Photo courtesy of Warner Bros.

Pete Tosiello wants you to know that Scott Caan actually had bars back in the day.

Y2K-era masculinity was weird. Unlike our stoic boomer forebears, who were expected to feel nothing in the shadow of parents who’d survived wars and depressions, the turn-of-the-century male had feelings, he just wasn’t really supposed to talk about them. I’ve often felt that this crisis of articulation—the inability to discern which and how many feelings were okay to communicate—was the reason so many guys my age ended up school shooters and QAnon trolls. We needed to talk about Kevin, we zonked him with Ritalin instead. On the one hand, a lot of troubled young men never learned how to express themselves with words. On the other, a lot of them could, but knew better.

This is one of the fundamental paradoxes of rap music, which reached its cultural diffusion sometime in my early childhood: rappers are the most verbose performers in American arts, and (at least in the late 90s) tended to be the least in touch with their emotions. The finest writers of a generation, poets who captured a revolution in sixteen-bar increments, never offered glimpses beneath the hood; when Nas and Eminem rapped about sex, it made you want to join a monastery. DMX transcended his generation of performers—literally no one was better at talking about his feelings—but he was also one of them. Often times, he conveyed just as much through barks and grunts as he did through words.

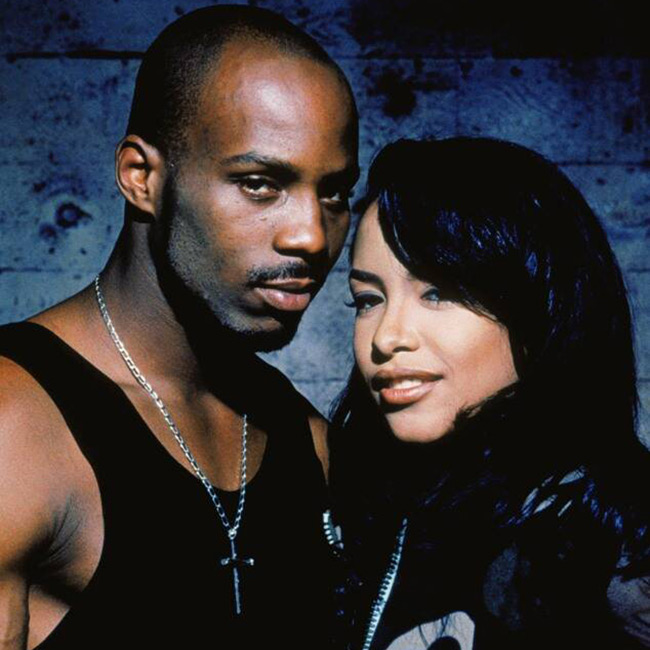

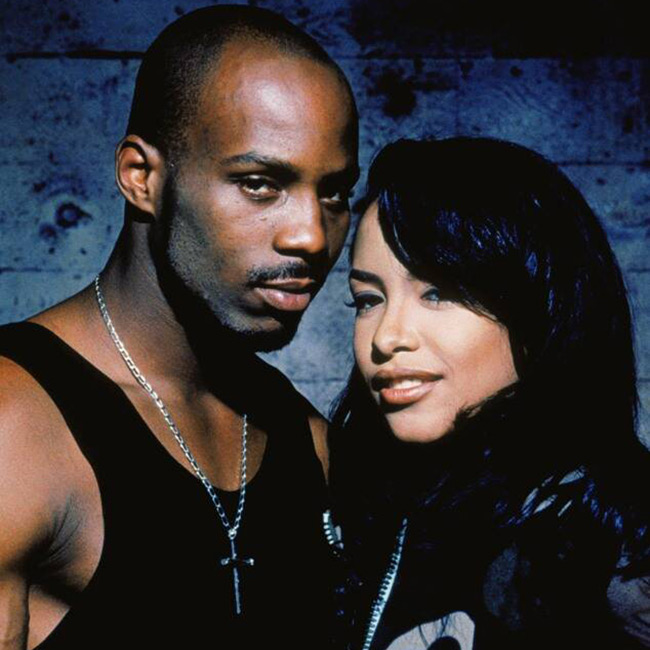

I return to the “Miss You” video, released a few weeks after Aaliyah’s plane went down in the Bahamas. The simple fact of Aaliyah exposed a number of DMX’s peers as pedophiles or just plain creeps, but it’s my favorite image of DMX. He stands before dozens of guys in Avirex jackets, a silent, morose legion of young men shuffling their feet, unable or unwilling to voice their grief. In mourning, DMX is their envoy, chosen because he had enough heart for all of them, an emissary between this world and the next. His job is to acknowledge the suffering while compelling them to fight another day.

I’m curious how history will approach DMX, because one of the you-had-to-be-there elements of his music (and by there I mean virtually anywhere, because his music was and is inescapable) is that his verses don’t look like much when transcribed. They are lists of names and inanimate objects, manifestos about everything and nothing in particular; open up your back, now I can see through your stomach. It was the ceremony of it, the way he always arrived growling, out of breath, drenched in blood. Prayers and hymns don’t look like much when written down either—it’s the act of saying them, and the way you say them, that makes them worthwhile.

The Aaliyah video is mostly really bad—after the intro, it’s just three-and-a-half minutes of lip-syncing BET stars swathed in abominable denim—but DMX’s monologue finds the perfect gravitas for an occasion of senseless, tragic death. Often in these situations folks will deploy the cliche that “There are no words,” and that more or less carries here. He struggles to look directly at the camera and manages the sort of bromides you tend to hear at funerals from people who will do everything in their power to forget them. DMX could toy with you like that: one minute he’d be the most honest, vulnerable man in the world, and then you’d have to remind yourself that he was fucking DMX. He didn’t always capture the weight of the world with his words, but the fact that they were coming out of his mouth, sounding like that, imbued them with a significance that was greater than language. It wasn’t a hood thing, it wasn’t a New York thing. He spoke for all the dogs at a time when most of them were muzzled.