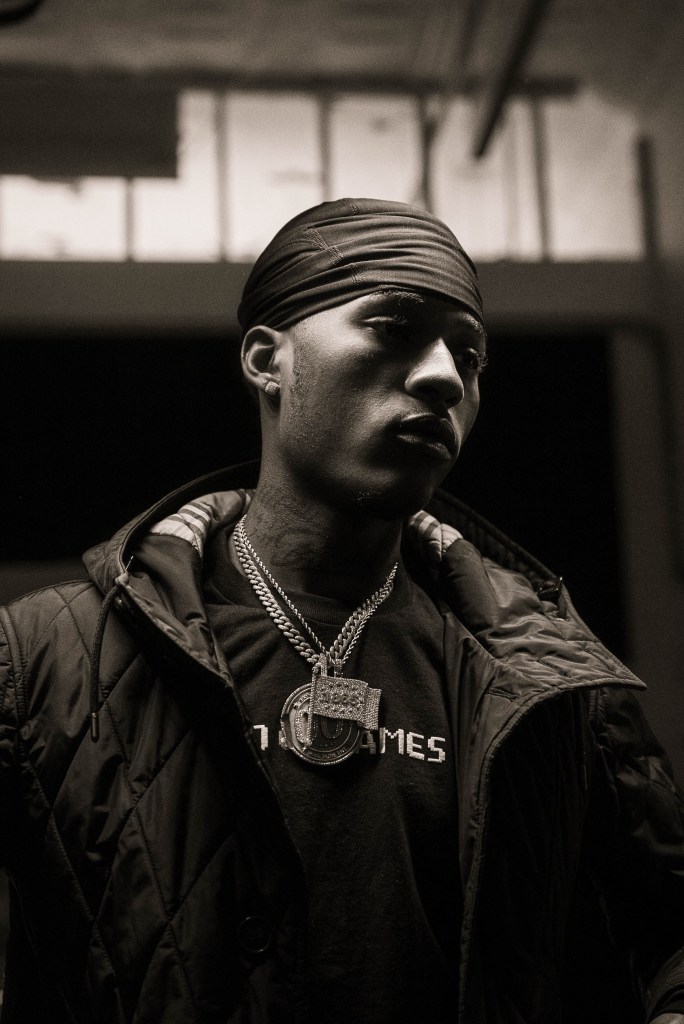

Credit: Amanda B Films

As Bandmanrill stands for his Club Godfather’s album cover, face stoic aimed down in a black-and-white pinstripe suit, thousands of dollars waving in his blazer’s front flap pocket, he imagines himself as Newark’s Don Vito Corleone. Although you can’t see Marlon Brando’s signature black bowtie, two frosted 100% Pure and 1865 Black Flag pendants hang down Rill’s cuban link. These accessories are symbols of respect – age and legacy within the mob and family within the music industry.

The infamous leader of New Jersey’s music scene is somewhere between James Gandolfini’s Tony Soprano and the Godfather himself, Siril Pettus. Where The Godfather’s signature logo features a puppeteer’s hand holding a wooden cross, Club Godfather’s logo has its hand holding the cross with four fingers, leaving the middle finger up as a “fuck you” to tradition. At only 20 years-old, Bandmanrill did what no other rapper had thought to do before: he transformed a Jersey club beat into a springy, sample-drill prototype: “Heartbroken.”

In the late 2000s, Newark kept its focus on electronic music. Originally dubbed “Brick City club,” DJ Tameil, Tim Dolla and Mike V looked towards Baltimore club’s mix of house with hip-hop to upstart their own subgenre. Jersey club introduced an antsy, fast-paced groove of around 130-140 BPM, countering Baltimore club’s 80 BPM. These songs are filled with repeated soundbites, from single word ad libs like “dick” or “hey” to gunshot sound effects.

Artists in the Jersey club scene chop up samples from popular rap and R&B songs, with seminal tracks using Baltimore-derived kick drum triplets from Tapp’s “Dikkontrol” and the breaks from Lyn Collins’ “Think (About It).” DJ Tameil made some of the first Jersey club tracks in his 2001 Dat Butt EP, sampling contemporary songs such as “U Got It Bad” by Usher. Jersey club continued to stray further and further from its Baltimore influence, going into a culture of making music centered on dance moves, as seen with Tim Dolla’s regional hit, “Swing Dat Shyt.”

Even in 2022, Jersey club has only recently been discovered in pop culture. When Drake sampled “Some Cut” by Trillville on his song “Currents” off of Honestly, Nevermind, the unacquainted were caught off guard by the “annoying squeaky bed sounds.” Bandmanrill reveals that the recent induction of Jersey drill originally received mixed reactions in his hometown, with some hailing him as a visionary while others disapproved of his lack of traditionalism.

In Bandmanrill’s aptly titled single, “I Am Newark,” the song begins with a struggling voice attempting to sound out the name of his birthplace. The TikTok soundbite rhetorically asks, “Does anybody even come over here?” before entering a joint beat produced by Project X, MC Vertt, and Rrodney. Bandmanrill claims his city and its upcoming style of rap over “ayes,” bed squeaks, and sporadic bass drum hits.

When I walked into the Record Plant to interview Bandmanrill, there’s an indoor basketball court, an open bar, and a sleek black grand piano radiating in the corner. Justin Timberlake recorded FutureSex/LoveSounds here. Ariana Grande recorded Thank U, Next here. Frank Ocean recorded Channel Orange here. This same studio was about to hold a listening party for Bandmanrill’s debut album, Club Godfather, flipping snippets from that same breed of pop music to showcase the emerging sound of New Jersey hip-hop.

As his leg shakes throughout the interview, you can tell that Bandmanrill – the artist who rapidly flows over high-tempo club beats – was not meant to sit down and answer questions in a silent room. Bandmanrill needs stimulation. He needs action and excitement. With an abundance of pride for his city, he boasts the exact type of energy that you would expect from a young adult who’s been listening to club music since the day he was born. Bandmanrill carries the energy of Newark’s next generation. – Yousef Srour

What’s an average day in Newark like?

Bandmanrill: You might just come outside. Whole lot of stolen cars are driving past you, going fast as hell. Going to certain places, you might see somebody get shot. How it is everywhere else. Just poverty and shit.

How did that influence you as a person?

Bandmanrill: I grew up fast. When you see stuff young, you learn shit young. I was a product of my environment to a certain extent; I always used my environment to my advantage type-shit.

How does it feel to be putting on the city?

Bandmanrill: I feel good as hell. I’ve got people behind me. Artists are really trying to put the spotlight on where I’m from because no one else really did it before. It’s crazy because I always said, “Somebody needs to do this,” and I’m the n***a that’s doing it. Everything that Newark needs, I’m trying to do.

With the other people that tried to rap over club beats, what did you learn from them?

Bandmanrill: One person who tried to do it, his name was Unicorn[151]. He made it far, but he didn’t really make it far far. He’s from Jersey too; he’s from East Orange. I didn’t really know about him until about a month after I made “Heartbroken.” People started telling me, “Nah, he was doing this first. He was the first person to ever rap on a club beat.” I wasn’t even familiar with that at all.

Do you think the energy of your music matches the energy of Newark?

Bandmanrill: For sure. It’s definitely high-tempo. It’s club music, that’s what we come from, that’s our culture. An average day in Newark, going back to that, at the end of the day you might go back to a party and you’ll hear the same type of beats that I’m rapping over.

Your dad was a DJ. Did you feel like music was inside of you when you were growing up?

Bandmanrill: I definitely always had music in me. I’ve got eleven brothers and ten of them rap. I’m the youngest and I never really wanted to rap. I was on some boxing shit. When I first started, I could instantly see that I had talent with the shit. Anybody else that was doing it didn’t sound like how I sounded. It was like, “Yeah, I could probably make it far with this, for real.”

What was it like growing up with eleven brothers?

Bandmanrill: When I was young, I didn’t grow up with my eleven brothers. It was me, my mother, my father, my grandfather, my grandmother, my sister, my auntie, her son, her brother, and my uncle. As I got older, they started moving out and it was just me, my mother, my sister and her daughter, her n***a, and my father ended up leaving. I always had two or three brothers around. I always see the other ones here and there.

I heard they started the SoSouth movement.

Bandmanrill: It was a movement called SoSouth. My brother had a camera and shit; he used to be recording all the videos. I used to sneak into his room and look at all the videos. He used to have all the money and all the bitches and shit. When I was young, I always wanted to be like that; I always wanted to be a star. I didn’t necessarily know I wanted to be in rapping. The rapper lifestyle was always intriguing to me though.

So SoSouth was more of a musical movement?

Bandmanrill: I’m from the South of Newark, so it was a whole bunch of people that was SoSouth, it was the South versus everybody. It was the South movement and that was their shit.

Was your mom into music at all?

Bandmanrill: My mom loved music. She used to always be cleaning the house, listening to my father playing music or bumping music in her headphones.

Is there anything you remember her playing that stuck with you?

Bandmanrill: My mother used to play that Adele song. There’s this one song that she put me on, “Too Close” by Alex Clare. She be playing all kinds of shit. She mainly be playing house music and shit though.

I think that’s interesting because sometimes in your music there’ll be that slower sample in it, where you’ll add in that poppier sound. Do you do that to balance the music out?

Bandmanrill: Definitely to balance it out. It just depends on the vibe of the song. The best thing about Jersey club is that you can make it do whatever: make it sound real poppy, real clubby, or even a little more drilly. Jersey club, you can really make it sound like anything.

Were you listening to drill when you were growing up?

Bandmanrill: I was listening to Chicago drill like Chief Keef, L’A Capone, Shit like that. When New York came out with drill, Curly Savv, Bam Bino, 22Gz, Sheff G. That’s the drill that I was familiar with.

How about crunk music? Were you ever into that?

Bandmanrill: I don’t know about crunk music, but I know that’s Southern – I don’t want to say Southern because I don’t know where it originated, but I believe it was Memphis. That crunk shit is definitely similar to Jersey club music because that shit’s real uptempo and it’ll get you hype. I fuck with that shit for sure.

What was the reception like in Jersey when Drake hopped on a Jersey club beat?

Bandmanrill: Everyone was asking me, “Damn. Why aren’t you on there?” “N***a, I don’t know. Ask that n***a.” It is what it is. I salute Drake for getting on the wave. He put a lot of eyes on the movement.

Do you think it helped propel your music?

Bandmanrill: Yeah, it definitely did, slightly. Just because of the sound, getting more people familiar with the sound, getting people talking.

We’re in LA, you’ve rapped about Nipsey Hussle in your music, how has he resonated with you as a person?

Bandmanrill: I fuck with how he’s a leader. I like n****s that believe in their own shit and don’t follow behind nobody’s orders and just want to be rich and take over. When Nip got his money up and bought a store in that same complex that he was standing in front of, that’s inspiring. A lot of people in the hood got the mindset of getting that money, but a lot of people don’t have that mindset of what are you going to do after you get that money, what are you going to do for your kids? He thought about everything. He was a smart hood n***a.

What has boxing taught you?

Bandmanrill: Discipline. For example, I smoke a lot now – when I was boxing I wasn’t smoking – but if I want to stop smoking right now, I can. It taught me, mentally, you don’t really need nothing. Everything’s mental. As long as you’re strong enough, you’re good. Stay in good shape, you’ll be fine.

How have you applied that same discipline to rapping?

Bandmanrill: Just trying to stay in the stu. When I do something, I’m always going to put my 120% into it. When I was boxing, I was doing that shit 120%, waking up before school to go run at 4, go to school at 6 and go to the gym right after. It’s the same thing with rap: wake up early, probably write a song, go to the stu, make mad songs, and do the same thing everyday. Just being disciplined and staying focused.

Do you think that makes you a better rapper?

Bandmanrill: For sure. Practice makes perfect. Everything you keep doing, you’re always going to get better at it. My coach always used to tell me, “You don’t become a pro at something until you put your 10,000 hours into it.” I’ve got to do double that, 10x that, to become better than a pro.

Can you describe to me the first time you started rapping?

Bandmanrill: I started rapping in my house in my own studio. I was real comfortable. My only problem when I first started is that I was unsure if I was good because I ain’t know what good was. When I was hearing other people’s shit, I was like, “There’s no way that you can like this shit and not like my shit.” I just went off that.

How about when you first started rapping over Jersey club beats? When did that first happen?

Bandmanrill: That was my fifth or sixth song that I put out, ever. I was talking to my mans one day, and he was just like, “Yo, why nobody ever rap on a club beat before?” I was like, “Y’know, that’s a good question.” We’re from Jersey and I’m just sitting around thinking about it like, “You’re right.” I just did it, and to be real with you, I didn’t even finish the song. I just recorded 15 seconds of the song and put it on TikTok. When I put it on TikTok, it just blew up, and that’s when I went and finished the song.

Was the reception on TikTok different than the reception in Jersey?

Bandmanrill: Yeah, definitely. When it was first going off, the reception on TikTok was going so crazy, but the reception in Jersey was like, “Nah, this n***a rapping on club… He going off club…” A lot of n****s were haters.

Did the reception on TikTok push you to keep going?

Bandmanrill: It showed me that shit could happen. My whole life I’ve just been waiting on that one moment that showed me that shit could work. That was that moment.

With TikTok, did you have a following before you started rapping?

Bandmanrill: Yeah. I’m just a funny n***a. I used to make little funny videos that you would only really understand if you were from Newark or Jersey. When I built up my following, obviously my following would be just straight Newark and Jersey because that’s what I make content for. I just started making music and I was decent, so people was fucking with me.

You ride or die for Jersey. Do you think that sets you apart from a lot of other rappers?

Bandmanrill: I’m real thorough. I always stand up for where I’m from or what I believe in For Jersey, it’s about time that somebody steps up for Jersey because nobody’s done it. Jersey just needs a forefront. Everybody’s afraid to do it, but I’m not.

How did Club Godfather come into fruition?

Bandmanrill: Shit just locked in with my producer. I didn’t really lock in on the project. I go to the studio everyday for at least 6 to 12 hours. Over time, we just listened to all the songs like, “This the best song. This the best song. This the best song.” We just threw them all on a project that we felt had the best ones and that’s the project.

Do you think you’re always going to be rapping over club beats?

Bandmanrill: Probably, yeah. I want the industry to be rapping over club beats. You can put a club beat on anything, melodies or drill beats; you can put it on anything and it’s going to turn your beat into something totally different.

What do you want to accomplish in the next five years?

Bandmanrill: I want to be the biggest rapper in the world. Now, I’ve reached my goal of being the biggest rapper in Jersey, and it’s time to take over the world now. Everyone wants to be a rapper, but I want to be the rapper, the one that’s different than all the rest and made it further than everybody else. I feel like I got the opportunity to do that with my sound that I brought to the industry and getting everybody on there and showing love to where I’m from, Newark, Jersey and our culture.

What would make you feel like you’ve made it further than everyone else?

Bandmanrill: When everytime I drop an album, it goes #1 every time.

After people listen to Club Godfather, what do you want them to know about Bandmanrill?

Bandmanrill: That this is just volume one of this club genre and every tape after this is going to get better and better and better, just reinventing more club stuff. You might even hear some stuff that’s not club, just improving and getting better as an artist.

How did that influence you as a person?

Bandmanrill: I grew up fast. When you see stuff young, you learn shit young. I was a product of my environment to a certain extent; I always used my environment to my advantage type-shit.

How does it feel to be putting on the city?

Bandmanrill: I feel good as hell. I’ve got people behind me. Artists are really trying to put the spotlight on where I’m from because no one else really did it before. It’s crazy because I always said, “Somebody needs to do this,” and I’m the n***a that’s doing it. Everything that Newark needs, I’m trying to do.

With the other people that tried to rap over club beats, what did you learn from them?

Bandmanrill: One person who tried to do it, his name was Unicorn[151]. He made it far, but he didn’t really make it far far. He’s from Jersey too; he’s from East Orange. I didn’t really know about him until about a month after I made “Heartbroken.” People started telling me, “Nah, he was doing this first. He was the first person to ever rap on a club beat.” I wasn’t even familiar with that at all.

Do you think the energy of your music matches the energy of Newark?

Bandmanrill: For sure. It’s definitely high-tempo. It’s club music, that’s what we come from, that’s our culture. An average day in Newark, going back to that, at the end of the day you might go back to a party and you’ll hear the same type of beats that I’m rapping over.

Your dad was a DJ. Did you feel like music was inside of you when you were growing up?

Bandmanrill: I definitely always had music in me. I’ve got eleven brothers and ten of them rap. I’m the youngest and I never really wanted to rap. I was on some boxing shit. When I first started, I could instantly see that I had talent with the shit. Anybody else that was doing it didn’t sound like how I sounded. It was like, “Yeah, I could probably make it far with this, for real.”

What was it like growing up with eleven brothers?

Bandmanrill: When I was young, I didn’t grow up with my eleven brothers. It was me, my mother, my father, my grandfather, my grandmother, my sister, my auntie, her son, her brother, and my uncle. As I got older, they started moving out and it was just me, my mother, my sister and her daughter, her n***a, and my father ended up leaving. I always had two or three brothers around. I always see the other ones here and there.

I heard they started the SoSouth movement.

Bandmanrill: It was a movement called SoSouth. My brother had a camera and shit; he used to be recording all the videos. I used to sneak into his room and look at all the videos. He used to have all the money and all the bitches and shit. When I was young, I always wanted to be like that; I always wanted to be a star. I didn’t necessarily know I wanted to be in rapping. The rapper lifestyle was always intriguing to me though.

So SoSouth was more of a musical movement?

Bandmanrill: I’m from the South of Newark, so it was a whole bunch of people that was SoSouth, it was the South versus everybody. It was the South movement and that was their shit.

Was your mom into music at all?

Bandmanrill: My mom loved music. She used to always be cleaning the house, listening to my father playing music or bumping music in her headphones.

Is there anything you remember her playing that stuck with you?

Bandmanrill: My mother used to play that Adele song. There’s this one song that she put me on, “Too Close” by Alex Clare. She be playing all kinds of shit. She mainly be playing house music and shit though.

I think that’s interesting because sometimes in your music there’ll be that slower sample in it, where you’ll add in that poppier sound. Do you do that to balance the music out?

Bandmanrill: Definitely to balance it out. It just depends on the vibe of the song. The best thing about Jersey club is that you can make it do whatever: make it sound real poppy, real clubby, or even a little more drilly. Jersey club, you can really make it sound like anything.

Were you listening to drill when you were growing up?

Bandmanrill: I was listening to Chicago drill like Chief Keef, L’A Capone, Shit like that. When New York came out with drill, Curly Savv, Bam Bino, 22Gz, Sheff G. That’s the drill that I was familiar with.

How about crunk music? Were you ever into that?

Bandmanrill: I don’t know about crunk music, but I know that’s Southern – I don’t want to say Southern because I don’t know where it originated, but I believe it was Memphis. That crunk shit is definitely similar to Jersey club music because that shit’s real uptempo and it’ll get you hype. I fuck with that shit for sure.

What was the reception like in Jersey when Drake hopped on a Jersey club beat?

Bandmanrill: Everyone was asking me, “Damn. Why aren’t you on there?” “N***a, I don’t know. Ask that n***a.” It is what it is. I salute Drake for getting on the wave. He put a lot of eyes on the movement.

Do you think it helped propel your music?

Bandmanrill: Yeah, it definitely did, slightly. Just because of the sound, getting more people familiar with the sound, getting people talking.

We’re in LA, you’ve rapped about Nipsey Hussle in your music, how has he resonated with you as a person?

Bandmanrill: I fuck with how he’s a leader. I like n****s that believe in their own shit and don’t follow behind nobody’s orders and just want to be rich and take over. When Nip got his money up and bought a store in that same complex that he was standing in front of, that’s inspiring. A lot of people in the hood got the mindset of getting that money, but a lot of people don’t have that mindset of what are you going to do after you get that money, what are you going to do for your kids? He thought about everything. He was a smart hood n***a.

What has boxing taught you?

Bandmanrill: Discipline. For example, I smoke a lot now – when I was boxing I wasn’t smoking – but if I want to stop smoking right now, I can. It taught me, mentally, you don’t really need nothing. Everything’s mental. As long as you’re strong enough, you’re good. Stay in good shape, you’ll be fine.

How have you applied that same discipline to rapping?

Bandmanrill: Just trying to stay in the stu. When I do something, I’m always going to put my 120% into it. When I was boxing, I was doing that shit 120%, waking up before school to go run at 4, go to school at 6 and go to the gym right after. It’s the same thing with rap: wake up early, probably write a song, go to the stu, make mad songs, and do the same thing everyday. Just being disciplined and staying focused.

Do you think that makes you a better rapper?

Bandmanrill: For sure. Practice makes perfect. Everything you keep doing, you’re always going to get better at it. My coach always used to tell me, “You don’t become a pro at something until you put your 10,000 hours into it.” I’ve got to do double that, 10x that, to become better than a pro.

Can you describe to me the first time you started rapping?

Bandmanrill: I started rapping in my house in my own studio. I was real comfortable. My only problem when I first started is that I was unsure if I was good because I ain’t know what good was. When I was hearing other people’s shit, I was like, “There’s no way that you can like this shit and not like my shit.” I just went off that.

How about when you first started rapping over Jersey club beats? When did that first happen?

Bandmanrill: That was my fifth or sixth song that I put out, ever. I was talking to my mans one day, and he was just like, “Yo, why nobody ever rap on a club beat before?” I was like, “Y’know, that’s a good question.” We’re from Jersey and I’m just sitting around thinking about it like, “You’re right.” I just did it, and to be real with you, I didn’t even finish the song. I just recorded 15 seconds of the song and put it on TikTok. When I put it on TikTok, it just blew up, and that’s when I went and finished the song.

Was the reception on TikTok different than the reception in Jersey?

Bandmanrill: Yeah, definitely. When it was first going off, the reception on TikTok was going so crazy, but the reception in Jersey was like, “Nah, this n***a rapping on club… He going off club…” A lot of n****s were haters.

Did the reception on TikTok push you to keep going?

Bandmanrill: It showed me that shit could happen. My whole life I’ve just been waiting on that one moment that showed me that shit could work. That was that moment.

With TikTok, did you have a following before you started rapping?

Bandmanrill: Yeah. I’m just a funny n***a. I used to make little funny videos that you would only really understand if you were from Newark or Jersey. When I built up my following, obviously my following would be just straight Newark and Jersey because that’s what I make content for. I just started making music and I was decent, so people was fucking with me.

You ride or die for Jersey. Do you think that sets you apart from a lot of other rappers?

Bandmanrill: I’m real thorough. I always stand up for where I’m from or what I believe in For Jersey, it’s about time that somebody steps up for Jersey because nobody’s done it. Jersey just needs a forefront. Everybody’s afraid to do it, but I’m not.

How did Club Godfather come into fruition?

Bandmanrill: Shit just locked in with my producer. I didn’t really lock in on the project. I go to the studio everyday for at least 6 to 12 hours. Over time, we just listened to all the songs like, “This the best song. This the best song. This the best song.” We just threw them all on a project that we felt had the best ones and that’s the project.

Do you think you’re always going to be rapping over club beats?

Bandmanrill: Probably, yeah. I want the industry to be rapping over club beats. You can put a club beat on anything, melodies or drill beats; you can put it on anything and it’s going to turn your beat into something totally different.

What do you want to accomplish in the next five years?

Bandmanrill: I want to be the biggest rapper in the world. Now, I’ve reached my goal of being the biggest rapper in Jersey, and it’s time to take over the world now. Everyone wants to be a rapper, but I want to be the rapper, the one that’s different than all the rest and made it further than everybody else. I feel like I got the opportunity to do that with my sound that I brought to the industry and getting everybody on there and showing love to where I’m from, Newark, Jersey and our culture.

What would make you feel like you’ve made it further than everyone else?

Bandmanrill: When everytime I drop an album, it goes #1 every time.

After people listen to Club Godfather, what do you want them to know about Bandmanrill?

Bandmanrill: That this is just volume one of this club genre and every tape after this is going to get better and better and better, just reinventing more club stuff. You might even hear some stuff that’s not club, just improving and getting better as an artist.

How does it feel to be putting on the city?

Bandmanrill: I feel good as hell. I’ve got people behind me. Artists are really trying to put the spotlight on where I’m from because no one else really did it before. It’s crazy because I always said, “Somebody needs to do this,” and I’m the n***a that’s doing it. Everything that Newark needs, I’m trying to do.

With the other people that tried to rap over club beats, what did you learn from them?

Bandmanrill: One person who tried to do it, his name was Unicorn[151]. He made it far, but he didn’t really make it far far. He’s from Jersey too; he’s from East Orange. I didn’t really know about him until about a month after I made “Heartbroken.” People started telling me, “Nah, he was doing this first. He was the first person to ever rap on a club beat.” I wasn’t even familiar with that at all.

Do you think the energy of your music matches the energy of Newark?

Bandmanrill: For sure. It’s definitely high-tempo. It’s club music, that’s what we come from, that’s our culture. An average day in Newark, going back to that, at the end of the day you might go back to a party and you’ll hear the same type of beats that I’m rapping over.

Your dad was a DJ. Did you feel like music was inside of you when you were growing up?

Bandmanrill: I definitely always had music in me. I’ve got eleven brothers and ten of them rap. I’m the youngest and I never really wanted to rap. I was on some boxing shit. When I first started, I could instantly see that I had talent with the shit. Anybody else that was doing it didn’t sound like how I sounded. It was like, “Yeah, I could probably make it far with this, for real.”

What was it like growing up with eleven brothers?

Bandmanrill: When I was young, I didn’t grow up with my eleven brothers. It was me, my mother, my father, my grandfather, my grandmother, my sister, my auntie, her son, her brother, and my uncle. As I got older, they started moving out and it was just me, my mother, my sister and her daughter, her n***a, and my father ended up leaving. I always had two or three brothers around. I always see the other ones here and there.

I heard they started the SoSouth movement.

Bandmanrill: It was a movement called SoSouth. My brother had a camera and shit; he used to be recording all the videos. I used to sneak into his room and look at all the videos. He used to have all the money and all the bitches and shit. When I was young, I always wanted to be like that; I always wanted to be a star. I didn’t necessarily know I wanted to be in rapping. The rapper lifestyle was always intriguing to me though.

So SoSouth was more of a musical movement?

Bandmanrill: I’m from the South of Newark, so it was a whole bunch of people that was SoSouth, it was the South versus everybody. It was the South movement and that was their shit.

Was your mom into music at all?

Bandmanrill: My mom loved music. She used to always be cleaning the house, listening to my father playing music or bumping music in her headphones.

Is there anything you remember her playing that stuck with you?

Bandmanrill: My mother used to play that Adele song. There’s this one song that she put me on, “Too Close” by Alex Clare. She be playing all kinds of shit. She mainly be playing house music and shit though.

I think that’s interesting because sometimes in your music there’ll be that slower sample in it, where you’ll add in that poppier sound. Do you do that to balance the music out?

Bandmanrill: Definitely to balance it out. It just depends on the vibe of the song. The best thing about Jersey club is that you can make it do whatever: make it sound real poppy, real clubby, or even a little more drilly. Jersey club, you can really make it sound like anything.

Were you listening to drill when you were growing up?

Bandmanrill: I was listening to Chicago drill like Chief Keef, L’A Capone, Shit like that. When New York came out with drill, Curly Savv, Bam Bino, 22Gz, Sheff G. That’s the drill that I was familiar with.

How about crunk music? Were you ever into that?

Bandmanrill: I don’t know about crunk music, but I know that’s Southern – I don’t want to say Southern because I don’t know where it originated, but I believe it was Memphis. That crunk shit is definitely similar to Jersey club music because that shit’s real uptempo and it’ll get you hype. I fuck with that shit for sure.

What was the reception like in Jersey when Drake hopped on a Jersey club beat?

Bandmanrill: Everyone was asking me, “Damn. Why aren’t you on there?” “N***a, I don’t know. Ask that n***a.” It is what it is. I salute Drake for getting on the wave. He put a lot of eyes on the movement.

Do you think it helped propel your music?

Bandmanrill: Yeah, it definitely did, slightly. Just because of the sound, getting more people familiar with the sound, getting people talking.

We’re in LA, you’ve rapped about Nipsey Hussle in your music, how has he resonated with you as a person?

Bandmanrill: I fuck with how he’s a leader. I like n****s that believe in their own shit and don’t follow behind nobody’s orders and just want to be rich and take over. When Nip got his money up and bought a store in that same complex that he was standing in front of, that’s inspiring. A lot of people in the hood got the mindset of getting that money, but a lot of people don’t have that mindset of what are you going to do after you get that money, what are you going to do for your kids? He thought about everything. He was a smart hood n***a.

What has boxing taught you?

Bandmanrill: Discipline. For example, I smoke a lot now – when I was boxing I wasn’t smoking – but if I want to stop smoking right now, I can. It taught me, mentally, you don’t really need nothing. Everything’s mental. As long as you’re strong enough, you’re good. Stay in good shape, you’ll be fine.

How have you applied that same discipline to rapping?

Bandmanrill: Just trying to stay in the stu. When I do something, I’m always going to put my 120% into it. When I was boxing, I was doing that shit 120%, waking up before school to go run at 4, go to school at 6 and go to the gym right after. It’s the same thing with rap: wake up early, probably write a song, go to the stu, make mad songs, and do the same thing everyday. Just being disciplined and staying focused.

Do you think that makes you a better rapper?

Bandmanrill: For sure. Practice makes perfect. Everything you keep doing, you’re always going to get better at it. My coach always used to tell me, “You don’t become a pro at something until you put your 10,000 hours into it.” I’ve got to do double that, 10x that, to become better than a pro.

Can you describe to me the first time you started rapping?

Bandmanrill: I started rapping in my house in my own studio. I was real comfortable. My only problem when I first started is that I was unsure if I was good because I ain’t know what good was. When I was hearing other people’s shit, I was like, “There’s no way that you can like this shit and not like my shit.” I just went off that.

How about when you first started rapping over Jersey club beats? When did that first happen?

Bandmanrill: That was my fifth or sixth song that I put out, ever. I was talking to my mans one day, and he was just like, “Yo, why nobody ever rap on a club beat before?” I was like, “Y’know, that’s a good question.” We’re from Jersey and I’m just sitting around thinking about it like, “You’re right.” I just did it, and to be real with you, I didn’t even finish the song. I just recorded 15 seconds of the song and put it on TikTok. When I put it on TikTok, it just blew up, and that’s when I went and finished the song.

Was the reception on TikTok different than the reception in Jersey?

Bandmanrill: Yeah, definitely. When it was first going off, the reception on TikTok was going so crazy, but the reception in Jersey was like, “Nah, this n***a rapping on club… He going off club…” A lot of n****s were haters.

Did the reception on TikTok push you to keep going?

Bandmanrill: It showed me that shit could happen. My whole life I’ve just been waiting on that one moment that showed me that shit could work. That was that moment.

With TikTok, did you have a following before you started rapping?

Bandmanrill: Yeah. I’m just a funny n***a. I used to make little funny videos that you would only really understand if you were from Newark or Jersey. When I built up my following, obviously my following would be just straight Newark and Jersey because that’s what I make content for. I just started making music and I was decent, so people was fucking with me.

You ride or die for Jersey. Do you think that sets you apart from a lot of other rappers?

Bandmanrill: I’m real thorough. I always stand up for where I’m from or what I believe in For Jersey, it’s about time that somebody steps up for Jersey because nobody’s done it. Jersey just needs a forefront. Everybody’s afraid to do it, but I’m not.

How did Club Godfather come into fruition?

Bandmanrill: Shit just locked in with my producer. I didn’t really lock in on the project. I go to the studio everyday for at least 6 to 12 hours. Over time, we just listened to all the songs like, “This the best song. This the best song. This the best song.” We just threw them all on a project that we felt had the best ones and that’s the project.

Do you think you’re always going to be rapping over club beats?

Bandmanrill: Probably, yeah. I want the industry to be rapping over club beats. You can put a club beat on anything, melodies or drill beats; you can put it on anything and it’s going to turn your beat into something totally different.

What do you want to accomplish in the next five years?

Bandmanrill: I want to be the biggest rapper in the world. Now, I’ve reached my goal of being the biggest rapper in Jersey, and it’s time to take over the world now. Everyone wants to be a rapper, but I want to be the rapper, the one that’s different than all the rest and made it further than everybody else. I feel like I got the opportunity to do that with my sound that I brought to the industry and getting everybody on there and showing love to where I’m from, Newark, Jersey and our culture.

What would make you feel like you’ve made it further than everyone else?

Bandmanrill: When everytime I drop an album, it goes #1 every time.

After people listen to Club Godfather, what do you want them to know about Bandmanrill?

Bandmanrill: That this is just volume one of this club genre and every tape after this is going to get better and better and better, just reinventing more club stuff. You might even hear some stuff that’s not club, just improving and getting better as an artist.

With the other people that tried to rap over club beats, what did you learn from them?

Bandmanrill: One person who tried to do it, his name was Unicorn[151]. He made it far, but he didn’t really make it far far. He’s from Jersey too; he’s from East Orange. I didn’t really know about him until about a month after I made “Heartbroken.” People started telling me, “Nah, he was doing this first. He was the first person to ever rap on a club beat.” I wasn’t even familiar with that at all.

Do you think the energy of your music matches the energy of Newark?

Bandmanrill: For sure. It’s definitely high-tempo. It’s club music, that’s what we come from, that’s our culture. An average day in Newark, going back to that, at the end of the day you might go back to a party and you’ll hear the same type of beats that I’m rapping over.

Your dad was a DJ. Did you feel like music was inside of you when you were growing up?

Bandmanrill: I definitely always had music in me. I’ve got eleven brothers and ten of them rap. I’m the youngest and I never really wanted to rap. I was on some boxing shit. When I first started, I could instantly see that I had talent with the shit. Anybody else that was doing it didn’t sound like how I sounded. It was like, “Yeah, I could probably make it far with this, for real.”

What was it like growing up with eleven brothers?

Bandmanrill: When I was young, I didn’t grow up with my eleven brothers. It was me, my mother, my father, my grandfather, my grandmother, my sister, my auntie, her son, her brother, and my uncle. As I got older, they started moving out and it was just me, my mother, my sister and her daughter, her n***a, and my father ended up leaving. I always had two or three brothers around. I always see the other ones here and there.

I heard they started the SoSouth movement.

Bandmanrill: It was a movement called SoSouth. My brother had a camera and shit; he used to be recording all the videos. I used to sneak into his room and look at all the videos. He used to have all the money and all the bitches and shit. When I was young, I always wanted to be like that; I always wanted to be a star. I didn’t necessarily know I wanted to be in rapping. The rapper lifestyle was always intriguing to me though.

So SoSouth was more of a musical movement?

Bandmanrill: I’m from the South of Newark, so it was a whole bunch of people that was SoSouth, it was the South versus everybody. It was the South movement and that was their shit.

Was your mom into music at all?

Bandmanrill: My mom loved music. She used to always be cleaning the house, listening to my father playing music or bumping music in her headphones.

Is there anything you remember her playing that stuck with you?

Bandmanrill: My mother used to play that Adele song. There’s this one song that she put me on, “Too Close” by Alex Clare. She be playing all kinds of shit. She mainly be playing house music and shit though.

I think that’s interesting because sometimes in your music there’ll be that slower sample in it, where you’ll add in that poppier sound. Do you do that to balance the music out?

Bandmanrill: Definitely to balance it out. It just depends on the vibe of the song. The best thing about Jersey club is that you can make it do whatever: make it sound real poppy, real clubby, or even a little more drilly. Jersey club, you can really make it sound like anything.

Were you listening to drill when you were growing up?

Bandmanrill: I was listening to Chicago drill like Chief Keef, L’A Capone, Shit like that. When New York came out with drill, Curly Savv, Bam Bino, 22Gz, Sheff G. That’s the drill that I was familiar with.

How about crunk music? Were you ever into that?

Bandmanrill: I don’t know about crunk music, but I know that’s Southern – I don’t want to say Southern because I don’t know where it originated, but I believe it was Memphis. That crunk shit is definitely similar to Jersey club music because that shit’s real uptempo and it’ll get you hype. I fuck with that shit for sure.

What was the reception like in Jersey when Drake hopped on a Jersey club beat?

Bandmanrill: Everyone was asking me, “Damn. Why aren’t you on there?” “N***a, I don’t know. Ask that n***a.” It is what it is. I salute Drake for getting on the wave. He put a lot of eyes on the movement.

Do you think it helped propel your music?

Bandmanrill: Yeah, it definitely did, slightly. Just because of the sound, getting more people familiar with the sound, getting people talking.

We’re in LA, you’ve rapped about Nipsey Hussle in your music, how has he resonated with you as a person?

Bandmanrill: I fuck with how he’s a leader. I like n****s that believe in their own shit and don’t follow behind nobody’s orders and just want to be rich and take over. When Nip got his money up and bought a store in that same complex that he was standing in front of, that’s inspiring. A lot of people in the hood got the mindset of getting that money, but a lot of people don’t have that mindset of what are you going to do after you get that money, what are you going to do for your kids? He thought about everything. He was a smart hood n***a.

What has boxing taught you?

Bandmanrill: Discipline. For example, I smoke a lot now – when I was boxing I wasn’t smoking – but if I want to stop smoking right now, I can. It taught me, mentally, you don’t really need nothing. Everything’s mental. As long as you’re strong enough, you’re good. Stay in good shape, you’ll be fine.

How have you applied that same discipline to rapping?

Bandmanrill: Just trying to stay in the stu. When I do something, I’m always going to put my 120% into it. When I was boxing, I was doing that shit 120%, waking up before school to go run at 4, go to school at 6 and go to the gym right after. It’s the same thing with rap: wake up early, probably write a song, go to the stu, make mad songs, and do the same thing everyday. Just being disciplined and staying focused.

Do you think that makes you a better rapper?

Bandmanrill: For sure. Practice makes perfect. Everything you keep doing, you’re always going to get better at it. My coach always used to tell me, “You don’t become a pro at something until you put your 10,000 hours into it.” I’ve got to do double that, 10x that, to become better than a pro.

Can you describe to me the first time you started rapping?

Bandmanrill: I started rapping in my house in my own studio. I was real comfortable. My only problem when I first started is that I was unsure if I was good because I ain’t know what good was. When I was hearing other people’s shit, I was like, “There’s no way that you can like this shit and not like my shit.” I just went off that.

How about when you first started rapping over Jersey club beats? When did that first happen?

Bandmanrill: That was my fifth or sixth song that I put out, ever. I was talking to my mans one day, and he was just like, “Yo, why nobody ever rap on a club beat before?” I was like, “Y’know, that’s a good question.” We’re from Jersey and I’m just sitting around thinking about it like, “You’re right.” I just did it, and to be real with you, I didn’t even finish the song. I just recorded 15 seconds of the song and put it on TikTok. When I put it on TikTok, it just blew up, and that’s when I went and finished the song.

Was the reception on TikTok different than the reception in Jersey?

Bandmanrill: Yeah, definitely. When it was first going off, the reception on TikTok was going so crazy, but the reception in Jersey was like, “Nah, this n***a rapping on club… He going off club…” A lot of n****s were haters.

Did the reception on TikTok push you to keep going?

Bandmanrill: It showed me that shit could happen. My whole life I’ve just been waiting on that one moment that showed me that shit could work. That was that moment.

With TikTok, did you have a following before you started rapping?

Bandmanrill: Yeah. I’m just a funny n***a. I used to make little funny videos that you would only really understand if you were from Newark or Jersey. When I built up my following, obviously my following would be just straight Newark and Jersey because that’s what I make content for. I just started making music and I was decent, so people was fucking with me.

You ride or die for Jersey. Do you think that sets you apart from a lot of other rappers?

Bandmanrill: I’m real thorough. I always stand up for where I’m from or what I believe in For Jersey, it’s about time that somebody steps up for Jersey because nobody’s done it. Jersey just needs a forefront. Everybody’s afraid to do it, but I’m not.

How did Club Godfather come into fruition?

Bandmanrill: Shit just locked in with my producer. I didn’t really lock in on the project. I go to the studio everyday for at least 6 to 12 hours. Over time, we just listened to all the songs like, “This the best song. This the best song. This the best song.” We just threw them all on a project that we felt had the best ones and that’s the project.

Do you think you’re always going to be rapping over club beats?

Bandmanrill: Probably, yeah. I want the industry to be rapping over club beats. You can put a club beat on anything, melodies or drill beats; you can put it on anything and it’s going to turn your beat into something totally different.

What do you want to accomplish in the next five years?

Bandmanrill: I want to be the biggest rapper in the world. Now, I’ve reached my goal of being the biggest rapper in Jersey, and it’s time to take over the world now. Everyone wants to be a rapper, but I want to be the rapper, the one that’s different than all the rest and made it further than everybody else. I feel like I got the opportunity to do that with my sound that I brought to the industry and getting everybody on there and showing love to where I’m from, Newark, Jersey and our culture.

What would make you feel like you’ve made it further than everyone else?

Bandmanrill: When everytime I drop an album, it goes #1 every time.

After people listen to Club Godfather, what do you want them to know about Bandmanrill?

Bandmanrill: That this is just volume one of this club genre and every tape after this is going to get better and better and better, just reinventing more club stuff. You might even hear some stuff that’s not club, just improving and getting better as an artist.

Do you think the energy of your music matches the energy of Newark?

Bandmanrill: For sure. It’s definitely high-tempo. It’s club music, that’s what we come from, that’s our culture. An average day in Newark, going back to that, at the end of the day you might go back to a party and you’ll hear the same type of beats that I’m rapping over.

Your dad was a DJ. Did you feel like music was inside of you when you were growing up?

Bandmanrill: I definitely always had music in me. I’ve got eleven brothers and ten of them rap. I’m the youngest and I never really wanted to rap. I was on some boxing shit. When I first started, I could instantly see that I had talent with the shit. Anybody else that was doing it didn’t sound like how I sounded. It was like, “Yeah, I could probably make it far with this, for real.”

What was it like growing up with eleven brothers?

Bandmanrill: When I was young, I didn’t grow up with my eleven brothers. It was me, my mother, my father, my grandfather, my grandmother, my sister, my auntie, her son, her brother, and my uncle. As I got older, they started moving out and it was just me, my mother, my sister and her daughter, her n***a, and my father ended up leaving. I always had two or three brothers around. I always see the other ones here and there.

I heard they started the SoSouth movement.

Bandmanrill: It was a movement called SoSouth. My brother had a camera and shit; he used to be recording all the videos. I used to sneak into his room and look at all the videos. He used to have all the money and all the bitches and shit. When I was young, I always wanted to be like that; I always wanted to be a star. I didn’t necessarily know I wanted to be in rapping. The rapper lifestyle was always intriguing to me though.

So SoSouth was more of a musical movement?

Bandmanrill: I’m from the South of Newark, so it was a whole bunch of people that was SoSouth, it was the South versus everybody. It was the South movement and that was their shit.

Was your mom into music at all?

Bandmanrill: My mom loved music. She used to always be cleaning the house, listening to my father playing music or bumping music in her headphones.

Is there anything you remember her playing that stuck with you?

Bandmanrill: My mother used to play that Adele song. There’s this one song that she put me on, “Too Close” by Alex Clare. She be playing all kinds of shit. She mainly be playing house music and shit though.

I think that’s interesting because sometimes in your music there’ll be that slower sample in it, where you’ll add in that poppier sound. Do you do that to balance the music out?

Bandmanrill: Definitely to balance it out. It just depends on the vibe of the song. The best thing about Jersey club is that you can make it do whatever: make it sound real poppy, real clubby, or even a little more drilly. Jersey club, you can really make it sound like anything.

Were you listening to drill when you were growing up?

Bandmanrill: I was listening to Chicago drill like Chief Keef, L’A Capone, Shit like that. When New York came out with drill, Curly Savv, Bam Bino, 22Gz, Sheff G. That’s the drill that I was familiar with.

How about crunk music? Were you ever into that?

Bandmanrill: I don’t know about crunk music, but I know that’s Southern – I don’t want to say Southern because I don’t know where it originated, but I believe it was Memphis. That crunk shit is definitely similar to Jersey club music because that shit’s real uptempo and it’ll get you hype. I fuck with that shit for sure.

What was the reception like in Jersey when Drake hopped on a Jersey club beat?

Bandmanrill: Everyone was asking me, “Damn. Why aren’t you on there?” “N***a, I don’t know. Ask that n***a.” It is what it is. I salute Drake for getting on the wave. He put a lot of eyes on the movement.

Do you think it helped propel your music?

Bandmanrill: Yeah, it definitely did, slightly. Just because of the sound, getting more people familiar with the sound, getting people talking.

We’re in LA, you’ve rapped about Nipsey Hussle in your music, how has he resonated with you as a person?

Bandmanrill: I fuck with how he’s a leader. I like n****s that believe in their own shit and don’t follow behind nobody’s orders and just want to be rich and take over. When Nip got his money up and bought a store in that same complex that he was standing in front of, that’s inspiring. A lot of people in the hood got the mindset of getting that money, but a lot of people don’t have that mindset of what are you going to do after you get that money, what are you going to do for your kids? He thought about everything. He was a smart hood n***a.

What has boxing taught you?

Bandmanrill: Discipline. For example, I smoke a lot now – when I was boxing I wasn’t smoking – but if I want to stop smoking right now, I can. It taught me, mentally, you don’t really need nothing. Everything’s mental. As long as you’re strong enough, you’re good. Stay in good shape, you’ll be fine.

How have you applied that same discipline to rapping?

Bandmanrill: Just trying to stay in the stu. When I do something, I’m always going to put my 120% into it. When I was boxing, I was doing that shit 120%, waking up before school to go run at 4, go to school at 6 and go to the gym right after. It’s the same thing with rap: wake up early, probably write a song, go to the stu, make mad songs, and do the same thing everyday. Just being disciplined and staying focused.

Do you think that makes you a better rapper?

Bandmanrill: For sure. Practice makes perfect. Everything you keep doing, you’re always going to get better at it. My coach always used to tell me, “You don’t become a pro at something until you put your 10,000 hours into it.” I’ve got to do double that, 10x that, to become better than a pro.

Can you describe to me the first time you started rapping?

Bandmanrill: I started rapping in my house in my own studio. I was real comfortable. My only problem when I first started is that I was unsure if I was good because I ain’t know what good was. When I was hearing other people’s shit, I was like, “There’s no way that you can like this shit and not like my shit.” I just went off that.

How about when you first started rapping over Jersey club beats? When did that first happen?

Bandmanrill: That was my fifth or sixth song that I put out, ever. I was talking to my mans one day, and he was just like, “Yo, why nobody ever rap on a club beat before?” I was like, “Y’know, that’s a good question.” We’re from Jersey and I’m just sitting around thinking about it like, “You’re right.” I just did it, and to be real with you, I didn’t even finish the song. I just recorded 15 seconds of the song and put it on TikTok. When I put it on TikTok, it just blew up, and that’s when I went and finished the song.

Was the reception on TikTok different than the reception in Jersey?

Bandmanrill: Yeah, definitely. When it was first going off, the reception on TikTok was going so crazy, but the reception in Jersey was like, “Nah, this n***a rapping on club… He going off club…” A lot of n****s were haters.

Did the reception on TikTok push you to keep going?

Bandmanrill: It showed me that shit could happen. My whole life I’ve just been waiting on that one moment that showed me that shit could work. That was that moment.

With TikTok, did you have a following before you started rapping?

Bandmanrill: Yeah. I’m just a funny n***a. I used to make little funny videos that you would only really understand if you were from Newark or Jersey. When I built up my following, obviously my following would be just straight Newark and Jersey because that’s what I make content for. I just started making music and I was decent, so people was fucking with me.

You ride or die for Jersey. Do you think that sets you apart from a lot of other rappers?

Bandmanrill: I’m real thorough. I always stand up for where I’m from or what I believe in For Jersey, it’s about time that somebody steps up for Jersey because nobody’s done it. Jersey just needs a forefront. Everybody’s afraid to do it, but I’m not.

How did Club Godfather come into fruition?

Bandmanrill: Shit just locked in with my producer. I didn’t really lock in on the project. I go to the studio everyday for at least 6 to 12 hours. Over time, we just listened to all the songs like, “This the best song. This the best song. This the best song.” We just threw them all on a project that we felt had the best ones and that’s the project.

Do you think you’re always going to be rapping over club beats?

Bandmanrill: Probably, yeah. I want the industry to be rapping over club beats. You can put a club beat on anything, melodies or drill beats; you can put it on anything and it’s going to turn your beat into something totally different.

What do you want to accomplish in the next five years?

Bandmanrill: I want to be the biggest rapper in the world. Now, I’ve reached my goal of being the biggest rapper in Jersey, and it’s time to take over the world now. Everyone wants to be a rapper, but I want to be the rapper, the one that’s different than all the rest and made it further than everybody else. I feel like I got the opportunity to do that with my sound that I brought to the industry and getting everybody on there and showing love to where I’m from, Newark, Jersey and our culture.

What would make you feel like you’ve made it further than everyone else?

Bandmanrill: When everytime I drop an album, it goes #1 every time.

After people listen to Club Godfather, what do you want them to know about Bandmanrill?

Bandmanrill: That this is just volume one of this club genre and every tape after this is going to get better and better and better, just reinventing more club stuff. You might even hear some stuff that’s not club, just improving and getting better as an artist.

Your dad was a DJ. Did you feel like music was inside of you when you were growing up?

Bandmanrill: I definitely always had music in me. I’ve got eleven brothers and ten of them rap. I’m the youngest and I never really wanted to rap. I was on some boxing shit. When I first started, I could instantly see that I had talent with the shit. Anybody else that was doing it didn’t sound like how I sounded. It was like, “Yeah, I could probably make it far with this, for real.”

What was it like growing up with eleven brothers?

Bandmanrill: When I was young, I didn’t grow up with my eleven brothers. It was me, my mother, my father, my grandfather, my grandmother, my sister, my auntie, her son, her brother, and my uncle. As I got older, they started moving out and it was just me, my mother, my sister and her daughter, her n***a, and my father ended up leaving. I always had two or three brothers around. I always see the other ones here and there.

I heard they started the SoSouth movement.

Bandmanrill: It was a movement called SoSouth. My brother had a camera and shit; he used to be recording all the videos. I used to sneak into his room and look at all the videos. He used to have all the money and all the bitches and shit. When I was young, I always wanted to be like that; I always wanted to be a star. I didn’t necessarily know I wanted to be in rapping. The rapper lifestyle was always intriguing to me though.

So SoSouth was more of a musical movement?

Bandmanrill: I’m from the South of Newark, so it was a whole bunch of people that was SoSouth, it was the South versus everybody. It was the South movement and that was their shit.

Was your mom into music at all?

Bandmanrill: My mom loved music. She used to always be cleaning the house, listening to my father playing music or bumping music in her headphones.

Is there anything you remember her playing that stuck with you?

Bandmanrill: My mother used to play that Adele song. There’s this one song that she put me on, “Too Close” by Alex Clare. She be playing all kinds of shit. She mainly be playing house music and shit though.

I think that’s interesting because sometimes in your music there’ll be that slower sample in it, where you’ll add in that poppier sound. Do you do that to balance the music out?

Bandmanrill: Definitely to balance it out. It just depends on the vibe of the song. The best thing about Jersey club is that you can make it do whatever: make it sound real poppy, real clubby, or even a little more drilly. Jersey club, you can really make it sound like anything.

Were you listening to drill when you were growing up?

Bandmanrill: I was listening to Chicago drill like Chief Keef, L’A Capone, Shit like that. When New York came out with drill, Curly Savv, Bam Bino, 22Gz, Sheff G. That’s the drill that I was familiar with.

How about crunk music? Were you ever into that?

Bandmanrill: I don’t know about crunk music, but I know that’s Southern – I don’t want to say Southern because I don’t know where it originated, but I believe it was Memphis. That crunk shit is definitely similar to Jersey club music because that shit’s real uptempo and it’ll get you hype. I fuck with that shit for sure.

What was the reception like in Jersey when Drake hopped on a Jersey club beat?

Bandmanrill: Everyone was asking me, “Damn. Why aren’t you on there?” “N***a, I don’t know. Ask that n***a.” It is what it is. I salute Drake for getting on the wave. He put a lot of eyes on the movement.

Do you think it helped propel your music?

Bandmanrill: Yeah, it definitely did, slightly. Just because of the sound, getting more people familiar with the sound, getting people talking.

We’re in LA, you’ve rapped about Nipsey Hussle in your music, how has he resonated with you as a person?

Bandmanrill: I fuck with how he’s a leader. I like n****s that believe in their own shit and don’t follow behind nobody’s orders and just want to be rich and take over. When Nip got his money up and bought a store in that same complex that he was standing in front of, that’s inspiring. A lot of people in the hood got the mindset of getting that money, but a lot of people don’t have that mindset of what are you going to do after you get that money, what are you going to do for your kids? He thought about everything. He was a smart hood n***a.

What has boxing taught you?

Bandmanrill: Discipline. For example, I smoke a lot now – when I was boxing I wasn’t smoking – but if I want to stop smoking right now, I can. It taught me, mentally, you don’t really need nothing. Everything’s mental. As long as you’re strong enough, you’re good. Stay in good shape, you’ll be fine.

How have you applied that same discipline to rapping?

Bandmanrill: Just trying to stay in the stu. When I do something, I’m always going to put my 120% into it. When I was boxing, I was doing that shit 120%, waking up before school to go run at 4, go to school at 6 and go to the gym right after. It’s the same thing with rap: wake up early, probably write a song, go to the stu, make mad songs, and do the same thing everyday. Just being disciplined and staying focused.

Do you think that makes you a better rapper?

Bandmanrill: For sure. Practice makes perfect. Everything you keep doing, you’re always going to get better at it. My coach always used to tell me, “You don’t become a pro at something until you put your 10,000 hours into it.” I’ve got to do double that, 10x that, to become better than a pro.

Can you describe to me the first time you started rapping?

Bandmanrill: I started rapping in my house in my own studio. I was real comfortable. My only problem when I first started is that I was unsure if I was good because I ain’t know what good was. When I was hearing other people’s shit, I was like, “There’s no way that you can like this shit and not like my shit.” I just went off that.

How about when you first started rapping over Jersey club beats? When did that first happen?

Bandmanrill: That was my fifth or sixth song that I put out, ever. I was talking to my mans one day, and he was just like, “Yo, why nobody ever rap on a club beat before?” I was like, “Y’know, that’s a good question.” We’re from Jersey and I’m just sitting around thinking about it like, “You’re right.” I just did it, and to be real with you, I didn’t even finish the song. I just recorded 15 seconds of the song and put it on TikTok. When I put it on TikTok, it just blew up, and that’s when I went and finished the song.

Was the reception on TikTok different than the reception in Jersey?

Bandmanrill: Yeah, definitely. When it was first going off, the reception on TikTok was going so crazy, but the reception in Jersey was like, “Nah, this n***a rapping on club… He going off club…” A lot of n****s were haters.

Did the reception on TikTok push you to keep going?

Bandmanrill: It showed me that shit could happen. My whole life I’ve just been waiting on that one moment that showed me that shit could work. That was that moment.

With TikTok, did you have a following before you started rapping?

Bandmanrill: Yeah. I’m just a funny n***a. I used to make little funny videos that you would only really understand if you were from Newark or Jersey. When I built up my following, obviously my following would be just straight Newark and Jersey because that’s what I make content for. I just started making music and I was decent, so people was fucking with me.

You ride or die for Jersey. Do you think that sets you apart from a lot of other rappers?

Bandmanrill: I’m real thorough. I always stand up for where I’m from or what I believe in For Jersey, it’s about time that somebody steps up for Jersey because nobody’s done it. Jersey just needs a forefront. Everybody’s afraid to do it, but I’m not.

How did Club Godfather come into fruition?

Bandmanrill: Shit just locked in with my producer. I didn’t really lock in on the project. I go to the studio everyday for at least 6 to 12 hours. Over time, we just listened to all the songs like, “This the best song. This the best song. This the best song.” We just threw them all on a project that we felt had the best ones and that’s the project.

Do you think you’re always going to be rapping over club beats?

Bandmanrill: Probably, yeah. I want the industry to be rapping over club beats. You can put a club beat on anything, melodies or drill beats; you can put it on anything and it’s going to turn your beat into something totally different.

What do you want to accomplish in the next five years?

Bandmanrill: I want to be the biggest rapper in the world. Now, I’ve reached my goal of being the biggest rapper in Jersey, and it’s time to take over the world now. Everyone wants to be a rapper, but I want to be the rapper, the one that’s different than all the rest and made it further than everybody else. I feel like I got the opportunity to do that with my sound that I brought to the industry and getting everybody on there and showing love to where I’m from, Newark, Jersey and our culture.

What would make you feel like you’ve made it further than everyone else?

Bandmanrill: When everytime I drop an album, it goes #1 every time.

After people listen to Club Godfather, what do you want them to know about Bandmanrill?

Bandmanrill: That this is just volume one of this club genre and every tape after this is going to get better and better and better, just reinventing more club stuff. You might even hear some stuff that’s not club, just improving and getting better as an artist.

What was it like growing up with eleven brothers?

Bandmanrill: When I was young, I didn’t grow up with my eleven brothers. It was me, my mother, my father, my grandfather, my grandmother, my sister, my auntie, her son, her brother, and my uncle. As I got older, they started moving out and it was just me, my mother, my sister and her daughter, her n***a, and my father ended up leaving. I always had two or three brothers around. I always see the other ones here and there.

I heard they started the SoSouth movement.

Bandmanrill: It was a movement called SoSouth. My brother had a camera and shit; he used to be recording all the videos. I used to sneak into his room and look at all the videos. He used to have all the money and all the bitches and shit. When I was young, I always wanted to be like that; I always wanted to be a star. I didn’t necessarily know I wanted to be in rapping. The rapper lifestyle was always intriguing to me though.

So SoSouth was more of a musical movement?

Bandmanrill: I’m from the South of Newark, so it was a whole bunch of people that was SoSouth, it was the South versus everybody. It was the South movement and that was their shit.

Was your mom into music at all?

Bandmanrill: My mom loved music. She used to always be cleaning the house, listening to my father playing music or bumping music in her headphones.

Is there anything you remember her playing that stuck with you?

Bandmanrill: My mother used to play that Adele song. There’s this one song that she put me on, “Too Close” by Alex Clare. She be playing all kinds of shit. She mainly be playing house music and shit though.

I think that’s interesting because sometimes in your music there’ll be that slower sample in it, where you’ll add in that poppier sound. Do you do that to balance the music out?

Bandmanrill: Definitely to balance it out. It just depends on the vibe of the song. The best thing about Jersey club is that you can make it do whatever: make it sound real poppy, real clubby, or even a little more drilly. Jersey club, you can really make it sound like anything.

Were you listening to drill when you were growing up?

Bandmanrill: I was listening to Chicago drill like Chief Keef, L’A Capone, Shit like that. When New York came out with drill, Curly Savv, Bam Bino, 22Gz, Sheff G. That’s the drill that I was familiar with.

How about crunk music? Were you ever into that?

Bandmanrill: I don’t know about crunk music, but I know that’s Southern – I don’t want to say Southern because I don’t know where it originated, but I believe it was Memphis. That crunk shit is definitely similar to Jersey club music because that shit’s real uptempo and it’ll get you hype. I fuck with that shit for sure.

What was the reception like in Jersey when Drake hopped on a Jersey club beat?

Bandmanrill: Everyone was asking me, “Damn. Why aren’t you on there?” “N***a, I don’t know. Ask that n***a.” It is what it is. I salute Drake for getting on the wave. He put a lot of eyes on the movement.

Do you think it helped propel your music?

Bandmanrill: Yeah, it definitely did, slightly. Just because of the sound, getting more people familiar with the sound, getting people talking.

We’re in LA, you’ve rapped about Nipsey Hussle in your music, how has he resonated with you as a person?

Bandmanrill: I fuck with how he’s a leader. I like n****s that believe in their own shit and don’t follow behind nobody’s orders and just want to be rich and take over. When Nip got his money up and bought a store in that same complex that he was standing in front of, that’s inspiring. A lot of people in the hood got the mindset of getting that money, but a lot of people don’t have that mindset of what are you going to do after you get that money, what are you going to do for your kids? He thought about everything. He was a smart hood n***a.

What has boxing taught you?

Bandmanrill: Discipline. For example, I smoke a lot now – when I was boxing I wasn’t smoking – but if I want to stop smoking right now, I can. It taught me, mentally, you don’t really need nothing. Everything’s mental. As long as you’re strong enough, you’re good. Stay in good shape, you’ll be fine.

How have you applied that same discipline to rapping?

Bandmanrill: Just trying to stay in the stu. When I do something, I’m always going to put my 120% into it. When I was boxing, I was doing that shit 120%, waking up before school to go run at 4, go to school at 6 and go to the gym right after. It’s the same thing with rap: wake up early, probably write a song, go to the stu, make mad songs, and do the same thing everyday. Just being disciplined and staying focused.

Do you think that makes you a better rapper?

Bandmanrill: For sure. Practice makes perfect. Everything you keep doing, you’re always going to get better at it. My coach always used to tell me, “You don’t become a pro at something until you put your 10,000 hours into it.” I’ve got to do double that, 10x that, to become better than a pro.

Can you describe to me the first time you started rapping?

Bandmanrill: I started rapping in my house in my own studio. I was real comfortable. My only problem when I first started is that I was unsure if I was good because I ain’t know what good was. When I was hearing other people’s shit, I was like, “There’s no way that you can like this shit and not like my shit.” I just went off that.

How about when you first started rapping over Jersey club beats? When did that first happen?

Bandmanrill: That was my fifth or sixth song that I put out, ever. I was talking to my mans one day, and he was just like, “Yo, why nobody ever rap on a club beat before?” I was like, “Y’know, that’s a good question.” We’re from Jersey and I’m just sitting around thinking about it like, “You’re right.” I just did it, and to be real with you, I didn’t even finish the song. I just recorded 15 seconds of the song and put it on TikTok. When I put it on TikTok, it just blew up, and that’s when I went and finished the song.

Was the reception on TikTok different than the reception in Jersey?

Bandmanrill: Yeah, definitely. When it was first going off, the reception on TikTok was going so crazy, but the reception in Jersey was like, “Nah, this n***a rapping on club… He going off club…” A lot of n****s were haters.

Did the reception on TikTok push you to keep going?

Bandmanrill: It showed me that shit could happen. My whole life I’ve just been waiting on that one moment that showed me that shit could work. That was that moment.

With TikTok, did you have a following before you started rapping?

Bandmanrill: Yeah. I’m just a funny n***a. I used to make little funny videos that you would only really understand if you were from Newark or Jersey. When I built up my following, obviously my following would be just straight Newark and Jersey because that’s what I make content for. I just started making music and I was decent, so people was fucking with me.

You ride or die for Jersey. Do you think that sets you apart from a lot of other rappers?

Bandmanrill: I’m real thorough. I always stand up for where I’m from or what I believe in For Jersey, it’s about time that somebody steps up for Jersey because nobody’s done it. Jersey just needs a forefront. Everybody’s afraid to do it, but I’m not.

How did Club Godfather come into fruition?

Bandmanrill: Shit just locked in with my producer. I didn’t really lock in on the project. I go to the studio everyday for at least 6 to 12 hours. Over time, we just listened to all the songs like, “This the best song. This the best song. This the best song.” We just threw them all on a project that we felt had the best ones and that’s the project.

Do you think you’re always going to be rapping over club beats?

Bandmanrill: Probably, yeah. I want the industry to be rapping over club beats. You can put a club beat on anything, melodies or drill beats; you can put it on anything and it’s going to turn your beat into something totally different.

What do you want to accomplish in the next five years?

Bandmanrill: I want to be the biggest rapper in the world. Now, I’ve reached my goal of being the biggest rapper in Jersey, and it’s time to take over the world now. Everyone wants to be a rapper, but I want to be the rapper, the one that’s different than all the rest and made it further than everybody else. I feel like I got the opportunity to do that with my sound that I brought to the industry and getting everybody on there and showing love to where I’m from, Newark, Jersey and our culture.

What would make you feel like you’ve made it further than everyone else?

Bandmanrill: When everytime I drop an album, it goes #1 every time.

After people listen to Club Godfather, what do you want them to know about Bandmanrill?

Bandmanrill: That this is just volume one of this club genre and every tape after this is going to get better and better and better, just reinventing more club stuff. You might even hear some stuff that’s not club, just improving and getting better as an artist.

I heard they started the SoSouth movement.

Bandmanrill: It was a movement called SoSouth. My brother had a camera and shit; he used to be recording all the videos. I used to sneak into his room and look at all the videos. He used to have all the money and all the bitches and shit. When I was young, I always wanted to be like that; I always wanted to be a star. I didn’t necessarily know I wanted to be in rapping. The rapper lifestyle was always intriguing to me though.

So SoSouth was more of a musical movement?

Bandmanrill: I’m from the South of Newark, so it was a whole bunch of people that was SoSouth, it was the South versus everybody. It was the South movement and that was their shit.

Was your mom into music at all?

Bandmanrill: My mom loved music. She used to always be cleaning the house, listening to my father playing music or bumping music in her headphones.

Is there anything you remember her playing that stuck with you?

Bandmanrill: My mother used to play that Adele song. There’s this one song that she put me on, “Too Close” by Alex Clare. She be playing all kinds of shit. She mainly be playing house music and shit though.

I think that’s interesting because sometimes in your music there’ll be that slower sample in it, where you’ll add in that poppier sound. Do you do that to balance the music out?

Bandmanrill: Definitely to balance it out. It just depends on the vibe of the song. The best thing about Jersey club is that you can make it do whatever: make it sound real poppy, real clubby, or even a little more drilly. Jersey club, you can really make it sound like anything.

Were you listening to drill when you were growing up?

Bandmanrill: I was listening to Chicago drill like Chief Keef, L’A Capone, Shit like that. When New York came out with drill, Curly Savv, Bam Bino, 22Gz, Sheff G. That’s the drill that I was familiar with.

How about crunk music? Were you ever into that?

Bandmanrill: I don’t know about crunk music, but I know that’s Southern – I don’t want to say Southern because I don’t know where it originated, but I believe it was Memphis. That crunk shit is definitely similar to Jersey club music because that shit’s real uptempo and it’ll get you hype. I fuck with that shit for sure.

What was the reception like in Jersey when Drake hopped on a Jersey club beat?