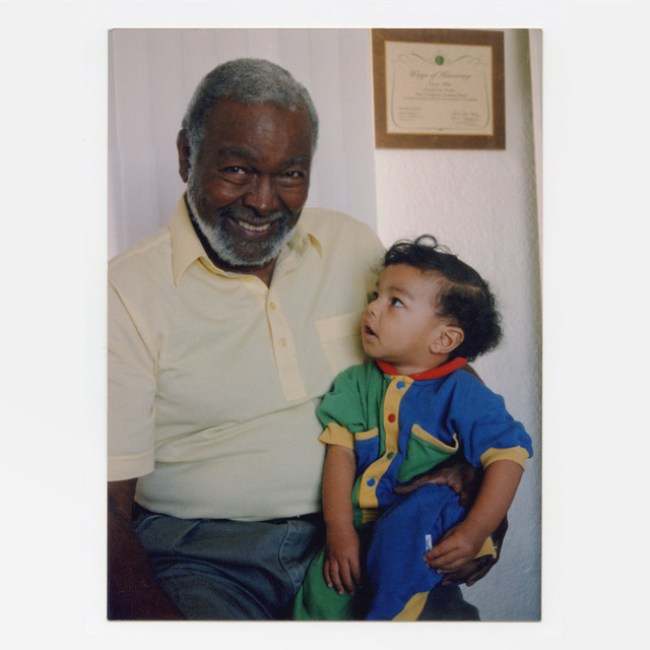

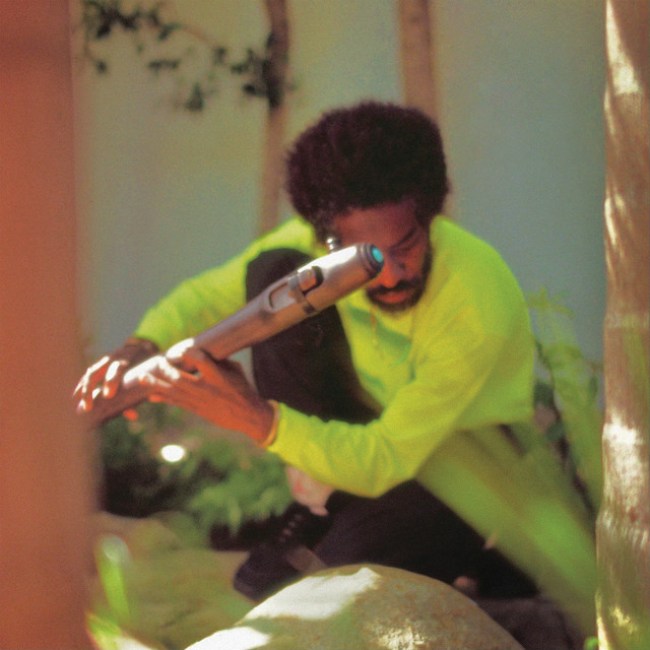

Chester Watson’s arrival into the upper echelon of hip hop is firmly cemented on fish don’t climb trees, his follow-up to 2020’s A Japanese Horror Film. First garnering attention at the tender age of 16 with his LPs Phantom and Tin Wooki, Chester Watson is reflecting on his artistic journey thus far with a bird’s eye view as he self-reflects on family, esoteric questions, and the pursuit of creative expression.

The 26-year-old St. Louis rapper and producer refers to himself as “trippy but level-headed” on “i feel alive”, summing up the ethos of his mindset on the project. Fully written and produced by Watson, fish don’t climb trees pulls the multi-hyphenate into deeper explorations of surrealism and existentialism approachably framed in vivid imagery highlighted in songs like “grey theory” and “mirrors”.

The album’s title stems from a quote often attributed to fellow polymath Albert Einstein, who may or may not have claimed that “everybody is a genius, but if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid.” The embracement of unconventionality comes easily to Watson, who first garnered an education in classical music theory through his pursuit of ballet at a young age. Going back to his early love of storytelling and movement, Watson’s productions are vibrant and primal in their musicality as the artist pulls from his earliest roots of creativity to integrate his past, present, and future selves in an impressively self-aware addition to his discography. – Staley Sharples

If there’s a friend or loved one with whom you have unresolved tension, the New Jersey band Yo La Tengo have a solution for you: This Stupid World. Each track moves through the phases of intimate conflict: “Sinatra Drive Breakdown,” “Fallout,” “Apology Letter,” “This Stupid World,” and “Miles Away.” By the end, you might still choose to separate, but at least you’ll laugh about how ridiculous the conflict was in the first place. Catharsis guaranteed.

Yo La Tengo have spent the better part of nearly 40 years making indie rock original constitutionalists actualize their feelings. They’ve mastered somber guitar rock – drawing inspiration from all-genre greats ranging from The Velvet Underground to Sun Ra. The trio create music for the emotionally aware, songs that can thrash and rehabilitate both mind and body. I Can Hear the Heart Beating As One remains a classic: supplying accessible guitar riffs that still shred, and nonsensical yet profound lyrics. With This Stupid World, Yo La Tengo deliver a continuation of the emotional bloodletting a quarter century after that early masterpiece.

The title track: “Sinatra Drive Breakdown,” is named after a street from the band’s native Hoboken. The song opens with a ring of electric guitar, followed by a grounding bassline from James McNew. Simultaneously, the rhythm mingles with guitarist/vocalist Ira Kaplan’s disembodied lyrics, “I sit here far from you / I see something regained and lost again.” It’s hostile nostalgia, felt by someone who’s left home or a relationship, only to return as a foreigner. On “Aselestine,” drummer/vocalist Georgia Hubley patiently admits a raw confessional over acoustic strumming: “I wait for you / It’s not the same.”

Yo La Tengo may not be entirely subtle in their existentialism: “This stupid world, it’s killing me. This stupid world / Is all we have,” Kaplan sings on the title track. As with life, the album ends with no finite solution to life’s conflict and pain: “You feel alone / Friends are all gone.” The only comfort they can offer is not to take this stupid world too seriously. – Liz Sanchez

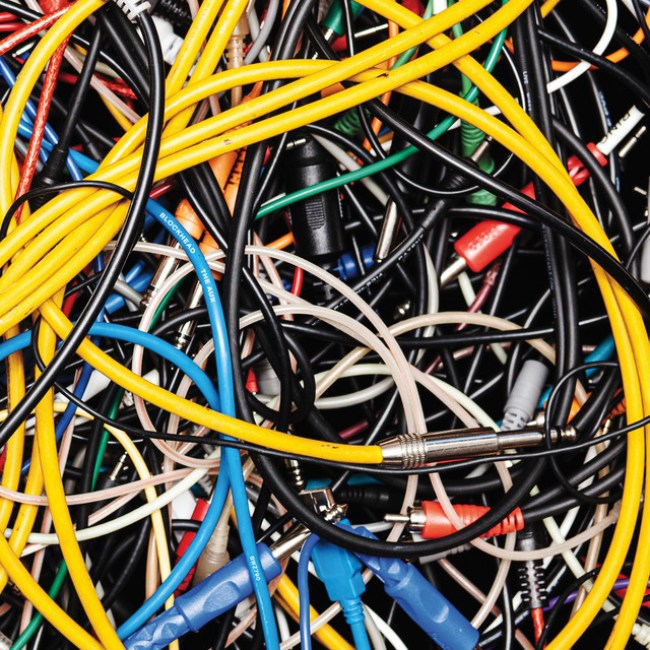

Dipset wasn’t wrong when they declared themselves a movement two decades ago. And as of 2023, if anyone on Backwoodz Studioz would proclaim the same, they wouldn’t be incorrect either. Over the past few years, a scene of rappers for whom intellectualism doesn’t equate to elitism has coalesced around the record label billy woods built. They’re joined by beat creators pushing the boundaries of east coast hip hop, rather than just retracing DJ Premier at his apex. This swirl of artists feels like an echo of Def Jux’ heydays; adventurous underground rap unafraid of abstract flourishes, or putting mood and texture over melody.

And just like with Def Jux, plenty of these artists often aren’t even signed to the label. But there is a shared sense of purpose and aesthetic, of which Backwoodz currently is the epicenter. A world of rappers and beat creators as unencumbered with what might place you on the Rap Caviar playlist, as lambasting the people on it. This is art rap, a moniker that by itself isn’t easily defined. For the uninitiated however, that doesn’t leave much of a way in. It feels fitting that The Aux, arguably the most welcoming record to come out of this rap renaissance up until now, is spearheaded by a producer who actually was one of those trailblazing Def Jukies himself — way back when Cam’ron was rocking a pink fur coat.

Blockhead’s The Aux offers a smorgasbord of smart rappers spanning generations; from Brian Ennals to Breeze Brewin. The unifying element is the puckish production, which runs the gamut from grimy (‘Lighthouse’) to playful (‘Mississipip’), but always with a sense of buoyancy. Whether it’s a funky drum lick or a quirky vocal sample, there’s always a lively, almost mischievous element in these beats. It allows each rapper to just have fun, and with a swath of wordsmiths this talented, that’s all you really need. If someone ever asks you where to start with all this Backwoodz stuff, just pass them The Aux. – Jaap Van Der Dolan

Forget what you’ve been told about Navy Blue for a second. Dude can rap. Really rap. Ways Of Knowing was the one where I really internalized that about him. Maybe cuz almost every critic and their mom likes to write about him like he’s some kid reading from his diary. Yes, it’s confessional music, yes he’s baring it all, but did you even hear how he skated on “Chosen?”

For his Def Jam debut, he’s graduated from his submerged mixes and barely-there soul loops to sliding on Budgie’s glossier ones “like amusement parks.” Forget samples, Budgie hooks Navy up with damn near the source material: buttery drums, dub rhythms, somber horns, wafting piano, percussion that’s a little quirky and just right—is that a clock ticking on “Window To The Soul?”

These beats push Navy out of the dense haze of past records and into a brightly-lit arena where everybody can really pay attention to the raps. He’s sharper than ever, rapping in tight circles, floating around the drums, even singing his heart out at times. And the hooks! The refrains! Stacked full of vocals and flown in by Navy and Budgie like muses, I hear in them the gospel influence he’s spoken about.

But it also sounds like Navy might’ve listened to Ka’s more melodic joints, which themselves feel like transmutations of Dungeon Family spirituals, and said, “I wanna write these from my perspective.” And that’s where I’m supposed to talk about how I’m also 26, and this record hit me at the exact right moment in my life, and every time I walk outside lonely and the sun’s setting I look up and mutter, When nothing else work, I’m settled on the sky gradients, and when I saw him do “Pillars” at Market Hotel with the lights off I bawled my eyes out as he buried his face in his arm, but I’ll shut up. What did he say–The weight of what I don’t say is heavy! – Mano Sundaresan

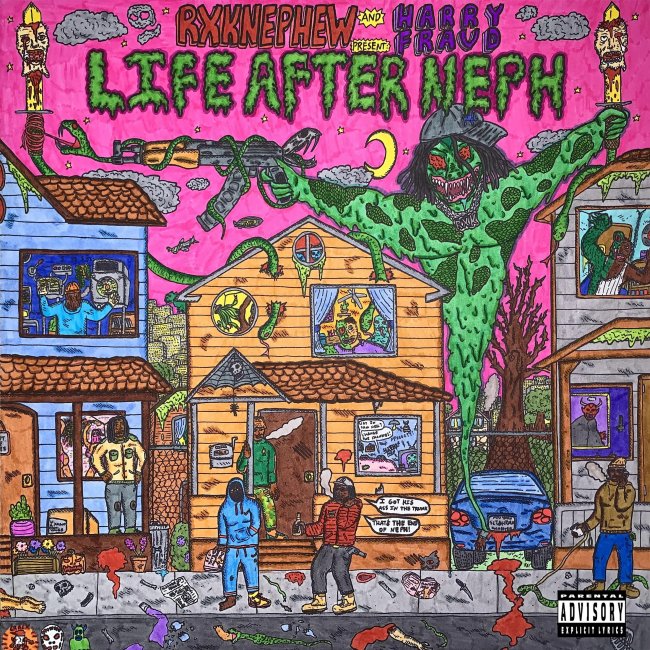

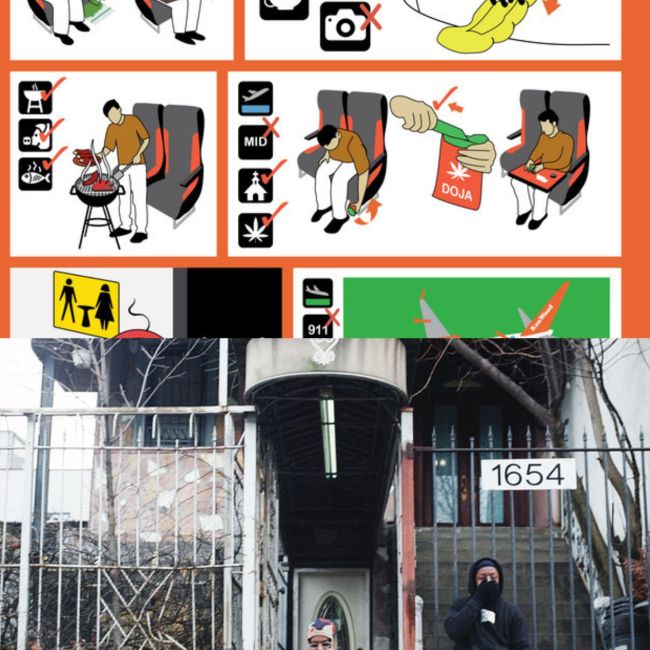

On paper, LIFE AFTER NEPH wasn’t supposed to be this wavy. To the uninitiated, it boils down to how different RXK Nephew and Harry Fraud might seem. As rap’s anointed agent of chaos, the prolific Neph (as I type, he’s likely dropped another lawless loosie on YouTube) thrives in anarchic delirium, unafraid to call out Kanye and his Yeezys for “being ass” while speculating whether Christopher Columbus would’ve gotten shot in his stomping grounds of Rochester, NY. On the other hand, the seasoned Fraud is a laid-back vet whose raison d’etre is slow-cooking whimsical sounds and dreamlike synths that trigger vivid visions of flybridge yachts, silk robes, and fully-stocked humidors.

However, given their shared love of the still-incarcerated Max B (“Free Uncle Max!”, Neph bellows on the outro to triumphant opener “Pebble Beach”), we shouldn’t be surprised that they managed to concoct a concise, yet cohesive record. It stands out as one of the year’s most kaleidoscopic releases. Despite reining in his rabid Slitherman alter-ego, there’s enough random pop culture callbacks and out-of-the-box oddities to sate long-time Neph devotees – who are perhaps unfamiliar with him gliding over beats as luxurious as Fraud’s.

The combative American Tterroristt summons the spirits of Avon Barksdale and Damon Wayans’ hard-as-nails Major Payne on the Valee-assisted “Authority Figure”. He’s left wondering how he’s gonna eat a “plate of coke with a fork” on the ghostly “All Gone.” Neph’s outlandish irreverence even gets Fraud to depart his hazy comfort zone with the bombastic album closer “Top Chef Neph.” Here, Neph demands a Tomahawk steak and shark-infested seafood boil while deriding everyone else’s dinner as “3D-printed”.

This year, Neph and Fraud showcased their versatility through numerous collaborative projects with other like-minded peers. But what sets LIFE AFTER NEPH apart from the rest is the odd couple’s unbridled chemistry amid unfamiliar surroundings. For two virtuosos at wildly contrasting stages of their careers, their zany 11-track odyssey signals a fun new direction for both. It would be a travesty if they didn’t follow this up with something even more lavishly unhinged. – Oumar Saleh

Pink Siifu claims no territory, geographic or sonic: he’s lived all over the country and in recent years has excelled at aggro punk, dusty bars-on-bars raps, and aquatic funk. Together with Long Beach producer Ahwlee as B. Cool-Aid, they make “family reunion music,” a combo of grit and groove to provide the pulse for multi-generational kick-backs. Their new album Leather Blvd. soundtracks an imagined, ideal Black-owned neighborhood. It’s inspired by the neo-soul sounds of Badu, Jill Scott, and D’angelo and the Yodas before them, like Sly, Prince, and the Ohio Players. As John Morrison wrote, this imaginary street “could be in Stankonia, or it could be on P-Funk’s Mothership, or in Henry Dumas’s Holly Springs – or any other place where Black folks can imagine a world in which we are able to create, make love, and be free.”

This is music made by people who love being together. Siifu and Ahwlee were friends first. Veterans of the Low End Theory beat scene, they met at a birthday party for fellow producer Mndsgn and discovered a similar sense of humor and style. They developed these songs through a post-modern jamming process: Ahwlee made beats from samples of a Richmond jazz group Butcher Brown and instrumentalist DJ Harrison – who then re-recorded the new compositions under Siifu’s vocals. After that, they swaddled the tracks in layers of communal backing vocals and guest appearances from like-minded soulsters like Liv.e, Quelle Chris, Ladybug Mecca of Digable Planets, and Dungeon Family figurehead Big Rube. The result is warm, lascivious, and endlessly listenable. It’s like the rambunctious little cousin to Voodoo. Do you like having fun and feeling good? Then be sure to drop by Leather Blvd. – Jack Riedy

Going out to the function is as expensive as it’s ever been. And, depending on your persuasion and quality of face covering, it’s never been riskier. Are we collectively getting crankier and shouting at clouds? Is this a brief flare of disaster capitalism and social anxiety, or is leaving the crib at night getting markedly less dignified? U.K. DJ duo Overmono offer both an urgent corrective and gentle lament for lost feelings in Good Lies. It’s their spacious and fuzzy piece of inverted club revival.

Despite the album’s simple visual motif of a dusty car and a panting dog, Good Lies is thrilling and unpredictable in its entirety. The cavernous percussion of “Arla Fearn” suddenly shifts into colorful chamber pop on the title track, while “Walk Thru Water” and its distorted melancholy gives way to the dancehall miniaturism of “Cold Blooded.” Overmono’s latest project sounds like a machine fighting itself in reverse, a ketamine high that somehow spikes once the party wraps and the chambers release its revelers.

Welsh brothers Tom and Ed Russell make a long-anticipated, full-length debut while throwing everything at the wall. Then, they summarily rattle the wall down with electroacoustics. It’s as if Overmono makes compositions in textured, detailed greyscale, then casually splice neon-lit vocals wherever and however they see fit. The bouncers are still sweaty and overzealous, and drink prices may never go back down, but we can absolutely demand this level of ambition from our dance music going forward. Not much is said within the confines of Good Lies, but absences are accentuated with searing intensity. – Steven Louis

It’s easy to fake spontaneity for the sake of advertising. Look at the focus-grouped releases across every genre: they’re covered in synthetic varnish and bloated with the assurance that a thinking, feeling human™ made this. Genuine novelty can’t be faked, though. And every time WiFiGawd releases a new tape, ingenuity emerges from the catacombs.

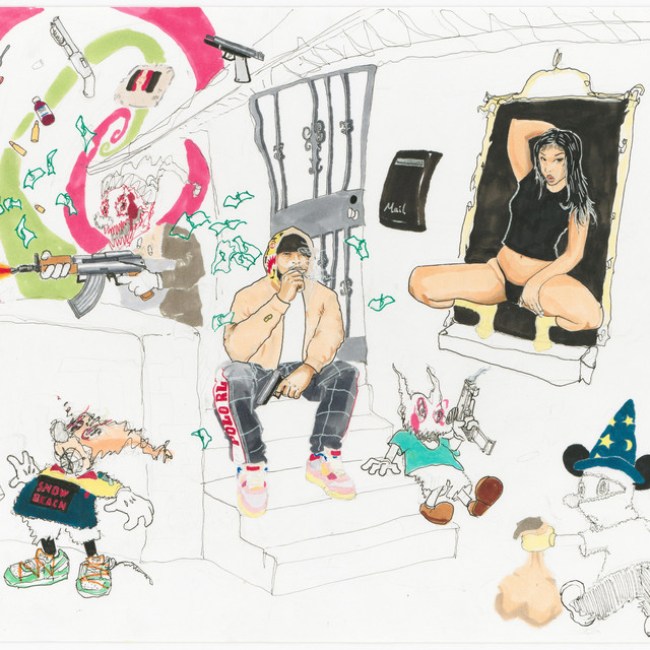

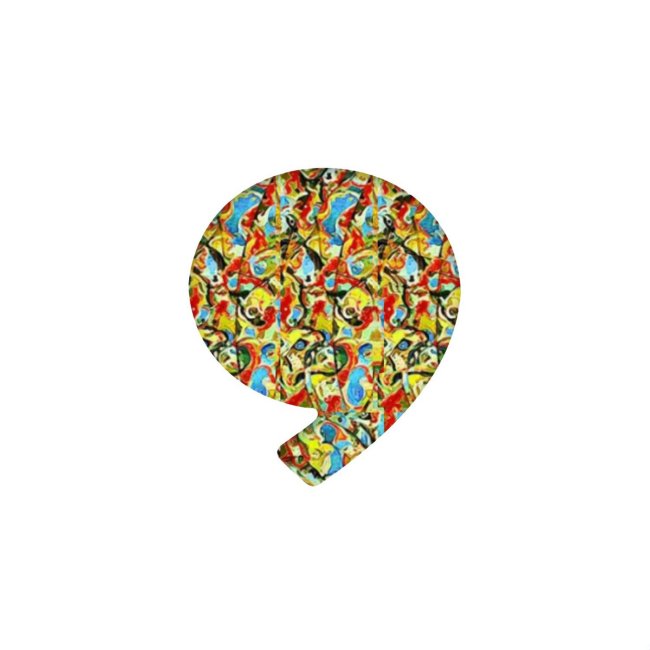

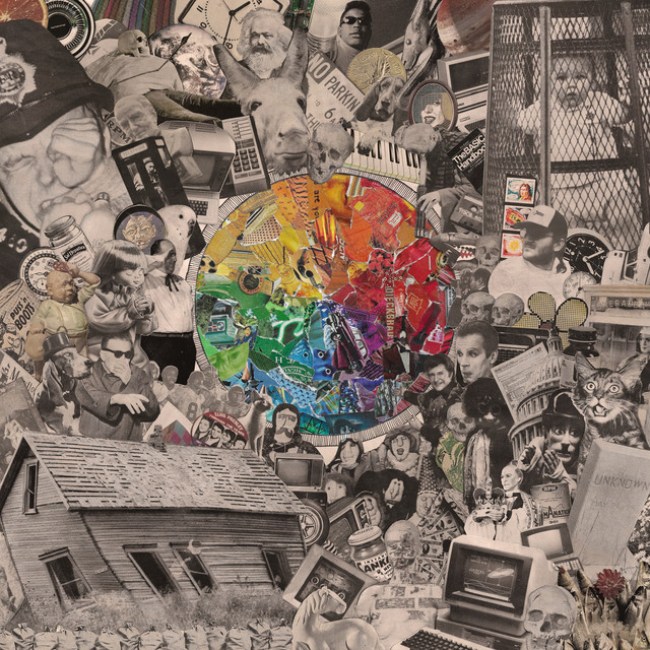

Block Music is one of two projects the D.C. polyglot released with co-conspirator GAWD this year. It often takes the form of a doodle. An idea or theme will be teased out, but not resolved. Therefore, retaining the virtue of its natal sloppiness. The album’s cover art was done by _trizm__ whose work forces you to consider the interplay between manicured control and improvisation. (He also describes himself as “Mr Trismegistus with the Midas brush” in his Instagram profile.)

WiFiGawd creates genuinely uplifting music that doesn’t collapse into empty platitudes or force you to situate yourself within capital’s metrics of success. Sequences might make you well up. It happens even when he’s only talking about exotic bales or listening to Stevie Wonder in the early morning hours. Here, GAWD’s production is covered with plugg and phonk residue. It’s executed with the vociferous Gen Z tendency to amalgamate regional influences and (Southern) mixtape heritage.

On the title track, GAWD makes it sound discordant and bow-legged on its face. Meanwhile, he’s tucking melodic threads underneath the surface tension – he loves indulging. On “Do Not Play Dis Shit”, the chords are wrestling with the drums for your attention. But on “A1 Thunda,” the chords are harmoniously cross-stitching to complement WiFiGawd’s disaffected flow.

No matter which zone of experience WiFi mines for his subject matter, you come away with a subdued joy. Not the kind that makes you splurge on shoes or pushes you to a social outing, but an incremental contentment. One that’s needed to make it through the day and keep going, year after year. – Miguelito

We’re conditioned to fear paradise. That message comes through in literary classics such as The Time Machine, and movies like The Beach and Old—where utopia is sinister and perfection is a ruse. Pearl & The Oysters (Juliette Davis and Joachim Polack) make paradise feel reachable, at least if your idea of paradise is pure tranquility. There are no gloomy corners to the couple’s sound because they simply don’t do cynicism.

That said, Coast 2 Coast does have some clear precursors: 1970s’ lounge pop, ’90s twee, and all the same artists that influenced Beach House. There are warm synths, light electric guitars, 8-bit electronics, and Davis’s gentle voice, recorded with analogue radiance. Yet the biggest inspiration has to be the sea. Davis regularly circles back to oceanic imagery– “Konami” sounds like it’s meant to be performed on a cruise ship, where Hawaiian shirts and cocktail umbrellas are compulsory. Maybe the paradise Pearl & The Oysters have created exists on an island, or in a giant bubble at the bottom of the sea, or at their “space coast lagoon.” Whatever the case, put Coast 2 Coast on when you’re stuck in traffic for immediate transportation. – Dean Van Nguyen

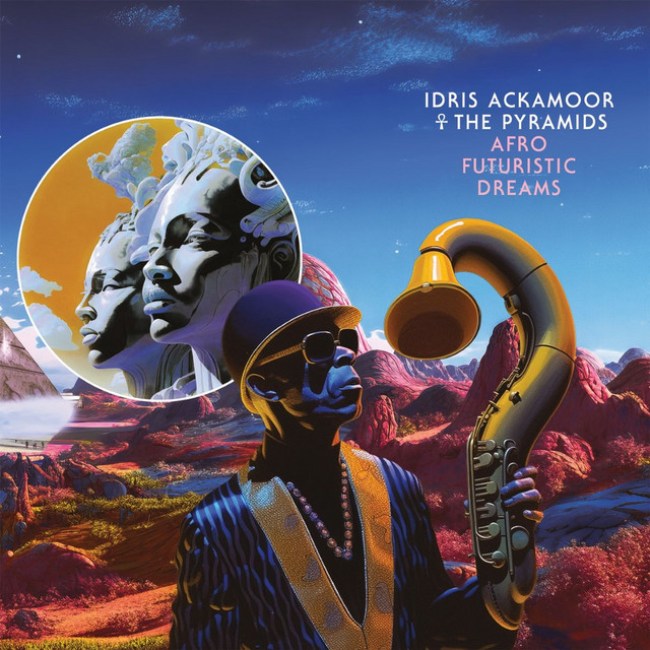

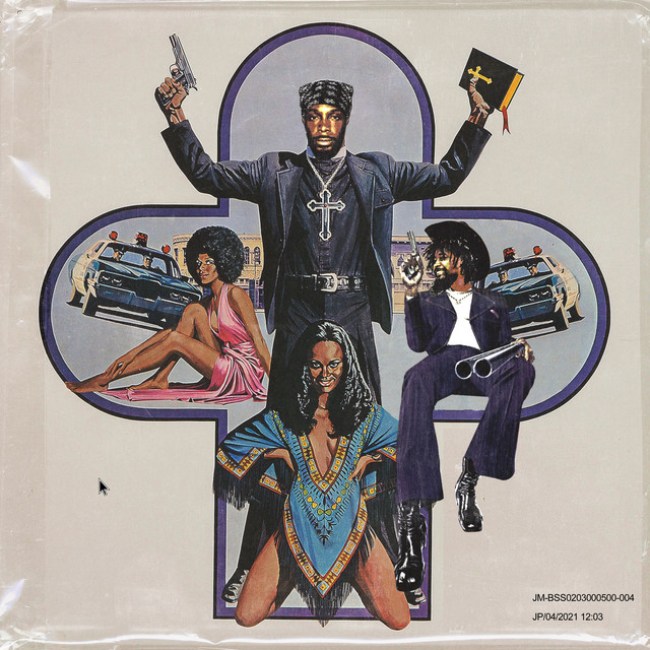

Conventional wisdom has led us to believe that an artists’ adventurous spirit dampens as the clock begins to tick faster. But the San Francisco-based, funk-jazz renegade Idris Ackamoor creates such an explosion of vibrancy on Afrofuturistic Dreams (along with his band The Pyramids) that this stereotype has never sounded so feeble.

The title track of this project transitions from the dark purr of a blues harmonica to croaky vocals referencing “trans dimensional souls.” There’s dueling synths that mirror the sheer thrill of a sci-fi anti-hero dodging enemy laser gunfire – think Star Wars if the cast was exclusively Black. It’s a bumpy ride, but Ackamoor is the perfect chaotic court jester. He creates time-warping grooves that feel like Dr. John’s “Gris Gris Gumbo Ya Ya” and “Time” by Sly and the Family Stone might have had a baby.

“Thank You God” is particularly great. Thanks to the healing gospel vocals of Sandra Poindexter, Daria Nile and Queen Califa all powerfully thanking God for his sunshine and “guiding light.” These gracious harmonies are set to an absolutely bonkers backing track. It has a glistening, Sonic 2-esque coin-up synth section and mischievous pan flutes that sound like a possessed children’s steam train. These surreal juxtapositions, between profound and whimsical, are very reminiscent of Brian Wilson in his Smile era.

Produced alongside drummer and Madlib collaborator Malcolm Catto, Afrofuturistic Dreams is proof that 72-year-old Ackamoor has no ceiling to his innovation. The shape-shifting psychedelia of “Police Dems” shows that even when he’s dipping your subconscious in acid, there’s still time for poignant social parallels. “The police cut you no slack,” he sings, “They just want you dead.”

Perhaps the best track here is “First Peoples.” It’s a celebration of Black excellence and a history lesson in how tribal drums are the true origin of electronic music. The music is ornate, but also a little dirty. It’s like enjoying the glow of a lava lap while sitting on marble floors inside the Chateau de Chambord. This record is definitive proof that Ackamoor is just as talented (and influential, given his direct influence on groups like West Coast Get Down and Sons of Kemet) as some of his more widely celebrated funk and jazz peers. He makes me less afraid of being 72 years-old. In fact, Afrofuturistic Dreams makes me wish I was 5 years younger, so I could listen to it while smoking DMT. Enjoy the trip. – Thomas Hobbs

Did the music industry annoint Sexyy Red too quickly? Can this hot streak last? The 25-year-old rap superstar from St. Louis has accelerated to the top of the charts — at about the same speed as Lou Brock. I’m sure fans of this website will remember DaBaby, his rapturous 2019 single “Suge,” and his knuckle-headed aftermath. Sexyy Red has some of that no-nonsense, blunt Southern mentality in her too. In a world where people, sometimes correctly, have new sensitivities and complexities, I worry that Sexyy Red’s bluntness and her singles will begin to fall on deaf ears.

But if we’re strictly talking about this year, then there isn’t a new rapper more ubiquitous than her. Her album, Hood Hottest Princess, belongs on a list of Southern rap albums where the track list is full of hit singles. She won’t be as whimsical as Nicki Minaj any time soon, nor rap audaciously for the nerds. But there’s no denying that “SkeeYee” is a banger. It’s everywhere: baby showers, weddings that serve mac-and-cheese as a first course, and even bowling alleys. I was on my bed when I first heard it — I sat up and started my to-do list.

One of the biggest criticisms of Sexyy Red is her unapologetic language and open attitude around sex. Those critiques only grew after a sex tape of Sexyy Red leaked this past October. But the majority of her fans seem to love and embrace her sexual prowess: “Pound Town” is for sloppy sex; “Strictly for the Strippers” is a playground chant for an all black girl cheerleading squad.

The album’s most underrated track, “Born by the River,” reveals a dark memory. Still, it reliably, unabashedly reveals explicit, sexual details. On the song, Ms. Red explains that she was selling herself for sex back in St. Louis. Whether she was making it up or not, it was the moment where I realized that Red isn’t crass just to be subversive. She’s celebrating her womanhood because it helped bring her from the precipice to the superstar she is today. – Jayson Buford

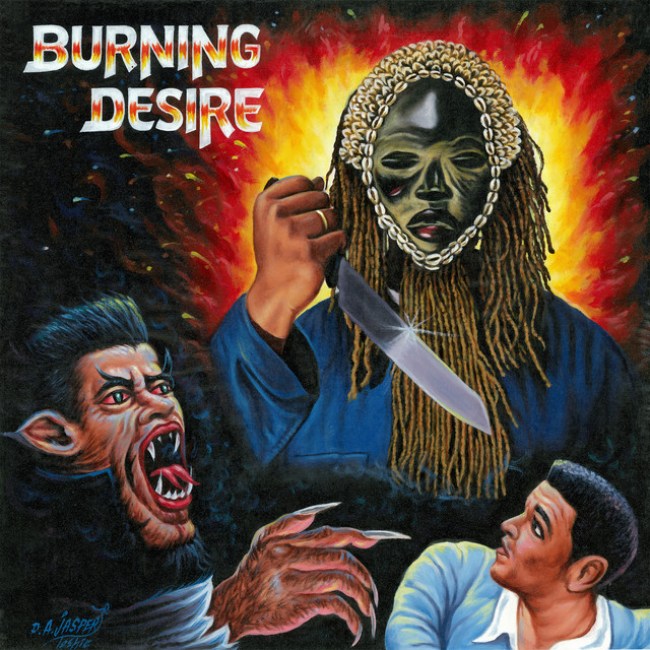

In 2023, scores of rappers have written exquisitely about grief, depression, and spiritual weight. It often occupies a spectrum of weird and compelling, to painfully dull. Michael Bonema must have noticed the way the wind was blowing on his great 2022 buzzer beater: Beware of the Monkey. It’s on this album that he promised to place among the elite of contemporary rap. And so far, he’s spent much of the ‘Year of the Rabbit’ reaching that elusive twelfth stage of mourning and spitting f*cking bars.

A strong sense of wit and self-assuredness carries the sprawling Burning Desire. Even more so, than the loose thread about the slasher-flick-inspired killer – who sports what can only be described as a Luba mask? It’s a levity and confidence that was barely detected on Disco! (2021), and sorely needed in War in My Pen (2018). Even longtime MIKE fans may have doubted his potential chemistry with Larry June (who turns “light and breezy” into fine art). Still, here he is on “Golden Hour,” politely bypassing white strippers and calling out fanfic rappers on the carpet. Simultaneously, he’s flexing in a ‘92 sedan, wearing a coat whose color is also a time of day.

As the saying goes: one shouldn’t try to fix what isn’t broken. Within that same line of logic, MIKE uses his circular rhyme patterns to explore the depths of his psyche. He adeptly navigates his way through untrustworthy former friends, while pondering the spiritual properties of cannabis.

Nowadays, as a comfortable MC, Bonema sounds like someone who’s finally found his voice. As djblackpower, he uses a variety of textures and samples to provide a sprawling 24-track backdrop for the rhyme schemes that rotate like points on an axis. It’s an interpolation of a certain (and timeless) Mary J. Blige jam. There are plenty of compositions rife with an intentionally misshapen meter — even a bit of live saxophone. Any way you slice it—beats, rhymes, or the life of an underground star—Burning Desire is the work of singularity. It reveals the outsized ambition that his fans always knew he had. – Martin Douglas

This is what you might call a: hand-in-a-Celine-driving-glove scenario. Larry June, arguably rap’s preeminent lifestyle magazine writer, teamed up with Alchemist and some of his richest instrumentals. On The Great Escape, June excels at showing the world that luxury and self-care is the best revenge against adversity. His voice is sonorous and stoned. His vibes are as chill as a cat wearing sunglasses – or a vintage Washed Out single.

The best thing about the combination of Al and June? The producer gives clarity to the rapper’s imagery. June is an enormously descriptive writer, and Al knows the chief duty of a rap producer is to make sure what’s being said takes center stage. When June ponders heading up to Seattle to golf with Jake One on “Turkish Cotton” (might I humbly suggest the PGA-approved Chambers Bay, just west of Tacoma), you can see the green for acres. The smell of salt water floats through the air when June turns off the PCH on “Exito.” And although the album is a little heavier on features than the average Alchemist-produced full length, it’s Al himself who shines the brightest on the magnanimous “60 Days.” This is where his nine-bar verse finds the perfect stylistic midpoint between two of his longtime collaborators: Roc Marciano and Action Bronson.

Rap has always been a province for the aspirational. And now, one of the art form’s leaders of wealth manifestation has created a full-length work with a producer who can painstakingly match his energy. – Martin Douglas

Listening to Fatboi Sharif is like watching a Ouija board planchette move on its own. It’s thrilling, maybe a little funny, but when the gravity of what’s being said hits you, it’s clear there’s something otherworldly afoot. The New Jersey emcee is a once-in-generation talent. He’s a brilliant writer who’s tapped into the beyond – the rap game Sutter Cane. He rhymes like a nightmarish GZA, bending his voice into a Cryptkeeper cackle or the melodious theatrics of Vincent Price sent through a nu-metal filter. It seems like Sharif was everywhere this year, grinning from the shadows like a Cheshire cat with a Glasgow smile.

Sharif began 2023 by reuniting with production partner Roper Williams. Together, they made the short but bloodshot: Planet Unfaithful. Over often drumless beats that sound clogged with dust, Sharif is a Cenobite describing all the beauty you’ll see before you die. Organs removed from autopsies get repurposed for Reanimator-like experiments, and the blood from “more bodies than Eyes Wide Shut” drips into honey. It’s woozy and delirious, unsettling but groovy.

Decay, Sharif’s Backwoodz debut, is a much starker, personal affair. It’s a triumph in his discography, an album Sharif considers his best work. Entirely produced by Steel Tipped Dove, Decay is the harsh exfoliation of layered memories, deep-seated fears, and troubling ideas about how the world actually works. Dove’s production shudders and creaks like an unholy machine, while Sharif wanders through fields of distortion and noise, searching for the truth. Decay has no antecedent, but will certainly inspire. It will sink its hooks into you, not only changing your perception of what rap music can be, but what existence itself truly means. – Dash Lewis

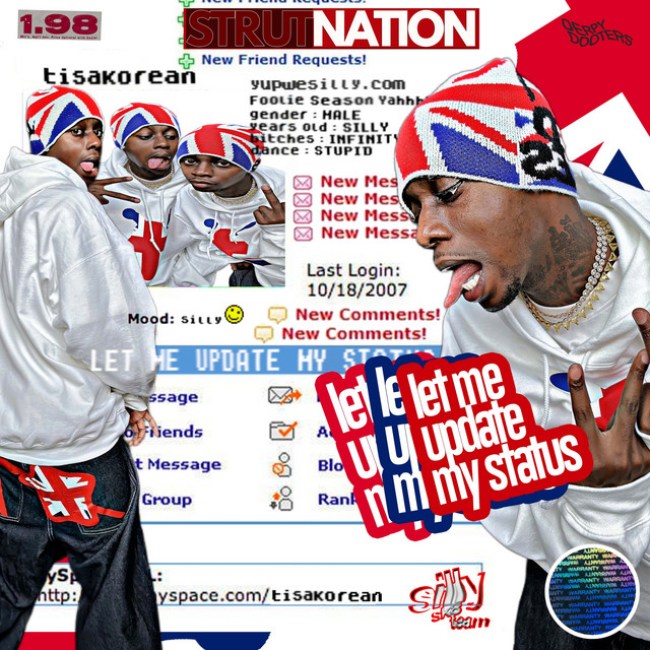

I understand that phone calls have increasingly gone out of style. However, if there’s one record that could conjure the ring and text tone nostalgia of study hall days, TisaKorean’s Let Me Update My Status is that final monument of a bygone era. In 2021, Mr. siLLyfLow and pResiLLy dove into snap and crunk, whereas LMUMS is a full-on marriage of the two artforms. It exemplifies TisaKorean’s viral unpredictability to veer into the far corners of Y2K sounds. And while the tape is rife with LimeWire-esque song titles and endless call-backs to the days of tall tees and backwards fitteds (and a literal call to action on “HeLiCoPtEr sWaG Pt4.Mp3” to “wave the tee around”), TisaKorean avoids the pitfalls of nostalgia-bait by mutating instead of shamelessly retreading. Rather, he embodies a pioneering spirit that even Soulja Boy could be proud of. He pulls this off on “SiLlY MoAn.mp3,” where the digital trilling of the snap beat and his crescendoing horniness exist in perfect harmony. Meanwhile, the relentless beeps and pings of “StUnNa sHaDeS.mp3” recreate the rambunctious bedlam of a crunk anthem – albeit with an electronic coldness that feels beamed-in from the future.

Sure, cacophonous missteps exist, but they’re complimented by the album’s quieter moments. This happens during the Anime-like serenity of “StOp tExTiNg.mp3,” and during the magnetic vocal that screws over a Zelda-OST beat on “hYpNoTiZ4.mp3.” Here, TisaKorean pulls out an occasional lean-dip-snap. It’s not an if, but a when. When all is said and done, make sure to share this with your Top 8. – Matthew Ritchie

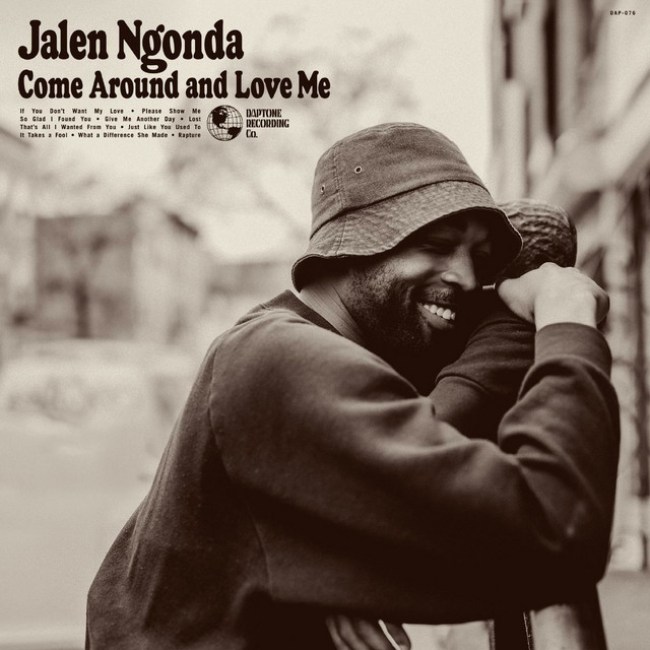

If you’re an elder silverback millennial hipster, then you definitely knew some guy who wore olive green and chocolate brown clothes exclusively and listened extensively to the Daptone Records catalog. The New York-City-based label specialized in recording and releasing new soul (and for a while, afrobeat) music. Everything sounded like it was made in the 60’s and 70’s, with analogue equipment, instruments, and a full house band of tight musicians, arrangers, and writers.

Daptone’s two biggest acts, Sharon Jones and Charles Bradley, were both middle-aged when they started recording for the label. (They both respectively passed away in 2016 and 2017.) Jones and Bradley made the Daptone aesthetic work because they lived through and grew up in that sound. Unlike the new Daptone signee, Jalen Ngonda, who was not immersed in that sound.

Ngonda is in his late 20’s, but writes music like he grew up watching T.A.M.I. show. The melodies and arrangement featured on his debut album, “Come Around and Love Me,” are stellar. It sounds like he reached into the slipstream and pulled them out of the collective funkdafied consciousness. Ngonda grew up in Washington D.C., and soaked up his father’s soul music collection. His influences range from Marvin Gaye TK and Smokey Robinson, to Isaac Hayes’ fuzz guitar flourishes, to Motown’s big string orchestration and tamborine-led foot stompers, to lowrider harmonies.

Throughout the album, Ngonda leads with a beautifully gruff falsetto that falls somewhere between Robinson and Eddie Kendricks. On “Just Like You Used To,” Ngonda yields his raw vocality to perform gospel runs, almost exclusively, about all matters of love and lovesickness. It’s all done without a hint of irony, or a record collector’s piousness. These are just great songs performed well, arranged well, and untethered from the burden of nostalgia. – Sam Ribakoff

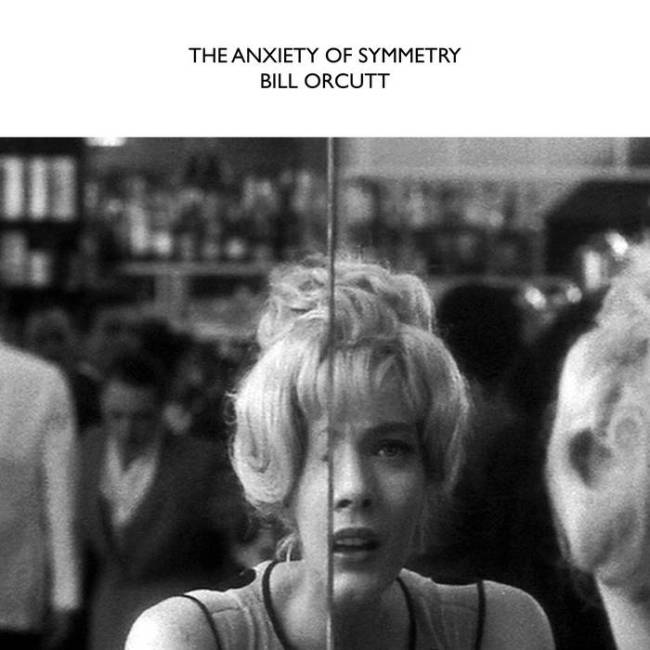

In 1997, Harry Pussy broke up. The Miami noise-rock outfit presented an everything-at-once car-crash of punk rock, armed with shattered drumsticks and a well-worn copy of Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come. Almost immediately, Bill Orcutt—a guitarist and vocalist in the group—started digging through the wreckage. In 1998, he collaborated with Adris Hoyos, the just-disbanded group’s drummer and vocalist, isolating one second of her screaming and stretching it across an hour of vinyl. If Harry Pussy’s music was about the white-hot sound of a million notes at once, Let’s Build a Pussy is about zooming in to find something remarkably similar: A slow-motion drone that achieves infinity through countless microscopic variations.

Let’s Build a Pussy proved indicative for Orcutt. There, he took a singular sound in American rock-and-roll and reimagined it, honoring the spirit of Harry Pussy by pulling the rug out yet again. Since then, he has done the same with all sorts of musical traditions: the Great American Songbook, improvised music, American primitivism. In 2020, he released Pure Genius, a half-hour of broken-down synthesizer scales and a man counting from one to six; the following year, he put out A Mechanical Joey, looping Joey Ramone’s count-offs—one to six, again—and building a steamroller of punk-rock avant-minimalism.

The Anxiety of Symmetry, Orcutt’s latest computer-music curiosity, extends that approach further. On its face, the concept is identical: Human voices counting from one to six, stretched and looped and chopped into something far greater than the sum. Here, though, it’s a series of female voices scattered into infinity. Throughout the record’s two pieces, harmonies emerge and disappear on a moment’s notice; voices stretch into generous tonal beds while others maintain their momentum, counting over each other until the words are hardly discernible. This is polyphonic chant for the MIDI era; it’s Steve Reich remixed by Orange Milk. Nearly twenty-five years ago, Let’s Build a Pussy took a moment and twisted it into a Möbius strip. The Anxiety of Symmetry pulls off the same trick with computerized—and choral—music, achieving a frenzied beauty by refracting the history of twentieth-century minimalism into a tonal blur. Now that’s punk. – Michael McKinney

An accomplished techno producer and dance music DJ, Avalon Emerson is known for balancing thoughtful taste with big emotional payoffs. She’s not afraid to raise eyebrows with unexpected moves, like covering a Magnetic Fields indie-pop tune in her 2020 DJ-Kicks mix or mixing Alice Deejay’s dance-pop smash “Better Off Alone” into a set at Berghain’s Panorama Bar. But Emerson takes an even bigger creative risk on her debut album, stepping away from the dance world that made her a success to explore a slower-paced style of dream-pop.

On & the Charm, Emerson dials back the intensity of previous heaters like 2015’s “Constantly My Cure (Vocal Mix)” and 2016’s “Dystopian Daddy.” Album opener “Sandrail Silhouette” instead sounds like something off the My So-Called Life soundtrack, with jangly guitars and hooky orchestral strings buoying lyrics about aging and passing time.

Emerson still shows an innate sense of groove across the album—consider the interlocking shimmers of “Dreamliner” or the gentle whipping snare of “Astrology Poisoning.” But the beats and synths are tempered with calming dollops of reverb and echo. For the most part, Emerson lets her plainspoken singing and wistful lyrics take the lead. “But I’ve been fussing with this here melody too / Coming together like glue,” she muses in “The Stone.” It’s a molasses-thick synth ballad where her impressionistic lyrics contrast the busy repetition of nightlife with the quieter pleasures of songwriting. It’s tracks like these that make & the Charm perfect for long drives and driftless daydreams. – Peter Holslin

Sam Wilkes’ DRIVING is his first indie rock record. However, everything the jazz bass giant concocts nestles itself into its own universe entirely. Sounding something like Wilco taking on the catalog of Jaco Pastorius, DRIVING is a bucolic collection of straight-ahead folk-rock songs flipped on their head. It’s paired with sound collages that spontaneously coalesce into pop jams. Throughout the album, Wilkes uses skills and sounds often reserved for his jazz collections – with frequent collaborators like Sam Gendel, Jacob Mann, and Louis Cole. Repetitive phrasings create a base layer of comfortability, allowing Wilkes and his buddies to tweak rhythms, melodies, and modes with an improvisational spirit.

“Ag” sounds like Sparklehorse scoring a 50s melodrama (think Doug Sirk), with lush string swells bumping against a kitschy electronic drum machine and Wilkes’ warbling vocoded voice. On “Own,” the LEAVING Records alumni recruits the aforementioned pop-jazz maestro Louis Cole, where the duo croon over gentle acoustic guitar patterns. Pulsing strings signal a key change from the pleasant opening to something far more ominous. It’s within this switch, though, that Wilkes unveils one of the album’s strongest melodies. It’s tucked into the fabric of the song, less a focal point than a cog in this brilliantly designed machine. Sam Wilkes is one of jazz’s great sidemen and composers, but on DRIVING he makes his case as a pioneer of an indie rock renaissance. Little moments continually unfurl into big ideas. Like all great artists, Wilkes is informed by his favorites and forebears, but from an unexpected vantage point. He’s telling a truth but telling it slant. – Will Schube

Of all the guitarists who emerged from the musical traditions of Sahel cultures – the lysergic virtuosity of Mdou Moctar, the uncompromising reclaim of the Touareg songbook of Etran de L’Aïr, the serene melodicism of Abdallah Oumbadougou, even the jazzy undertones of Fatoumata – Bombino is the hardest to pin down. Still, he manages to squeeze the most soul and emotion out of his psychedelic guitar.

In Sahel, his most personal and politically critical album yet, Bombino exudes effervescent melodies, cathartic phrasing and a lot of heart. He does this while telling us about the pain of unrequited love, the atrocious treatment of his people by the State, and above all, the eternal journey of the Touareg peoples.

Sahel also shows us a Bombino more committed to creating songs with greater structural balance, beyond the immersive and improvisational nature of his tradition. His goal is to create pieces that survive over time; as if he’s determined to leave a legacy. Therein, creating a home in which Touareg music can return. – Leonel Manzanares de la Rosa

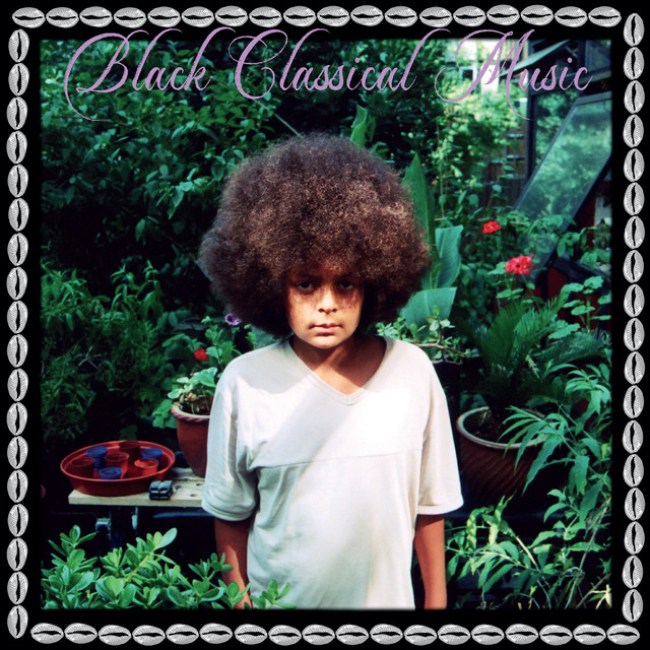

As Yussef Dayes himself is quick to point out, he isn’t the first person to use the term, “Black Classical Music,” with legends such as Miles Davis and Nina Simone having employed the term to describe their own music. Dayes, however, puts his stamp on the all-encompassing phrase with his “official” debut solo album of the same name: Black Classical Music. He touches on damn near every aspect of Black music of the past century, from contemporary hip-hop to Caribbean beats to space aged Astro funk.

For anyone with even a passing knowledge of the London jazz scene of the last decade or so, Dayes is a familiar name. You might recognize his work with Kamaal Williams in the aptly named Yussef Kamaal or maybe his work with Tom Misch — not to mention a string of burners with his own Yussef Dayes Experience. On BCM, though, Dayes wears a slightly different cap, providing a clear vision as band leader and musical director in this portrait of modern jazz. Working with longtime partners-in-crime Rocco Palladino (bass), Charlie Stacey (keys), Malik Venna (sax) and Alex Bourt (additional percussion), Dayes elevates the album’s musicality with additional heavy-hitters Shabaka Hutchings, Leon Thomas, Chronixx, Masego, and the aforementioned Misch, among others. Even Dayes’ daughter Bahia makes an appearance on ethereal “The Light,” cementing the album’s familial and autobiographical vibes.

While much has been made of the album’s length and pacing (19 occasionally disparate tracks clocking in at more than 70 minutes is not a quick listen), not nearly enough has been written about Dayes’ vision and talent dripping from each track. (You don’t even need to know what a paradiddle is to recognize it.) Now, it’s near impossible to pick the “best” joints here, but standouts certainly include: the eponymous, smoking opener with Charlie Stacey’s energetic keys that ranks among the fiercest jams of the year, the bass-heavy groove of “Rust,” the reggae-tinted “Pon Di Plaza” and the stringed beauty of “Magnolia Symphony.” While each track follows its own groove, Dayes maintains a warm and relaxed energy that holds the album together. For those reasons and many more, “Black Classical Music” is a classic in its own right. – Chris Daly

San Antonio’s Alberto Calvo made what’s known as the first rap record to come out of Texas. The late Spanish language radio personality went by the name “Disco Al” when he pressed “The Bounce Rap” in 1980. He enlisted the help of Barrio Sound Band, whose samplings can still be found in the Frontera Collection. “The Bounce Rap” shouts out George Gervin, doesn’t hold punches against wallflowers and rhymes “Daffy Duck” with “not giving a f*ck.” Even if rhyme schemes stay consistent, flexes change over time. Disco Al boasted he didn’t “need an automobile,” but you’d never hear HOODLUM, or any self-respecting rapper from the South make that claim today.

On SOUTHSIDE STORY, HOODLUM speaks of Ghosts, Tahoes and chameleon paint jobs. The most compelling aspect of HOODLUM’s music is how his voice and production blend to distort time. There are no clear breaks between tracks or sense of length when listening to SOUTHSIDE STORY – unless you constantly check the song titles like a narc. You shouldn’t be able to name a favorite HOODLUM track if you’re listening to him properly. That also shouldn’t hinder praise. He raps in a whisper that’s easy to misclassify as haunting, when really it’s more of an oil slick effect – partly caused by his never-absent grill. He’s not trying to scare or soothe with his inflection. It assumes the character of an internal monologue, like we’re not supposed to be listening to these songs. If cynicism drives you to seek “focus tracks,” then listen to “PRESSURE.” On this track, he nestles into the pocket like the nugs resting at the bottom of his turkey bags. Or maybe “GROOVE,” if you want to get drawn into a whirlpool of sensation and Magpul furniture. In order to meet SOUTHSIDE STORY on its own terms, you’ll need to set aside 45 minutes just to listen. That way, you can fully appreciate one of San Antonio’s sole gonzo prophets. – Miguelito

London born-and-bred keys man Kamaal Williams was always the unlikeliest of jazz touchstones. His breakthrough album with virtuoso drummer Yussef Dayes, “Black Focus,” took a kitchen sink of influences and reduced them to a lethal funk that evoked grime, dubstep, house and jazz while managing to sound precisely unlike any of them. Stings, his third solo album since helping kickstart a golden age of London jazz, sees him push the extremes of 2020’s Wu-Hen, swerving between genres with the abandon of a faded late-night drive.

On the one hand, he’s still swimming in formative sounds. “The Guvna”’is stuttering Clavinet funk that recalls his work with Dayes. The title track, “Stings,” is a cover of Soho’s 80’s house classic: “Hot Music,” which seems thrown in for the sheer hell of it. “Dogtown” and “Repercussions” are down-tempo dance tracks that nod to his notable broken-beat work with producer Wu-Beeza. On the other, he finds pockets of hushed beauty. “Little River” is a Rhodes dreamscape with whispers of saxophone that wouldn’t be out of place on Andre 3000’s flute album. As well as the piano improvisations on “Magnolia” and “Taiwan,” that conjure the spirit of Ryuichi Sakamoto – the latter features a haunting performance by American violinist Stephanie Wu.

The final tracks on the album culminate into a final crescendo. On “The Last Symphony/ Magnolia,” Williams takes the mic over a grandiose Miguel Atwood-Ferguson arrangement, unbowed in the face of personal setbacks. He then closes with the swaggering grime workout “PKKKNO,” traveling between Mecca and Paris fashion shows within a single “cocaine hoes” verse. Little of this will please those still hankering for the cohesiveness of Black Focus, but for everyone else, Stings is an insouciant and timely rejoinder to a London jazz scene that’s verging on respectable. – Joel Biswas

Chelsea native YL is one of New York’s finest miniaturists, collapsing stacks of images and memories into dreamy 90-second collages. On Don’t Feed the Pigeons, his seamless transitions yield a work of impressionistic autobiography. Timelines are blurred and refracted until the past and present feel interchangeable. On this album, YL frames his reminiscences within the broader sweep of history, his deconstructed anecdotes brimming with trademarks and touchstones. “The Proof” connects discrete moments with irreversible outcomes. Like when YL uses visual recall, it’s shorthand for persistent grief: “I seen Cam at the Knicks game the night my aunt died, it was rain/Shit ain’t the same, but we live with the pain.” On “Good Numbers,” Jadakiss and the bygone 125th Street mixtape market are inflated to near-mythic proportions.

Throughout the album, YL raps in breezy, double-tracked drifts. His vocals wash over Eyedress and Roper Williams’s delicate instrumental layers. Soul samples snake around muted drum patterns. And at times, the mournful loops clash with YL’s odes to designer brands and Roc-A-Fella triumphs. The album’s nostalgia is rinsed in sandstone grays, snapshots compounding one another, nodding to time’s incessant march. Sequenced consecutively, the standout tracks: “More Life” and “Play Dead” distill the record’s push-and-pull suspension. It’s a limbo between youth and adulthood, action and regret. YL’s obsession with Y2K culture is a last-ditch effort to recapture what’s lost – a phantom limb’s insatiable itch. – Pete Tosiello

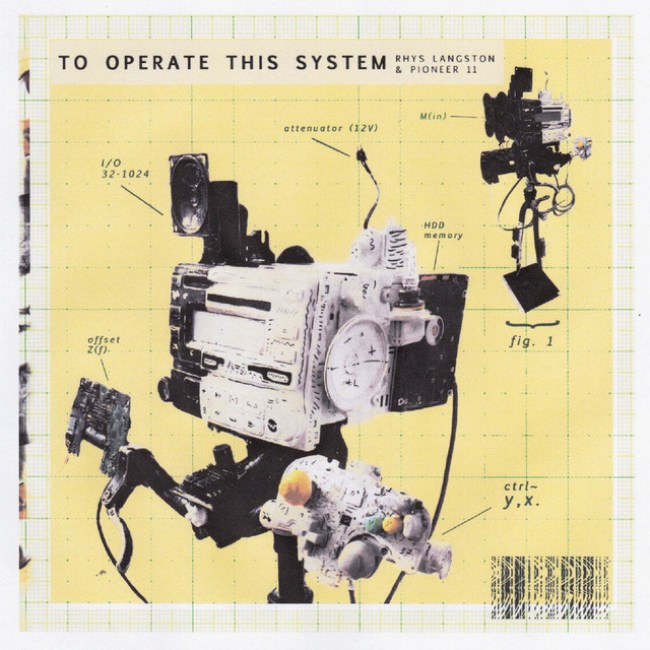

Pioneer 11 and Rhys Langston have achieved techno-human symbiosis. The POW Recordings trio—undeterred by the rapid displacement of musical creativity with webs of algorithmic datasets—have fused together the essence of psychedelic space dust and clarinet. The final product? An apex of humanist electronic music called: To Operate This System. This album is the first collaboration between the labelmates, and is adorned with a sculpture of technological nostalgia. It was crafted by Langston with a series of old video game controllers, a car radio, and a welded bike frame, amongst other gadgets, and symbolizes their symbiosis—mechanization molded by human creation.

Seizing production means from the computer, To Operate This System was recorded live through a series of jam sessions. It came after the first link-up between the three surveyors at a Dublab POW Showcase back in 2018. The notion of human and technological separation guides the project,rejecting computerization while simultaneously embracing live electronic sounds and loops. Despite the technological basis of the music, it has an authentic cohesion that can only be brought about through live sessions. Whether they are lamenting the cosmic exploits of Langston’s tabby cat Tahini or making a quick DoorDash order to the Basilica, the LA-based trio have created a system of their own. It’s a project made for all to witness and enjoy—powered by lasers and recorded live. – Kevin Crandall

Millennials all over the world rejoiced when, in 2021, a British 20-year-old named Victoria Walker released her debut mixtape as PinkPantheress, To Hell with It. Finally: Here was another artist in the vein of Grimes who could bring back the short-lived, dearly missed, era of Y2K – maybe this time for good. Born into a high-definition world, Walker sounded familiar with, if not completely tired of, its many bugs and quirks. Her plainspoken, sing-song delivery seemed out of sorts with the speedy jungle and garage breaks that cratered underneath. “I never wanted to cast doubt in your mind,” she sang, batting her eyes over a Crystal Waters flip.

Two years later, it’s nice to see her vision of a pre-9/11 world still pay off. Like To Hell with It, Heaven Knows is rooted in Y2K-core and Walker’s worrisome thoughts. From the moment a pipe organ booms in opener “Another life”, despair creeps over her. “I just had a dream I was dead / And I only cared ’cause I was taken from you,” she sings in “Mosquito”, a highlight in a record full of them. The few features delight: Central Cee is the brooding counterpart to Walker in “Nice to meet you”, while Kelela is the mentor showing her the light in “Bury me”. Throughout Heaven Knows, Walker weeps of unrequited love and eternal darkness. The production – she’s credited on every track – is lithe and colorful, jumping from drum ‘n’ bass to drill and pop rock. The combination of it all makes you wonder if she’s deadly serious or totally joking. In other words, it’s soft-goth as hell. – Miguel Otarola

After more than a decade crafting legendary cuts for French Montana, Curren$y, and the late Lil Peep, super-producer Harry Fraud has a fresh muse in Chicago rapper Valee as evidenced in their collaborative album, Virtuoso. This is Valee’s second full-length project; for Fraud, it’s the latest collaborative tape in a long career of formidable discography. Running just under half an hour, Virtuoso has a laissez-faire flow to its 11 tracks, with the two artists pushing their signature styles and, in turn, alchemizing serious creative chemistry.

Fraud’s beats are tailored to Valee’s coyly confident presence, as the producer fills in Valee’s sparse verses with lively samples and swirling arpeggios amid dreamy melodies and hefty basslines. Dryly delivering references to Martin Scorcese and WALL-E, Virtuoso sees Valee commandeering the quiet eccentricity of his style over some of Fraud’s most varied and ambitious songwriting.

The ethos of the whole project is, put simply, just guys being dudes. There’s a relaxed familiarity to tracks like “Watermelon Automobile” and “Uppity”, tempered by Valee’s softly shamanic discussions of hedonistic activities and vehicles. Valee’s sophomore outing showcases the MC stretching his technical capabilities while honoring his stylistic muted demeanor, lifted by the dramatic flourishes of Harry Fraud in mad-scientist mode.

Features from some of Fraud’s collaborators such as Action Bronson and RXKNephew present new opportunities for Valee to showcase his originality, while Chicago rappers Saba, Z-Money, and Twista all guest star and shine a light on Valee’s roots from his start as a G.O.O.D. Music signee to his role as a generational tastemaker of Chicago’s long-standing legacy in groundbreaking hip hop. – Staley Sharples

“There is no cure for a broken heart,” is one of the ancient truths chanted by Pakistani-American singer Aroof Aftab. This appears on “Shadow Forces,” where Aftab sings in her native Urdu dialect. Thanks to the unpredictable keys of pianist Viyja Iyer (that balances both ominous and serene), and Shahzad Ismaily’s thunderous synths, Aftab’s vocals hit like tender wisdom, emanating from the bowels of a pitch-black cave. It’s Colonel Kurtz singing a lullaby.

The highlight from this three-piece collaborative album, Love In Exile, is this: beauty emerges from a state of decay. The album gives you enchanting ghostly harmonies that feel more like timeless prayers than reactive lyrics. Rarely have three musicians sounded so in-tune with each other, both emotionally and physically. This happens on “Haseen Thi,” where the bright tremble of a xylophone and wave-upon-wave of muddy bass notes create the image of cleansing yourself while floating on tranquil water.

“What was the secret that I kept silent in my heart?” howls Aftab like someone unimpressed with their own shadow. This lyric prompts the listener to question their hidden shortcomings and lies. Now, on Love In Exile, Aftab’s otherworldly hum serves as a balm. Especially, if you feel like you’re looking into an abyss and need a guiding light. Alongside Iyer and Ismaily, Aftab has created the musical equivalent of an emotional reset, and an experimental jazz record capable of plotting a route out of a fog. – Thomas Hobbs

For every visionary artist who built a world out of kung fu flicks or kaiju movies, there were twenty more who burnished their mystique by sampling Al Pacino’s tragic Cuban émigré. Gangster movies provide rappers with off-the-shelf metaphors and themes. Roc Marciano and Jay Worthy exist to sidestep trite simplicity, so they have to dig deeper than their peers for references.

Three years after Jay-Z styled himself the American Gangster after a Ridley Scott blockbuster, Roc Marci reimagined New York rap as a grimy and at times psychedelic diary of the underworld. Roc resembled Superfly and Black Caesar in his boasts more than any Hollywood archetype. An entire scene would grow from his 2010 debut. Jay Worthy similarly built a career out of avoiding stylistic cliches. An avowed West Coast Piru, he traded the funky worm for hard 80s funk.

Coming together, Roc Marciano and Jay Worthy bend the rules of West Coast gangster rap. Their collaborative album alludes to The Program, a sensationalist 1993 sports drama, rather than the gangster movie du jour. The parallels between gang life and Division 1 football aren’t obvious, but they’re there: the mania, the glory, the brutality, the cultish obeisance to the team.

Jay Worthy depicts desperation, bloodletting, and opulence in flashes, not grand cinematic arcs. His vignettes live on Roc Marci productions that span different levels of oddball. If guests like Kurupt, Kokane, and Jay 305 find the sparse, drumless tracks unwieldy, they don’t show it. Nothing Bigger Than The Program comes from two auteurs who can subvert tradition because they’re steeped in it. – Evan Nabavian

In a (better) world, where BigXthaPlug’s “Texas” could be a worldwide hit single, you can picture state luminaries Miranda Lambert and Beyoncé calling him up to ask if he’s interested in doing a genre-fusing remix. The tune might hit enough local references to make it a Lone Star anthem—with a steel guitar more Texas than Tim Riggins eating chicken-fried steak—but such things are worthless without an effective diplomat at the helm. Thankfully, BigXthaPlug invites comparisons to Scarface, and not just because he’s a technically flawless, furnace-voiced behemoth from Dallas, but because the blues is imprinted on his soul.

Across breakthrough project AMAR, BigX is assisted by a set of beats splashed with brass instruments, pianos, even an Erykah Badu sample, forming a warm, musical set analogous to what another southern Big was doing a decade ago—Big K.R.I.T. At the heart of album are the DJ Screw-indebted “Bacc to tha Basics” and hi-hat-riding “Safehouse,” a showcase of naturally percussive rapping, pure confidence, and perfect referencing. And any strip club in Texas not playing the addictive electro-bop of “Thick” every night needs to fire their DJ. There are few overarching themes here because sometimes the only trend worth setting is love for your home soil. – Dean Van Nguyen

In the last few years, ghazals have begun winning Grammys, taking up tent space at Coachella, and generally permeating more of the airwaves across the Western hemisphere. The tragically romantic musical tradition, long popular in South Asia, has made these contemporary inroads in large part thanks to singers like Ali Sethi, who’s radical modernization of the form has helped draw out its latent connections to pop music. The Pakistani artist’s trained technique brushes up against his omnivorous influences and inherently groundbreaking queer identity to show how artistically adaptive and uninhibitedly sensual the genre can be.

No more so has he challenged the perceived limits of ghazals than on Intiha, his masterful reimagination Nicolas Jaar’s adventurously ambient 2020 record Telas. Their collaboration emerged organically from Sethi’s quarantine project of publicly riffing over Telas instrumentation, leading Jaar to invite him to conduct a formal overhaul in which song fragments old and original were twisted into an entirely new product. The novel juxtaposition of percussive trance, rave, and dub sounds with the tender longing of Sethi’s searching vocals and ragas realize stunning melodies that feel simultaneously meticulous and wondrously wayward.

You can hear each artist reveling in the seemingly dichotomous approach of the other, filling in gaps they might have never otherwise heard in their own music. The result is sonorous and complete, pathbreaking while as immediate as anything either has worked on in the past – from the syncopated folk stomp of “Muddat” to the dense harmonies reawakening Mirza Ghalib’s words on “Dard.” Under their stewardship, the ghazal renaissance is seemingly just beginning. – Pranav Trewn

As a Deadhead who was 12 years old when Jerry died, I am less prone than others to judge fans for venerating the past. I caught Outkast several times at the height of their powers, yet I’d prefer to have seen even a sub-par Brent show from the late 80s. There is no substitute for live improvisational music. It is one of the few things in this era of digital upheaval that validates my (rapidly diminishing) faith in humanity.

But none of the many non-Dead jam bands I have seen live have done more than capture my fleeting attention, until I wandered into one of the initial Taper’s Choice shows at Gold Diggers in East Hollywood last Halloween. Finally, a psychedelic band with its own sound, who shred without taking themselves (too) seriously. At their best Taper’s Choice evokes the ethereal sensory deluge of a late 70s Dead show, minus the excesses that turn civilians off that scene.

Are these independently successful musicians serious about this little jam band, or is it just for kicks? Their initial release, History of Taper’s Choice: Vol. 1, nods at the former. There are the mind-melting, soaring jams of Hieronymus Bong and Lick the Toad, but also tight, radio-friendly songs that evoke Blur or Revolver-era Beatles. The band’s identity coalesces over the series of shows and studio sessions that produced this mixture of live and recorded tracks, a raw but promising statement of potential.

The standout track is the acoustic “21 Miles”, which suggests there might still be an American Beauty in this band’s future. What we need is simply more: more shows, more songs, more harmonies, and longer sets so we can witness in person as the band continues to plunge deeper into its weird and promising sonic universe. – Gautham Nagesh

At this stage in his career, it’s less a question of “will the new Open Mike Eagle album slay?” and more, “just how many will lay slain in the wake of Open Mike Eagle’s latest?” On his ninth master class, Another Triumph of Ghetto Engineering, OME lays further claim to the most consistently solid rapper in the game today.

Mike maintains a self-reflective tone throughout the album, analyzing everything from a schoolboy crush on Apollonia to reminiscing about Grandma. Tracks are structured around samples and loops that recalls high school projector film soundtracks. “a new rap festival called falling loud” is a literal instruction on what to do with his earthly remains, while “Dave said these are the liner notes” and “we should have made otherground a thing” continue in the great shoutout tradition of Digital Underground’s “Good Thing We’re Rapping.” While billed as an OME album, AToGE often plays as a crew piece with familiar faces scattered throughout the tracks, including longtime homies Video Dave and still rift, as well as cameos by older associates like Blu and Daddy Kev (not to mention one of the better verses dropped to date by Eshu Tune/Hannibal Burress). “the grand prize game on the bozo show” and “WFLD 32” rank among the top posse tracks of recent memory, full stop. – Chris Daly

After a hellish half-decade of persecution and imprisonment by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, 03 Greedo took to DSPs the very same night that they updated his scheduled release date: “Y’all say Greedo free ’til it’s backwards, so that’s what’s next.” What better way to reintroduce the world to the pioneer of creep music than a surprise release sneaking up on you out of nowhere?

Mike Free plays the role of both an executive producer and a ringside announcer on Free 03. The producer behind “Rack City,” “HeadBand,” and “I Don’t F*** WIth You” employs “Bigga Rankin Intro” as a reminder that 03 Greedo was too headstrong to ever lose his mind and spirit in the fight for his freedom, despite the losses his cell walls couldn’t defend against. Greedo honors the artists he was forced to mourn in solitude, including his kindred spirit Drakeo the Ruler, Nipsey Hussle, PnB Rock, Young Dolph, and Takeoff.

If it weren’t for the static of his jailhouse recordings on “Today,” “Hype,” and “If I Die,” it’d be almost impossible to discern when Free 03 was recorded. “Drop Down” injects the sliding 808s from New York drill, popularized in 2019 by Pop Smoke, alongside instructions on how to throw that a** back from Houston’s KenTheMan, a member of 2022’s XXL Freshman class. Even “I Can’t Control Myself” with Ohgeesy rekindles the pair’s tendency to get love-drunk, with squealing synthesizers bringing you right back to 2018’s “Floating” on God Level. In spite of the 20 year sentence that loomed over his head everyday in the Middleton Unit in Abilene and later the Havins Unit in Brownwood, Texas, Greedo has only gotten richer, riper and more refined in the five years he’s been away (Cue: “Bacc Like I Never Left”). – Yousef Srour

For producer and singer-songwriter Jessy Lanza, her career trajectory evolved when she moved to Los Angeles in 2022, and gained a confidence that was hard to come by in her hometown. Growing up in Hamilton, Ontario she was often labeled too sensitive, but on her latest album, she propels these sensitivities through rich analog textures and a soft falsetto.

Lanza wrote her fourth album, Love Hallucination, a bolide of dancepop bliss. At times, the synth-heavy instrumentation and uptempo drums can feel akin to LA’s modern funk – see “Limbo.” In the playful video for the album’s opener, “Don’t Leave Me Now,” Lanza sprints through streets of her new hometown amid crawling traffic, stopping at beacons of rest while paparazzi loom in the shade.

Since she first began releasing music a decade ago, Lanza hasn’t shied away from innovating. Learning to tailor her vocals into the music she wanted to make took time, and she’s cited Lifestyles of the Laptop Café by The Other People Place as a touchstone of inspiration for this. To perform the saxophone solo on “Marathon,” she recently began touring with an EWI [electronic wind instrument] – a continuation of her former days playing woodwinds in jazz and concert band.

Influences can be traced to Janet Jackson, China Crisis, and DJ Rashad, but Love Hallucination is a sun-bleached distillation of Lanza’s personal experiences – the triumphs amid battles – as much as it’s a club record. On “I Hate Myself,” Lanza repeats the track title like a cathartic mantra. It’s a stripped down nod to Prefab Sprout’s “Wild Horses,” and moments like this bear witness to the honest self-examination at play. – Evan Gabriel

To the undiscerning listener, Sufjan Stevens has long been an avatar for spare, sad indie music. It’s an almost comical oversimplification given, say, the gushing theatrical ambition of 2005’s Illinois, or the anxious electronic architecture underpinning 2010’s The Age of Adz. But it’s true that Stevens has long been one of our best communicators of grief and despair. Namely, Carrie and Lowell, his landmark 2015 album, paid tribute to his mother and stepfather and excavated his childhood in uncommonly candid ways.

On that album and again on his latest, Javelin, Stevens writes unblinkingly about inconceivable tragedy. The album is dedicated to his late partner, Evans Richardson, who died in April. Later in the year, Stevens was hospitalized with Guillain-Barré syndrome, a rare muscle disorder; in the wake of that diagnosis, he had to enter physical therapy to learn how to walk again.

That backdrop suggests a punishing listen, but, for all its weight, Javelin is Sufjan’s most life-affirming work to date. “Will Anybody Ever Love Me?” is as devastating as its title, but it ends at an unlikely register, unfurling into a euphoric and kaleidoscopic swirl. “Shit Talk”, maybe the most astonishing moment on an album full of them, climaxes with Stevens chanting “No, I don’t want to fight at all” endlessly, the wounded, conciliatory inversion of his infamous “I’m not f*cking around!” explosion on Adz. Stevens doesn’t shy away from ugliness, as in the blood-stained title track, where he grapples with unspeakable impulses. But the miracle of Javelin is that Stevens, steeped in unimaginable tragedy, can walk away with so much hope. – Alex Swhear

Who would’ve thought the most shocking thing you could do in music in 2023 was to break out the fucking flute?

For Joel Danell – a Swedish film composer who records under the name Sven Wunder – showcasing the flute on his fourth album, Late Again, was a given. “It’s like, my favorite instrument,” he told me in an interview months before André conjured his New Blue Sun. The flute’s breathy, dazzling sound fits right at home in Wunder’s world of jazz, lounge, and piano etudes. It’s different terrain from what Wunder has previously covered; compared to the Turkish grooves of 2020’s Eastern Flowers, the luxe orchestra and swing band arrangements of Late Again are more evocative of a romantic winter night in Paris or London.

By reinvigorating the sounds of a bygone era – one of spaghetti Westerns, ballroom dances, and smoky cafes – Late Again sets out to achieve a sense of timelessness. After all, when was the last time anyone heard of “easy listening” aside from the poorly tended section of a record store? Even song titles like “Pop-Jazz Structures” and “Jazz At Night” come off as nods to the functional “library records” that accompanied television shows in the ‘60s. Make no mistake: This is the original music. A swing band crackles to life in “Stars Align” while strings scintillate the air in “Take A Break”. Wunder winds down the record with “Asterism Waltz”, a ballad led by a twinkling guitar. It is one of the most beautiful songs of the year. Oh, right – there are flutes all over the album. Wunder will make you fall in love with them, too. – Miguel Otarola

“Erotic Probiotic 2 was done with a budget of $0 put on a 2 person run (half black owned) indie label in South London called Scenic Route.”

This tweet by Nourished by Time AKA Marcus Brown from early December nicely wraps up their accomplishments this year.

With Erotic Probiotic 2, Brown’s debut album as Nourished by Time, they offered a gratifying, contrasting mix of lo-fi recordings and incredibly rich songwriting, drawing from ‘90s R&B, oldskool electro, synth and guitar pop.

As the tweet suggests, there’s a sense of barebones, DIY craftsmanship to these nine songs. And there’s another beautiful component at work here: the interplay of familiar sounds of the past, who have often been used as pastiche or satire, and the absolute earnestness of Brown’s crooning and lyrical content. Dām-Funk or Dev Hynes come to mind, both artists who often saw themselves forced to let people know that funk and R&B are indeed serious business. While Brown’s first outings were more guitar heavy, Erotic Probiotic 2 finds them heading straight to the dancefloor – whether it’s the piano house ecstasy of “Daddy,” the dynamic harmonies on “Rain Water Promise,” or “Fields,” which borrows both the relentless drum programming and intensity of Latin freestyle. Lyrically, however, Brown fills up these hedonistic sound frames with social commentary, capitalist critique, and real emotional depth. – Julian Brimmers

How do you write about an Aesop Rock album? From his aughts prime as a Def Jux verbal ruffian to his present-day incarnation—pushing 50, “my hair is gray, my belly’s fat”— he’s constructed his discography as a field of study. There are questions: Is Aes really more interested in the impact of technology on human evolution than he is in his grandma Mary, meeting Mr. T at the Carnegie Deli in the 80s, or pigeons? There are no answers.

Integrated Tech Solutions is not a concept album from the veteran rapper. If you think that sucks, I’d argue that the idea the rapper born Ian Bavitz would make an album about only one thing is far more depressing. Instead, Aesop introduces the titular shadowy corporate entity—something like Tesla by way of Lockheed Martin by way of Aum Shinrikyo—over jazz cup futurist synths, the corporate world salad (“streamlined implementation of attainable solutions”) building to a thematic crescendo: “ITS is not a cult.” But after the uncharacteristically straightforward “Mindful Solutionism”—a PowerPoint tour through the history of technological innovation from the wheel to modern day—Aes settles into his trademark metier: “Ghostface does Buñuel” is surrealist encyclicals interspersed with vivid story.

There’s an oft-cited quote from James Joyce about the famously impenetrable Ulysses: “I’ve put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant.” Maybe the concept album frame is not him throwing us a bone. Maybe it’s misdirection. Maybe he’s just fucking with us. As Stephen Dedalus said, “A man of genius makes no mistakes. His errors are volitional and are the portals of discovery.” Keep those portals coming, Aes. – Jordan Ryan Pedersen

Danny Brown was our adderall admiral, the prince of party drug rap. He lined up coke before the show, then brought out the molly on the way to the after party. He promised impossible highs, but the lows dropped lower than the sunken place in Get Out. His new album, Quaranta, reckons with the come down, the moment when those good times end and all that’s left is an empty bank account, broken relationships, and opportunities squandered. Danny always had the enviable ability to turn his addictions and vices into incredibly engaging rap songs, but on this new album he asks, “At what cost?”

The Detroit born rap icon went from G-Unit castoff to Fool’s Gold alumni until he reached his current mantle as the rap figurehead of the typically IDM-leaning Warp Records. On Quaranta, he traces his path like Hansel, figuring out when and why the games ended in losses and all that accrued goodwill turned into an empty life. Best New Musics don’t pay the bills, after all.

Quaranta, which means 40 in Italian, is less a spiritual sequel to Danny’s breakthrough LP XXX than its counterpoint. XXX was a desperate attempt to cash in on rap promise, and Quaranta is a reflection of the good and bad that comes with relentlessly chasing a dream. On the opening title track, Brown sets the stakes and outlines the emotional thrust of the entire project. It’s a succinct gut punch, a distillation of the euphoric highs and manic lows of the Danny Brown Experience: “This rap shit done saved my life / And f*cked it up at the same time.” – Will Schube

Since arriving in 2017 with her EP debut FRANK, the Dallas-born R&B singer-songwriter Liv.e has experimented every which way with her voice and her musical soundscapes: George Clinton funk harmonies transported to a chant circle and jam sesh (“Come In”); repeated, emotional phrases delivered urgently and never faltering (“thewordspouredoutofmymouthat9PM”); vocal inflections blended so finely into the background as to resemble their own instrument (“Lessons From My Mistakes...but I Lost Your Number”); incantations muffled to the point you attempt to lean in to your headphones, even though you know that won’t uncover anything. Not that the elusiveness is what matters; it’s the urge to find out that counts. If anything, that’s what’s always defined Liv.e: her mastery at grabbing listeners by the ear and tossing them into her tumbling sonic collages of echoing vocals, layers of synths, old-time-soul samples, frantic but rhythmic drum fills. If Girl in the Half Pearl has now become Liv.e’s best-known, most acclaimed work, it’s likely because this album (only her second full-length) contains some of her most compelling artistic expressions to date.

From the distorted screams of “Ghost” and “Clown” to the music-box piano tinkling of “Wild Animals,” the 17 tracks of Girl in the Half Pearl show Liv.e confidently taking on bold stylistic choices, to astounding effect. In “Heart Break Escape,” minor-key synth arpeggios reminiscent of early Odd Future production set the stage for a short story where an anguished, spurned lover tries to rediscover her strength in a bar. For “Our Father,” syncopated organ grooves and drumbeats with a sprinkle of static are the flavor of choice for a soft prayer that swells into religious doubt, with Liv.e’s voice screaming in desperate anguish reminiscent of Kendrick Lamar’s “u.” With “Find Out,” produced by the great MNDSGN, the party siren that introduces Redman and Method Man’s classic “Da Rockwilder” is looped and synced with a pounding kickdrum, evoking a racing heart so familiar to anxious lovers (“I’m dreading thinkin’ ’bout you/ All the voices say it’s dust/ I’m steady losing my cool”). When Liv.e talks her shit and tells the media she’s “peerless,” you gotta admit she has a point. – Nitish Pahwa

Earl Sweatshirt was a folk legend before he could legally drink. Circa 2010, he and his irreverent skater friends overran popular culture. Record labels, magazines, festivals, talk shows, and pop stars would soon jockey to share oxygen with Odd Future and the movement it presaged. Just as phones started ringing, Earl’s mother sent him away to a “therapeutic boarding school” in Samoa to temper his youthful intransigence. The promise he showed on his debut mixtape and his subsequent absence gave him mythic stature.

A decade removed from the initial torrent of blog era hype, Earl Sweatshirt, now a father, raps, “It wasn’t easy, but we grown men.” On VOIR DIRE, produced by The Alchemist, the youthful provocateur rapper from Obama’s first term has long since departed. Earl assumes the burdens and compromises of adulthood without forgetting where he came from.

In an interlude, a voice asks, “by what ill fortune did a prince turn into the reclusive hermit you are now, here, on this desert isle? Was it because you found the world distasteful Or through the perfidy of some enemy?” Earl answers circuitously, enveloping himself in a batch of rough hewn Alchemist beats. Thumbing banknotes, he considers ancestral hurts, his relationship with his hard-nosed mother, and the obligations of fatherhood. Once the misanthrope, Earl swaggers as one of rap’s best writers, showering strippers in foreign currencies. He evinces no regrets, least of all about charting a course underground: “Full-length feature films what we up against. You know the drill, keep it real, they gon’ f*ck with it.” – Evan Nabavian

Drakeo The Ruler and Ralfy The Plug will certainly go down as one of the greatest brother duos in the history of recorded music. Drakeo was the superstar of the two — the unabashed, outspoken leader who originally carved a path out of South Central for the both of them. But Ralfy was there the whole time, always in the cut and ready to follow his older brother’s lead. And it was Ralfy who rose to the occasion of keeping his brother’s name alive after Drakeo was stabbed to death in front of him just over two years ago at a festival in Los Angeles. Since then, he’s picked himself up and stepped on the gas, keeping the truth alive through nearly a dozen solo records, an incredibly underrated posthumous Drakeo release last year and, most importantly, an extra ten songs added to A Cold Day In Hell, the brother’s only full length collaboration.

The tape was first released back in 2021, on the birthday of Ketchy The Great, who had passed away a few months prior, with Drakeo telling The Fader that he was excited for everybody to hear his brother’s skill on the mic. The original is some of both of their best work, with the brother’s easily playing off each other as if they’d been sharing lean and committing robberies together since they were teenagers.

With the deluxe edition, released in September, Ralfy hasn’t merely cobbled together what he could in the face of a desperate situation. He’s managed to take his time and put together what amounts to an entire Drakeo album, complete with all the shit talking flourishes fans have come to expect. Its excellence makes up for the disastrous release of the Drakeo x BluckBucksClan collab, which disappeared off of streaming sites within hours after dropping.

I have to imagine the bulk of the songs on the deluxe were recorded during Drakeo’s legendary run following his release from LA county jail. On “Outdated,” we get classic Drakeo-ism’s like “all my opps get chastised,” and “this Canon on my hip didn’t come from Best Buy.” A majority of the beats were handled by Thank You Fizzle, and fit snugly next to the previous 20 tracks on the original. “Store Runner,” featuring the late Moneysign Suede, and “What Happened To Deebo,” are new Stinc Team classics, showing Drakeos natural tendencies to create new slang and find new ways to embarrass those beneath him. The deluxe edition of A Cold Day In Hell now includes 30 songs and not a single one is skippable.

Ralfy also released a deluxe version of No Bloopers, a total of 35 new songs, some of which featuring unheard Drakeo verses and appearances from 03 Greedo and EBK Yung Joc, among others. He’s easily the most prolific rapper in LA for the second year in a row, releasing more music than just about anyone. He seems thrust forward by an intense need to keep his brother’s name alive. It’s given his life and the lives of everyone around him a deeper meaning and it’s this brotherly love that keeps him moving forward. “Muddy Mosely” see’s Ralfy rapping over a reworked version of Ashanti’s “Foolish,” to great effect. Elsewhere, Ralfy and Greedo reunite for “Real Life Or Fictional,” bringing the best out of eachothers mumbled vocals like they used too six years ago. After everything both Greedo and Ralfy have been through the past five years, it’s a blessing seeing them unite and release the best music of their careers. It’s amazing what can happen when you set your mind on keeping the truth alive. – Donny Morrison

The opening moments of Kelela’s long-awaited sophomore album, Raven, break atmospheric pressure. Her voice on “Washed Away” slowly eclipses the sparse production, as she sings, “and I’m far away,” while growing closer and closer to the listener until we are within the phonemes of her guttural expressions. A statement piece of an intro, Kelela, in her most realized yet still most alien form, has landed.

From there on, Raven evolves into a playground of left-field electronic jams and heartfelt vocal exercises. The album situates itself in the eye of a storm of yearning (“Happy Ending”) before contorting into the trough of wavy and sensual displays of a “submerged sound,” as on “Fooley.” These musical refractions mirror the moody cover of Raven. Everything works in concert, in the service of Black, queer worldbuilding. These complicated displays of hooks and song structures are the foundation of Raven, which is ultimately a love letter to the basis of electronic music as developed by Kelela’s intersecting communities.

Since her 2013 mixtape CUT 4 ME, her 2017 debut album Take Me Apart, the scope of popular music has not quite caught up and cheapened the textures native to Kelela’s sound. The monied and greedy have come close, and of course there are lesser imitators, but it seems like Kelela knows she cannot be commodified as on “Holier” she whispers, “I’d rather be holier” and I read it as a concise and incisive artist statement. In 2013, the Maryland-raised singer was frequently dubbed a dream pop “dynamo.” And while this blurb is not a place to litigate genre, I will say the word choice undersells the meditative intricacies woven into every Kelela release. Raven is sumptuous. The album finds Kelela at an apex point a decade into her recording career. She is unwavering, unmoved by the tides of the industry. She is a “raven reborn.” – Donna-Claire

A global perspective has always been an essential part of Gabe ‘Nandez. The son of U.N. Ambassadors, ‘Nandez spent time growing up between New York, Jerusalem, Haiti, and Tanzania. He learned how to speak English by watching TV shows while attending French-speaking schools. On the NY-based polyglot’s 2023 stylings, he lets his globalist mindset run free. The first album he released this year, Pangea, evokes the prehistoric supercontinent that once united the landmasses of Earth. The second, H.T. III, was composed following a journey through the desert expanses of central Mexico in search of peyote and the otherworldly realms it unlocks.