Screenshot via Pranav Trewn

Pranav Trewn finds peace in his vinyl record collection.

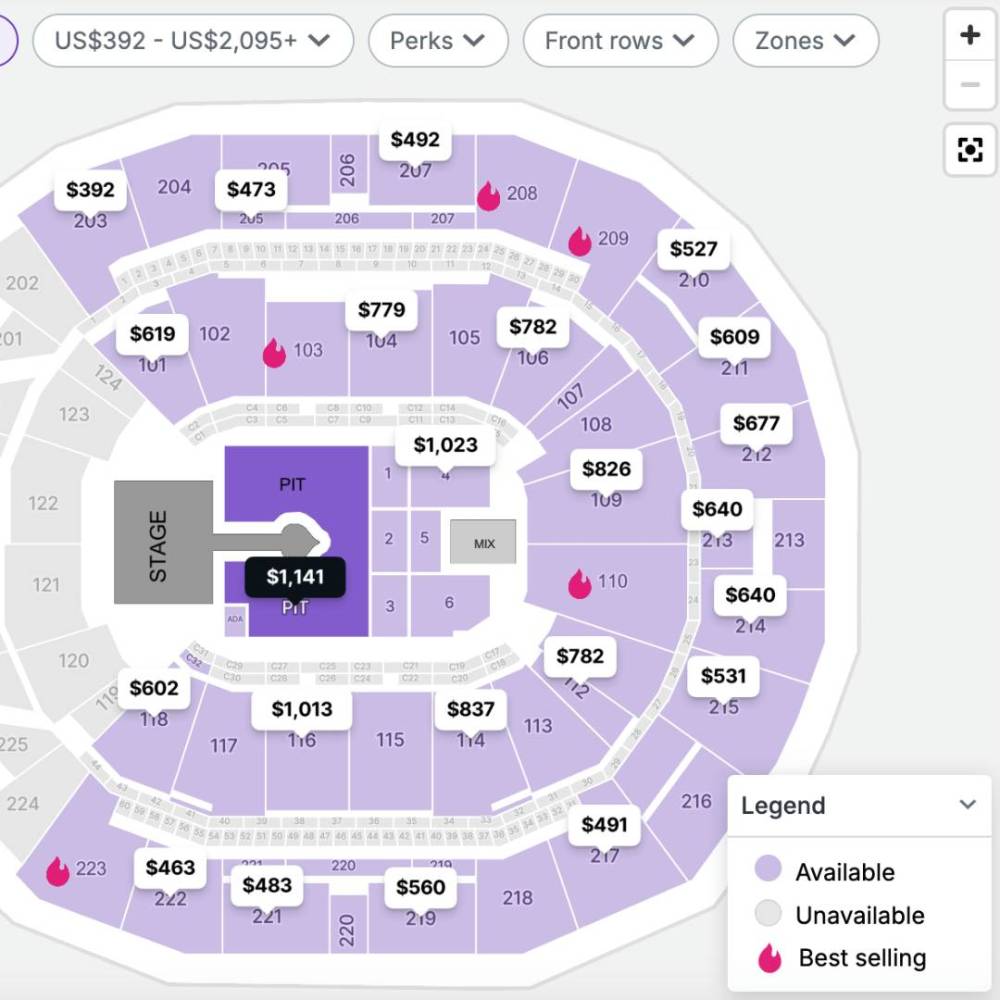

Buying concert tickets can often feel like managing a stock portfolio. I put money down today for shows months from now, and watch in the interim as the value of those tickets oscillates on the secondary market. For Charli XCX and Troye Sivan’s “SWEAT” tour, I bought low (i.e. pre-Brat) and stood to sell high if I wanted to. With the National and War on Drugs tickets I had for October, a last second commitment left me scrambling to find a buyer and ultimately eating the sunk costs.

Arbitrage opportunists have turned this volatility into a dishonorable business, making our current resale infrastructure effectively predatory by crowding out fair-minded peer-to-peer transactions. These days, buyers without a presale code and a favorable draw in the Ticketmaster queue must face the price-gouging of professionals hoarding the supply on third-party marketplaces well before the general sale. As a seller, these platforms like StubHub and SeatGeek force you to inflate your list price if you want to break even by taking a substantial cut of each sale through exorbitant fees. Everyone is worse off in these atomized digital auction houses we are forced to use.

Traditional economists would argue that this shitty equilibrium of artificially-induced scarcity and middlemen interference is the result of a market failure: artists are charging too little at face value (and they wonder why they don’t get invited to parties). That conclusion is logical – if there isn’t a margin to be made, resellers wouldn’t be swarming the market – but it’s not reasonable. For one, no artist outside the K-pop machine wants a reputation for actively exploiting their audience’s demand, nor would most want to perform solely to the richest of fans and their spoiled kids. There are many factors that go into “pricing” a performer, but overcharging can work to erode their long-term value.

Better to leave the reputational damage to the scalpers, a largely anonymous mass ready and willing to take the brunt of the “bad guy” label. This has long been an issue; even as early as the 1800s it was common to see “sidewalk men” hawking at the door marked up tickets they had previously bought in bulk from box offices. Promoters were once on the same side as fans in their distaste for this practice, bemoaning third parties squeezing an independent profit on their inventory. But at least the scalpers of yesteryear didn’t have bots to automate and limitlessly scale the physical labor required of their trade. That’s why the ticketing “innovation” of the last few decades has mostly involved efforts to make reselling more difficult, such as by filtering out non-human buyers, identity matching attendees to the original ticket holder, and even threats to cancel tickets listed on secondary sites. But as the old adage goes, if you can’t beat your enemy, join them.

It’s an open secret that fans don’t even stand a fair chance during on-sales because a portion of the available inventory gets sent directly to resellers. Live Nation has come under fire for this practice of moving artists’ tickets straight to resale, but smaller companies are in on the game as well. Take a look at Lyte, which over the years morphed from a peer-to-peer ticket exchange into a place for promoters to scalp their own events, with the upside of those significantly spiked sales to be split between the parties. Lyte recently played this business model with two independent festivals, Chicago’s North Coast and Ohio’s Lost Lands, before suddenly collapsing in September and forcing them to litigate to reclaim their shady revenue.

Personally, I’ve drawn for myself a soft line in the sand around scalping, largely trying to sell surplus tickets I hold first at face value to friends and family, then if needed on resale sites at a break even price once the platform takes their cut. This is, I’ve come to realize, a minority approach. Online sales are sufficiently depersonalized that few feel the ickiness of charging a fellow fan locked out of an event twice what you paid to make a quick buck. If you do have qualms, you can still rationalize your behavior through reasoning that if you underprice your ticket, another scalper will just flip it again and take the money that’s on the table. Better that profit goes to you than the actual scum right? It’s a slippery slope, such that even when Ticketmaster attempts to limit access to professional ticket brokers – through their Verified Fan program and behind-the-scenes algorithms that try to suss out dedicated resellers – fans facing financial temptation come to take on the role for themselves.

So this isn’t simply a problem of bad actors that need to be weeded out. What then as a society can we do? Some artists have stepped up their advocacy on behalf of their fans, most prominently Robert Smith of the Cure. Beyond simply accusing the industry of unfettered greed, he has made the appeal that what’s better for fans here will ultimately serve to benefit everyone: “If people save on the tickets, they buy beer or merch. There is goodwill, they will come back next time. It is a self-fulfilling good vibe and I don’t understand why more people don’t do it.”

I appreciate his efforts, but he alone won’t move the needle, nor could any substantial block of like-minded artists unless they find a way to break the Ticketmaster/Live Nation monopoly. They will hopefully be assisted by the Justice Department’s antitrust lawsuit, but any verdict is likely a long way off. And even if the government is successful, there is no guarantee new entrants would make this industry substantially more consumer-friendly, rather than replicate the same broken business models. Like mutating viruses developing resistance to current vaccines, there are always new innovations in fuckery companies learn over time to dodge regulation.

Perhaps what we need then is for consumer-friendly innovation to evolve faster. Among the most sensible I’ve seen has come from a band I had never previously heard of, Stick Figure (a nice side effect for artists doing their part is the positive publicity). For their 2024 tour, the roots-reggae outfit offered refunds for buyers up to 10 days before a show. The band had to cover the costs of the refunds themselves, since of course promoters did not want to give an option for fans to simply get their money back. By doing so, Stick Figure was taking on the risk promoters typically cite as to why a common sense refund policy can’t be implemented, that indiscriminate refunds would lead to heavy losses at the last second.

The result of their experiment refutes that claim. Of the 135,446 tickets the band sold over 16 dates, they only had to process 750 refunds. That’s about half a percent of revenue. The band’s manager Thomas Cussins called this an unqualified success: “As this tour was largely sold out, nearly all refunded tickets were resold. Even in the case of a less well-attended tour…There is a strong case to be made that losing less than 1% of tickets later is still worth the overall boost in consumer confidence.” His take is that the security of having a refund option will drive sales from otherwise risk-averse buyers. Anecdotally, I am sure everyone can think of shows they would have attended had they not needed to worry about potentially dealing with the headaches of the current resale process.

Slightly less risky for artists and promoters is to implement a refund policy through their existing waitlists, which put buyers for sold out events in a queue to purchase spots when inventory becomes available. Right now, these waitlists are mostly supplied by the rare default from a payment plan purchase and promoters letting go of a small handful of previously withheld stock. But if the person on top the waitlist is ready to buy and someone with a ticket is ready to sell, why make these folks go to a third party when they could be facilitated directly by the ticketing service? This would keep resale transactions more secure from scams since the ticket is being transferred on the platform directly at the time of sale, and prevent any losses to the promoter because the refund is only issued when there is a buyer taking the original purchaser’s place.

So why doesn’t Ticketmaster do this? In part because they want everyone to list resales on their own site, letting them tack on a second round of fees to those who already paid them for the original ticket. Ultimately, it all goes back to the original sin of the industry, in which the biggest promoter is also the biggest ticket vendor and is also now among the largest resellers. It’s simultaneously vertical and horizontal integration – a metastatic mass bleeding dry everything organic in the business. As with cancer, most of our existing treatments are limited in their effectiveness, and often come with painful side effects. And everyone in this business has little incentive to find a cure since the collateral damage on their customers is just too profitable. It’s a boom time for live music, unless you’re actually trying to go to the show.