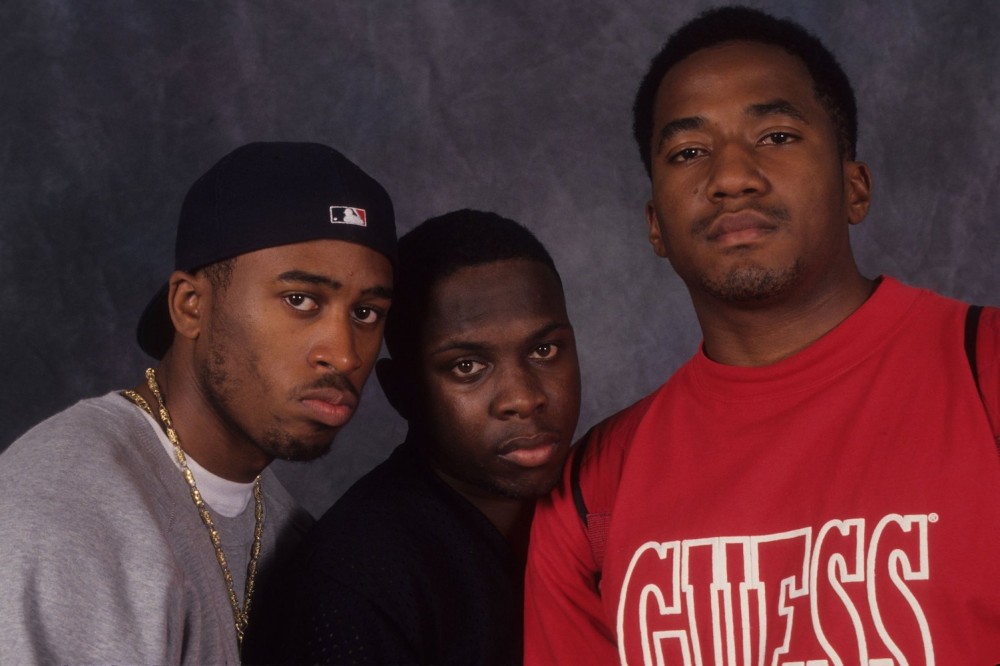

How a Portion of A Tribe Called Quest’s Royalties Became An NFT — And How the Group Plans on Getting it Back

A Tribe Called Quest is currently trying to retrieve a share of their sound recording royalties that was recently auctioned off as an NFT.

In late June, it was announced that an NFT made up of the sound recording royalties from the first five A Tribe Called Quest albums was being auctioned off. A report from Billboard stated that the NFT — derived from a 1.5% share of the group’s sound recording royalties — was being auctioned off by online music royalties marketplace Royalty Exchange. A day later, the NFT had been sold for almost $85,000.

Because of how the news was presented, it seemed as if the beloved hip-hop group was involved in the process. This turned out not to be the case. Co-founding member Ali Shaheed Muhammad addressed the NFT sale in a lengthy Facebook post. He shared how Ed Chalpin — the owner of music company PPX Enterprises — had added an unfair clause in their agreement deal with Jive Records when they signed to the label. The clause added was that Chalpin and entertainment attorney Ron Skoler would “get paid a percentage of our recording fund EVERY time we commenced to record a new album,” according to Muhammad’s post. According to a 1992 article from Billboard, Chalpin was supposed to receive “15% of the group’s earnings for the term of its recording contract at Zomba/Jive in return for Chalpin having negotiated the contract.”

At this point, Chalpin and Skoler had been longtime associates. According to Skoler’s own website, after he graduated from law school and was admitted to the bar, he accepted an in-house attorney position with Chalpin’s PPX. The two then became business partners and founded the company Rhythm Method Enterprises — alongside Chuck D and Keith Shocklee — where they signed artists like DJ Red Alert, The Jungle Brothers, and others. If you read through Skoler’s website, A Tribe Called Quest is also listed as an artist once signed to Rhythm Method. But according to Muhammad, Chalpin and Skoler should’ve never represented the group.

He explained how Skoler was the attorney for DJ Red Alert and that Tribe was signed to a production deal under Alert’s Red Alert Productions — the DJ’s own management and production company — that was signed to Jive Records. (Red Alert was also Tribe’s manager during this time.)

“Those guys should have never been negotiating this deal but because it was a quote, unquote production deal to Red Alert Productions, technically they were representing Red Alert and not A Tribe Called Quest,” Muhammad told Okayplayer during a phone conversation.

Muhammad, who is the co-founder of the Jazz Is Dead label, then said the group didn’t learn of this clause until they began recording their second album, The Low End Theory. They disputed the clause; Chalpin sued them and lost but appealed the case. Already in debt to Jive but not wanting to be taken advantage of by Chalpin, the group managed to get Jive’s help in litigating the costs against Chalpin’s appeal by agreeing to make a sixth album with the label.

That same 1992 Billboard article detailed the outcome of the settlement: that, along with a $37,500 receipt the group had already paid Chalpin, he was also to be awarded $44,932.13, “essentially 15% of all monies already advanced or paid to the act by Zomba.”

“The agreement spans Tribe’s first five albums, for which Chalpin is guaranteed at least $150,000. In addition to that commission, Zomba must pay Chalpin $60,000,” the report added.

Despite Chalpin passing in 2019, his questionable practices have come back to haunt the group. Muhammad explained that the settlement reached between Chalpin and Jive involved a share of their music. That share was then sold to an individual who entered into a partnership with Royalty Exchange, leading to the creation of the NFT that was then sold last month.

Amid Muhammad — and Q-Tip — speaking out against the NFT, Royalty Exchange CEO Anthony Martini told Pitchfork that he had reached out to members of the group “and had positive conversations clearing up any confusion.” In an interview with Music Business Worldwide, Martini addressed the topic again, clarifying that Royalty Exchange didn’t do a deal directly with A Tribe Called Quest, and that he had spoken specifically with Muhammad about it all.

Muhammad confirmed that he had in fact spoken with Martini, and that their conversation had been productive.

“[Anthony] unknowingly entered into an agreement with this person who purchased this asset who also unknowingly purchased it not knowing that, basically, A Tribe Called Quest was hustled for that percentage,” Muhammad said. “So there was no fault with Royalty Exchange.”

Muhammad also shared that Q-Tip had a fruitful conversation with the person who purchased the asset from PPX, adding that he’s not only a fan of the group but is also involved in the music business as a publisher. (Muhammad said he hasn’t yet spoken with the actual bidder who won the auction.)

“When he learned that the person he purchased this percentage from acquired it in a less than favorable way, he was really touched by that and did not like that,” Muhammad said. “We’re really hoping that at the end…the asset will come back home to the members of A Tribe Called Quest.”

Although Muhammad sounded hopeful about the prospect of the group retrieving this share, there’s still some questions that need answers. Specifically — did Jive give Chalpin a percentage of their ownership or a percentage of A Tribe Called Quest’s ownership as a part of their settlement? That the group is dealing with this problem that stems from an agreement they signed in their late teens, speaks to how nefarious and unfair the music industry has been and continues to be, especially toward Black artists. It’s hard not to think of Q-Tip’s infamous warning of suspicious industry figures on “Check The Rhime” — “Industry rule #4080, record company people are shady” — and how the almost 30-year-old sentiment still resonates to this day.

“It is twofold,” Muhammad said of seeing the sentiment still being prevalent today. “It’s a reminder — watch your back…but then it makes you go, ‘OK, the work is not done and the struggle continues, so what do we do with the time [while] we’re here?’”

What has happened with the Tribe NFT is likely not going to be the only instance. NFTs are still a relatively new phenomenon and although not all NFTs will lead to fortune for its sellers, the Tribe NFT may encourage others with their own shares to sell them for a quick buck — whether they were involved in a piece of music’s creation or not. Still, Muhammad sees the benefit of NFTs from an artist standpoint, and not having to consult a middleman to get their work to a fan that wants it.

“I’m not in support of a record company whose old deal they would use to give them authority in the new space,” he said. “I am hopeful that it is a space… to use the NFT medium as a means to be in a better place with the assets financially.”