As the planet reels in anxiety and grief, Matty Healy sounds surprisingly calm, almost as if he’d expected this, or certainly hadn’t been entirely surprised by it. “It is a very, very odd time,” he says over the phone from the recording studio in the English countryside where he’s been quarantining with the drummer-producer George Daniel, his bandmate in the 1975 and principal creative collaborator. And yet “I don’t feel lonely in this,” Healy adds. “That can be one of the things I really struggle with. But I feel like we’re all in this together. Humanity is quite engaged at the moment.”

It’s as if all the disquietude that’s bedeviled him and fueled his creativity has found its match in this current moment. Healy has always tackled big issues (climate change, mental health, politics) through pop music, and his band’s latest, Notes on a Conditional Form, out May 22, is a wildly ambitious exploration of existential anxiety. Healy, 31, is a clever pop mind, and the 1975’s music feels like a scavenger hunt through his subconscious. That intimacy with his own angst is partly why his just-as-angsty young fans love and obsess over him (his lanky rock-star looks play a role in this too).

It’s no secret that he’s used narcotics. Slow-down-and-numb drugs, anything that knocked him out. He was “never the cocaine-y party guy at five in the morning,” he says. “Unconsciousness is my drug of choice.” He feels too awake to too many things: Heroin was a means by which he could tamp down the endless timeline of discontent unfurling in his head. But he has a way of making even smoking heroin sound like a chore. “You’ve got to wake up in the morning, smoke it again, keep smoking it all day, until the next day, and maybe then you can start falling asleep and not feeling sick,” he explains methodically. “But if you just smoke it at night and go to bed … Ugh, so bad. You’ll wake up with the worst hangover ever. And I can’t deal with hangovers.”

When I first met him in November, backstage before a 1975 show in New Jersey, he still had the floppy brown curls he’s since cut off and was wearing a floor-length floral dress and green Chuck Taylors. At that point, climate change was Healy’s big-picture melancholy. He told me then that “if the world does go to shit, I’ll just fucking do drugs.” With the world, in fact, going to shit, he admits he was tempted. “It felt like an excuse to be high all the time,” he says. “But I’ve managed not to.” He’s gained a sense of mission. “We need to sacrifice things; there’s no room for passive shit anymore,” he continues. “And that means adhering to the necessities of the planet. It’s a new time now.” From one of rock music’s most notorious egoists, this sounds a little like perspective.

Daniel and Healy started playing music with two other high-school friends, guitarist Adam Hann and bassist Ross MacDonald, in 2002. Before they settled on the 1975 — the name doesn’t specifically have a meaning — they called themselves a few things; Me and You Versus Them, Drive Like I Do. This was in the small English town of Wilmslow, an upscale suburb of Manchester.

The wider world first heard of them in 2013 with their eponymous debut LP, which reached No. 1 in the U.K. They’ve had a fast run after that: 2016’s chart-topping I Like It When You Sleep, for You Are So Beautiful Yet So Unaware of It and 2018’s critically praised A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships, which coincided with Healy’s brief relapse. But he says he’s been clean for a year now, which has “massively changed the band dynamic,” says Daniel. When Healy isn’t using drugs, “the window for his focus gets a lot bigger. It’s not a battle.”

Until now, every 1975 album began with a self-titled theme song, albeit a nearly lyrically identical and atmospheric one. But for Notes, Healy begins with Greta Thunberg delivering a five-minute screed on ecological crisis. Every night at his band’s shows this past fall, when he should have been taking an encore, Healy instead returned to the stage by himself, sat on the band’s monitors with his back to the audience, and played her speech.

“All of our records are just about what I’m scared of, what I’m excited about, what turns me on, what I think is funny,” he says. His songs seethe with paranoia, not catharsis, with lyrics that resonate with its youthful fan base’s discontent and then sells it, hard, with undeniable pop hooks — on the recent single “People,” he sings, “Well, my generation wanna fuck Barack Obama / Living in a sauna with legal marijuana.”

It’s the kind of music that inspires fans to stop him on the street and tell him their dark personal secrets; he sometimes finds the devotion a bit much. (“On the first tour, I saw a kid with a 1975 neck tattoo,” Healy recalls. “It’s fucking wild.”) But what does he expect when he’s made a career of sharing his? Modern stardom requires authenticity and self-revelation, which means constant engagement with fans on social media. One day’s Instagram performance earlier this year found Healy, who has 1.4 million followers, serving up a meme critiquing neoliberalism, showing a dog getting hit in the face by a Frisbee, and then pivoting to a collection of band shirts showcasing

his alt-rock bona fides (Pantera, Jimmy Eat World, the Lemonheads). A Brief Inquiry includes a spoken-word track detailing a man for whom the internet “was his friend / You could say his best friend / They would play with each other every day / Watching videos of humans doing all sorts of things / Having sex with each other.”

When the 1975 first emerged, they were an almost entirely anonymous entity: The aesthetic for the band’s first four EPs, all released in under a year starting in 2012, as well as their 2013 debut album, seemed deliberately aloof from the sexy hard sell. But it soon turned out that Healy was a natural on Twitter.

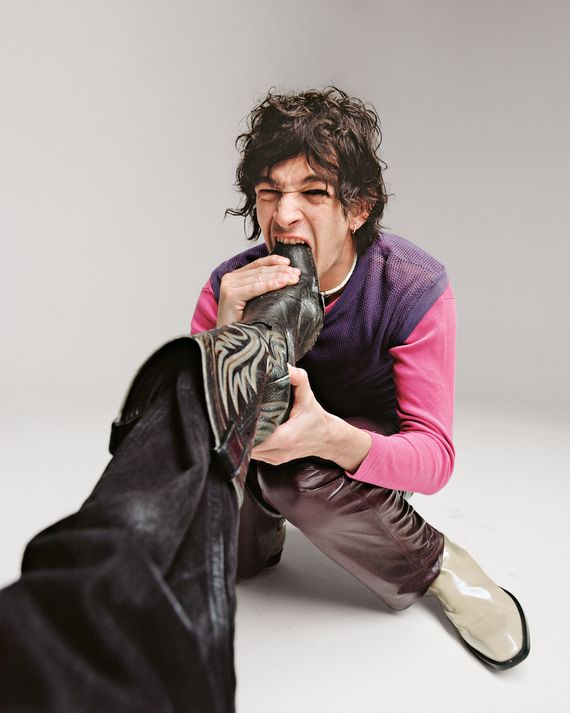

Photo: Louie Banks

Healy is prone to rant about the way in which social media is like a drug addiction, but he’s proud to point out that the 1975 was early to Instagram. As a social-media celebrity, Healy gets into beefs: In December, Maroon 5 tweeted at the 1975, accusing them of poaching the art for the single “Me and You Together Song” from Kara’s Flowers, Adam Levine’s early-career band. To which Healy clapped back, “I don’t know what the fuck that is but I love that song about being in a phone box or whatever it is.” Another widely derided incident occurred as COVID-19 kicked into high gear. With the virus decimating many musicians’ abilities to earn income touring, Healy seemed to mock those seeking alternative revenue streams. “Stop telling people to support you we don’t want your EP and zine bundle now Laura we’re going to die,” he tweeted before deleting it and issuing a non-apology: “I’m not sorry I’m just bored.”

His ego can get him into trouble. During promotion for A Brief Inquiry, he told Vulture, “Give me a better [album]. Show me the other big band who’s fucking amazing.” People aren’t always as impressed with him as he is. Following the 1975’s debut performance on Saturday Night Live in 2016, when Healy appeared shirtless and writhed across the stage, the Village Voice dubbed the performance “pleasurable, polarizing, [and] punch-your-TV obnoxious.” One Twitter user went so far as to write, “After watching SNL, I don’t think I’ve ever hated a person more than the lead singer of the 1975.”

Healy says he’s learning to take it all in stride. “As you get a bit older, you just can’t be hassled with that fucking shit. You don’t need to know what some guy thinks about you.”

Healy had some familiarity with how to be famous. His parents are British TV stars Tim Healy (Auf Wiedersehen, Pet) and Denise Welch (Waterloo Road). After Healy and his bandmates graduated from Wilmslow High School, whose younger alumni include Harry Styles, their band was rejected by several major record labels. Their manager, Jamie Oborne, eventually began self-financing their projects and formed Dirty Hit Records to release their music. (The 1975 now have a distribution deal in the U.S. with Interscope Records.)

At the start, they were essentially an emo band, an of-the-moment offshoot of Healy and Daniel’s teenage obsession with noise rock and punk. Healy describes their teenage selves as “maybe a bit pretentious. Super into philosophy and really left-field German house music and other really weird shit.” Like so many arts-inclined adolescents before him, Healy found romance in the writings of writers like Kerouac and Burroughs, who notably also romanticize seedy drug use.

But, pretentiousness aside, they always knew they were destined to be pop stars. Otherwise, why bother? “We’ve always wanted to be truly subversive,” says Healy. “And doing something like fracturing pop music, fucking with mainstream discourse with your art, that’s punk for me. Being a loud band that no one listens to is great. It’s cool. But it’s not aspirational; it’s a hobby.”

Photo: Louie Banks

By the time they recorded I Like It When You Sleep, they’d transformed their sound into outré pop, with sleek dance-rock grooves, splashy synths, and funky bass lines. It was around this time Healy got heavily into drugs. “I used to love listening to insane noise music and then go out into dodgy parts of East London and score,” he remembers. He needed something to block out the mania of his new life. “It’s all self-medication,” he surmises. “You don’t really want to think about why you don’t like the way that you feel because that takes a long time and it’s probably pretty ugly.”

Healy entered rehab in Barbados at the end of the I Like It When You Sleep’s tour cycle in November 2017, following a rant over dinner to his bandmates while under the influence of benzodiazepine. Despite their pleas to him to stop using, he told them he intended to keep smoking heroin. The next day, “I realized that was absolute fucking bullshit. So I went downstairs and told George I should go to rehab,” he told Billboard. Once he was out, in January 2018, he returned to work on A Brief Inquiry. Pitchfork named the album’s disquieting centerpiece, “Love It If You Made It,” its top track of 2018.

He insists his drug use was an on-and-off thing, “something I used to pick up and put down.” According to the U.K. press, it was his partying that split up his four-year relationship with model Gabriella Brooks. But “it hasn’t fractured any of my really serious relationships,” he says. “Any transient relationships that I have are just not there anymore. So you have your really, really close friends and family and they get it. They’re going to get it that you can’t come for Christmas.” Most recently, there have been rumors that he is dating FKA Twigs, who appears on the Notes track “If You’re Too Shy (Let Me Know),” though when asked about her, Healy deflects: “When it comes to those kinds of intimate parts of my personal life, it’s probably best for me to just leave it out.”

Looking back at his decision to get clean, Healy concluded it was as much in service to the 1975 as himself: If he had remained a junkie, “it would have made me an actual cliché. And then all of my jokes in my songs about being a cliché wouldn’t land.”

In quarantine, Healy says, he’s been listening to the new album and he can’t help but feel as if it carries new meaning. Lots to ruminate on since he tweeted on March 13, “I don’t like going outside, so bring me everything here,” right before he left the world for studio lockdown.

“Obviously, I wrote the album without the knowledge of [the pandemic] happening,” he says. But upon reflection, there was an almost eerie feeling when recording it, he adds, like “just before it rains. It felt like we could see the cows moving or something. It felt like the moment will not hold, surely. There had to be some kind of mass event or mass cultural shift.” They kept pushing back release dates, endlessly tinkering before finally turning in the album only weeks before the virus overtook the planet — it was all, he now senses, leading up to, well, something. According to George Daniel, the album “feels like a warm hug.”

*This article appears in the May 11, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Now!