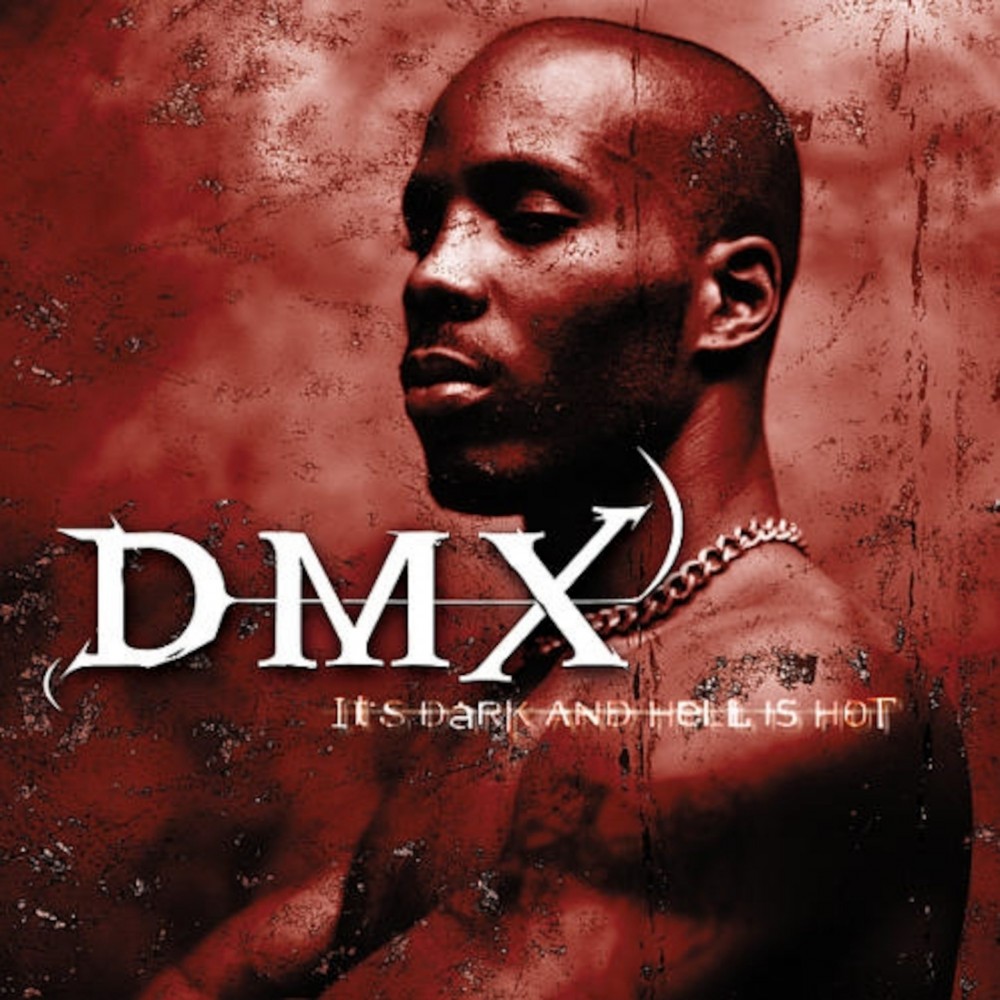

The Secret History Of DMX’s ‘It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot’

We spoke with Ruff Ryders founder Joaquin “Waah” Dean and producer Dame Grease about It’s Dark and Hell is Hot, DMX’s classic debut.

Having spent most of his childhood in and out of children’s homes, a teenage DMX would wander the streets of Baltimore (and later New York City), befriending dogs and taking part in everything from robberies to drug dealing in order to make a living. X felt a particularly strong affinity with stray dogs; animals cruelly forgotten by society, which must persevere in order to survive. And as he graduated from doing DJ sets at parties to actually rapping, X would intimidate his opponents (including an emerging Jay-Z) during rap battles by barking, at eye-level, like a pissed-off pit bull.

By the time his introspective debut album It’s Dark and Hell is Hot dropped on May 12, 1998, X had already been through more trials and tribulations than your average 27-year-old. Yet, this only benefited the listener, with X sounding hungrier than the stray dogs he used to feed in the streets of Yonkers. To millions of people, X, with his warts-and-all honesty, was an artist that felt reassuringly human and down-to-earth.

From Tupac to Cardi B, there are few rap artists who arrive in the mainstream already feeling fully formed, but it was clear Earl “DMX” Simmons was among them. When X barked: “That DMX n***a is a motherfuckin’ problem!” on his debut album’s explosive intro, the whole world felt it. And as the record quickly transitions from street anthems (“Get At Me Dog”) to love songs (“How’s It Going Down”) and dark conceptual confessionals (“Damien”), X showed he could tackle any subject with verve while making you feel his emotions right in the pit of your stomach.

With It’s Dark and Hell is Hot, X wanted to speak directly to the have-nots and reassure them that they were still being represented by a hip-hop culture that had turned into a billion-dollar business built around the gimmicks of shiny suits and silly dances. When he screamed: “Stop being greedy, it’s time to give back to the needy!” it wasn’t an empty phrase, but a wake-up call to a culture which had replaced its altruism for flossy Hype Williams-directed music videos.

Going from one extreme (X chillingly raps: “I fucked you like a chicken with your head cut off” on “X Is Coming”) to the other (X tenderly says “I’ve never felt love like this before” when talking about his relationship with God on “Prayer”), the music on It’s Dark And Hell Is Hot is both ugly and beautiful. DMX feels like a legend come to life; a mythical monster that’s come to free – or, rather sever — hip-hop from its many excesses.

As It’s Dark and Hell is Hot turns 20, Okayplayer spoke in depth to the album’s producer Dame Grease as well as Joaquin “Waah” Dean, the co-founder of Ruff Ryders Entertainment, to assess how this masterpiece changed the course of hip-hop.

Origins

“I knew he was special right from the first time we met,” says Grease, who produced 13 out of 18 of the album’s tracks [other producers included Grease’s protégé Swizz Beatz, P.K. and Irv Gotti] and had a hand in engineering the whole project. He adds: “He literally battled every rapper in New York, and won! X had like six rhyme books filled with verses, where both sides of the pages were rammed with words. People don’t realize X was rapping for a good 10 years before he put out It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot. He really fought to get to the top.”

Subsequently, Grease claims X had become something of a local legend in New York in the early 1990s, with his penchant for aggressively barking during rap battles making him both feared and respected. This reputation quickly caught the attention of Harlem native Joaquin “Waah” Dean, who, inspired by a pep talk from friend and rapper Heavy D, wanted to give up drug dealing for good and find a marquee artist in which to launch his own record label, Ruff Ryders Entertainment, alongside brothers Darrin “Dee” Dean and Chivon Dean.

“We had to get X out of some contracts [by force], as a bunch of people didn’t fulfill their obligations,” Waah tells Okayplayer. “Labels such as Columbia [to which X was previously signed] had no idea what to do with DMX as a commercial artist, but I knew he was a monster from the first time I heard his cassette in the back of my Nissan.” After the deaths of Biggie and Tupac, Waah sensed there was a “void” in hip-hop and a hole that needed filling: “At one point, we were in negotiations with Suge [Knight] and Death Row to sign X, but their contracts made no sense. We knew we had to create our own lane!”

He adds: “In 1997, the music industry was suddenly saturated with all these jiggy songs and the flashy pretty boy flow from Bad Boy and Puffy. I love Puff, but all that did was inspire us to go harder and darker. X comes from a real place and people related to him [more than the ‘shiny suit’ rappers] as there are more people out there who don’t have money than people that do. X was speaking directly to the dude who had nothing in his pocket.”

Built around family and friends, Ruff Ryders was a close-knit crew, with no airs and graces. And, with the help of industry ally Irv Gotti, Waah managed to convince Def Jam executive Lyor Cohen to come up to their Yonkers studio for an early Ruff Ryders session.

“Lyor came over and watched 10 dudes from the streets battle one another,” remembers Grease. “X battled all of them with a broken jaw, yet still won. Lyor said ‘Damn, I’m gonna have to sign everybody in here!’ and that’s how Ruff Ryders got their Def Jam deal.”

The Jump Off

Describing the chaotic environment in which It’s Dark And Hell Is Hot was created, Grease says a typical DMX studio session embodied every aspect — from “good to bad” — of the ghetto. “There were pit bulls fighting outside the booth, people smoking weed, barbers cutting hair. Shit, the dudes selling hot dogs and CDs out in the cold, were probably in there with us too! To some people, this might sound crazy as a recording environment, but it’s the reason X’s music sounded so raw and authentic. We embodied the streets.”

Although there is a loose concept that runs throughout It’s Dark And Hell Is Hot, with skits (such as “The Storm”) featuring people discussing DMX like he’s some sort of horror legend akin to the 1992 movie Candyman, Waah insists the record was “free of gimmicks.” Instead, he says X was trying to communicate “the essence of grittiness.” “At the time, X was in a really dark place as he was in and out of jail. He told me he thought he was in hell mentally and could hear the devil speaking to him. He wanted to find a way to recreate that feeling [on wax].”

But before X could take listeners on this dark journey, he needed a jump-off point. It just so happened he ended up with two—the street anthems “Get At Me Dog” and “Ruff Ryders Anthem” creating the sort of buzz money couldn’t buy. “I produced ‘Get At Me Dog’ to be special. I knew it would create the momentum for the Def Jam deal and X getting to make an album,” says Grease.

The song’s video, which featured footage from a live performance at Manhattan’s infamous The Tunnel nightclub, established X’s rugged street appeal. His constant barking on the track also made it sound genuinely dangerous. “The reason you feel those barks so much is cos’ X really loved dogs. He was an animal lover and would give his life to his dog Boomer before any person,” laughs Waah. “I remember before he started recording those growling ad-libs [on “Get At Me Dog”], he ate dog bones and did all this extra shit in the studio so he could get into character. It created this insane energy on the track. I’m telling you, he really did become a dog!”

Meanwhile, “Ruff Ryders Anthem,” produced by a young Swizz Beatz, was initially rejected by X, who claimed the beat wasn’t raw enough. Yet Waah persuaded X to persevere and the rest is history: “We suddenly had the theme music for our entire movement.”

And that’s not even mentioning “Niggaz Done Started Something,” a classic posse cut featuring The LOX and Ma$e, which dominated New York radio. “That song embodied the whole Ruff Ryders’ energy,” says Dame Grease. “If you come into a basketball court with Lebron or Jordan, you better play the hardest you played in your whole life or they are both going to end your career. With Ruff Ryders’ posse cuts everyone — from ‘Kiss to Sheek to Eve — had to bring their ‘A game’ as they knew X would take glee in killing them.”

DMX during Woodstock ’99 in Saugerties, New York in Saugerties, New York, United States. (Photo by KMazur/WireImage)

The Darkness

Where It’s Dark And Hell Is Hot really establishes itself artistically is in X’s ability to craft intricate yet bold storytelling. While there had been rappers who could rap from multiple perspectives in the past (think Biggie on “Warning”), no one took it as far as X, who contorts his voice to play a whole host of characters.

On “Damien,” which documents an evil presence that tries to tempt X into selling his soul, there’s a lyrical conversation that plays out like the sub-conscience of a madman. Grease’s haunting beat, which has elegant yet twisted live strings reminiscent of Big Star’s Third album, brings out the very best in X. Of “Damien,” Grease remembers: “X already had ‘Damien’ written in his rhyme book before he was signed [to Def Jam]. He just stepped into the booth, heard my beat and did all the voices and verses in one take. It was insane. I know he really wanted to explore the idea of having a split-personality.”

The multiple personalities arguably go one step further on “The Convo” (also produced by Grease), where X has a back-and-forth conversation with God himself. “In rap [at the time] you were just getting one side of a story or situation,” says Grease. “But X gave us all the sides, he was the guy pulling the trigger and also the guy getting shot.” Describing this technique as “three-dimensional”, Grease says “Damien” was a direct influence on Kendrick Lamar and his many references to a metaphorical demonic character called “Lucy” on To Pimp A Butterfly.

X’s trademark conversational stop-and-start flow permeates through the Phil Collins-sampling “I Can Feel It” – a song Grease claims made history: “Up until that point, Phil had never cleared a sample for rappers. This was the first one. Lyor called him personally on his private line and Phil wanted to be assured that the lyrics would be meaningful. Apparently, the minute Phil Collins heard X’s rhymes [on the phone], he was convinced this guy was going to be the next big thing!”

Photo Credit: Mitchell Gerber/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

Success And Legacy

Phil Collins had a point: It’s Dark And Hell Is Hot went onto sell over five million copies, with X becoming the first rapper to release two platinum albums in the same year, having gone on to drop multi-platinum Flesh of My Flesh, Blood of My Blood in the fourth quarter of 1998. Whereas X once walked the streets with barely a penny to his name, by 1999 he was performing to 400,000 people at Woodstock, who were forming mosh pits and passionately rhyming along to every single word. It felt like a future G.O.A.T contender had arrived.

On It’s Dark and Hell is Hot’s intro, X raps hopefully about the future: “Girls give me head for free cause they see/Who I’ma be, by like 2003.” The reality is X didn’t need five years to take over the world. Reflecting on the record’s huge impact, Waah, who is currently trying to reignite Ruff Ryders as a label with a slew of new artists, says: “It was the realest thing to ever hit the streets. We changed the whole Richter scale of hip-hop as X was someone everybody could relate to. We represented the people who didn’t have a dime and that’s why we sold 10 million records in just one year.”

He boasts: “Every song on that first joint could have been a single. X could write a hook for a hit single without even thinking.”

The fact X could get 400,000 white kids losing their shit at Woodstock was proof he was hip-hop’s first true rock star, according to Grease. “Biggie was all about getting money and being fly, and ‘Pac was more of a revolutionary movement. But no one talked to every single person like X. X couldn’t be media trained, he was just a rock star like Kurt Cobain, who did what he felt.”

The album’s horrorcore elements (On “X Is Coming,” X graphically threatens to rape an enemy’s 15-year-old daughter), which see X playfully invent new ways to murder someone, also freed up artists such as Eminem to instill similarly dark cinematic themes on their own major label albums, according to Grease. He compares the emergence of X and It’s Dark and Hell is Hot to Nirvana and “Smells Like Teen Spirit” dropping seven years earlier in 1991.

“Pop music became a parody of itself in the eighties and then Nirvana came and brought the raw back,” he explains. “X was the hip-hop equivalent of Nirvana as he was the antithesis to the more pop-friendly direction rap music had moved into. The ‘Shiny Suits’-era was dope as fuck, but millions of people were craving something more real and X was the only one brave enough to take them there.”

It’s more than fair to say critics routinely dismiss the monumental impact X made on hip-hop culture, and the fact his discography is littered with classics. Instead, DMX is now portrayed as a tragic figure, who is more associated with controversy (FYI: X is currently serving prison time for tax evasion) and substance abuse. However, Waah says the media loves to belittle X’s musical legacy, simply because they hate the fact he can’t be controlled.

He concludes: “He gets downsized as the industry only glorifies the artists they can control. No one can control X and they hate that X is a true artist from the community and the street. He won’t sell out for anything and that pisses people [in the industry] off. Look, eventually, people will start to realize DMX is a one-off. An artist like that only comes around once every 50 years.”

This story was originally published in 2018.

__

Thomas Hobbs is a freelance culture and music journalist from the UK. His work has appeared in the Guardian, VICE, Financial Times, Dazed, Pitchfork, New Statesman, Little White Lies, The i and Time Out. You can find him on Twitter: @thobbsjourno.