A look at how the video for “Untitled (How Does It Feel)” made — then almost broke — D’Angelo.

In the five years between his debut album, Brown Sugar, and Voodoo, D’Angelo’s personal and musical career had changed. The artist suffered from writer’s block after spending two years touring for Brown Sugar; only after his son Michael was born (with then-girlfriend Angie Stone) in 1998 did he feel inspired to write music again. During this time, he had also been inducted into the Soulquarians, an Avengers-like superteam of rap and soul luminaries whose members — Bilal, Common, Erykah Badu, J Dilla, Q-Tip, Questlove, and others — favored unconventionality and artistic integrity. That the singer found a kindred spirit in The Roots’ Questlove — who was integral to the recording process of Voodoo — isn’t surprising. They shared a desire to celebrate and study the greats — Jimi Hendrix, James Brown, George Clinton, Marvin Gaye, Sly and the Family Stone, Stevie Wonder and, of course, Prince. These artists served as the foundation for Voodoo.

“…the biggest influence on the record was someone who never came to the studio: Prince,” Questlove said in a 2000 Rolling Stone interview. “Way after Voodoo was finished, D and I sat down and listened to it, and we both admitted that this was our audition tape for Prince.”

If there’s any song indicative of the late Purple One’s influence on Voodoo, it’s “Untitled (How Does It Feel).” Reminiscent of the ballads the Minneapolis musician made during the ’80s and early ’90s — particularly “Do Me, Baby,” “Scandalous,” and “Insatiable” — there have been countless forums made debating if “Untitled” is plagiarism or an homage to Prince. (The latter is more apt, with Questlove even declaring the track “our homage to the Controversy-era Prince” in a Voodoo album review.) The most notable nod to Prince in “Untitled” is D’Angelo’s falsetto: an androgynous croon that shifts in multiple tones throughout the song’s seven minutes. At times, it’s mumbled and quiet, his pleas practically indecipherable. Others, it’s confident and triumphant, the lightness of his voice propelled by cathartic screams meant to make you feel the satisfaction his lover gives him.

Anchoring D’Angelo’s vocals is the instrumentation: Raphael Saadiq on bass and guitar; the late Chalmers Edward “Spanky” Alford on guitar; and D’Angelo on additional instruments. It’s improvisational yet structured, loose yet precise — a sensual and erotic ballad swung hard by a cool backbeat, rimshots echoing into a void of blues, funk, and soul driven by soft guitar strums and bouncy bass. There’s a vintage grit to it too courtesy of audio engineer Russell Elevado, whose use of vintage analog equipment and mixing gear made “Untitled” (and the rest of Voodoo) feel and sound just like the classics D’Angelo sought to emulate.

“Untitled” was the third of five singles released for Voodoo, succeeding more hip-hop-oriented songs “Devil’s Pie,” produced by DJ Premier, and “Left & Right,” featuring Method Man and Redman. Of the two, only “Left & Right” received a music video, which offered a glimpse at what was to come with the music video for “Untitled.” “Left & Right” followed a conventional ’90s-era video treatment. The club is the setting, with a flurry of hazy scenes showing people dancing before Redman offers his guest verse. D’Angelo doesn’t even appear until 30 seconds into the video — the scene briefly showing the singer shirtless with a chiseled and muscular build that’s partially covered by a low-slung guitar. It’s these scenes that separated “Left & Right” from music videos from Brown Sugar. Whether the title track or “Lady,” D’Angelo was always fully clothed, his voice the representation of his sex appeal. “Left & Right” offered a subtle change to form, both D’Angelo’s body and voice now representing that.

Then, came the music video for “Untitled.”

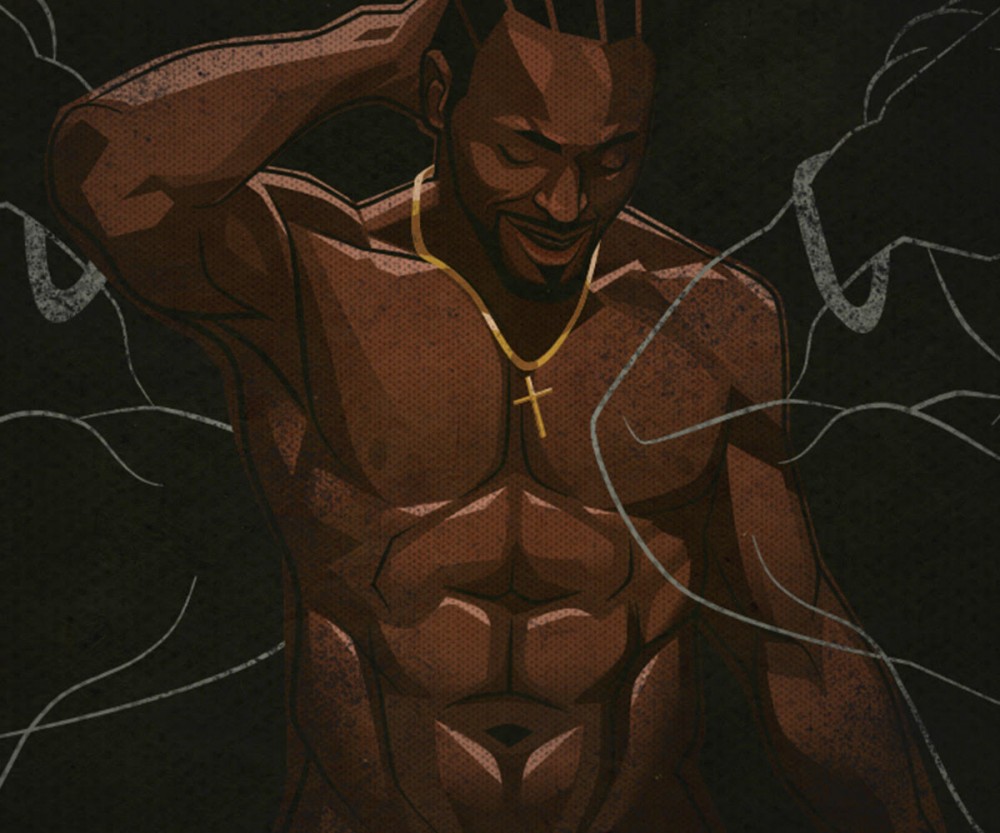

For most of the four-and-a-half minute-long video — which was directed by Paul Hunter and Dominique Trenier — D’Angelo’s upper body is the focus. The camera expands from his black braids, brown eyes, and his plump, licked lips, to show a glistening and chiseled chest and V-cut abs, the screen cut off right at the point of his waist to where a viewer can’t help but wonder if he’s nude or not. There’s nowhere to avert your eyes as the one-shot video offers a voyeuristic exploration of D’Angelo’s body. It’s intimate, provocative, sensual, vulnerable — a hypnotizing performance that offers no relief until its over, beautifully capturing the pleasures of sex without being explicitly overt. The video is subversive, a display of black masculinity that’s affectionate but confident, and delicate but strong. A middle ground between Tupac’s infamous bathtub photos and the first 30 seconds of Prince’s “When Doves Cry” music video.

“Untitled” was distinct from other hip-hop, R&B, and pop videos because of this. Unlike the hedonism and hypermasculinity found in hip-hop and R&B videos or the teenage-like fantasies found in pop videos, “Untitled” felt real and offered a display of blackness uncommon in music videos at the time. Even watching it now, it’s incredible to think such a video appeared alongside Christina Aguilera’s “What A Girl Wants,” Britney Spears’ “From the Bottom of My Broken Heart,” and the Backstreet Boys’ “Show Me the Meaning of Being Lonely.”

The music video for “Untitled” also greatly impacted the commercial success of Voodoo.

“Probably one of the most controversial new videos in rotation, it has given his project the burst of energy it so desperately needed,” Datu Faison wrote about the video in an issue of Billboard.

The track peaked at number 25 and number two on Billboard‘s Hot 100 and Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Singles & Tracks charts, respectively. And Voodoo debuted at number one on the U.S. Billboard 200 chart, selling 320,000 copies in its first week. Through the “Untitled” music video, D’Angelo gained mainstream attention that he didn’t have previously. But he also became a sex symbol in the process which, although initially harmless, grew to become a problem when he embarked on a tour in support of Voodoo in March 2000.

Prior to that tour, a New York Times piece was published that highlighted how divisive the “Untitled” video was, with Douglas Century writing: “Most women watch and swoon; many men turn away and scowl.”

“It’s about time that girls had something luscious to look at while they’re listening to a song,” Danyel Smith, the former editor in chief of Vibe, said in the same article. “For years, men have been treated to breasts and butts along with their favorite songs, and women have had to just sit there and endure.”

Source: Artist

By the time D’Angelo started the Voodoo tour, the idea of him as a sex symbol had eclipsed him as an artist. Journalists who attended the musician’s tour-opening Los Angeles shows at the House of Blues offered firsthand accounts of seeing women “grab his legs, his stomach, his crotch,” and screaming at him to take off a tight black tank top he wore during the concerts.

“It feels good, actually, when I do it,” D’Angelo said at the time to Rolling Stone. ‘But I don’t want it to turn into a thing where that’s what it’s all about. I don’t want it to turn things away from the music and what we doin’ up there.”

‘Sometimes, you know, I feel uncomfortable,” he added. “To be onstage and tryin’ to do your music and people goin’, ‘Take it off! Take it off! ‘Cause I’m not no stripper. I’m up there doin’ somethin’ I strongly believe in.”

But the music became secondary to womens’ “Untitled” fantasy. The concert served as a continuation to the video, and it ultimately took its toll on D’Angelo as he simultaneously tried to be — and fight against — a projection of himself he couldn’t control.

“We couldn’t get through one song before women would start to scream for him to take something off,” the late Roy Hargrove said in an interview with Spin in 2008. “It wasn’t about the music. All they wanted him to do was take off his clothes.”

About three weeks’ worth of shows were canceled toward the tour’s end in late 2000. Upon returning home, there were plans to release a live album and a new D’Angelo album, projects that could’ve led to him becoming a superstar. But it never happened. Instead, D’Angelo destroyed the image of himself that contributed significantly to his fame to the point of being unrecognizable, and wouldn’t make his return to music until 2014 — fourteen years after Voodoo — with Black Messiah.

In Devil’s Pie, the 2019 documentary that details his disappearance from the public eye following the Voodoo tour, it’s evident how the video’s impact still lingers with him. How, despite making a critically-acclaimed comeback and resuming performances throughout the world, there’s still the anxiety and insecurity of wondering if D’Angelo the artist will ever truly eclipse D’Angelo the sex icon.

The “Untitled” music video marked a tragic end and a new, tumultuous beginning for D’Angelo. It became the mission statement for an artist perceived to be the next great coming in R&B, only to incite the lowest point of his artistic career and personal life. It’s a moment that’s now a little more bittersweet to enjoy: an undeniable classic that conveyed so much with so little, and became one of the greatest music videos of all time. But at the expense of an artist who almost didn’t recover from it.

purchase D’Angelo’s Black Messiah here.

__

This story was originally published in 2020

Banner Graphic: @popephoenix for Okayplayer