Chris Mitchell stands and eats with the wedding photographers.

A quarter century ago last month, I left the crib and popped a dubbed copy of Hell On Earth by Mobb Deep into my Walkman, pressed play and headed to school. My friends and I would always claim spots on the 220 bus’ top deck, and today, the air was dense with adolescent bravado. Going to school in another borough always felt like I was leaving one world and entering another, but this time, as I sat on one of London’s world-famous red double-deckers driving over the Mitre Bridge listening to the new Mobb Deep album, I found myself teleporting to the concrete lava of New York.

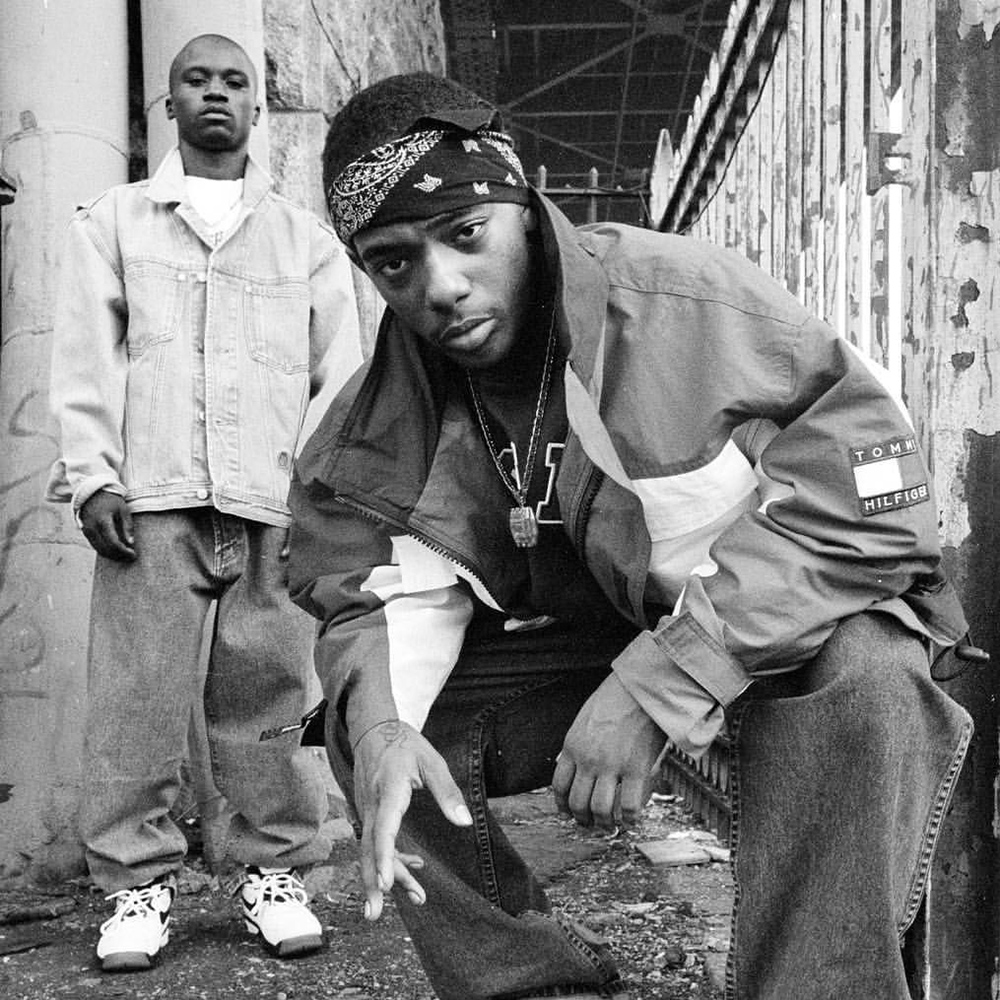

Hell On Earth by Mobb Deep was released on Tuesday November 19th 1996 on Loud/RCA, right at the tail end of rap’s second golden era. Just three years earlier, a fresh-faced Havoc and Prodigy had dropped their debut, Juvenile Hell, on 4th and Broadway. The album didn’t sell, and they ended up losing their deal, but all they needed was a second chance. By 94’, Mobb Deep inked a new contract with Steve Rifkind’s Loud Records and their sophomore album, The Infamous, received glowing feedback from the streets and critics upon release in the spring of ’95. Its balance of knucklehead nihilism and world-weary wisdom that defied its creators’ teenage years was both enthralling and terrifying. Mobb Deep encapsulated the subtextual menace prevalent in the mid-90s New York ecosystem. The perfect quiet storm of the right label, right sound and right time – along with their creative resilience – set in motion momentum which continued into Hell On Earth.

The album was recorded and released when shots were being fired, both on wax and in real life. The unfortunate demise of Tupac Shakur two months before Hell On Earth’s release was a sobering reminder that celebrity was inadequate protection against a violent death. Early in 1996, Tupac released “Hit’ Em Up,” a Death Row Records funded attack on East Coast emcees, including Mobb Deep. Depending on who you ask, Pac was pissed off at Mobb Deep after they declared “thug life, we’re still living it” on “Survival Of The Fittest” from The Infamous, given Shakur’s stomach famously sported the words “thug life” in bold letters. Others would also cite Mobb Deep showing solidarity with Capone-N-Noreaga on “L.A., L.A.” and clapping back at Snoop Dogg and Tha Dogg Pound for putting their boots to the Big Apple’s buildings in the “New York, New York” video.

Whatever his reasons, the Mobb air out their grievances on the album’s second track, “Drop A Gem On ‘Em.” Without mentioning Tupac by name, the pair goes in over a sample of The Whispers’ “Can’t Help But Love You” and create one of the most scathing war dubs known to man, woman, and child. With extreme callousness, Havoc highlights the longstanding rumor of Shakur being the victim of sexual assault during his time on Riker’s Island. Prodigy references the 1994 shooting at Quad Studios where Pac survived multiple shots to the body. Slicing through any restraint, Prodigy reveals that Shakur was forcefully relieved of his jewellery and tags a monetary value of “sixty g’s worth of gun clappin” as the cost of the chaos. Mobb Deep planned a video for “Drop A Gem On ‘Em,” but in light of Tupac’s death and respect for his family and friends, they ceased all promotional efforts with the single release. The song still made it onto Hell On Earth.

The album’s second single and title track meanwhile, is like the slow roll of a freshly minted hearse approaching one’s final resting place. The mournful inflections of Havoc’s production are like a portal to the sinister side of eternity. Assuming the role of the Phantom of Crime Rap, Prodigy further cements his status as the master of the first bar with: “the saga begins, begin war / I draw first blood, be the first to set it off”. Havoc closes his single verse on the song with “Scarface, rest in peace!”

This posthumous shout out is for Twin Scarface, the brother of IM3’s Twin Gambino.

Scarface died during the recording of the LP, and Schott “Free” Jacobs shared the tragic circumstances of his passing via email.

“We were recording, the crew ran out of smoke and made a weed run to Harlem. Godfather III was driving. Somehow, he lost control of the vehicle; it hit a divider, and it flipped over. Twin Scarface broke his neck” – Schott “Free” Jacobs

This specter of death is a constant thread in Mobb Deep’s music. The swift and cruel loss of life finds its juxtaposition among the extinction of innocence, opportunities and freedom – all of which are, sadly, expected outcomes of the trife life. In a 2011 interview with Complex, Prodigy spoke with Insanul Ahmed, reflecting on how death was always around the corner for him and his crew:

“We had a lot of people who died during the making of that album; we had at least five of our friends and family members die. It took us two years to make that album because of all the death that was happening around us. That’s what Hell On Earth was about; we felt that we were living in hell.”

Within a few short years, Mobb Deep was mourning the loss of Havoc’s brother, Killa Black, their close homie Yammy, and Prodigy’s father.

When the crew wasn’t facing death, they were dishing it out on record. From the jump, all hell breaks loose on the first track, “Animal Instinct.” Havoc’s unmistakable baritone booms through the speaker as the crew doubles down on the darkness of their newly refined formula. On the one hand, Hell On Earth meticulously and fearlessly breaks down themes synonymous with the street experience like crime, drugs and violence. On the other, like much of Mobb Deep’s output, the album is a front line report from those who lived it, detailing generational trauma, socio-political inequalities, and the state-sanctioned poverty experienced by Black youth. Throughout Hell On Earth, Mobb Deep escorts the audience through an infernal climate where the battle is all against all, and the law of the land is brutal and solitary. The feeling is chillingly vivid and immersive, straight from the source. Tracks like “Bloodsport,” “Can’t Get Enough Of It” and “Man Down” amplify these sensibilities with deafening realness. On the latter, Prodigy’s longstanding lust for blood is apparent when he proclaims, “we face splashing, dope fake’s ice-pick stabbing / He slow leakin’, eternally bleedin’ for speakin”.

The peril persists on “Nighttime Vultures.” Here, Raekwon is credited as Lex Diamonds, a nod to his Cuban Linx project, recorded alongside The Infamous and released three months later. Prodigy opens up the song covered in claret and has flashbacks of a shootout the day before, using cleverly coded semantics to go into depth about narrowly escaping a robbery attempt.

Finally, “On G.O.D. Pt. III,” the album’s thematic climax, Havoc samples Giorgio Moroder’s Tony’s Theme from the Scarface soundtrack. The song opens up with a skit of Mobb Deep and their posse showering a ubiquitous rival with a flurry of gunfire from a window. Seconds later, Havoc and Prodigy further innovate in the art of violence, advising to “never second-guess a cat who hold gats concealed”.

Throughout Hell On Earth, Havoc skillfully stitches together a patchwork of bleak and brooding textures, producing the entire project, the only one he’d score without outside assistance. That goes a long way towards making it feel like a psychological thriller. Havoc took notes from A Tribe Called Quest’s Q-Tip, a mentor figure who assisted on The Infamous, an experience that gave Havoc the confidence to step behind the boards for an entire project. In the years following Hell On Earth, Havoc established himself as a top-tier producer with a style that was akin to walking down a dimly lit alley with shadowy figures constantly dashing past your line of vision.

Meanwhile, Prodigy’s stanzas on Hell On Earth are some of the most meaningful verses committed to paper. The visceral penmanship he displayed on this album helped propel him into the space reserved only for the rhyme writing elite. His turns of phrase are simultaneously spiritual, scientific, abstract and direct. Listening to the album’s final song, “Apostle’s Warning,” Prodigy’s leaves a venom laced impression by creating “a rhyme labyrinth like poisonous cannabis”.

In the twenty-five years since its drop date, Hell On Earth‘s classic rank has been etched in hip-hop culture with fire and brimstone. Havoc and Prodigy found themselves buried among burning barrels with their nostrils twitching from the stench of charred dreams, engaging in a stare down with their own mortality. The constant jostling between living and dying positions despair and death as not only inevitable but in a true morbid fashion – a form of escape. On June 20th 2017, Prodigy passed away after suffering a significant medical episode resulting from his life-long struggle with sickle-cell anemia. Hell On Earth is a crucial part of his legacy, and while he may not be here in the flesh, his spirit remains and his literature stands colossal. Havoc also keeps his partner front of mind for a new generation of dunn language enthusiasts through a constant stream of pictures and videos on his social feeds, all while producing for various acts, including Conway The Machine, Method Man, Flee Lord and Cormega. With Hell On Earth, Mobb Deep created arguably their best album and the second sure shot in a hat-trick of bonafide classics, which zealous new heads and seasoned soldiers alike still celebrate today.