Art via Evan Solano

If you value independent journalism, please subscribe to the POW Patreon.

Slime-colored bandannas in front of the flag, wolves clutching draco’s, ecclesiastical orchestrations, drums exploding into shrapnel, siren-like drones, halcyon memories becoming increasingly unfamiliar, Max Roach vocals, coke rap at the Vatican, ayahuasca trance, broken phones, cyberpunk, and living, laughing, and loving. It was 2025.

Sold out arenas across the country. Each stop a pulsing, rocking, sea of glowing neon green. Tens of thousands of fans—blurring together under sheisties, leather pants, black Air Forces or Balenciaga track runners, and slime-colored bandanas—stamping, jumping, sometimes crying. YoungBoy Never Broke Again’s MASA is a sprawling, 30-song burst of raw energy that falls short of the Baton Rouge cult hero’s best work. But taken as a phenomenon, what with its accompanying hundred-million-dollar tour and intermittent release from at-home electronic monitoring, it’s one of the signature events in rap this decade. Even those box-office receipts fail to capture just how dense his gravity is; YoungBoy is his own solar system. – Dario McCarty

Safe Mind’s debut is twinged with a desperation to connect, which makes sense for a record whose roots stretch back to 2020, when Augustus Muller—of the electronic duo Boy Harsher—tapped Cooper B. Handy (LUCY) as a collaborator on the gothwave band’s 2020 track “Autonomy.” Together, Safe Mind’s lyrics skew blunt but optimistic; the production grounds the project in blissful bangers like the refreshing euphoria of “Standing on Air.” The apex is the eclectic “6’ Pole,” where grungy vocals from Handy grind against slinky, sizzling guitar riffs, embellishing the blunt-force squelch of a mid-chorus synth stab that calls to mind the staccato barks of a friend’s “really friendly” German Shepherd. Cutting the Stone embraces both the stark shadows and jolts of light of a dancefloor, the renewable resources of tears and sweat. – Staley Sharples

If Zukenee didn’t rap about Dungeons & Dragons or cosplay as a wolf holding a draco, SLAYTANIC might pass for something unearthed from 2014. It’s soaked in the amniotic fluid of trap’s golden age; what makes it 2025 is the absurdist flair and self-mythologizing. Songs like “Cut Ya hand” and “Hindu” sound as if they were recorded by candlelight in a torture chamber, a blood ritual taking place down the hall. Zukenee compares street politics to medieval warfare, dotting his verses in stridently theatrical imagery. Instead of mimicking trends, he warps familiar conventions into an eccentric, playful album that consistently surprises you with its strange, singular vision. – Diego Tapia

Acopia’s third LP, Blush Repose, is like that first night of sober sleep after an extended binge. The cobwebs remain, but each second of uninterrupted rest brings a sense of clarity. It’s a sharp detour from their self-titled sophomore effort, as the band trades in aggressively stripped back arrangements for something fuller, more tangible, and satisfying. The magic of Blush Repose is in the way this clarity and precision remains razor sharp as the palette adds color. A lot of this weight is carried by vocalist Kate Durman, who has a unique ability to convey feeling via a whisper, an aside, a seemingly innocuous observation. Often, she obsesses over the opposite of nostalgia. These aren’t moments she wants to revisit, but fix or piece together in a different way. Alas, stitching together the past is like glueing back together a vase that’s shattered into thousands of pieces. She captures the surreality of a breakup with startling acuity on “See You In Everyone”: “Can’t believe that you’re gone/It’s the strangest thing I ever felt/But it feels like you never left/’Cause I see you in everyone.” There’s no anger in her voice, just regret that sits and festers. It doesn’t go away, until one day the hangover is gone. – Will Schube

Popular music’s always had a concerning relationship with death. Mass Appeal’s Legend Has It series this year offered late-career albums from Slick Rick, Raekwon, Ghostface, and Nas and DJ Premier, but also posthumous or quasi-posthumous ones from De La Soul, Big L, and Mobb Deep. These are not long-lost, finished recordings finally seeing release; they’re newly assembled from otherwise unused vocals. A deflating proposition. And yet here we are. From the subtle melancholy of “Against The World” and the lofi psychedelica of “Gunfire”— to Hav an P improbably still weaving in and out of one other’s verses on “Mr. Magik”—Infinite sounds like a real Mobb Deep album. A genuine slice of Queensbridge grime that might actually be their best body of work since Murda Muzik. This is in large part due to P himself, who in his final years oozed the confidence of a man wholly content with who and where he was. “I lived a full life, don’t cry for me,” he raps on “Pour The Henny.” Amen. – Jaap van der Doelen

With success comes strife. While El Cousteau’s uniquely animated style has long made him an idiosyncratic presence within the flourishing DMV rap scene, the DC native seems to be at a career crossroads, one direction leading to immortality, the other casting him as a brief viral spell. Dirty Harry 2 takes pains to detail the sacrifices it took for him to arrive here, balanced by metareflections on how he’s been perceived throughout his career. On “Cause & Effect,” Cousteau fires back at faceless critics: “You think I wasn’t paying attention to the fake interest and the side eyes? Telling me my personality too far-fetched and I’m a wild card.” “My career right now don’t give me the capacity to love my mother like I’m supposed to,” he laments on “Pico,” the crown looking awfully, regrettably heavy. – Josh Svetz

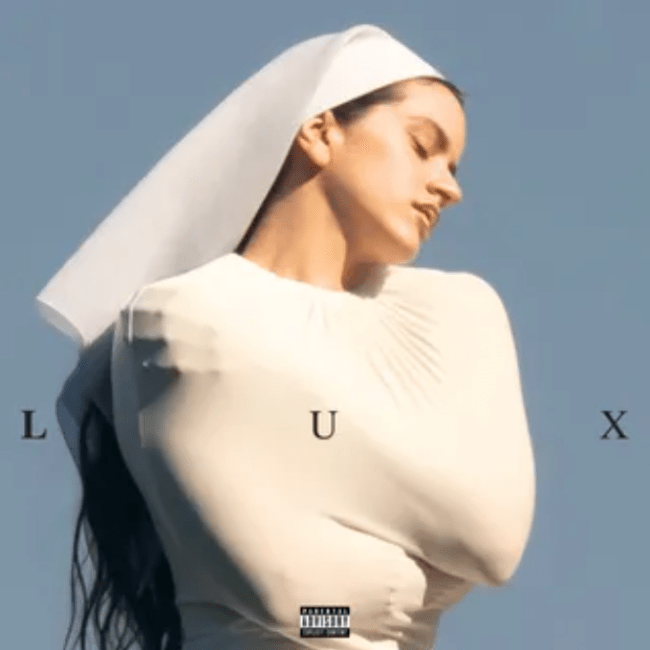

Rosalía’s fourth album is opulent, ambitious, and unfolds like a divine incantation—a benediction for the heartbroken, an exploration of feminine mystique, a battle cry for the transcendence of the personal.

LUX is an ecclesiastical, operatic lament driven by thunderous basslines, strings performed by the London Symphony Orchestra that are at turns classical and warped, pounding synths, a maelstrom of textured layered with transfixing vocals and sung across 13 languages. It’s a deeply personal work yet confrontational maximalist. Divided into four movements, each song is conceptualised around a female poet, mystic, heroine, prophetess, or saint. The featured artists themselves are an array of living deities: Björk, Patti Smith, renowned Portuguese fado singer Carminho, and Yahritza, a rising Mexican star in the regional genre of urban sierreño, to name a few.

On “La Perla,” Rosalía calls out her ex-fiancé over a saccharine melody: “Hello, peace thief,” later describing her villain as a “local fiasco, national heartbreaker, emotional terrorist, world-class fuck-up,” a “walking red flag,” and an “absolute drag,” illuminating the idea that men may fail you, but God never will. Rosalía has found faith and light in LUX, and she commands listeners to follow. – Tracy Kawalik

The newest member of the Stinc Team is finding a rhythm. On “Free Da Homies,” one of the standout cuts from Product Of The Trenches, Day3 breathes new life into the “Crank That” steel drum patch that Souljaboy made famous on brick phone ringtones almost two decades ago. But here, the stripped-down L.A. hi-hats dust Exorcist-coded piano notes that fade into an echo as he commemorates confidants and champions his section of the 60s.

Part of this album’s charm are the rough corners and the different mixes, like the blown out 808s on “GrandPedro Gang – REMIX,” instantly transporting you into an overpacked car with a bleeding stereo system. Other songs, like “Throw It,” and “To The Party,” are club speaker crisp. For Day3, its clear leaning into his versatility will remain key to pushing the sound forward in a post-Drakeo world. – Evan Gabriel

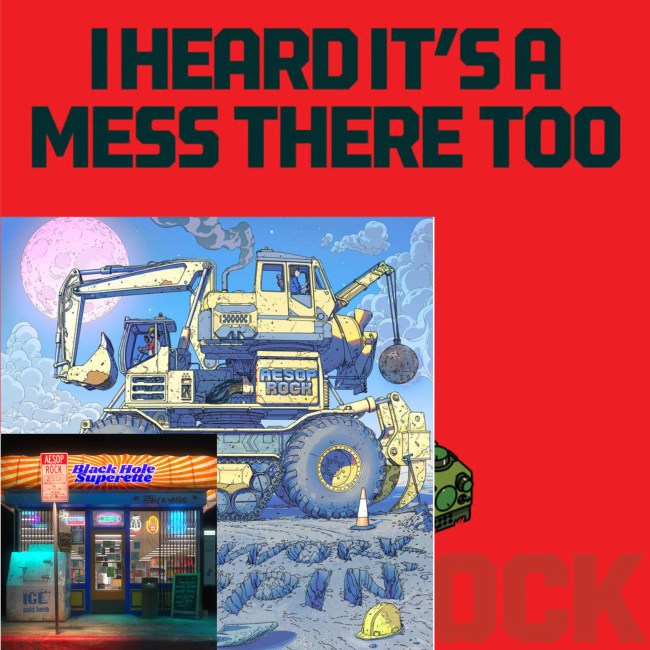

While Aesop Rock handled production duties on May’s Black Hole Superette and October’s I Heard It’s a Mess There, Too, as he largely has since 2003’s Bazooka Tooth, the two projects have distinctly different sounds and feels. BHS is closer to what fans have come to expect: densely layered beats filled to the brim with Aes’s vocals, a cacophonous rush. The album also sports a murderer’s row of underground stalwarts, including Armand Hammer (“1010 Wins”), Open Mike Eagle (“So Be It”), Homeboy Sandman & Lupe Fiasco (“Charlie Horse”) and Hanni El Khatib (“Unbelievable Shenanigans”). The veteran of three decades continues to blast past the Simpsons Already Did It test, covering topics I’m very comfortable claiming without further research have never been covered by anyone before, from the respect he feels for a bladder snail infestation in his girlfriend’s new fish tank (“Snail Zero”) to the magic of watching a flock of hundreds of swifts (the bird, not the Taylor) descend upon a local chimney annually (“Bird School”).

I Heard is much leaner in both the macro and micro, centering Aes’s lyrical delivery, though the topics are no less esoteric. It’s an attempt to process a world in disarray, the album still manages to take potentially downer material and make it swing. According to the man, “It’s about observation and communication. Sonically, I wanted a reset—cleaner beats, more space, fewer layers. Just enough to get a wave rolling and not much more.” Mission accomplished. – Chris Daly

Perhaps the most interesting feature of techno (specifically the Detroit school), both sonically and politically, is the poignancy in which it speaks about the human body’s relationship with technology and with the idea of The Future; it’s precisely why Romance in the Age of Adaptive Feedback feels both timeless and timely. The debut record by the project headed by Louis Digital uses the language and methodologies of the classic black American styles to bring forward its radical ideas to challenge the algorithmic now. Undoubtedly, its greatest quality is that, even when it’s indeed romantic and vulnerable, it never surrenders to nostalgia; its grainy textures and obscure haunted city soundscapes are masterfully interwoven with the funk roots, resulting in a work that reclaims the spirit of liberation and hope that has been slowly stolen from us. – Leonel

Eliana Glass is interested in ghosts. In an interview earlier this year, the New York singer-songwriter put it plainly: “I love that all these other people live in me.” At its best, E, her remarkable debut LP, is the sound of familial and musical histories alike cast into the darkness. E is haunted, somewhere between mid-’50s vocal jazz and contemporary singer-songwriter material, plus the grace of a warped Ella 45”, with negative space to spare. It is built upon melodies that turn intuitive in retrospect and a sound that is frequently made of just (“just”) piano, voice, and a rhythm section. But few things are ever that simple: tilt your head right and you’ll find entire histories. Glass’s compositions here—collages of love and loss and joy—are both minimal and kaleidoscopic, often encapsulating entire lives in the span of a few minutes. Ultimately, E is a seance: if you knew spectres were listening, it asks, what would you say to them? – Michael McKinney

In the fourth year of Fatboi Sharif’s excavation of our most atavistic horrors, he unearthed no fewer than three darkholds written in the ink of three covenmates. First, the scream on all our lips, Let Me Out, which you shall know by the trail of the Driveby. Second, ENDOCRINE, with GDP-manipulating crypto beatcoin exchanges and ouija predictive markets. Finally, Goth Girl on the Enterprise, with photon torpedoes fired by Roper Williams at the helm.

Long lost in the scroll of the artificial stupidity Nazi psyop formerly known as Twitter, Sharif gave us a rare glimpse inside: “I’ll never forget the way I felt hearing Outkast’s “E.T.” for the first time as a kid riding thru South Carolina in a thunderstorm. I constantly aim for that when I create.”

Fatboi Sharif is indeed the Outcast Extraterrestrial, the Panspermian Pennywise, the Gore Auteur, the Phantom of the Gas Station, the Disk Jockey Pornographic Cybernetic Organism.

All that evil buried beneath Amerikkka’s substrate has gushed forth. Here is the bone roller, the Dread Psychopomp, who palpates entrails at the pulpit. Rituals of ignorance and nausea deep in the Pine Barrens. Uncurling centipede, carapace crackle. Bugs Bunny foaming at the mouth from myxomatosis. 9/11 simulation in a Roblox environment. The luchador mask smells like sriracha and monkey meat, take a sniff. The Rahway Nyarlathotep has risen from the swamp, all hail. – Elmattic

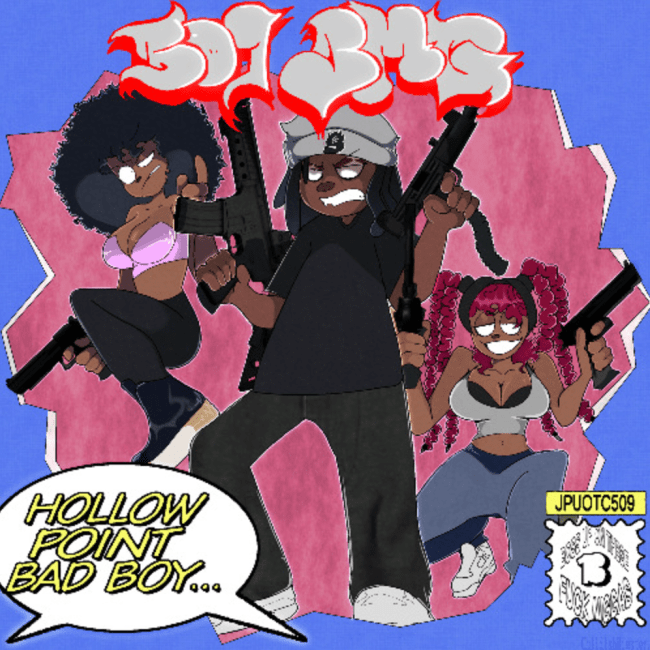

There’s a world in which Miami’s 509 BMG became a stadium-level stand-up instead of one of the most promising young rappers in Florida. His formula on Hollow Point Bad Boy is simple: find a beat that floats, then lasso it back down to earth with his punchlines. He raps like he splits his attention between obscure games on NBA League Pass and whatever the equivalent of Something Awful is for zoomers. Over the course of a song, he’ll compare himself to Isaiah Stewart, then threaten to kill somebody like Phil Spector, accuse somebody’s boyfriend of breadcrumbing, then proclaim himself to be such a hater that you’d think he’s a Republican. He first came to the internet’s attention with his track “Special Request to All Nice and Decent Real Ni—az (Stop Hatin),” an 11-minute odyssey of beat-hopping absurdism, in which he tore through one stoned-ass 80s dub instrumental after another. That track doesn’t show up here; instead, he favors the same chintzy, Zaytovenesque instrumentals once used by the immortal Metro Zu. Thankfully, there does not yet exist a prediction market for abstractions such as “this dude’s gonna blow up,” but if there were, I would buy the shit out of 509 BMG stock. – Drew Millard

Across three recording sessions from 2021 to 2024 at the house of underground rap producer Kenny Segal, Human Error Club—the brainchild of keyboardists Diego Gaeta and Jesse Justice along with drummer Mekala Session—recorded over ten hours of their signature free-spirited and improvisational nu-jazz, which Segal distills into the potent 39-minute runtime of Human Error Club At Kenny’s House. A product of the post-Low End Theory L.A. beat scene, this is music that long ago dispensed with genre borders. Influences including hip-hop, electronica, funk and krautrock are transmuted into a more formless fusion jazz of the future.

The first few tracks lean towards a fuzzier, ambient sound that toys with 64-bit nostalgia. The backend goes maximal and abstract, producing the sort of astral haze from which one might divine cosmic truths. The album’s closer-before-the-closer, “THE CENTER,” is a seven-minute vision quest through the Earth’s core, featuring oracular passages from poet-musician-activist Moor Mother on sun gods and the ruinous tide of late-stage capitalism. This is Human Error Club’s first release under billy woods’ Backwoodz Studioz and brings in guests from rap’s modern-day underground for verses that blur the lines of genre convention even further; it’s a delight to hear voices like Quelle Chris and Pink Siifu brush against this more psychedelic backdrop. Experimental energies fly fast and loose on this album, a testament to the particular alchemy of a few obsessive, omnivorous music nerds jamming in one room for hours on end. – Kevin Yeung

The breakout album by Baton Rouge duo 70th Street Carlos and WNC WhopBeezy is as infectious as bubonic plague. The repetition of the chorus on “Fall In Line” sounds like a wide receiver coach having a spat with the star player for not working hard enough at practice; “DYS” is what “tv off” thinks it is, an HBCU parking lot-turned-Terrordome rather than a Nike commercial. Out The Blue is also a nexus point for Louisiana rap history: the bass lines that feel born from the streets of Gardere, the drums beholden to BG’s blockbusters represent whole worldviews, not just unexplored corners of ProTools. It makes sense: Carlos and Beezy came out with this album after years of sitting idle, seeing stars like Youngboy and JayDaYoungan take off before they did. They paid their dues. – Jayson Buford

Bruiser Wolf’s mic presence falls somewhere between preacher, pimp, and standup comedian. Those qualities coalesce into an inimitable—if polarizing—package on POTLUCK. Like him or not, you’re not going to forget the Bruiser Wolf experience. On his third album, the Detroit rapper is not just funny, but a dexterous writer and spitter who can get off over a variety of beats. There’s the Pee Wee Herman sample on the song of the same name, beat switches on “Air Fryer” and “Baby you,” as well as “Beat The Charge,” where Nicholas Craven flips a glorious soul sample (that we surely won’t be revealing).

The Detroit rapper has barbs coming from all angles: On “Write or Wrong” he raps, “Bought Ritalin for my white-chocolate and vanilla friends/Bucket hat like Gilligan, fuck cancer, stay away from carcinogens,” chaining multi-syllabic non-sequiturs with an unexpected nod to the late actor Bob Denver, who died of cancer. But he’s also telling stories, such as on “Offer Couldn’t Refuse” and “Trust Issues,” where he raps about his past life in the streets. It’s dense, and as a listener, you have to work to keep up. While you’re laughing, scratching your head, and trying to peel back the layers of reference, he’s unfurling more hilarious bars. – Andre Gee

For half a decade, Daniel Lopatin had been pursuing increasingly inward circles. In 2021, he released an album re-envisioning his own discography through an FM-radio lens, then on Again looped in on himself tighter, creating an “illogical period piece” about the music of his earlier adulthood. On Tranquilizer he makes a different kind of return, not conceptually but rather to the way he made music fifteen years earlier: plundering vast archives of discarded sample libraries and rompers and flitting between them to part-compose, part conjure new songs from whatever accidental magic he encountered there.

As is the beauty of Lopatin’s music, this context is both enriching for the album and utterly unnecessary to appreciate its scale and beauty; a disembodied sound-world which scrapes the passé textures of lost, late-90s composers and creates twinkling mirages out of them. It’s his most direct music in years. Playful, sometimes eerie, but often achingly poignant. We get Lopatin at his Frankenstein best, taking a trowel to the internet graveyard and breathing life into dead, orphaned vestiges of sound. – Liam Inscoe-Jones

Spend too much time in extremely-online dance music circles, and you might be led to believe that the party is over, having collapsed into a catastrophic comedown. In this nightmarish dystopia, enraged leftist clubbers preen and rant, achieving nothing, while festivals get swallowed whole by Private Equity firms determined to extract every cent of value from the impotent husk of rave. Thankfully, Surgeon has the remedy: 47 minutes of banging, one-take improvisational Techno heavy enough to rattle your fillings, a perfect reminder that dance music can only unite us if we actually dance.

Recorded live on a Pulsar-23 drum machine and Lyra-8 synth, with a bit of delay for good dubby measure, Shell~Wave is a rarity in electronic music: a virtuoso demonstrating mastery over his instruments. In less judicious hands, that could have gone terribly wrong – no one wants Techno’s answer to prog’s bloat. Thankfully, Surgeon deploys his 30-plus years of experience as a DJ and producer to keep things lean, mean and functional, with Post-Punk’s noise, Detroit’s pulse and Jamaica’s bass & Space as his north stars. Drums explode into shrapnel, textures crumble to dust and the rest sounds like broken machinery on a particularly demanding exercise regimen. In short, it’s fucking Techno m8, and it’s a good deal more interesting than your latest think piece about the scene. – Son Raw

“I’m the best dressed n—- on my therapist’s couch,” Mavi boasts with the cheeky confidence of someone who’s cracked the code on stability. That opening line on The Pilot—a prelude to upcoming concept album First in Flight—is a summation of what to expect from the North Carolina MC on this go-round. For now, the subdued, self-deprecating confessionals that defined previous works make way for braggadocious boasts about custom Cuban links, Cartier watches, and “seeing a hundred racks flow through a money counter.”

Much has been made of Mavi’s year-long sobriety—head-nodding highlight “31 Days” has him marking a month without ingesting substances—but it’s merely one element in a complex healing process. Long-time admirers of the diaristic writing on his previous records might bristle at this latest thematic pivot, but why shouldn’t Mavi flex about being in a better place at this point in his ascendant career? “I don’t weep, I just earn” is a mantra he repeats throughout “Silent Film”, a bouncy number that also has him admitting that he “made a million off [his] grief.” The Pilot isn’t a complete abandonment of his usual vulnerability, but rather a showcase of how health and wealth are almost symbiotic in the quest for never-ending personal growth. – Oumar Saleh

Jay Worthy is always cool, calm, and collected. Typically locking in with a single producer or fellow rapper on projects (2 P’z In A Pod with Larry June, the Harry Fraud-assisted You Take the Credit, We’ll Take the Check, Nothing Bigger Than The Program with Roc Marciano, etc.), the Vancouver-born, Compton-raised rapper captures the West Coast breeze and inner workings of the luxurious mafioso lifestyle through his lived-in raps.

For this year’s two-disc Once Upon A Time series, he corrals a wide cast of collaborators—Cardo Got Wings and DJ Quik, Conductor Williams and 03 Greedo, Conway the Machine, Ty Dolla $ign––who help yield Worthy’s most balanced and varied effort to date. He consistently settles into a bouncy cadence, delivering the kind of effortless raps that make his improbable come-up seem inevitable. It’s a potent combination of slick talk and sentimental reflections. – Isaac Fontes

Sequels warrant skepticism. That’s been the case since Louisa May Alcott ran it back by popular demand, but it’s worse than ever in the current content churn. Sequels pushed out as TITLE 2 feel extra cynical—at least show us some dignity with a pun or a few words after a semicolon. We were subjected to a lot of lazy retreads in 2025. Happy Gilmore 2 was a cash grab with its pharmacy receipt of a cameo call sheet. The Accountant 2 was ritual humiliation for Ben Affleck (Ben Affleck 2). In lesser hands, Alfredo 2 would’ve been a laminated SEO play off of Freddie Gibbs and Alchemist’s 2020 success. But here the duo deliver inspired work from a vat of butter cream and Parmesan. “1995” extends the WWE-walkout guitar wails from the first album’s intro; “A Thousand Mountains” transports with lute flutters. And “Gas Station Sushi” decelerates off counter-clockwise snare clicks. Alchemist beats upholster the floor of any project, but Gibbs meets the moment as an emcee. He’s still got jokes—Tee Morant punchlines for his young shooters and “titty-twisters” for DJ Akademiks. His surly candor is more exposed as a quadragenarian, though. Cold-sweat nightmares drift from Gary to Shibouya during “Ensalada,” and cigar-smoke shit-talk reheats beef from Buffalo to the Biscayne on “Empanadas.” The whole back half carries a winking disgust for IG model baby showers and FanDuel prop bets. Alfredo 2 wins as earnest output with clear purpose. Here’s to more of that next year (working title: 2025 2). – Steven Louis

When Rhys Langston was 15 he was told he might never play basketball again. The L.A. native—an aspiring ballplayer who had forced himself to play through some minor injuries at the behest of his father and coaches—had torn multiple ligaments and broken off the top of his tibia bone. Gruesome Shaun Livingston-type shit. Decades after a full recovery, Langston invited his father to voice “an absurdist Bobby Knight” caricature on “Pale Black Negative.” It was a moment Langston told us allowed them to laugh at basketball while working through the hard emotions that still lingered from that day.

Pale Black Negative is the 20th musical project to be transmitted from the shores of Langstónia, and the most intimate the polymath has ever been on the mic. Beyond the touching work on the titular track, Langston pays reverent tribute to his cousin Moziah (“Chancla Gander (a Spiritual for Moziah)”), details the twisted nature of the comfort that can accompany depressive episodes in sing-song fashion (“When I’m Squared With Happiness”), and stitches together clips of friends talking about their hair over banjo licks (“It Jes Grew (Right Outta Me)”). The care and love infused into Pale Black Negative renders the work one of Langston’s finest. Oh, and he can still dunk on you. – Kevin Crandall

Sudan Archives has always liked to incorporate a little bit of everything in her music, in all forms of seemingly incongruous combinations: Irish fiddles and Jersey-club kickdrums, Detroit techno and West African instruments, classical violin soundscapes with screaming rave-raps. Since her first Stones Throw releases in 2017, nothing the Midwest-born Brittany Parks has put out has been conventional, and her sonic shifts from EP to EP to album to album have never been predictable. When she decided to take it all to the club this year for The BPM, her inspiration was as discordant as you might imagine: the aftermath of a disintegrating early-decade relationship with All City Jimmy, and a subsequent desire to just dance. “I’m trying to get out all the jitters,” Sudan Archives told Hearing Things in October. “I’m lit. I can be stupid if I want to be. I’m not your magic little violin player.”

The BPM, her third LP, gets it all out there: Prince-style computer-love aesthetics, percussion just loud enough for a strobe-light-heavy nightclub, rhythms and arrangements that flash in and out of focus, measure by measure. The opener, “DEAD,” features an orchestra that gives way to jungle production before a thrilling climax bumps them all up in volume. “MS. PAC MAN” almost sounds like it’ll go off the skids any minute, before Sudan Archives anchors down the chorus with an irresistible chant (“Put it in my mouth/ then my bank account”). Throughout the record, familiar, quotidian sounds like police sirens and iPhone swooshes find their way into the mixes, dangling reminders of the real world over our nightlife-addled heads. As The BPM goes on, there’s a wispy, airy melancholy that suffuses the environs, eventually taking us off the dancefloor and back into Parks’ most wistful thoughts (“I’mma need all of y’all to leave right now/ I’m done with people-pleasing so I’m mean right now”). Once we reach the conclusion in “HEAVEN KNOWS,” the most straightforward track on the album, the party’s over, and heartache has come to accompany the hangover. But hey, it was a blast along the way. – Nitish Pahwa

The Oxford-raised DjRUM has always been difficult to neatly pigeonhole into one genre. Combining sparkly deep house synths with a downward spiral violin arrangement, which sounds like a mother crying out for her lost son, the 2018 song “Blue Violet” reflected an artist who clearly got just as much thrill from igniting jungle raves as he did prompting some delicate, ambient-triggered soul searching.

With 2025’s Under Tangled Silence, we are treated to an artist who has found firm footing. Mixing up the sharp edges of techno with thrumming percussion, DjRUM spends a lot of this project manipulating live harp and piano melodies. Through the process of tangling up all those crossed wires, he concocts something genuinely alien. “L’Ancienne” is a great example of this, with elemental piano jazz keys falling like a gentle rain melt into a cacophony of drums and siren-like drones.

This zig-zagging, yin and yang effect, was confirmed in an interview with Bandcamp’s Sam Davies, where DjRUm stated of the album’s creation: “I was in a particularly…tangled, confused emotional state. My mental health is up and down, I guess like many of us.” Thankfully, the artist knows when to break free from heavy emotions, with the Wipeout-esque, turbo-charged kick drums of “Let Me” and its mischievous, unfurling, gabber-referencing synth-line as free as a dog let off its leash at a beach. – Thomas Hobbs

Long before my screen time began to approach the number of hours I spend awake, the digital world had lost its luster. “Endless scroll” doesn’t just describe our social media feeds, but the entire experience of being online in this era—in which we are induced to cycle between self-promotion apps that have monopolized our imagination for what constitutes a life well lived. Arriving in that context, an album called I Love My Computer scans, initially, as sarcasm. Nina Wilson, however, means it with full sincerity. The 26-year-old Australian producer’s debut album takes us back to a more winsome period of digital possibility, recreating proto-EDM beats that gleam in 1080p and thrum like a middle school crush. Every song is a finely-rendered marvel of 2000s romanticism, tapping back into halcyon memories that are increasingly unfamiliar: a time of software-mediated self-discovery, “surfing” the web, and feeling seen rather than watched by your computer. – Pranav Trewn

I open my phone. I see: a cat whose laryngeal paralysis makes him meow like Barry White; an AI-generated remix of a Marvel climax starring Charlie Kirk as Captain America and Diddy as Black Panther; an advertisement enticing me to gamble on the possibility of a recession; dismembered children; pornography; a mashup of the AI Charlie Kirk song and Mariah Carey’s “All I Want For Christmas Is You”; starving children; Sydney Sweeney. Each image fragment and sonic byte is immediately replaced by the next. I’m tempted to say they wash off me like water does a duck, but that would be dishonest. A residue calcifies in my brain and my heart. I am acutely distracted and ambiently enraged.

Jane Remover’s Revengeseekerz doesn’t emulate the experience of scrolling—why would you want your art to do that?—as much as it meets your mind where it regrettably is. The high-water mark of the Internet-cum-underground’s most ambitious and influential forerunner is a synthesis of Jane’s sharpest instincts over the course of twelve breakneck dispatches. At one moment, Jane evokes Hannah Montana produced by mohawk-era Skrillex; in the next, you’re disarmed by a hoodie-sleeves-over-wrists emo melody that you never thought you’d hear outside of a Geocities site. Where most of their contemporaries have at most one great pop song lying dormant within them, Jane picks apart their own for samples and scraps. Here is a temper tantrum as record, a mission statement from an artist who zips from idea to idea not because they’ve run them dry but because they’re bored, jittery, web-addled, and burning. It’s a marathon, sprinted. – Ock Sportello

It’s doubtful this was the intent, but Fada<3of> serves as a highly effective survey of the most interesting throughlines in rap music today. Niontay hails from MIKE’s 10k label bloodline and has clearly internalized his labelmates’ bias towards mumbling scratchiness, and at various other moments here Niontay channels twitching New Jazz synths, the distant echoes of frame-rattling Miami bass, plugg chirps, and late 2010s Lucki. But while most of rap music drifts ever closer to letting the playlist and the album fall into total eclipse, Niontay suggests that even a seemingly scattered approach can coalesce into something consonant if the individual is this uncompromising. Fada sounds like tumbling down some endless pit for forty-five minutes, Niontay’s slurred voice echoing off the walls to chase you ever downwards in free-fall. I am reminded of the first time I ever heard Kodak Black’s “No Flocking” and the friend who showed me asked what genre of rap I thought I was listening to. My only thought was that it seemed like the wrong question.

The stop-start nature of the album, nineteen songs over those forty-five minutes, only adds to the effect. There’s a rough-edged nature to the songs, but with closer examination it’s less that the songs are incomplete and more that they are almost all structured the same way to radiate out from one central concept. And if a song is just a concept, there is basically no bounds on what a concept might be, including a five-second cadence—like on a song like “Vice grip”, where Niontay basically pounds one flow into the dirt for 3 straight minutes like a glitchy GIF twitching through its frames. Taken as a whole, it actually feels like Fada’s constantly shifting tonality is actually an act of charity towards the listener: otherwise, Niontay’s endless stream of consciousness might be totally suffocating. To summon this level of single-mindedness in their work while still accommodating all their creative whims puts Niontay in a class of his own today. – Sun-Ui Yum

In 2025, R&B left behind its moody, Drake-inspired lullabies for familiar flavors of the late aughts. However, where artists rosily looked back on the kind of records Bryan-Michael Cox and Johnta Austin used to pen, the futuristic sounds and colors that defined the recession era were ignored. hooke’s law by Chicago’s KeiyaA is a gorgeous take on that underrated time in R&B. Sure, there’s the grandiose framing and digitized synths akin to Kanye’s 808s & Heartbreak, but dig into her sputtering spoken word and autotuned croons, you’ll find a lot more history to chew on.

Take the feverishly horny “think about it/what u think?” and “k.i.s.s.” as modern expansions of Kelly Rowland’s sexy “Motivation.” “until we meet again” is an existential crisis through the cyberpunk pinks and blues songs like Jamie Foxx’s “Digital Girl” used. KeiyaA’s vocal delivery curbs from Rapper Ternt Sanga era T-Pain just as much as Jill Scott. Our new recession era R&B still channels that same futuristic aesthetic but we don’t have that Obama-era hope to suckle on. Instead, hooke’s law grapples with a lot more anxiety and contempt for landlords. – Caleb Catlin

For the sequel to their titanic 2021 collaboration Haram, the world’s greatest rap duo and its greatest rap producer turn inward from the skybound climax of Haram album closer “Stonefruit.” billy woods—rightly regarded as one of America’s great contemporary writers in any medium—still inspires dissertations from music critics and garners comparisons to Flannery O’Connor and George Saunders rather than anyone in the practice of rap music. ELUCID continues to rap much like Max Roach played drums, in terms of both precise rhythm and otherworldly soul. Alchemist goes from experimenting with sound on his first AH collab to tinkering with meter and creating what might be his richest full-length set when it comes to melody.

While Alchemist adds to his minor-key mastery, he also conjures up maximalist jazz-disco (“Longjohns,” featuring an inspired verse from Quelle Chris), psychedelic soul (the Earl Sweatshirt-assisted Hayesian epic “California Games”), a keyboard line that sounds like it could have been lifted from The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past (the aptly-titled “Super Nintendo”), and even a little downtempo trip-hop mastery (“No Grabba”).

ELUCID and woods, to their credit, are far too slippery for their lyrical themes to be pinned down and placed neatly in a box. Here, they cover aging athletes past their prime, nostalgia warped by the harsh light of hindsight, poetry’s role in the misinformation/AI age, violence (whether corporeal, emotional, or state-assisted) as ambient background noise, and eviscerated bodies filling human landfills. The feel-good hit of a feel-good year. If mercy is a theme at all on Mercy, it’s certainly not God’s mercy woods and ELUCID are rhyming about. – Douglas Martin

You’d have to go way back—like, “Go shorty, it’s your birthday” back—to find an opening line that burrowed into the culture as instantly as “My name is Pink and I’m really glad to meet you.” The narrator’s introduction on “Illegal” is accompanied by the synth melody from Underworld’s 1994 classic “Dark & Long (Dark Train Mix),” beaming across time and space from Renton’s locked bedroom in Trainspotting. Yesterday’s rave music is suddenly today’s TikTok meme.

That manic energy is sustained across Fancy That‘s breezy 20-minute runtime, as impeccably chosen instrumental samples (Basement Jaxx, Groove Armada), melodic interpolations (Just Jack, William Orbit), and random YouTube vocal snippets are smashed together at maximum velocity.

Pink’s playful songwriting elevates the material beyond rote pastiche. The subject matter is standard pop fare—love, lust, introspection—but her lyrics are charmingly clever and intimately conversational, and each line (even the casual asides) is lab tested to be as viral as the choruses. Every song here is good enough to be a single, and every single (especially “Stateside” and “Stars”) demands heavy rotation. – Pete Hunt

Two decades ago the Thornton brothers rapped about being children: “See, in my household it was quite unique/Playing hide and seek you might find a key.”

Underneath the coke tools and the vocal equivalent of spooky, unbroken eye contact, Clipse’s Lord Willin’ was rich with familial ties.

Clipse’s next 20 years had no home games. The sophomore album was forever delayed. We settled for two best-in-era mixtapes. Then that long-awaited second album, Hell Hath No Fury, becomes a classic. Malice goes solo, disavows his previous work and explores Christian rap. Pusha T’s solo work elevates him to living legend. He becomes haute couture’s favorite coke rapper, his songs humiliating pop stars years before a Pulitzer winner would.

Then, after only rumors in 2024, Clipse released the excellent, machine-worked Let God Sort Em Out this summer. The brothers were together again. After a career’s worth of impingements, it was all happening.

The best surprise? This is Malice’s album. Pusha will always earn his flowers, but on songs like “Chains & Whips” and “M.T.B.T.T.F.” Malice locates himself in the boom-bap, 4/4-time tradition that DMC and Biggie belong to: “Embalmed and bloated, now they viewin’ you/They never find the guns but the sewers do.”

Both Pusha and Malice have elegies for their parents on Let God Sort Em Out. Malice’s rings with heart-breaking granular detail: “Found you in the kitchen, scriptures in the den/Half-written texts that you never got to send/Combin’ through your dresser drawer, where do I begin?/Postin’ noted Bible quotes, were you preparin’ then?”

What brought Clipse to Vatican City for a career crowning performance this year is the truth that only middle age can bring: Work comes and goes. Family is eternal. – Evan McGarvey

As best I can tell, there is no word in the English language that encapsulates the experience of loving a city that will one day be underwater. Nostalgia, grief, and mourning, for their backward preoccupation, are not quite right. Loving a precarious and endangered city is as intoxicating as it is heartbreaking. Perhaps the closest articulation I’ve heard comes on “Crush,” the half-way point of Nick León’s hopelessly romantic A Tropical Entropy. On the jangly sketch, León sings “cuando estoy contigo, no me importa nada…yo soy un adicto.” That he could be singing to a fleeting lover or Miami itself is the whole point.

A Tropical Entropy, León’s full-length debut, finds the Broward Boy smuggling the full run of his interests as a DJ into an electronic record’s clothing. Across its tight half hour, the record flits from colossal Adaptation-inspired barnburners (the standout “Ghost Orchid”) to glitchy freakouts (“Hexxxus”). On the road to album-closer (and song-of-the-decade contender) “Bikini,” León dallies with bedroom pop, Clams Casino-indebted cloudy instrumentals, club-ready workouts and festival-sized anthems. The net result is an intoxicating diagram of León’s imagination and the city that’s shaped it. The ride is muggy, dizzying, and tender alike; sun gives and takes, and the light doesn’t always feel good in your eyes. It’s hard to shake the feeling that the record’s overriding aquatic ambience isn’t a mission statement in its own right: towers get built, filled, and abandoned, crypto assholes boom and bust, out-of-town clubbers come and go, and water rises, but the people who make the Miami what it is find a way to swim. – Ock Sportello

When a rapper known for paranoid sweating through auditory hallucinations starts talking about how they’re proud of sleeping well, core audiences tend to feel conflicted. Nobody wants their favorite artists to suffer, but recovered addicts who centralized drug abuse in their early work have a more difficult time convincing fans that their restored well-being has a positive impact on their music. We’re happy for No Malice, but admittedly happier when he re-drops the prefix. For Danny Brown, what now follows the blunt after blunt after blunt after blunt after blunts is, to put it bluntly, a better version of his same self. Stardust, Brown’s first full-length since getting sober, is his Recovery: an ode to and declaration of lifesaving clarity. Because he’s Danny Brown, the album evades the trappings of archetypal post-rehab projects. He delivers the wisdom of clarity with a crackle, amid fragmented, dissociative glitches of synth-heavy production that sounds like a DMT entity breaking and entering into the simulation.

Brown began referencing his newfound sobriety circa 2023, during the promotional cycle for Quaranta, an album recorded under the influence. His affect was flatter on that album, his delivery characterized by a subdued darkness. Stardust is a palpable revitalization. Even as his lyrics drift toward Tony Robbins territory, the production choices accentuate the message Brown delivers: he’s found himself.

Every Danny Brown album is an honest self-excision: a “chapter” of his life, as he says on “Book of Daniel.” Stardust isn’t the first time he’s referenced Daniel in the lion’s den, but perhaps it’s the first time he’s believed the Biblical tale’s ending. With a life reset on a triumphant course of spiritual prosperity, Stardust finds Brown leaning into the weirdest shit that inspires him more so than he has on any album since Old. In 2013, working with Purity Ring or making a song called “Dubstep” with Scruffizer was the equivalent of enlisting features from underscores, JOHNNASCUS, femtanyl and Jane Remover. Brown never hid the Dizzee Rascal influence, and shreds of what some now call hyperpop or fragment into infinitesimal meaningless subcategories pervade his entire discography. On “1999,” Brown says “I’m old school like Kangol, but stay on that new shit.” With Stardust he both shed light on a more niche underground sound and demonstrated that he belonged there, too. As divergent as the production is from previous albums, it’s not surprising. Like Earl (who Brown name checks as part of the big 3 alongside him and Kendrick) on Live.Laugh.Love, Danny’s mental health resolution has allowed deeper, truer stylistic choices to flourish. – Will Hagle

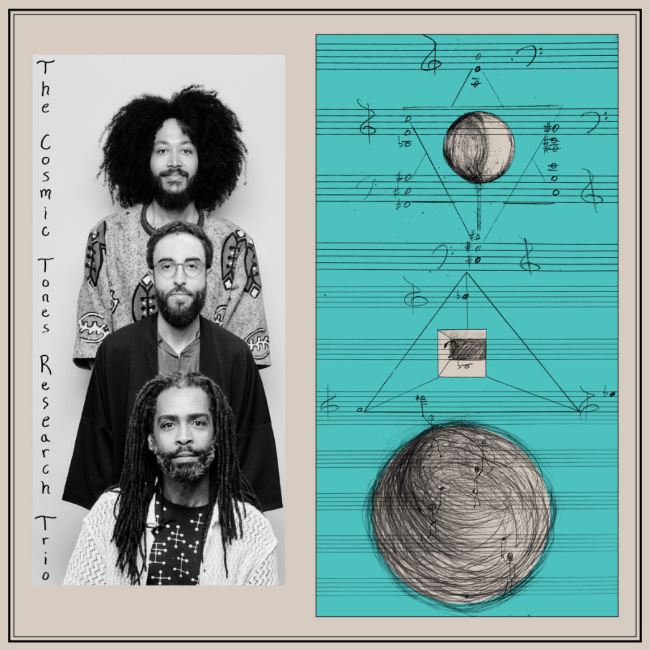

The self-titled sophomore album by Portland’s Cosmic Tones Research Trio carries its user manual in the linernotes: “This is not background music.” Of course, it can be used that way. Since their 2024 debut, All is Sound, the trio has proven enough ambient sensibilities to become, in a Brian Eno way, the most elegant presence in any room. But without full focus, you’d lose out on the nurturing qualities of this rich, complex musical conversation between alto sax (Roman Norfleet), cello (Harlan Silverman), and piano (Kennedy Verrett). “Spirit of Truth” pulls you in with hypnotic circular motives, while album stand-out “Ba Hi Yah” marries the onomatopoeia of Joe Henderson with gentle-but-deadly chord changes reminiscent of Ahmad Jahmal at his most spiritual. The patient drones of “Invocation” and “The Secret Garden” ground you, while the steady groove of “Sankofa” gets you going. Anyone who has had a chance to experience this music live knows how crucial this type of movement and communality is to the Trio’s performance.

Throughout these eight new compositions, the three-piece pulls off another magic trick. Despite all its precision and discreet minimalism, their music is never too slick. At no point does it feel like Seancè Day at Blue Note, but like a gentle invitation to travel inward, on a solo trip that gets more profound, more disorienting, more rewarding with each passing minute. It’s a calmness that goes beyond comfort. A subtlety that pierces right through your consciousness. – Julian Brimmers

For someone who’s lamented that she’s “tired of the internet,” Oklou (pronounced “Okay, Lou”) sure manages to balance the digital with the delicate on choke enough. Her fatigue drives her to seek corporeal connection in an online, atomized world. Despite her Soundcloud roots and affiliation with hyperpop, it’s that yearning that has been the classically trained French musician’s raison d’etre across the past decade. Whether it’s the intimate loneliness that formed the core of 2018 EP The Rites of May, or the comedown-after-a-night-out introspection of 2020 breakthrough Closer, it’s an oeuvre that often oscillates between nostalgic whimsy and a tentative longing for something real.

Here Oklou’s yearning folds back on itself. Dreamy synths intertwine with baroque-like polyphony throughout the album’s 13 lush tracks, with her gossamer voice floating over gentle melodies that trigger sepia-toned recollections. Standouts like “ict,” with its wistful la-la-las and twinkling trumpets, serve as a giddy love letter to her ice cream truck driver. “harvest sky” has her recount her halcyon summers as a young Marylou Mayniel dancing with other children at bonfire festival La Fête de la Saint-Jean. It’s almost as if Oklou is treating memory as a hybrid space—one that’s shaped by digital repetition as lived experience in which she doesn’t sever the cord between screen and skin. choke enough finds its power in restraint rather than volume, proving that in an age of constant amplification, human intimacy can still resonate the loudest. – Oumar Saleh

The birth of a child is a line drawn backwards and forward through time—or rather, it’s the revelation that that line was there all along.

Future: the continuation of your blood into the next generation. It is a joy that, as I say to my daughter regularly, I didn’t know I was capable of feeling. It’s also the appearance of a giant invisible clock in the sky counting down to your death. “You will not outlive her,” a voice said after my daughter was born.

Past: Memories of your own childhood flood back. Good parents carefully examine them, choosing what of their parents’ behavior to emulate and what to discard. The bad simply perpetuate the dysfunction—wittingly or unwittingly.

For Dijon Duenas’s second album, there never could have been any title—or concept—other than Baby. It is the sound of that line, in all its jaggedness, blurriness, beauty. The future begins on the title track, leaps forward ecstatically on the second, then shoots into the stratosphere, appropriately, with “Higher!” The first quarter has the feel of a great sermon, which pastors like to say entails telling the congregation what you’re going to say, saying it, and then telling them that you said it. The gooey center of the album—shouting out his wife who actually, y’know, made the baby—peaks with “Yamaha,” the next in the line of great songs about women as cars. Or maybe synthesizers.

And then Dijon begins to “Rewind,” raking himself over the coals for passing on to his kid what he dearly doesn’t want to. “Turn a lock and pick out a weak spot—you think he can’t learn that?” The target shifts on “My Man,” to the father who left him emotionally but who he can’t quite seem to leave physically. The song crumbles near the end, devolving into impressionistic blurts, “After calling his line…How can I leave? I can’t leave!” he sings. The last verse is an expressionistic howl about fire and smoke. The lyrics themselves matter less than the violence the sounds convey. Violence that Dijon has felt inside him all his life. Violence that he perpetrates on himself—literally or otherwise—because of the fears brought to the forefront by that Baby.

But the album ends with love, both carnal and romantic. Dijon’s wife gave him “that complete kind of love/knees buckling/the ‘I cannot speak’ kind of love.” It’s a reminder that though the line is present in our lives, it need not characterize them. Life is neither countdown nor rehash. It’s being here, with the people we love. “What a beautiful thing.” – Jordan Pedersen

Just ten days into his term, the right-wing Bolivian president Rodrigo Paz turned the nation’s clocks clockwise again. More than a decade prior, Evo Morales’s government had flipped the conventional Western clock atop La Paz’s Congress; in the seat of Bolivian power, one was now to the left of twelve. The adoption of this “clock of the south,” as it was dubbed, was described by the then-president of Congress as “a clear expression of the de-colonization of the people.” Here was a celebration of indigenous identity, a de-prioritization of the colonial north. As Foreign Minister David Choquehuanca asked: “Who says the clock always has to turn one way? Why do we always have to obey? Why can’t we be creative?”

You know what they say about books and covers. But what about records? When you press play on Los Thuthanaka, the joint record from world-beating siblings Chuquimamani-Condori and Joshua Chuquimia Crampton, you are bombarded with a series of zaps, samples, explosions, strings, and tags; you are also met by the “felinized clock of the south” that serves as the record’s artwork. A blurb won’t help you untangle this dense, magnificent collection of trance-like sonic collages. The deep-fried cat-like clock of the south might.

If music is keeping time, then Los Thuthanaka is an exercise in decolonizing it. Here is a record of long, knotty, rich songs that position their listener not unlike the Angel of History gazing backward in its wake. Los Thuthanaka reveals itself in reverse: each new movement simultaneously off-putting and in retrospect inevitable, each crescendo the result of an inexorable march and the synthesis of something completely new. Revanchist politics, nostalgic fetishism, and scam machine learning have conspired to create a culture obsessed with turning back time. Los Thuthanaka asserts a revolutionary, competing vision: why can’t time turn forward and counter-clockwise at once? Or: who says clocks can’t purr? – Ock Sportello

The official 2025 Word-of-the-Year Gold and Silver medals went to “slop” and “rage bait,” and as usual, the lexical pedants were misguided. No one can ignore the internet’s devolution into a pink sludge Styx where Cro-Magnon streamers seduce CTE-wracked wide receivers into hitting the blood libel Dougie. But having toiled through the clickbait wars of the 2010s, I’m old enough to know that both Ecclesiastes and Nas were both right when they declared that there’s nothing new under the sun. We have wallowed in rage bait and slop for over a decade, and if you don’t believe me, I have a Buzzfeed “35 People Who Just Realized That Seth McFarlane Is Actually Hot” list for you to sell display ads against.

My letter to the editors of Merriam-Webster and the OED is straightforward: 2025 was the year of the “Unc.” Even though Malice is literally a grandfather, Clipse dropped one of the most technically impressive rap albums of the year. And their impeccable press rollout relied on the good clean hating of the youth that has sustained elders for millennia. Freddie Gibbs and Alchemist are creeping close to the century mark combined, and at their flawless sold-out concert at the Novo, the median age of the crowd was 25 – proving that Alfredo’s ability to remember seeing the original Jurassic Park in theaters was no hindrance towards mass adulation.

When I caught Earl’s “I Don’t Like Shit I Don’t Go Outside” 10-year anniversary show, the last 20 minutes were devoted to him and his friends skating around the stage to anthems from 2015. The artist behind this annum’s best rap album declared it “Uncs on Ice.” And if you examine Rap Caviar’s top yearly streaming rappers list, you’ll see that the majority of them are either well into their 30s and 40s, or an undead vampire estimated to be 452 years old.

Out of all the viable candidates, the most vital emissary of Unc philosophy was one of the youngest, 30-year old, MexikoDro. Maybe you can trace the existential weariness to the fact that the Plugg music pioneer started rising out of the Soundcloud abyss over a decade ago. But there’s something to the Atlanta rapper/producer’s moral compass that reminds me of the oldest school of rap – the time when Melle Mell warned about the white line highway and DMC stressed the value of trade school.

On “No Date,” Dro declares “I ain’t doin’ all that punk ass shit to go viral.” On “Marta,” he puts God first, even before slipping on his Dickie overalls. The last part of the stanza might as well be a serenity prayer:

Wake up, pray, finna start the day

Brush my teeth, wash my ass, then I wash my face

Throw my clothes on, cleaning up my space

Before I walk out the house, I’m lifting up some weight

Fell back on drinking, n—-, now I’m getting sharper

Third day in, I’ve done started moving smarter

Got off track, had to go harder

Cause I ain’t tryna’ fuck around and be back on no Marta

On paper, none of this works. It’s not all that tonally dissimilar from William Bennett or even Jordan Pederson. But Dro possesses timeless intangibles: an unassailable sense of conviction, dignity, and self-respect. All qualities currently in short supply. In his videos, he’s stone-faced and severe, a volcanic statue carved on Easter Island and transported to the S.W.A.T. Most important is the prodigious musical talent that he views as a gift from providence. A disdainful monotone that booms like a bazooka warning shot. Beats that alternately fall like bludgeoning anvils and glide like a droptop old school. A ghost future cooked up in the trap houses of peak CTE and distributed two decades later on DSPs.

If this bounce passes-and-bank shots fundamentalism once seemed corny, it now seems almost radical in a climate of total amoral freefall. Zen and the art of Monte Carlo maintenance. Still Goin’ is sound of a man who has discovered his own personal code and the secrets required for survival. – Jeff Weiss

When the machines are getting smarter faster than ever, how could you not wonder when you will finally become obsolete? Nothing captures how positively schizophrenic it can feel to exist right now like DARKSIDE channeling the substance-addled Jack Nicholson character in all of us, as if creating art tomorrow isn’t a promise.

Shortly after releasing Psychic in 2013—a singular, polymorphous experimental electronica masterpiece—DARKSIDE went effectively dormant. Now, Nothing is the second album in the last four years from the duo of Nicolas Jaar, a French-Chilean New Yorker producer/multi-instrumentalist with a penchant for warping IDM, and guitarist/multi-instrumentalist Dave Harrington, a fixture in L.A.’s avant-jazz scene. Both are constantly redefining what it means to be an experimental artist, and Nothing is another exhibit of what an unmatched gift their combined powers can be.

This is the finest vocal body of work for Jaar. Over an exalted electrocumbia backbone on “American References,” Jaar sings, “Si no funciona, no me digas que funciona” (“if it doesn’t work, don’t tell me it works”). It’s one of the album’s cardinal grievances, and sees him grappling with the existence of nihilism for anything besides capitalistic monoculture. Is the only way to survive in a hellscape with some semblance of sanity to just not think about its truth? This idea eats away at Jaar and Harrington, who warble around decadent jams that are equal parts deranged jazz house and post-apocalyptic roots music while ambiently melting into an unknown fate after popping a soma. And let it be known, that on the day that buildings start to fall as militias rise up to topple autocrats, “Hell Suite, Pt. II” will be ringing through the skies. – Adrian Spinelli

It is a rare feat. There are many “celebrities” on TikTok trying (or letting talent agencies try on their behalf) to mutate into legit artists. None are like Addison Rae, the 25-year-old former cheerleader whose self-titled debut proved she’s a one of one among the class of aspirant vertical-video pop girls. But Addison is a mirror into the Lafayette native’s life through deeply personal songs that play like adrenalized, Gen Z Sex In The City episodes. Just under 35 minutes, it boasts high replay value, showcasing Rae’s distinct pop evolution. Tracks like “Diet Pepsi” have made your most listened to tracks this year because the song is a bop, and your ass does look good in those ripped blue jeans.

Collaborators Luka Kloser and Elvira Anderfjärd worked with Rae on Addison to make songs that sound like her personality, sprinkled with Southern charm and innocence. “Aquamarine” and “Headphones On” have undeniable Y2K nostalgia. “Summer Forever” has a floating, immersive feeling that plays year round. Taken as a whole, Addison is just the beginning of our collective obsession over her. Her fame is a gun, and she’s right on target. – Eric Diep

I get a strange feeling in my gut whenever I drop the needle on Sortilège. Yes, it’s one of the best rap albums of the year, a veritable masterclass in writing and production alike. And yes, it marks the beginning of a new chapter in Gabe ‘Nandez’s career, pushing him from niche indie concern towards a well-earned spot amongst the underground’s biggest stars. And yes, it further solidifies Preservation’s status as one of the greatest loop-digging auteurs the artform has ever seen. But it’s more than just dope beats and dope rhymes. There’s something under the surface that a blurb or an interview can’t quite capture.

These two artists bonded over their shared Francophone heritage and a love of ‘90s boom-bap, but they were brought together for a bigger reason. They’ve each touched the beyond somehow, probably in ways they’re unaware, and those types of people tend to find each other. Pres connects threads across geography and generation, building an aural history of humanity one dusty dollar-bin sample at a time. ‘Nandez, who’s lived all over the globe, has walked up to and stepped back from the brink of addiction and annihilation, gaining a nearly supernatural understanding of human behavior. They wield turntables and pens as weapons against the erasure of history, against the daily onslaught of destruction that nips at our heels. Their music is psychedelic as fuck, not because of a battery of outboard effects or post-production tweaks, but because it’s a clear, unambiguous reflection of existence itself. Time gets stretched and flattened (“She 20, but she from the hood, so she 26”) and borders are shown to be the irrelevant, stultifying structures of division and oppression.

Sortilège is a grimoire for the dying internet age, a tarot reading in the traphouse, a spiritual text etched in a crystal skull. It’s a survival guide for when the veil gets thinner and the surveillance state larger; each syllable like the tracings of a Ouija board planchette, each line uttered by a soothsayer after a doomscroll. – Dash Lewis

The lush arrangements and breathy vocals that pulse over 17 luxurious beats on Rochelle Jordan’s Through the Wall make the album feel like skipping the line and hopping the velvet rope at The Electric Room. The British-Canadian’s third studio album draws inspiration from Janet Jackson and Crystal Waters, with a contemporary dash of Kelela.

Rochelle gathered an impressive group of producers, laying sleek polish on noteworthy tracks “Bite the Bait,” and ”Ladida.” Her sultry lyrics erupt with pointed confidence: “I know it hurts to see me looking so juicy, I know you want a taste,” she purrs at the end of “Sum.” Jordan displays range, even rap skills over the bouncy beat, “Ladida.” “Don’t be afraid to take up space,” Jordan affirms over the end of “Bite the Bait.” Through the Wall does just that. –Deb Ashley

Marcus Brown is one of us. The artist known as Nourished by Time named his album after a Purple Rain deep cut and he drops seven-minute Eric B. & Rakim remixes in his performances as a “dog whistle” to fellow “cultured individuals” (read: music nerds). After years of releasing music on his own under various aliases, Brown signed to tastemaker UK label XL on the strength of 2023’s Erotic Probiotic 2, recorded in his parents’ Baltimore basement. Because he was largely uninvolved with any real-world scenes, Brown developed his idiosyncratic sound in isolation, like a lifeform mutating in a petri dish.

On The Passionate Ones, Brown pairs reverb-soaked synths with grooves from boogie, house, trip-hop, and futurist pop girl groups; his unshowy voice fuses the album together, centered in the mix, largely without pitch correction, his Baltimore ties audible in the exotic shapes of his vowel sounds. “Baby Baby” is a too-many-tabs rocker where Brown chases sex and drugs and ponders that the powers that be can bomb Baltimore just as easily as they bomb Palestine. “If we all strike now, the gravy train stops,” he muses. When the jackboots kick down his door, they’ll find him with a lover and an excellent record collection. Who can relate? – Jack Riedy

In a single calendar year, Cameron Winter, the precocious Brooklyn zoomer with a formal rock education and a pair of parents with a very publicly open marriage, released not one but two albums that most people would have considered to be the album of his life if, again, he hadn’t pumped out two of them. The first, late 2024’s Heavy Metal, answered the question of what kind of album Bob Dylan or Leonard Cohen might have made if they’d grown up in a generation for whom the two most significant ambient cultural forces were COVID-19 and streaming pornography. The second, Geese’s Getting Killed, answered the question of what that same person would do if they were a collaborator in a band of musical virtuosos being guided by Kenneth Bloom (neé Beats), the trap-EDM dude turned premium hip-hop beatmaker who wanted to take a stab at getting his Brian Eno on. Which is to say, Getting Killed is big and weird and loud and all over the place—daringly, appealingly, in ways that prompt the more reckless and/or optimistic industry people among us to throw around phrases like “money printer go brrr,” “American Radiohead,” and “indie rock is BACK.” Let’s not get too far ahead of ourselves, if nothing else because placing the burden of expectations on such a young band is wholly unfair to them.

But let’s be honest: When someone in the public eye makes the leap, just as in sports, the speed at which they reach ubiquity draws suspicion. Are we sure Jalen Johnson isn’t just a taller Trae Young who can’t dribble? That Paul Thomas Anderson and Benny Safdie filming that Cameron Winter show wasn’t definitive proof that the fix is in? The answers to such questions are less important than the fact that just as it’s fun to have a new person or band to talk about, it’s just as fun to argue about whether or not they’re somehow fraudulent. Even the Geese haters are, in their hearts of hearts, fucking amped about Geese.

I get it, I really do. I am, in general, reflexively against popular things. But maybe it’s just because I’m soft and old, but I genuinely love this band and believe that their album earns every ounce of ballyhoo directed its way. I love Getting Killed’s liberal use of bongos, its implied non-rejection of the phrase “exploring the studio space,” and that live, Geese stretch these songs out to Bonnaroo-esque lengths with the verve of kids who just found out about My Morning Jacket. I love that “Long Island City Here I Come” sounds like the entire E-Street Band being thrown down an endless flight of stairs and romanticizes a neighborhood that’s basically just condos at this point. I love that “100 Horses” pretty brazenly jacks the bass groove from Radiohead’s “The National Anthem,” if not note for note at least vibe for vibe, and that they performed it in that one Radiohead guy’s basement for maximum Iverson-crossing-over-Jordan effect. I love that Cameron Winter talks like Elvis and lies through his teeth to reporters like he thinks he might get the lead in the sequel to A Complete Unknown. And I’m not worried about whether these kids can catch lightning in a bottle twice. Derrick Rose won MVP his third year in the league. He’ll always be a legend for that. – Drew Millard

On F.L.I.N.T., Rio flits between casual flexes, paranoid asides, and grim reminiscence, making his verses feel like unfiltered monologues from a prison bunkmate rather than polished rap tracks. This all makes sense considering 2025 is the year the Michigan hero properly returned to the studio after a nearly five-year-long stint in the feds. His return home felt like a victory in itself, but the music Rio immediately dropped felt like the strongest post-prison return since Tee Grizzley’s ever-influential “First Day Out,” released in 2017. It showed that a combination of pre-recorded music and genuine talent has given Rio a second chance at rap stardom, something some artists aren’t so lucky to have.

F.L.I.N.T. is an evolution of everything we’ve come to love about Rio: his eye for detail, his comedic-timing, the cutting one‑liners and the specificity in his storytelling. It creates a kind of intimacy that’s hard to reproduce, in the same spirit as fellow Michiganders Eminem and Danny Brown. Rio, who has been very open about his aversion to writing down lyrics, is the type of distinct orator who shows more than he tells. It makes for more dense works, like “Another Story” and “Back Rubbed,” that don’t treat the listener like a moron who needs their hand held as he explains that when he found out his cousin died from taking a pill laced with fentanyl, Rio popped one himself just to get through the pain. Over 20 songs, Rio takes a longform approach to officially announce his return to rap, and what he ends up with feels as dense and rich as a James Joyce novel, with the hometown love and familiarity of Sherwood Anderson’s masterpiece Winesburg, Ohio: A Group of Tales of Ohio Small-Town Life, which used a quiet Midwestern town to help helped reinvent what American fiction could do, both in style and in subject. –Donald Morrison

From the outset, Lifetime feels like a distant memory. Like it’s a soothing lullaby delivered from behind a closed door, where the only escaping substances are warm amber light and muted samples, filling the hallway with a siren song designed to lower your guard with a seductive softness from a bygone era. The comforting blanket of baked in nostalgia (stopping short of pastiche with mutations that marry modern R&B musings with the old) is familiar for those accustomed with Erika de Casier’s previous record Still, where the Portuguese-born, Danish-raised singer traps you in the metallic sheen of 2000s Missy Elliott and Aaliyah like a time capsule the color of a silver bullet. When de Casier dropped Lifetime this year, self-produced and released into the world without an ounce of fanfare, it arrived like an unearthed secret. A silky, cooler older sibling finally showing you their treasure trove of Janet Jackson and Sade tapes, freestyling along with their own brand of heartbroken, yearning murmurs—charting a new course for you to follow without even knowing it.

There’s times on Lifetime when it seems as though de Casier is glitching while moving between her influences of the past and her present meditations. The tracks fade in-and-out like hazy recollections, pulsating with understated beeps and whirrs from trip-hop elements that feel beamed from the future; her voice is littered with reverb and distortion, resting on a cloud of synths and drums that could only emanate from a SEGA Dreamscape. Through it all, de Casier’s wandering attention lets you settle on her romantic aches (“I’d rather be close to you,” from the hook of “December” lilts in your mind), and simplest insecurities (“When the light’s out/Do you still see me,” she asks wistfully on the title track). Her tranquil nature belies an intense clarity, a crystalline underlying vision delivered through a shaky dial-up connection, landing with a blow so soft that it registers as a loving caress. – Matthew Ritchie

Eventually, every pendulum swings back. Dancefloors can only be hard, fast, and messy for so long. Eventually even the toughest raver needs a comedown. Friend, the third LP released by New York’s resident cloud sculptor james K, is both suspended in time and outside of it. Some of these tracks have been inescapable for what’s felt like years: “Blinkmoth (July Mix)” is, at this point, a reliable featherbed for particularly exploratory DJs, and several other cuts here feel like they’re of a piece with trip-hop revivalism that’s captured the dance-music world writ large. At the same time, Friend is working on its own frequency; it is indebted to all manner of genre histories but beholden to none of them. Crack it open and you’ll find all manner of forms bubbling up from the murk. The sound of Friend is the sound of barely-there breakbeats rattling against a rack of guitar pedals; it’s Elizabeth Fraser-esque vocals that prefer silhouettes to photorealism; it’s pillow-soft synth tones and bleary-eyed drum breaks and mountains of reverb.

Perhaps the most impressive thing about Friend is the simplest: james K makes good on the record’s title, cooking up a record purpose-built for 3 a.m. intimacies left half-spoken. Thanks to its sepia-toned palette, it’s an easy hang, but spend enough time with it and you’re bound to find traits to love: Perhaps it’s the way james’s syllables dissolve into the synthesizers, or the way a hi-hat peeks out from the fog before disappearing, or the sub-bass tones primed for soundsystems and headphones alike. Or maybe it’s all of the above. – Michael McKinney

Calling your album a movie is played out. GOLLIWOG, though, demands the comparison. billy woods’s latest, most visceral album opens with the soft purr of a projector; through gruff barks and paranoid whispers, woods puts on one dread-inducing performance after another, narrating vampire love triangles, unshakable clouds of paranoia, and banned basements finally unlocking. But what haunts him more than devilish puppets and revenge-seeking drug dealers are the life-altering epiphanies all those pounds of kush can no longer seem to blur out. The realization that the bond of mother and child is as powerful as it is fleeting, the desire to sleep in peace with no strings attached is a fairytale, and the possibility that all our fates were fast-tracked to damnation by sins committed long before we had a say.

Speaking of having a say: On “Jumpscare,” GOLLIWOG’s introductory track, woods raps: “The English language is violence/I hot-wired it/I got a hold of the masters tools and got dialed in.” As in the rest of his catalog, woods here uses the language and logic of colonizers to describe the horrors they leave in their wake. Think “Corinthians” and the “12 billion USD floating over the Gaza Strip,” the dread that builds in a politically split family amidst a revolution showcased in the first verse of “Waterproof Mascara.” Then there are the manmade ills attached to small-time colonial mindsets: a landlord throwing a family out before the holidays on “BLK XMAS,” the tension of surviving street life and its many laws from “A Doll Fulla Pins.” As the shockwaves of these events widen out like ripples in a pond, the stories become more warped and surreal, reflecting how dystopian life becomes in the aftermath of such evil; remember the shucking and jiving for records execs on “Cold Sweat,” the supernatural psychosexuality on “Misery.” Will we act in changing our minds, spirits, and societal states, or will these fears and nightmares prove permanent? Fade out, slowly. – Anthony Seaman

Open Mike Eagle has long been a lyricist in a class of his own, heir to the self-reflective and -deprecating writings of The Native Tongues, Project Blowdians, and Soulquarians (midwestern branch™️). Bars, however, be they wordy or heartfelt, aren’t enough to keep a rap career afloat in a fast-fashion cultural environment demanding multiple drops per year for fans within carefully delineated market segments; so what’s Mike to do? Simple: graft those bars to the hookiest, most soulful music of his career, all without sanding down the idiosyncrasies that earned the art rapper plaudits in the first place.

Neighborhood Gods Unlimited is a full-spectrum look inside Mike’s psyche, whether he’s watching his phone get run over, imagining himself as an indie rap Kryptonian, or reminiscing on old part time jobs and 00s’ Looney Toons adorned streetwear. As in all things OME, the everyday nature of the topics barely conceals the existential dread inherent in modern life: a song might superficially be about a phone, but it’s really about the horror of losing part of ourselves to a digital shadow realm, having placed parts of our souls and creative output in a now smashed Apple-branded horcrux. And that’s not even getting into the record’s Prince Paul-worthy framing device: a public access TV show beamed from an alternate reality where “Cyclops Was Right” is a bigger meme than 6-7.

What truly elevates Neighborhood Gods Unlimited as Mike’s best work however, is how musically locked in every piece feels, be it the guest verses from long-time allies AQ, Still Rift and Video Dave or the earworms he deploys over a murderer’s row of beats by indieground A-listers shaping the boom of baps to come. Mike’s come a long way from mashing They Might Be Giants with De La Soul, proclaiming the virtues of art rap from the rooftops to all that would listen. Today, he’s done connecting dots, instead creating a whole new pointillist masterpiece of his own. – Son Raw

If there was ever such a thing as a pop playbook, Amaarae’s BLACK STAR folds it into origami and then lights it on fire. The 31-year-old Ghanaian-American globetrotter’s voice feels like an intuition from the back of your head. Raised between Accra, Atlanta, and New Jersey, she’s always existed slightly sideways to genre. BLACK STAR is her most ambitious project yet, detonating the safe coordinates of Afropop, electronica, and alté, and drenching the wreckage in a venomous black liquid. It’s dark, glossy, and genuinely cool without being unapproachable.

There is a dizzying joy to the dismantling of these traditional structures. She generates a world around her persona, identity, and culture where baile funk slams into Jersey club, trancey drill synths pad a patent-leather runway, and baby Carti voice tip toes over rolling cyberpunk amapiano grooves. All of it has this slippery forward momentum, where even when it’s looping, it’s all acceleration. Nothing overstays, and every track and sonic signature knows when to leave the party.

The album doesn’t teeter between the poles of vulnerability and hedonism, but rather throws them in a blender and comes out on the other side where it’s ludicrous to suggest there was ever a difference. On the PinkPantheress-assisted standout “Kiss Me Thru The Phone pt. 2,” she soaks her favorite sheets in longing. On “Starkilla,” she flips to a pulsating hook, screeching “ketamine, coke, and molly” from a post-physics dancefloor. In one breath, she can’t do no wrong because she’s just a baby. In the next, she’s a boss bitch, dripping her girls out in designer and wiring them for tummy tucks.

Gender and sexual fluidity move as a speeding blur. The black star on the Ghanaian flag bleeds into the luxury fantasies of Black icons past who feature on the album, from Naomi Campbell to Charlie Wilson, then refracts through Amaarae herself, landing in the dreams of young Black girls everywhere. History, aspiration, and self-mythology collapse into the same image.

Taken as a whole, the album feels like the dance floor at the coolest cocktail party in a universe where Black girls reclaim a power that was never actually lost, only mislabeled. The sonic borders are amorphous, and Amaarae stands at the center, queen of it all, strutting in some Blade Runner-ass fit, already living in the future everyone else is still trying to name. —Harley Geffner

There are rappers who deliver music in unbelievable deluges: Lil B in the last decade, YoungBoy in this one. Others—I’m thinking of Blu, of Jay Electronica—offer records that are obviously and tantalizingly unfinished. By contrast, Earl Sweatshirt’s are discrete, deliberate, seemingly bound by the normal rhythms of commerce. Even when the presentation could be read as an attempt to undercut this premeditation, as with 2018’s Some Rap Songs, the collage is so sophisticated as to suggest months of planning, editing, revision.

And yet few rappers—few artists working today in any popular medium, really—can claim catalogs so indicative of an ever-evolving practice. (That’s the alternate reading of the Some Rap Songs title: these are chips off an iceberg bobbing gently in bad waters.) Feet of Clay starts in medias res, that abrupt “You like Amar’e Stoudemire with dreads.” When the muddiness of his 2018-19 releases gave way to the steely Detroit bounce of 2022’s extraordinary Sick!, the shift in production was matched by a tighter fusing of Earl’s once-competing impulses toward curtness and spirituality. Whether the sound drove the themes or vice versa is impossible for an audience to know, as it should be.

Like every one of Earl’s releases since his 2013 studio debut, Doris, his new album, August’s Live Laugh Love, runs less than 30 minutes, a brevity that suits his dense writing and underlines that feeling that we are merely getting glimpses of what happens daily behind closed doors. Packed into these 11 songs are remarkable broad spectrums of emotion and sound. The sunniness of “CRISCO” and the opener “gsw vs sac” chafes against the grim militance of “FORGE” and “Static,” the pits of doubt he details on “Heavy Metal aka ejecto seato!” smoothed over by the wistful but pointed advice he doles out on “WELL DONE!”: “I see you ain’t moved in a while/Ain’t gon’ lie, you probably should get your sails up.” He moves, and he moves, and he moves.