Photo courtesy of NBA Entertainment.

Show your support to POW’s keyboard warriors by subscribing to the Passion of the Weiss Patreon.

Abe Beame runs into the weekend like he’s Jeff Van Gundy in the ’98 Eastern Conference Semifinals.

In 2020, at the height of tensions in the NBA Bubble just outside of Disney World, an alleged dispute erupted in a closed door player meeting between America’s beloved dickhead, Patrick Beverly, and NBA Players Association Executive Director, Michelle A. Roberts. The meeting was held in the wake of the shooting of Jacob Blake, and the Bucks subsequently sitting out their first round playoff game against the Magic, forcing a league wide shutdown. There was talk of potentially canceling the season. Michele Roberts was in the meeting, attempting to explain the financial ramifications of what a walk out would mean, caution which of course was in the player’s interests, but also the league’s.

Pat Bev stood up, and told Roberts he disagreed with her logic. When she tried to speak, he shut her down, saying, “I pay your salary.” We’ve never gotten much clarity on the details surrounding this interaction, or what Pat meant exactly. But it’s a scenario that isn’t new to the relationship between NBA athletes and the person elected to negotiate on their behalf. Roberts followed in the tradition of many NBPA heads, as a non-player, negotiating, compromising, and sacrificing on the behalf of others. The NBA players do indeed pay the salary of the NBA Players Association Director. However, one of the oldest and most maddening paradoxes of the league is, it is not always clear exactly who the NBA Players Association Director works for.

In the NBA there is a game within the game being played between players and owners. It dictates the terms of engagement in the league. It’s a war of attrition between the NBA players and the people who own the companies they work for. The NBPA director is the tip of their spear, the steadied hand that calms the passions of a large and diverse body of workers and unifies them under a banner. That banner is the collective value of their labor, the nobility of their work, and the spirit of fairness that will ultimately reward the players with their fair share of the pie. At least in theory.

The history of the NBPA director position is messier, at times uglier. It begins with Larry Fleisher, a pioneer who remade the league as a place that would no longer function as a basketball sweatshop. But once a seat was finally pulled out at the negotiating table for players, what has followed has at times been scandal, dissension, palace intrigue, loud and angry public arguments, legal maneuvering, hurt feelings and damaged reputations. Depending on what level nerd you’ve achieved, it can be as fascinating as the product on court, which is changed with each Collective Bargaining Agreement.

In some ways, the strength of the NBPA, the dedication of its actors, be it stars or negotiators, the gains the players make or the losses they suffer, can be seen as an echo of the health of the labor struggle, or our legal system, or the political mood towards labor in this country. We ascend under happy warriors like Jimmy Carter, we see our gains pulled back under the yoke of ruthless nihilist corporate shills like Reagan and Clinton.

Following the Big Bang of the Robertson Decision in 1976, the league was determined to scale back on players rights and earning potential as the planet cooled and life on the soft earth began to organize itself. The negotiations became cyclical. You could write a script. The league manufactures claims of poverty, and demands change to save the game. The players attempt to hang on to what they’ve earned through litigation, arbitration, and negotiation. Things become increasingly tense and dire, and eventually, the players, and their representation, fold.

This is an exercise in evaluating NBPA directors, how well they worked with the unions they inherited, what they won for their constituencies, how good they were at doing the slow and sticky work of labor dispute. But the arc of sports labor is long and bends towards ownership. LeBron James is seen as a marvel of professional accomplishment and medical science in his endurance and longevity. He’s been in the league for an incredible 17 years. He currently plays for the Lakers, owned by the Buss family for the last 42 years, five years longer than LeBron has been alive.

That is to say, it’s a hard job. There are only 30 NBA teams and over 400 NBA players. The owners are older, richer, and increasingly more sophisticated than the bad old days when Larry Fleisher got to spar with fucking morons like Ted Stepien. But what we’ve seen since 1995 is an unprecedented series of losses, with some of the CBAs contested under not unreasonable allegations of colluding with ownership against players’ interest.

It’s easy to dismiss this entire discussion. When I was a kid, in the year he led the Knicks to the NBA Finals, Patrick Ewing made $4,486,700, or $7,815,255 in today’s dollars. Today, that salary would place him below Seth Curry as the 165th highest paid player in the league. And that stat says nothing for the league in the 50s and 60s, when guys like Oscar Robertson and Wilt Chamberlain were considered lucky for having income supplanting, “plush” offseason gigs like teaching my dad how to play basketball at Kutschers in upstate New York. Because of roster size, on average, the NBA currently boasts the highest paid professional athletes. So should we, can we really critique the work of the negotiators who enabled the players to reap these incredible rewards?

What we’ve seen over the course of the last 40 years is that capitalism is a zero sum game. It’s hard to imagine a time when the players won’t be comfortable, to say the least. But it leaves open the question of what they deserve, what their labor is worth to the organizations that profit off of them. Just as salaries have skyrocketed, so to has league revenue, and team values, at a rate that far outstrips what the player’s are making. Seth Curry makes $7,815,255 this year, the Golden State Warriors are currently valued at 4.7 billion. NBA players are one of the few super wealthy groups who the graduated income tax still applies to. As their wealth has increased, the percentage they see garnished by their bosses has risen. And appropriately, constitutes a transfer of wealth benefitting one of the few groups in America that has much more money than them.

How much would LeBron James’ services be worth on a truly open market? It’s a question many of these bloodless VC types that have slowly absorbed the league never had to ask when they were making their fortunes as analysts, or lawyers, or whatever. They didn’t enter a system that forced their employment at the shittiest firm in their industry to promote parity. But this is the system that Fleisher ultimately created, and now we all have to live with.

It’s easy for us, mired in our working and middle class existences, to scoff at the idea of millionaires and billionaires playing tug of war for percentage points. It’s harder to imagine being one of the few best and most talented athletes on the planet, having a cap placed on our value, having our careers and finances dictated by a cabal that runs a sanctioned monopoly in our field, and just kind of sitback and watch as your services are continually devalued, though you’re making more and more for the capitalists who do little but profit off your labor.

So consider this a referendum. Our way of grabbing Michelle Roberts by the shoulders, and those that will follow her, and demanding they do better. Of telling the players to learn from the mistakes of unions past, to unify, stand together, and demand more, not just for themselves, but for their kids, for the future of their sport. In 2013, following another shitty deal in which the owners placed their hands directly in the players’ pockets, agent Arn Tellen wrote of 17 year NBPA Executive Director Billy Hunter: “(He) works for you, even though he clearly doesn’t realize it.” Let’s change that.

6. Billy Hunter (1996-2013)

Photo courtesy of Associated Press.

Greatest Triumph: Briefly nudging the BRI split back up to 57%.

Biggest Mistake: Oh buddy…

George William Hunter earns the bottom spot on this list because he was uniquely untalented at his job. He was a fed attorney and prosecutor who had gone after the Black Panthers, among others. The league hated him, the union hated him, and the media/public hated him. To accomplish this trifecta is its own kind of achievement. He came in as a rolled shirt sleeves, bare knuckle brawler fighting for the NBA’s working class, and quickly got washed by the owners, losing each negotiation and offering up givebacks on subsequent CBAs as he grifted away the union’s trust and got fat off their dues using his own children as a fence.

Hunter’s reign in many ways echoes the tenor of the Clinton administration. It was a charade that hid in plain sight as a liberal project, with Hunter assuming the role of the people’s champion, as he grabbed his ankles for the super rich and boosted pork out the back door. During his 17 year tenure, the second longest in NBPA history, Hunter oversaw three Collective Bargaining Agreements which resulted in two lockouts.

It didn’t have to be this way. During the period Hunter ran the NBPA, from 1996-2013, awareness of the labor disputes between the players and ownership rose. After generations of being dismissed as overpaid and ungrateful (Black) babies complaining about their “job” playing a children’s game, the players finally were acknowledged as having a case in the court of public opinion, as well as the media. Fans became better educated with the rise of the internet, and sentiment shifted against ownership.

For the first time, the fight between Black millionaire players fighting with their white billionaire owners for a fair share of the money they made for them was seen as a just and fair fight. These shifting conditions should have worked in the players’ favor under Hunter’s stewardship. Instead, with each one of Hunter’s CBAs the player’s lost either rights, money, or equity, and in some instances, all three.

1999:

Just four years into Simon Gourdaine’s 1995 shanda staving off a work stoppage, the owners voted to reopen the CBA that negotiation produced. The league had gotten the rookie wage scale it wanted in ’95, but a loophole was left open. Larry Fleisher, in his landmark agreement with the league in 1983 that first established the salary cap, had woven three exceptions, named after specific players, into its fabric so as not to overly restrict the salaries of star players and the cap flexibility of teams. One of these was known as The Ralph Sampson Problem, which was what to do if a team was capped out and had to sign a rookie. Part of the solution involved an option for rookies to opt out in their second year and renegotiate, which created a new problem, leading to even richer and longer deals for guys like Kevin Garnett.

It was a poison pill the league could no longer swallow. By the late 90s, under the soft cap, thanks to a few monster deals, player salaries had reached 57% of league revenue, a number unseen since the year before the cap. Owners wanted a hard cap, elimination of Bird Rights, a 5-year restricted rookie wage scale, and a proposal that no player’s salary could exceed a third of the cap.

Something that will begin to emerge during this discussion is how the players, and their material conditions began to impact these negotiations. Whereas in the past, the players union had been a unified front with an eye not just on the present, but the future, what began to emerge, beginning with the NBA’s first real work stoppage, was a short-sighted greed. When the paychecks stopped flowing, guys like Kenny Anderson became squeaky wheels, the owner’s saw this weakness, and pounced on it.

You can blame the players, but the union head’s job isn’t just to negotiate, it’s to be intimately familiar with their union, keep its members in line, and whip votes when necessary. One of Hunter’s many dumb moves was a refusal to really engage with agents, to not make them partners in negotiations, which created a powerful and influential fractured group of discontents and helped foment unrest and dissension amongst his constituents.

Hunter also failed strategically during this negotiation. Time is an urgent factor in all labor negotiations, and it always favors management. Hunter was callous with his, not particularly pressed to get in a room with David Stern as the clock ran out on the CBA, then the offseason, then the first check date. To be able to attack the league by suing for antitrust, the NBPA needs to decertify, a gambit used since the beginning of the union itself in these negotiations. It’s a long process which can be painful for the players, but has worked as a reliable threat over the years.

Instead of going to it, Hunter attempted to go to arbitration over whether or not a work stoppage meant the players’ guaranteed contracts needed to be paid. It was an ambiguous legal question that had been hanging over these negotiations for years, more attractive as a threat. Hunter submitted to an arbitrator rather than the courts, which would have taken significantly longer but might have had a better chance resulting in a favorable decision. Instead, the arbitrator decided that the right to withhold pay in a lockout was consistent with labor law. When that happened, it was basically over.

After the 1999 lockout, the owners secured a luxury tax, an escrow tax, and max salaries. Basically all the players received were minimum salaries, cap exemptions, and benefit extensions mainly protecting the NBA middle class, as well as retention of several things the players already had that the owners wanted to take. In other words, they were thoroughly rolled.

There was no fixed basketball related income split for the first three years of the seven year agreement, but in years four through six, the number jumped to 55%, and in year seven it would be 57%. The owners essentially started from a place of wildly irrational and unreasonable, attempted to starve out the players for a few months to test their mettle, then finally settled for a simple W rather than a blowout.

2005:

This was the only Hunter negotiation that didn’t end in lockout, but it was another win for the league. As we’ll discuss in depth in a moment, they shortened contract lengths, raised the minimum age for draft entry to 19, and limited annual raises. What the players “got” was once again, staving off the really crazy demands the owners brought to the table, as the sand of equity incrementally continued to run between their fingers.

2011:

When we get to several other NBPA directors shortly, keep in mind (paraphrasing an ESPN report from 2009) this was Hunter’s list of demands going into the 2011 CBA negotiations: Repealing the age limit, reducing the amount of player salaries held in escrow, loosening restricted free agency, and changing the league’s disciplinary system. Folks, when you suffer from this sort of poverty of imagination, you’ve already lost.

After 20 years of chipping away at the structural player advantages the CBA allowed for, in 2011 there was little left for the union and owners to debate besides the size of the cut. You’ll never believe this, but the owners claimed under the then current 57% split, 22 out of 30 teams were losing money and the league, despite TV deals getting increasingly gaudy and the values of teams skyrocketing, they were losing 300 million dollars a year (Forbes disproved this with a fascinating deep dive, showing by their accounting the league actually made 183 million this season, concentrated in its larger markets).

The common sense answer would seem to be demanding the teams increase their revenue sharing percentages, rather than once again sticking their hands in the players pocket to solve business and league problems. But incredibly, the union came to the table willing to make concessions on Basketball Related Income. The question was just how much they’d “have” to give up.

The owners came in with a wildly aggressive proposal, reducing player salaries by 40% and setting a hard cap at 45 million dollars. The players countered with reducing the BRI split to 54%, and a five year salary reduction of about half a billion dollars, as opposed to the two billion the owners were demanding. The players had a breaking point of 53%, a historically significant number as it was the BRI split agreed upon in 1983, the year of the birth of the salary cap itself, and a level the split hadn’t dropped below since. The owners wanted 47%, which seems arbitrary but probably has some connection to demonic numerology and child sacrifice that meant a great deal to Donald Sterling, James Dolan, and Dan Gilbert.

After missing their first paycheck in November, the players voted once again to decertify so they could sue for antitrust violations. Within 15 hours of doing so, a deal was struck. The cap remained flexible, but BRI dropped to 51%. Teams got an amnesty provision to cut CHAUNCEY BILLUPS?? a single dumb contract from their books. The players also got the Derrick Rose Rule, which is dictated by All NBA selection, allows for a 30% bump with the expiration of a player’s rookie contract, and applies to maybe 2-3 elite players every few years. These types of special wonky exceptions will reflect the coming emphasis on narrow changes for superstars in the coming years of negotiations.

There’s some idiotic defending of the 2011 deal done with hindsite. I guess the argument is that because the league has exploded since then, post the last ESPN/TNT deal, the players should be grateful the deal was done? If they hadn’t capitulated and stayed locked out then the league wouldn’t exist? Or something? This side willfully ignores that had the union and its leader shown more spine, even more of that tremendous windfall could belong to the players.

Fallout:

Several key members of the union weren’t happy after the 2011 lockout. They had lost money and the negotiation. There was also the allegation that Hunter was guilty of the soon to be discussed Simon Gourdine’s move in 1995: Meeting with Stern without player representation. They opened an investigation into what was becoming Hunter’s increasingly brazen and shady business practices.

The extremely damaging resulting report concluded Hunter wasn’t caught directly embezzling, but unquestionably used the union to enrich himself and his family. His daughter in law Megan Inaba, for instance, was the NBPA’s “Director of Special Events and Sponsorships”, a job which involved running the union’s social media accounts and planning All Star and Summer events. Here’s some hidden cam footage of Inaba on the job:

Hunter’s daughter, daughter in law and son all received union funds in one form or another. Hunter’s son ran a bank and had some role in this investment firm, Prim Capital. I’ve read multiple reports about the deals Hunter set up with Prim, and I still don’t have a clue what it was exactly Prim was supposed to actually be doing for the union. During the 2013 All-Star break, team reps gathered to vote on Hunter’s future and unanimously elected to fire him. After his dismissal, Hunter dragged out legal proceedings against the NBPA for years in an attempt to retain lost salary and severance. It was a fitting end for a self serving piece of shit who committed sins of incompetence, potential collusion, and theft against the constituency he was supposed to serve.

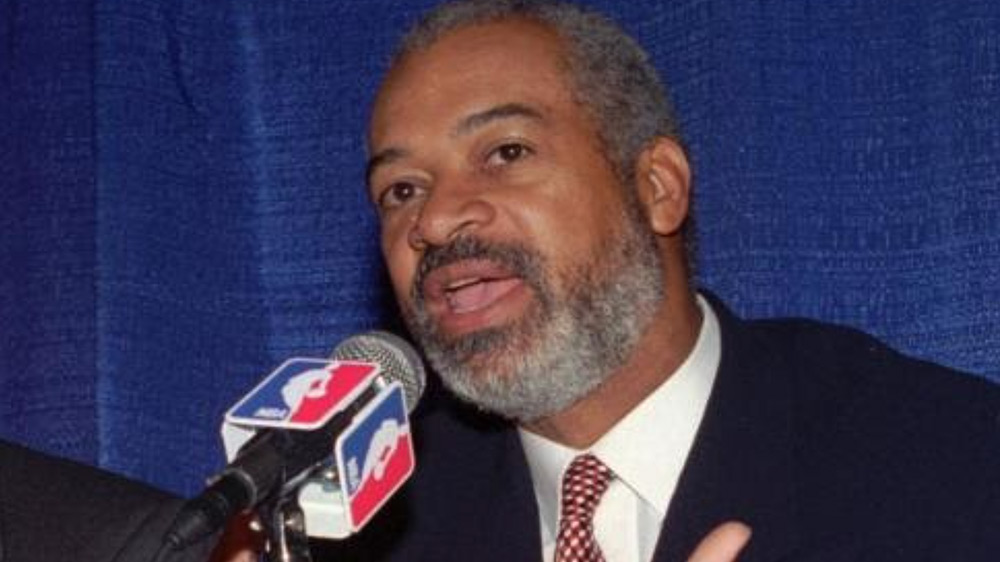

5. Simon Gourdine (1995-1996)

Photo courtesy of NBA Entertainment.

Greatest Triumph: Avoiding a work stoppage in 1995.

Biggest Mistake: MAKING AN AGREEMENT WITH THE LEAGUE WITHOUT FIRST CONFERRING WITH TEAM REPS.

Simon Gourdine was an industry plant and obvious opp. He was the NBA deputy commissioner from 1974-1981. He also served as the fucking deputy police commissioner in New York City under Ed Koch. He broke into the league as legal counsel, and while serving as deputy helped the league negotiate CBAs with the NBPA in 1976 and 1979. He was angling for the job of commissioner following Larry O’Brien. When he was passed over for David Stern, he eventually quit. Somehow, with former NBPA director Charles Grantham “resigning” so he wouldn’t force a work stoppage in 1995, the union believed Gourdine could represent the players with no conflict of interest, and installed him as Grantham’s successor.

On the table for the NBPA was a larger share of licensing, which had exploded for the NBA and was outside the purview of the salary cap, and preserving Bird Rights. But the owners were able to enact a rookie wage scale in the wake of Anfernee Hardaway and Chris Webber’s massive rookie contracts, and eliminated balloon payments, fucking over players like Mitch Richmond. It was two key items on a wishlist intended to drive costs down the owners were able to strike through, the players effectively ate their young to get a piece of the merchandising pie they should’ve already had.

Cap loopholes like the Chris Dudley deal were closed. An initial deal over a luxury tax was stricken from the agreement due to player unrest, the league finding a sticking point they were comfortable removing to appease the unhappy contingent. The owners celebrated the agreement as a win. Why shouldn’t they? There would be many more CBA negotiations to continue to extract demands like a luxury tax in their futures, as their pie, and the value of their investment, grew exponentially.

In some ways, Gourdine was a manifestation of what seemed to be the majority will of the union at the time. Though they couldn’t come out and admit it, they were happy with their compensation at the end of the day, and didn’t mind putting a cap on rookies, forever altering the power structure in the NBA and creating a seniority system. They saw the rookie salaries ballooning as teams were forced to dedicate more and more to potential assets rather than realized, if somewhat unexceptional vets, and pushed back, essentially siding with their owners. (A brutally honest David Falk: “Renegotiating the rookie wages was a cosmetic victory and neither side understood the future result of their actions.”)

For the first time, the players lost on the key points the owners brought to the negotiation. Gourdine was embroiled in controversy, making what was perceived as a closed door deal with David Stern without league members present. A last second rogue attempt to upend the deal and decertify the union by NBA stars like Michael Jordan and Patrick Ewing was voted down.

(I mean listen to this fucking guy. You want to talk about double agents? He’s practically reading the script Stern wrote to defend the deal. In discussing the decertification vote by a rogue band of players that constituted a sizable minority, he keeps saying, “We believe we are going to win this vote.” WHO THE FUCK IS WE?)

But bad blood and dissatisfaction with the deal lingered once the union went back to work. Gourdine was initially awarded a two year contract by the NBPA executive board for his “efforts” securing the agreement. It was overturned by a player vote and Gourdine never worked in the league again. But not before he secured a $900,000 severance package.

It was as if the players understood they had a small mountain of rotting debris in their front yard that needed hauling so they could resume their comfortable lives, found a service the city recommended as the quickest and cheapest, if not best option to to solve the problem, but once the trash was gone, realized a sycophant scammer for what he was. So after an extensive headhunt, they went out and hired Billy Hunter.

After Gourdine’s bargain, David Stern gave a statement. 26 years later you can still read the smug gloat oozing out of his words: “You won’t see any more Chris Dudley or Danny Manning deals. The high jinks that our fans know are just that. Aside from the fact there won’t be $15 million balloon payments, you’re going to see some spirited activity in the signing of free agents with higher salary-cap numbers. And you won’t see crazy rookie contracts. Owners will still have the opportunity to spend their money crazily, but they’ll do it on proven veterans.”

You can imagine now, that the NBA’s own Napoleon was addressing generations of players to come. What they could expect, and what they had to look forward to. But more immediately, he seemed to be speaking directly to his vanquished foe, Charles Grantham, and his dream of a more equitable league. Simon Gourdine helped kill it.

4. Michele Roberts (2014-Present)

Photo courtesy of NBA Entertainment.

Greatest Triumph: Enjoying the fortune of getting the job at the moment the league signed its historic TV deal.

Biggest Mistake: The Supermax?

As a B-/C+ student of history, I’ve come to the conclusion that times of prosperity make for shitty liberals. In Michelle Roberts, and the present state of the NBPA, enjoying unprecedented wealth and success, we see that concept in its full manifestation. Roberts, and the NBPA in general when it comes to labor negotiations, has mirrored the direction of the country, catering to the super wealthy and working deals to increase that gap as they pay lip service to humanist collectivism.

That lip service typifies the hollow-and-soulless-virtue-signaling/postable-rhetoric-while- practicing-dog-shit-neo-lib-politics-of-the-ongoing-Obama-era-Democratic-Party. Consider NBPA president Chris Paul, who is doing loud and admirable work campaigning for HBCUs, while also using valuable negotiating capital to pass a rule so specifically tailored for him they named it the Chris Paul Rule (Also known as the “Over 38 Rule”).

So you know, fighting for Historically Black Colleges, and at the same time ensuring those young Black players who enter the league from those colleges, with the exception of a handful every generation, won’t have it as good as he did. As Americans have been doing since the Reagan administration, the NBPA is, perhaps semi-unwittingly, in the process of gently shutting all the doors and closing all the windows for the generations of players who will follow them by focusing on their personal wealth and short term goals.

Roberts has been the beneficiary of the 24 billion dollar television deal with ESPN and Turner Sports that tripled television revenue and changed the entire outlook of the league in terms of cap and team evaluations (As of 2015, 13 NBA teams were deemed worth more than one billion dollars). With the stakes raised to inconceivable levels, with no real ceiling in sight on growth (will be interesting to see what this next broadcast deal in the shadow of streaming will net them) neither the NBPA nor the league wanted to fuck up the good thing they had going.

So Adam Silver’s first CBA negotiation in 2015 was probably the most pleasant and congenial the league has ever seen. Probably the most important piece is the BRI stayed the same. Still, the provisions the NBPA fought for and secured are telling. And it’s no coincidence. Silver is by far the most transparent, player friendly commissioner, perhaps in any major professional American sport ever. Certainly a far cry from the bare knuckle dictator that preceded him.

David Falk once said, “Fans don’t come to see the 13th guy on the team or even the ninth. This is a star driven league”. Falk isn’t exactly wrong, but this weighting of the star’s interests over those of his teammates exposes a profound misunderstanding of team dynamics, and the hard work the ninth and even thirteenth players do that allows that star to shine. Should stars be paid more? Yes, of course. The problems arise when that earned income for a few comes at the expense of the many in the market.

It begins with the decision not to smooth the cap over the largesse that came into the league via the TV windfall. In theory, Roberts is right. A union should never limit the potential earning power of its players. But in practice, with help from idiocy, and with a modicum of foresight, Roberts and the NBPA should’ve realized that artificially spreading the cap over two seasons would’ve ultimately been net beneficial to more of the union, rather than create one profoundly dumb offseason of wildly overpaid players.

What is interesting about the last CBA is it signals a partnership of league superstars with ownership. Much was done for the NBA’s working class, including better health care, the introduction of two way contracts, and roster expansion. But you could look at these improvements as a pittance, inflation, or the cost of doing business. The players didn’t push for much, with the increased revenue it was more maintaining a system suddenly working for everyone.

The supermax was an attempt by the league to limit player movement, but has really served to concentrate the cap in the hands of a small group of the super rich. If you want proof, the average NBA salary has grown at a rate disproportionate to the median. The elegant solution would’ve been preventing supermax deals from counting against the cap. Of course, without due pressure, the league would never agree to that. And the union hasn’t fought particularly hard for it. Each supermax can account for up to 35% of the cap. Six players currently hold them.

While aspects like raised minimums, and particularly two way contracts aid the proles of the industry, the league also raised the luxury tax apron, percentages on raises went up. These changes do help a very small collection of players at the top of the league, but they’re also benefiting owners, who are doing everything they can to attempt to curtail player movement.

The supermax has the potential to turn relationships fans should have with stars entering their late primes adversarial. The fan has to rationalize their legends kneecapping their franchises. They unfairly expect players to take pay cuts in the interest of winning. This is an unreasonable expectation that the players shouldn’t have to live up to.

At a time when the players were given the friendliest environment for negotiation they’d ever seen, the paltry number of improvements they won most significantly affected the 1%. Sounds like the perfect epitaph for Roberts, a shill for the union’s 1%.

3. Alex English (1996, Interim)

Photo courtesy of NBA Entertainment.

Greatest Triumph: Extracting additional TV profits for the salary cap from the 1996 Lockout.

Biggest Mistake: Injuring his thumb in Game 4 of the 1985 Western Conference Finals. The Nuggets lost to the Lakers in 5.

After a legendary playing career, former Nuggets star Alex English got involved with the players association and was essentially a seat warmer who bridged the gap between Gourdain’s sudden ouster and Billy Hunter’s hiring. He was involved in one of the most bizarre lockouts in NBA history, coming right on the heels of the 1995 CBA, there was a lockout of several hours that occurred between 6 AM on June 9th, 1995, and 11 AM.

The conflict was over how to allocate $50 million in television related profit sharing. The union demanded either all of it, or $31 million, depending on who you believe, and the owners wanted a 50/50 split. In the end, both sides agreed to $14 million per year going towards the cap in the last four years of the CBA. So the players ended up with more than the $50 million they demanded, just not up front. An actual decent compromise if I’m understanding everything correctly.

And just that is enough to land at three on this list.

2. Larry Fleisher (1970-1988)

Photo courtesy of NBA Entertainment.

Greatest Triumph: The Salary Cap.

Biggest Mistake: The Salary Cap.

When we discuss the NBPA Director, or even the NBPA, the conversation, by necessity, will be dominated by Fleisher. He’s Adam, Abraham, and Moses to league labor. Fleisher was a Bronx kid with a wild resume before he got involved with the NBA Players Association that Bob Cousy founded in 1954. As a young man, he wrote what became an influential paper for the Army regarding maximizing efficiency, he was a CPA and a tax lawyer, he owned multiple Wendy’s franchises with John Havilcheck. He worked for the NBPA starting in 1961, at new player president Tommy Heinson’s behest, through the 80s for free because there was no money in it (he made it back as a powerful and influential agent, representing his first client, Bill Bradley, as well as Earl Monroe, Paul Silas, Havlicek, and Lenny Wilkens, among others). He went on to become the longest tenured union director in sports history.

Fleischer’s first issue was a humble request for player pensions. At the time, the owners ruled over the league with all the leverage. They wouldn’t even acknowledge Fleisher as a representative of the union. He would find ways around this intransigence, using the NBA All-Star game as an annual pressure point, getting the owners to the table to negotiate NBPA demands with the game (a national television showcase at a time the league had to fight for that level of exposure) as the carrot, and a wild cat strike as the stick. He also lived to sue, if for no other reason to see what he could finagle in court. It was an era when the American legal system, perhaps for the last time, still had an interest in protecting its workers.

Things changed for the players beginning in 1970 with the history altering Robertson v. National Basketball Association, an antitrust lawsuit that sued the NBA for an unconstitutional merger between the league and the ABA. The lawsuit was a broadside against the merger, the options clause (which prevented player movement), and the NBA Draft. The case ended with The Burger Court’s decision six years later, finding for the players (A case it would be incredibly difficult to even imagine the anti-labor Roberts Court hearing today, unless it was to create monstrous precedence getting out of the way of “business” and “capital”).

As free agency began in earnest in the NBA, the players enjoyed a brief, glorious period post Robertson Decision of having ownership’s balls in a tightening vice. Salaries jumped from a median of $35,000 in 1970 to $100,000 in 1976. In 1981, the player’s owned their all-time highest share of total team revenues with 63.9% in salary (The next year it would be 57%, and the final cap agreement would settle at 53%). In that offseason, Houston Rockets star center Moses Malone would be signed by the new, free spending 76ers owner Harold Katz for a record contract. He’d respond by earning his money, swinging the league and bringing a title to Philly, winning MVP and Finals MVP in a sweep of the Showtime Lakers. It was a vision of the NBA Larry Fleisher had dreamed of. But that season, he decided to assist David Stern and Larry O’Brien in a treasonous, or visionary (or both), remaking of the league.

Fleisher’s legacy is ultimately the salary cap, the most consequential mutual agreement, perhaps in the history of American professional sports labor. So let’s hash out its merits here, once and for all, in an effort to place Fleisher in the pantheon where he belongs. To adequately evaluate the circumstances Fleisher had to navigate, you have to understand the context.

The NBA in the 70s was a chaotic, damaged asset. The league was at the mercy of a deeply racist country (Or, you know, more so) that preferred baseball, football, and hockey. They were contending with a dumbass white conservative public that reactively resented and was hostile towards any labor demands made by a 75% Black players association that had the gaul to ask for more when they made six figures playing a game. The NBA was also locked in a toxic marriage with CBS, who neither appreciated their product or worked to expand their appeal in any meaningful or thoughtful way.

To Donald Sterling’s long and ignominious list of sins over the years, you can partially add the salary cap. Sterling had just become an owner and immediate agent of chaos in the league. He set out to break an agreement and move his Clippers from San Diego to LA without league sanction, and he was already stiffing the league, employees and players on agreed upon dues and compensation. Sterling was the kind of owner the NBPA was afraid of, indicative of a class of spendthrift, unprofessional rich morons who were still able to just barely afford NBA teams in the late 70s and early 80s, and immediately went about the work of mismanaging them. Fleisher believed, correctly, a league mandated set of standards and practices were required to protect players from bad faith rich assholes. The cap did that.

This is the atmosphere in which Fleisher agreed to what might have been the first salary cap in professional sports. The thing that Fleisher’s critics (myself included) take issue with is why? The cap was far from an inevitable conclusion. It places an artificial ceiling on player earnings, limited player movement, and post the Robertson Decision, constituted a giveback to the owners. In fact, it violated the Robertson Decision, and was subject to a court approval, in spite of both sides’ willingness to enact it. That’s what a reach it was. It literally broke the tenets of a labor deal won by the NBPA seven years earlier.

The salary cap constituted a grand, Faustian bargain: in return for placing a limit on player salaries, the players essentially became partners with their league owners, taking a share in the total revenue (including coveted television and cable money) and gambling by tying their fates to the success or failure of the league. It can also be seen as a kind of victory of negotiating by the owners, who initially came to the table with predatory and ghoulish short sighted schemes to save money such as dropping rosters from 12-10 players, making the teams fly coach, and warning of a retraction of multiple teams allegedly hemorrhaging money. Coming to what was perceived as a “middle” where the two sides ended, was perhaps a partial gambit to avoid these draconian (albeit far fetched) measures the owners threatened to unilaterally employ in the absence of a CBA agreement.

The spirit of the agreement was in favor of rising tides and lifting all boats, a solution that would hamper the 76ers as well as future deep pocketed teams willing to outspend its small market competitors for talent, but would also force the small market Indiana Pacers and Washington Bullets to raise their salary minimums significantly. There were no level salaries at the time. Like baseball, small market basketball teams with financially limited owners would be competing against big market teams that could swipe their players easily in an open market. With the cap, parody was baked into the league’s structure, for the first time.

This is how the cap boosted the market for end of the bench guys and role players, the league’s lower middle and working classes, providing them a commensurate league wage where there had been none. It created competition, both for the players’ services and amongst the teams. It was an egalitarian sacrifice the royalty of the union made for the majority of its members. And this was key, because in the NBA, the union is only as strong as the support given by its biggest stars, a support that hasn’t always been there depending on the star in question. In 83, it forced something closer to revenue distribution and a tightening of the wealth gap, not just between teams, but players, who suddenly had a larger pie to divvy.

Because the cap didn’t just standardize salaries, it organized the league and installed standards and practices. It was an inflection point that led to the NBA as a whole maturing and getting its shit together. The possibility of a salary cap enticed the league to open its books, after years of opaque reluctance to show the NBPA that there actually were teams struggling to remain solvent in a mismanaged and poorly represented league, which became standard practice going forward. The players helped save the NBA from itself. With salary caps and the demand of a salary floor came revenue sharing, a smoothing of league inequalities.

It also created stability for prospective buyers. An aspiring owner wouldn’t have to worry as much about the whims of an unstable, open market. They could reasonably project their overhead years into the future, immediately adding to the value of an NBA franchise as an investment. It succeeded in chasing out SOME of the league’s bozo owners and attracted a new generation of more serious, sophisticated ownership.

And so, the NBA players took the longview and saved the league from an existential crisis. It can be viewed in hindsight as a jobs preservation act. But it would also be valid to question whether or not it was the players’ role to perform this act on the owner’s behalf. The players’ job is to win games. The owners’ job is regulation, promoting their business and their league. In the cap, Fleisher did something that may have preserved the league long enough for it to achieve a foothold in the American consciousness and thrive, but what if it had gotten there anyways? What did the players’ give up with the limit the regulations placed on their free market?

The salary cap was envisioned by Fleisher as life support, a temporary measure allowing the league to get its financials in order and grow up. We’re decades past the point where franchises need to fear for the financial life of the league. And yet the cap remains, it proved to be a rubbed lamp, a squeezed tube of toothpaste, etc. What we’ve seen is this bargain has been weaponized by the owners as the league flourished. Now it serves as an artificial and arbitrary ceiling that gets lowered with each passing CBA as the profits, popularity and values of the teams rise with each season. The cap was supposed to be a temporary measure to save the league. Now it’s a cudgel.

It isn’t as if no one saw this coming or thought the cap might be a bum deal that would come back to bite the players in the ass. New York Times journalist Ira Berkow said at the time, “A salary cap is anathema to the free-enterprise system and smacks of an antitrust violation. The owners are capable of getting out of their own muddy mess-if it is in fact a mess-by themselves.”

Fleisher would likely tell you he was doing his best with the circumstances in front of him. He took a futurist view of where the league was going and how to get it there, ultimately to the benefit of the players, but it’s worth asking if the cap ultimately was a net positive for his constituency. If the cap was meant to be a temporary measure, protections should’ve been built into the CBA, and Fleisher opened the door for its oppressive, permanent presence in the NBA. I understand the realities of that moment and why Fleischer did what he did, how no one on Earth could’ve really foreseen where the NBA would end up in its earnings and its place American life, but a question that continues to haunt me is in an actual free and open market, how much would LeBron James actually be worth? 10 times the nearly 40 million he’ll make this year? A significant share of equity in a team? We’ll never know.

As a final black mark, after coming out against drug testing during CBA negotiations in 83, saying the union was against it, and quoting Tom Landry: “We have not yet reached a police state in this country.” Fleisher made an about face in September of that same year. The announced drug testing agreement was harsh. Players were subject to random testing and a three strike rule. Stern’s comments in the wake of the deal had the hawkish, conservative, racist bent that would flavor the rhetoric of the Reagans and Bidens in Washington for another decade plus. It was as much, if not more of an appeasing of the media driven narrative of the league as a harem of Black drug abusing athletes than it was actual concern for its players.

In 1988, Fleisher fought his final battle with the league over a CBA. He was going whale hunting once again, with the elimination of the draft, completely unrestricted free agency, and the salary cap in his sights. For the final time, the league negotiated off its back foot, desperate not to drag the matter into courts. After a standoff, Fleisher won limiting the draft to two rounds (down from seven), unrestricted free agency for veterans, and guaranteed increases to the salary cap, nearly doubling it, along with minimum player salaries.

Fleisher retired from the union following the settlement. He’d devoted most of his professional life to the fight for players rights, and was looking forward to his back nine. He’d be gone the next year, dead from a heart attack during a game of squash at the New York Athletic Club. He was 59 years old.

Perhaps Fleisher’s greatest asset and most powerful weapon in negotiating was his ability to keep his constituents in line. Under Fleisher, the players union was a unified front in a way we wouldn’t see again. This wasn’t just a gig for Fleisher. He knew the public would never come to see his side, but he knew that players deserved rights and a voice, and he never gave a fuck about winning popular opinion. He soldiered through decades of bullshit and fought for what he perceived as just. He was a true believer. But this was perhaps his downfall. History will decide if he ultimately betrayed the interest of his clients, in deference to what he perceived as necessary action to save the league he loved.

1. Charles Grantham (1988-1995)

Photo courtesy of NBA Entertainment.

Greatest Triumph: The Early 90s Hidden Team Revenue Decision.

Biggest Mistake: “Buck Williams.”

Charles Grantham began as an assistant to Fleisher. It’s possible that no one anticipated the future of the NBA and the demands it would make on its players like Grantham did. His agenda was radical and an attempt to make good on Fleisher’s vision for the future of the league as well as build out the players association, transforming it from a negotiating body to a full service organization that existed to serve, educate and protect the players.

Grantham’s goals extended the spirit of the Robertson Decision. He wanted unlimited free agency, abolishing the NBA Draft, and getting rid of the salary cap as constituted. As Exec, Gratham sued the league over misreported income by the teams. Like his predecessor, he spoiled for a fight and was ready to take the league to court when necessary.

From the beginning of NBA labor negotiations, the owners have been, if not masters, then feeble jackasses at talking out of both sides of their mouths. On one hand they promote the league and its limitless potential to media and prospective investors alike, then turn around and claim poverty and impending doom to their employees at the negotiating table. It’s also pulling fucking teeth getting financials off of them, and even when they do, it’s reasonable to assume they’re heavily cooked.

In 1991, thanks to a lawsuit between the Bulls and the league that resulted in evidence of discrepancies between what the Bulls actually brought in and what they had reported to the players, Grantham had hard evidence of this book cooking, and the NBPA brought a complaint to the special master assigned to adjudicate league disputes. The complaint correctly claimed that the league was under-reporting revenue (seen in the Bulls TV dispute, as well as Grantham’s allegation the teams were hiding luxury box money), which is how the NBA sets its yearly salary cap. He won a 100 million dollar decision, bumping the cap over the next two seasons.

In lieu of abolishing the salary cap, Grantham was at least able to preserve its flexibility, seen in the 1993 Chris Dudley Decision, which upheld his 11 million dollar free agent signing by the Portland Trailblazers. The Blazers signed Dudley away from the Nets, but included an opt out clause after one year, which would allow him to then resign with the Blazers at a higher number that would be permissible under, while essentially circumventing, the cap. In finagling this contract and seeing it upheld in court, Grantham was able to resist David Stern’s ongoing project as commissioner to tighten the cap’s lid.

Grantham’s downfall was an inability to hold his union, led by Buck Williams, together. He took a hardline approach to negotiation with the league, an “Us vs. Them” mentality that demanded the league agree to his terms, or he’d take his union and strike for as long as necessary to extract his demands. Grantham first took a crushing blow in court, finding in the league’s favor in 1994, when he brought an antitrust suit against the league after their current CBA had expired.

The way courts determine what protocols a labor union and their employer must proceed under is complicated, and I’m not going to wade into the intricacies of nonstatutory labor exemptions for this frivolous listicle, but basically Grantham argued in lieu of an agreement, the NBPA was left without remedy for the league’s unilateral decision how to treat its labor. While Grantham’s NBPA had been on a win streak, here, in his most crucial fight, the league prevailed. The remaining options were to decertify the union, opening the league up anew to antitrust violations (an old Fleisher threat/tactic), or come back to the table hat in hand, ready to negotiate on the league’s terms.

Grantham bemoaned his changing league, saying, “The day is gone when you could tell players to save money. You can’t do that.” What he means is the foresight, solidarity and resolve necessary to lock into a drawn out labor dispute amongst a broad spectrum of players with competing agendas no longer exists, presumably to the owner’s delight. The simple truth is players don’t want to strike. They want their money. Future percentages on league BRI are an abstraction. Car payments, alimony, mortgages, these are immediate, tangible concerns.

The CBA expired in 1994. Grantham agreed to a one year extension with the league to avoid a lockout and hammer out a new agreement. After the final game of the season in 1995, the NBA announced its first work stoppage. Grantham was already out as NBPA head, with Simone Gourdine doing his job, trading dollars up front for long term, structural change.

What would it have meant to truly represent the players interests in this dispute? To do what the group of impatient, reactionary players were demanding? Effective Union heads are also responsible for communicating their vision, getting their constituencies on their sides, and whipping votes when it is gut check time. Grantham was clearly not up to the task in this respect. He was allowed to resign from his position as the first NBPA Executive Director, but it was understood he was forced out by the players in the lead up to 1995’s offseason strike.

But it’s hard to argue with his vision for the future of labor relations in the league and what it would have meant to future generations of players had the NBPA been able to hold their ground. A long and messy battle in court, but one that could have forever changed the landscape of the league, given players unfettered autonomy over their careers from rookie to retirement, completely changed the wage scale, and realized the true intention of the Robertson Decision. He lost because he demanded, and fought for more than the players were willing to fight for themselves.