys that think they have it.

To see BIG and Kim is to see two forces coming together with their own unique sexual energy. BIG, a heavy Dolomite meeting Richard Pryor; Kim, a “running the block with her man” version of Pam Grier. As a dark skinned Black woman, Kim was given a raw deal by society that has racist and sexist beauty standards. In a world that values lighter women, she was made fun of until her skin became light like those women she was pinned against. She wasn’t allowed to embrace herself like BIG was (Some of that is because of BIG himself; he wasn’t perfect). That’s unfortunate, because they were perfect together; there wasn’t a male and female rap duo that was better. — Jayson Buford

40. “One More Chance (Stay With Me) (Remix)”

The feel good music video for 1995’s “One More Chance” remix shows Biggie chillin’ on the stairs at a dimly-lit house party, which is tellingly chaired by rap’s original 320 lb. sex symbol, Heavy D. He’s talking his shit while receiving kisses on the cheek from a whole host of female admirers; it remains a beautiful time capsule.

It captures 1990s rap culture just before all the crippling paranoia set in (something Big arguably got lost in himself with Life After Death), with an infinitely cool Biggie rocking his navy blue Kangol like it’s a crown. But aside from capturing Biggie at his most carefree, the “One More Chance (Remix)” remains important to the late rap legend’s legacy because of the way it cemented his unlikely sex appeal, something that often gets downplayed when we talk about what made Brooklyn’s finest emcee so unique.

The original “One More Chance” was basically a horny horrorcore track, with brutal lyrics about shattering bladders and shifting kidneys not exactly ageing well. However, the remix traded those filthy bars for butter smooth boasts from Biggie about his “immaculate” bedroom skills. He wisely replaces the “I got that good dick” taunt for “I got that good love” on a soothing hook, which also contains seductive coos from Bad Boy’s own Charlie’s Angels, Faith Evans and Mary J. Blige.

This remix, which peaked at no. 2 on the Billboard 100, proved the Frank White and Big Poppa personas were two sides of the same coin, with Biggie effortlessly able to shift gears and make music that all sexes could dance along to (just like Tupac claimed he had advised Biggie to do). I don’t want to give the impression Biggie was the father of the body positivity movement, but he definitely wrote a blueprint for artists like Big Pun, Rick Ross and Fat Joe to follow, effectively creating a lane for overweight male rappers to convincingly channel their larger-than-life confidence into becoming improbable Lothario’s.

On this dance floor-filler, Biggie has a woman on each arm and a blunt in each hand, reigniting the magnetic lure of Barry White in his Can’t Get Enough heyday. Rapping against a laid back flip of DeBarge’s soppy-eyed “Stay With Me”, Big’s velvety flow is an ode to the art of fornication. He makes it clear that his size and appearance (“Heart throb never, Black and ugly as ever”) won’t get in the way of slick-talking your girlfriend into bed, and I can’t picture a day where this unshakeable self-assurance won’t feel contagious. — Thomas Hobbs

39. Mary J. Blige – “Real Love (Remix)”

Biggie’s appearance on Mary J. Blige’s “Real Love (Remix)” is another example of doing the most with less. It’s an efficiency masterclass. He spends just 20 seconds and under 12 bars on the remix to Blige’s first top-ten Billboard hit, coming in at the 2:20 mark and announcing, “What up? My time is up…” at 2:40. While the intro caught most of the attention with its sample of Betty Wright’s “Clean Up Woman”, Biggie spent the entirety of his verse over the drums of EPMD’s “So Whatcha Sayin’” courtesy of producer, fellow Brooklynite and childhood friend Daddy-O. “Look up in the sky, it’s a bird, it’s a plane/ Nope it’s Mary Jane, ain’t a damn thing changed,” is a picture perfect opening bar. This verse, like so many of Biggie’s features, leaves you wanting more. — Patrick Johnson

38. “My Downfall”

In 1997, rap kayfabe was at an all-time high. The intersection shooting where Biggie Smalls’ life was ended by shots fired into a Suburban door was the downturn of rappers keeping it “real” at all costs. Most of the time nowadays, we’re privy to rappers playing characters, rappers not really doing the things they say they do. After the murder of Tupac Shakur just six months prior, the likelihood of Big’s life reaching a violent, tragic end was somewhere south of the neighborhood of farfetched. I’ve read the word “prescient” a lot when reading about the violent paranoia of the final three songs on Life After Death. But it wasn’t exactly like Biggie predicting his own violent death was a miracle leap of psychic intuition.

In the final trilogy of songs on Life After Death, particularly “My Downfall,” Big shows his gifts of his imagination by melding the dark clouds of real life with lavish fantasy and deepening the Legend of Biggie Smalls as the most impressive folklore in this genre called rap. Only Biggie has such depth of range to conjure the image of his own funeral, brag about his forays into amateur porn, and add the origin of his lazy eye to his carefully and fastidiously crafted self-mythology. Only Biggie has the sense of humor to mistake heavy breathing on the other end of a threatening phone call for his wife.