We spoke with Wiki about his hometown New York City and the concepts around his Navy Blue-produced album Half God.

It’s no secret Patrick Morales, better known as Wiki, loves New York City. Wiki grew up in the Upper West Side of Manhattan, just a few stops on the 1 train from Time Square. Like most locals, Wiki understands there’s nothing like home. And one of the most painful things a person can witness is losing their home or watching it change until home becomes unrecognizable. On Wiki’s new album, Half God, which is entirely produced by Sage Elsesser, AKA Navy Blue, Wiki condemns the damaging effects of gentrification in his city. Half God is a representation of his love for NYC, and a celebration of hip-hop and its culture.

Wiki met Navy Blue one fateful night in the city through mutual friends who were skaters. On a tour with Earl Sweatshirt, Sage and Wiki would got to know each other better. A feature with ANKHLEJOHN became the reason Wiki and Sage hit the studio together. “ANKHLEJOHN was like, ‘Do you want you to join Sage?” He said you should get on his ass. So once that happened, that shit was fire,” Wiki said over a phone call last month. “So then it was kind of like, yo, let’s keep working,”

Released in September, Half God is contemporary NYC rap at its finest, with soulful chops and looped instruments that are, by design, meant to compliment the vocalist and don’t overpower. Sage’s production provides a spotlight to Wiki’s lyrics and rhyming prowess. Like on “Roof,” where he contemplates between leaving and seeing something new, or staying home in the city where everything’s changing:

“Do I wanna travel or remain with the same view from this roof that stays the same but always changes?”

We had a long conversation with Wiki about the state of New York City and the concepts around his new album Half God.

What initially drew you to Sage’s production?

Wiki: For me it’s what it got out of me. I like to rap on all types of shit. Just hearing something I like and the beat and then I’ll just go for it. But with his production it’s like what I felt like I always wanted to make. You know what I mean? There was this certain classic element to it without it being like some throwback shit. There’s a timelessness to it too. I was like, “damn, this is what I always wanted to do.” It was like most shit I ever wanted to listen back to.

I feel like his production puts more emphasis on your lyrics. Was there any intention on doing that?

I think Sage knew that his production could get that out of me and that’s why he really wanted to work with me and I wanted to work with him. We started working… but then after the first three joints we made, we both knew we needed to make a project. It just started getting better and better. But not only better and better — more realized. It wasn’t just three random joints. It was like, “this is developing into something more.” So I think he was definitely really aware of that. And in terms of the stuff he was sending, I think there’s a certain simplicity to a lot of it really.

That’s also what makes the record so good because it wasn’t overthought. It wasn’t trying to be too much of what it didn’t need to be. I was saying to Sage, “Bro, look how well the record’s doing… we did this shit with raps and beats.”

It doesn’t need to be overthought or overproduced. Which in the past I think that’s something I always just tried too hard to do. I was like, “yo, I got to make this crazy.” And the ironic part is that once you start doing that too much, it’s actually not as pure. For this record, it would have been weird if we started getting all the instruments on there and overdoing it. It wouldn’t have been the same thing.

“Not Today” has some of the most potent rapping on the album and it’s the first track. There’s a lot of negative feelings towards the state of New York City. Can you elaborate more on that?

I like “Not Today” because I wrote it as I knew it was going to be the intro. Sage was like, “Yo, this should be an intro.” And then I wrote it as an intro and you see it goes from “Not Today” right into “Roof.” And it’s that place I was at right before when I got into my bag. I’m going through it and shit but that was where I was at. You know that feeling when it’s like everything’s fucked up? You’re feeling negative. You’re at the end of the road. You’re feeling like you’re going to give up, but then it’s like, “no, no, no, no, no. I got to make it through to the other side.”

It’s still in that dark, there’s just sirens going on in the back. To me it goes into “Roof” and then it’s that release. And then “Roof” is getting all the shit off my chest in a positive way on my roof and then it gets into the record. Because we were like, “Should ‘Roof’ be the intro?” But then, to me, “Not Today” is that first little perspective of where I was at before the record. And it’s like I was barring up on it because I was like, “Yo, I need to let them know what this record is supposed to be like.” That’s the highlight of the record. Even though the songs are written and there’s stories going on, it’s bars. And that’s what I like about it. It’s something someone said to me once, recently. They were like, “Yo, you’ve already proved yourself as a rapper. You should do the whole next thing.” And I’m like, “I like that and I want to do all types of shit but no, you don’t understand. Rap is an art to prove. I’m going to make the best art all while proving myself as a rapper.”

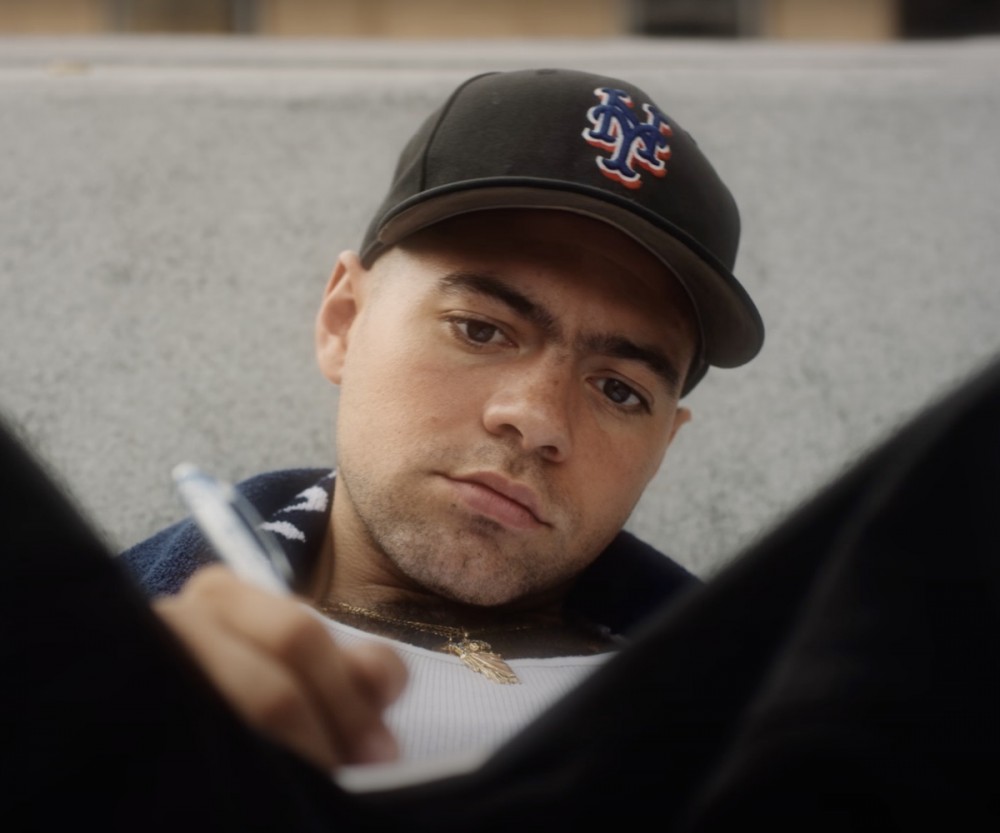

On Wiki’s new album, Half God, which is entirely produced by Sage Elsesser, AKA Navy Blue, Wiki condemns the damaging effects of gentrification in his city. Photo Credit: Jacob Consenstein

Gentrification is obviously the major theme of the album. How has it affected you in your neighborhood?

I mean, I’m from the Upper West Side. I’ve lived downtown. I’ve lived in Brooklyn. So you see different sides to it and shit. A lot of the homies I came up with were from Harlem, too, so then there’s that side. I have a lot of friends from downtown. So you see it from all these sides but the one common thread is just that idea of losing your home or identity… our shit’s constantly changing since we were growing up. I live in the LES now, and sometimes I’m like, “Well, this is some LA shit.” That certain type of LA where it’s like everyone’s just out getting quirky and they’re just in their little bubble. I’m like, “Bruh, this shit is wacked.” It’s weird but then also then there’s elements to that, too. The actual real shit is displacing people that are from these places. And the idea of living in New York is like a constant competition. Real estate has always been the real thing. You can never win. And I feel like I touch on that in “The Business.”

But at the same time understand all perspectives because — I even say it later in the album on “Grape Soda.” I’m talking about my homie Johnny, he was from out of town because he held it down harder. I have mad homies from out of town, and they become part of the city and they give back to the city, instead of starting this new thing and then being trapped in the bubble away from the city and away from the locals and shit like that. So there’s definitely a way. It’s not just cut and dry. It’s not black and white. But it’s definitely something that affects everyone in the city at the same time.

In quarantine, there’s that era when everyone left except the people from New York and the people that have been in New York for a minute that were settled. So then in that period it was ill. And then when it came back, there was all this, “Oh, New York’s back” and it was like, “Bruh, this shit is whacked.”

While recording this album did you ever think about where you grew up?

Yeah, I mean, it comes up on the album a bunch. I think maybe more the high school years, I would say. It’s hard to remember all that shit but you have those early memories. For me, it might be going over to Amsterdam and Columbus and playing basketball in the park over there. And then you start to see more of hip-hop. Because that’s where there’s more Puerto Rican and Dominicans over there. And you start to see those elements and early on see them live in front of you. I think that affected me OD too, because it’s like, you’re actually seeing it in person. I like to feel this shit organically because you could get a lot of that shit on the internet or whatever.

When I got into grime shit it’s because I was with Skepta. When I was on some footwork shit, it was because I was with DJ Earl and them in Chicago. The Internet’s dope because you could become an expert on all this shit. But I like to stray away from that a little bit and just try to let the shit come to me organically. So that’s what I like about the city, in general, because it’s growing up you’re out. No matter what internet or not you’re still out in the streets. You see it in the youth in New York still.

On the album you talk about being unsure if you even want live shows to return. What has the pandemic been like for you?

I love playing live. There’s nothing I love more. That’s the only time I feel real, the times when I’m rapping. It’s obvious, you do want it to come back but there’s that thought of, “damn, this is kind of nice. The world is taking a break.” And it’s like you don’t got to deal with all the stresses you always have to deal with and you don’t have to go on tour constantly. And it’s that idea of also being jaded and shit. After you play shows for so many years and it’s like you’re just doing it. It can become a little tiring. So it’s just reflecting. But I’ve gotten on the mic a couple times. I’m loose and now I’m hyped to play. I’m ready to go out. I want to play this album. I don’t want to wait forever so I’m trying to just get out and play shows.

“All I Need” features a verse from Earl Sweatshirt. How did that song come together?

That song was one of the first ones we did because I was out in LA. Sage and I pull up to Al’s studio and then we were just kicking it for a couple days. And Sage then just put on that beat one night after we had dinner and we came back. And me and Earl just both started writing immediately and then we both laid it and then after a while it was up in the air. It would’ve been on my joint or his record because I think, at one point, it was maybe going to be on his record. And I was hyped for that, but then I’m really happy it ended up on mine because I feel like it really fit in with everything and was one of those starting things that really lit a fire under my ass and was like, “all right. You got this.” It made me feel confident. It made me excited to keep making music and then it was this spark I needed too.

I think the fact that it got to live on the record was sick and it was dope to be able to have Earl on there, too, because it’s something I know that he really wanted for a minute. I’ve been wanting to work with Earl since we did [“AM // Radio”] a minute ago.

“Gas Face” is another one of my favorites on the album. You mention meeting Bun B. How did that go down?

I met Bun B when I was on tour with MIKE. We played in Houston and he pulled up. I guess he’s cool with MIKE and shit and then I got to meet him briefly. But he was a mad nice dude. Bro, it’s like that Kanye [West] line. Bun B’s mad nice, bro. And you know how people are like, “Oh, they’re really nice.” And they’ll be fake nice. He actually looks in your eyes. Gives you the time of day, for real. So now Bun B’s mad cool. And I’m pretty shy. I think I told him that. And then I also told him that used to be my shit in high school. Rob, my older homie, put me on him and I used to listen to all that shit.

That’s when he started discovering because I was always into that old shit when I was in high school. And then discovering shit from outside of New York that was old, you know what I mean? Classic shit from outside of New York. It was like a whole ‘nother world and it opened my head up OD because I was like, “Wait, this shit is sick.” And then, so I got to meet him and I also remember just asking him about “Purple Rain” with Beanie Sigel. He was like, “Oh, yeah, I feel like that was yesterday. That was a random one to bring up.” I was like, “I need to ask him about this joint because that joint’s hard.” That’s the highlight of that one, giving a lot of shout outs to the people that kept it real, kept it underground, and kept it hip-hop even in their own way, like Three 6 Mafia or UGK.

At the same time [with “Gas Face”] I’m talking about DOOM. I’m talking about pre-DOOM and dealing with the shit that made him go the path he did. But that it couldn’t have been better that way. It needed to happen that way. In “Gas Face” I’m talking about [A&R] Dante Ross. Because I had a meeting with Dante Ross hella early on and he was just on some funny shit. And I felt really bummed about that for hella long. And then once I started to see, I was like, “oh, damn, people have been hating on Dante Ross forever.” I was like, “Oh, all right cool.” And then that’s like what I’m talking about referenced Dante Ross in “Gas Face.” I just was trying to show it’s even in that it’s giving a little glimpse into the history lesson in hip hop but it’s also talking about my own experience too at the same time.

There’s so much love resonating from all the tracks. You love the city and that’s the music.

I feel the same way. You feel it in that way. You hear it. It’s not even in that way. I feel like maybe you get more confidence recording over the years too. And I feel like I felt confident in my voice on this outlet. You know what I mean? This is just me, boom. And confidence as a rapper in hip-hop, in my place. So it’s like having that perspective I think is dope. And I think that is what made it dope. And I think also getting a joint with Earl and getting in and out of the studio and doing it and being around people that were my peers. [Those I respect] also respected me and gave me that confidence I needed.

__

Anthony Malone, is a music journalist based in Brooklyn, NY with a love and passion for everything hip-hop, especially from NY. Rap music is his life and he couldn’t want it any other way.