Nate LeBlanc‘s scratches are so ill, you should call him the Tiger King.

On a quiet street in Los Angeles, you’ll find a chemistry lab in a former horse stable behind a nondescript stucco home. Upon first glance, it seems unlikely that deeply funky, heartfelt hip-hop is conceived behind the walls. However, this ranch-style dwelling, bigger than it seems from the outside, belongs to the storied turntablist and producer, Cut Chemist.

The hip-hop instrumentalist, Jurassic 5 producer, and Ozomatli DJ is an analog-minded artist who expresses himself through inimitable creative pastiche. After several hours of phone interviews, we finally met face to face last winter. He received my visit warmly, if a bit warily, leading me through the dark house, curtains drawn against a fading winter sun, before finally stopping in the “lab,” the converted stable where a portion of his legendary record collection looms behind his turntables.

Understandably tired, the artist born Lucas McFadden had just returned from an out-of-town gig not long before the pandemic began. His face carried a few days stubble; his eyes were kind but slightly heavy. He clearly had a lot on his mind. He was dressed casually in a guayabera-style button up and lived-in Levi’s. His Adidas Superstars and backwards cap spoke to a life spent in hip-hop, the vernacular of b-boy culture still informing his sensibilities. On the walls there are signed gig posters; in the corner, a life-size R2D2 model. Of course, there are shelves of records. The past is ever-present in Cut’s life: a source to draw from whether it’s through sampling, artwork, creative inspiration, or simply the strength to move forward in life amidst emotional turbulence.

After a quarter century of successful collaborations, Cut Chemist has shifted his primary focus to his solo career. He funded and released his latest, the ambitious Die Cut himself, building it from previously-untapped sample sources and musical inspirations — in search of a unique sound to express his state of mind. It has been a rough couple of years, as he’s struggled with personal and familial issues, not always sure of the best path forward. This legendary DJ is on his own, exploring the outer limits of sample-based music, fusing elements from disparate cultures and eras. Selling that vision and ensuring that the story was told properly, would prove to be somewhat more challenging.

Cut Chemist is a storyteller. As an art student, he sketched on his class notes, incorporating comic book and graffiti styles, quoting and repurposing compelling images. In his work as a world-renowned DJ, producer, and recording artist, he has a unique gift for weaving disparate sources together into a narrative that no one else would imagine. Die Cut is truly autobiographical, meant to sum up a life steeped in music from the very beginning.

He was raised in Hollywood, in a house that his father purchased sight-unseen after being assured that it was on the right side of Franklin Boulevard. The house was filled with music.

“There was a baby grand piano in the living room,” Cut recalled. “My mom played and my dad wrote poetry and music. They were making friends with musicians… The very first thing that I remember remembering is a drum set in the house and I was fascinated by it.”

He was exposed to a wide variety of music from family friend and occasional babysitter David Winans II, a member of the famous Winans family band. As he grew older, Cut began to collect records and began making music, the passions that would define his adult life.

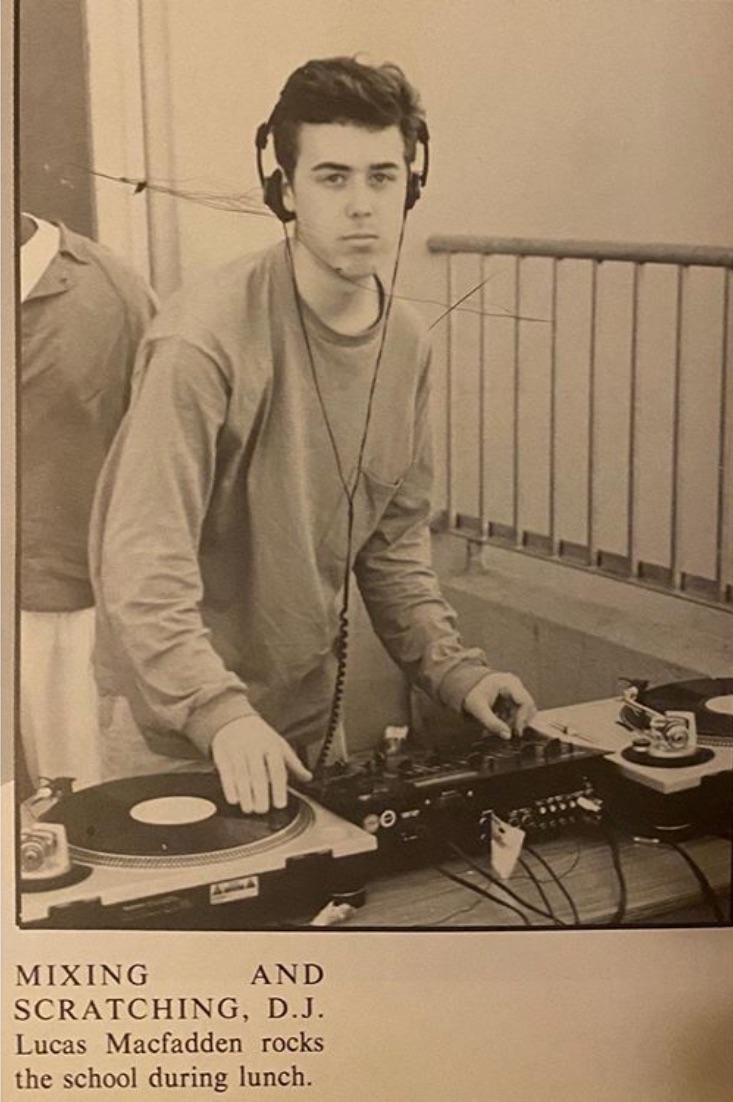

Young DJ Mystro sometime before choosing from between two potential handles, Cut Chemist and Cut Librarian

The DJ prodigy battled full grown adults at the Breakers Only store on Hollywood & Vine on his 12th birthday. Eventually, he began to amass a collection; first, he focused on the hits of the day, then branched out into foundational east coast hip-hop, and finally breaks and samples traced back to the root. His childhood friend Marvin “Marvski” Fowler was an early influence:

“Marvski was the first dude that I could really build with about old records, breakbeats,” Cut says. “I remember him telling me ‘man, every dope beat is James Brown.”

As a teenager, he formed a group called Unity Committee and tirelessly pursued a recording contract for them, hustling demos and nearly landing them a deal. Their goal was modest: contributing to hip-hop culture, and being able to stand shoulder to shoulder with the east coast groups that inspired them. Forget fame or fancy cars; they wanted to be the next Jungle Brothers. By now a highly skilled DJ/Producer and crate-digger, Cut spent most of his time searching for new records that yielded ear-catching passages for loop tapes. Pairing these beat sketches with breaks and bass lines, it proved a stark contrast from the electro-rap 808 workouts that LA was then known for.

What also helped Unity Committee stand apart two MCs with winning chemistry and distinct voices. Chali 2na possessed an upright bass disguised as a vocal cord, and was a notebook-filling writer who refused to merely lean into this vocal range as a gimmick. Marc 7 had a raspier instrument in a higher register and brought a wise, everyman persona to the group.

“We were in talks with Jive, and it was looking pretty good,” Cut Chemist says. “Then all of a sudden it went away because this group called Digital Underground had come out. “[They] were really similar to Unity Committee. They used some similar samples, Shock G had a very Charli 2na vibe; Money B had a very Marc 7 vibe, DJ Fuze had a very Cut Chemist vibe. In fact a lot of people confused me with him.”

Unity Committee regularly performed around LA at college parties and The Good Life, the health food store-turned-open mic tabernacle that served as the launching pad for the most creative performers of the era.

They frequently rolled with their friends and compatriots in Darkleaf, which comprised Cut’s childhood friend Hymnal and other MCs who favored abstract rhymes and a mystical aesthetic. Another boisterous rhymer with a terrifically loud voice named Double D, soon to be rechristened Volume 10, was often by their side. At the Good Life, Cut soon took notice of a group that eschewed the local style of intricate multisyllabic rhyme schemes known as “the chop” for a throwback, sing-song group harmony sound reminiscent of rap’s earliest days.

Akil, Zakir, and DJ Nu-Mark were known as the Rebels of Rhythm. As a dedicated student of park jam era hip-hop with a healthy collection of dubbed cassettes of Treacherous 3 and Cold Crush Brothers routines, Cut immediately understood what they were doing. Eventually, the two groups would merge into a single unit called Jurassic 5. The six-man crew with two world-class DJs, a singsong style of hooks and four everyman MCs would help propel independent hip-hop onto the charts and infuse good vibes into the dour, competitive underground hip-hop scene.

“I was so inspired by De La Soul’s third album [Buhloone Mind State], ”Cut says. “I went home and made a beat in 5 minutes, that ended up being Unified Rebellion. I thought those Rebels of Rhythm from The Good Life would sound good on it, boom- Jurassic 5 was born.”

Inspired by the explosive local reaction to the independent vinyl release of Freestyle Fellowship’s …To Whom It May Concern, Jurassic 5 decided to press their own record. Cut put his cut-and-paste ode to Double Dee and Steinski “Lesson 4: The Radio” on the B-side of “Unified Rebelution.” That sunny, intricately-produced throwback rap track announced J5 as one of the leading voices of a new era of underground West Coast hip-hop. They pressed 300 copies, and Cut sold them out of the trunk of his Honda.

“We were a west coast group, catering to old-school east coast hip-hop sounds,” Cut Chemist recalls. “We joined the independent record movement in ‘95, put out our own record and said forget shopping shit around to labels, that ain’t working.”

Eventually, Blunt Records in New York signed them for a single deal and the record was embraced by the burgeoning east coast Fat Beats rap scene. For Cut Chemist, a lifelong Angeleno, hearing his record played by Funkmaster Flex on Hot 97 was a heady form of validation. His dreams were beginning to come true.

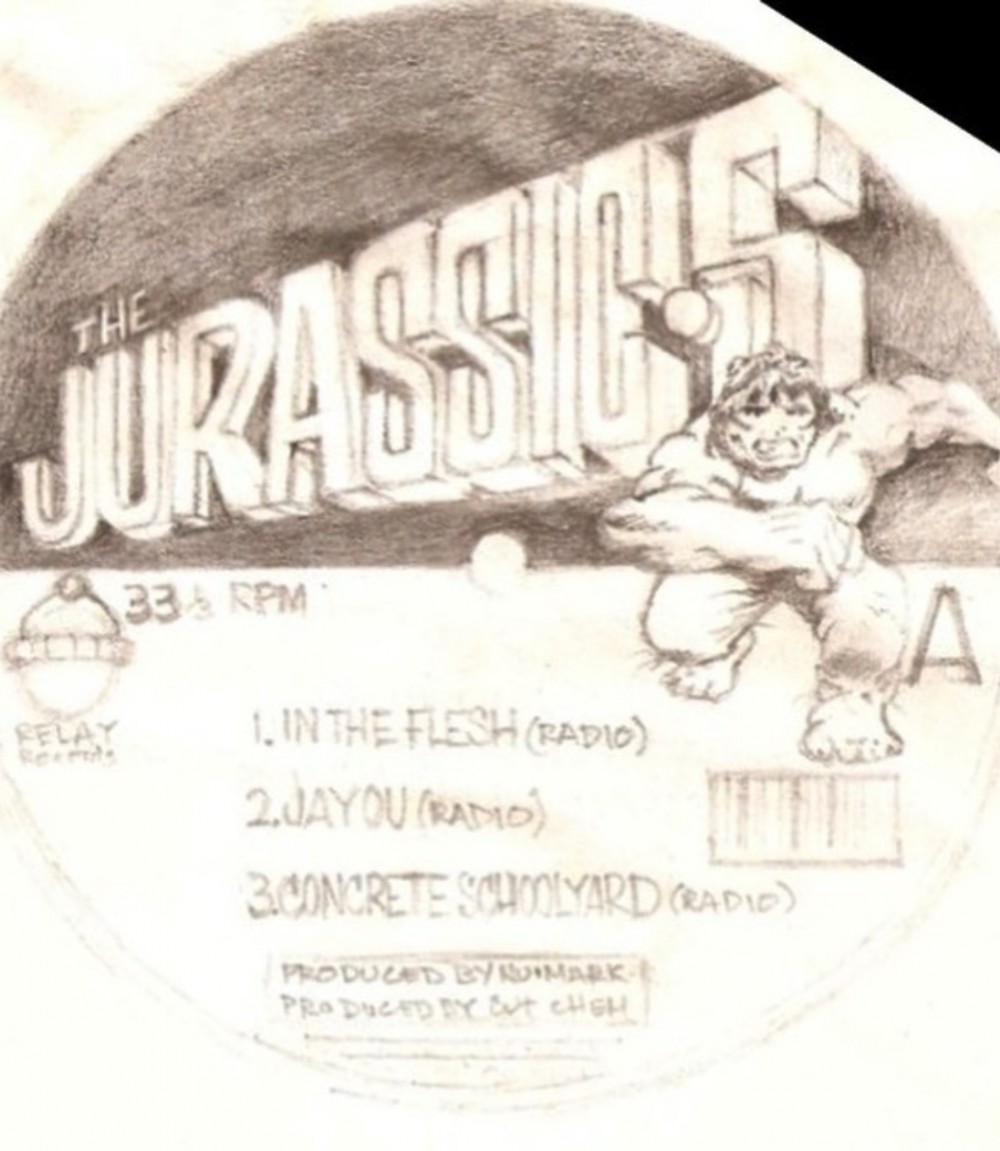

Cut Chemist’s original pencil sketch for the Jurassic 5 EP label

While enrolled at UCLA, Cut often worked on papers and songs simultaneously in the studio, doodling covers and logos for music projects in the margins of his class notes.

“I always had it burned in my brain that finishing college was important to have something to fall back on,” Cut Chemist says. “I never thought I could use music as a way to make a living. It was a hobby.” But it turned out to be much more as he rode the wave of the independent hip-hop scene to a thriving music career.

In the late 90’s, San Francisco-based promoter Mark Herlihy, the producer of the DJ showcase series Future Primitive Soundsession had the idea to pair Cut and DJ Shadow for a collaborative project. The two DJs shared omnivorous record collecting habits, excellent technical skills, and formed the backbone for independent rap crews. They had both made tracks called “Lesson 4” that were part sequel and part homage to Double Dee and Steinski’s classic cut-up Lesson series.

Their bond deepened after the first of many record digging trips. Somewhere outside of Oklahoma City, Cut gave Shadow a copy of his mixtape Rare Equations. “He called me later in the week and said, ‘I love the blend you do with “Humpin’” by the Bar-Kays and the Meters’ “Funky Miracle,’ Cut Chemist recalled fondly, decades later. “You knew that he was getting all of the little nuances.”

An impressed Shadow asked his new friend to remix a song slated to appear on his debut album. Shadow’s original version of “The Number Song” is a technical marvel, moving and changing with exquisitely sourced breaks and a foreboding main sample that’s of a piece with the dour, rain-drenched vibe of Endtroducing. Cut’s remix keeps those elements but makes it more fun; he brings in a more organic intro and scratched hooks that turn the rainy day vibes into a house party. The tempo switch-ups keep the ear engaged, telling a well-rounded story with even more rare breakbeats. Defined by Shadow’s deep crates and Cut’s showmanship, the dynamic formed the basis of a series of collaborative mixes that would pushed DJ culture forward. Until then, there had been an intensive focus on strict technical ability, typified by ITF-style battle routines. Cut and Shadow’s mixes were comparatively more musical, using deep cuts rather than breaks and upping the ante for showmanship with high-wire 4-turntable theatrics that even a layman could appreciate.

“If I were to have a superpower, what I’d want and hope that I achieve is translating my personality through music,” Cut Chemist says. “That song sounds like who I am in everyday life.”

Early group photo of Jurassic 5 on the steps of Cut Chemist’s childhood home

Back in L.A., Jurassic 5 were finishing recording their self-titled EP at Cut Chemist’s mom’s house, a comfort zone that everyone had used as a home base from high school onward. The EP was a breath of fresh air: brashly nostalgic independent hip-hop that harkened back to the park jam era with harmonized hooks and exquisitely sampled beats. The denim-patterned sleeve with its instant-classic J5 logo stood apart from the dense, grafitti-inspired, minimalist underground rap aesthetic then in vogue. Jurassic 5 felt like a group you could get to know.

The group’s energetic, well-rehearsed live show was similarly refreshing. Both DJs were an active part of the presentation: Cut would scratch and re-mix the songs live; Nu-Mark would punctuate segments with toy instruments and quirky choices, such as replaying the underground era-defining “Tried By 12” melody on a mic’d up thumb piano. The entire band would play the “Concrete Schoolyard” bridge on kazoos. It was completely unlike the stage presence of their affiliated acts, emphasizing nostalgia and showmanship with a twinge of whimsy.

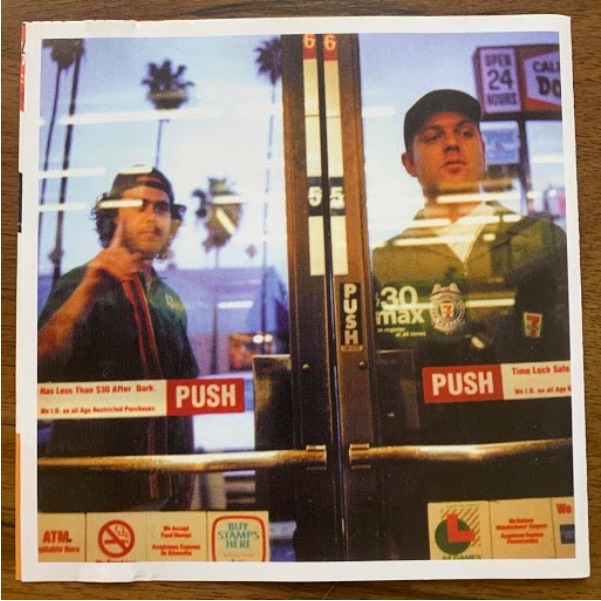

The late 90’s were a heady time for Cut Chemist. His career simultaneously expanded in two directions. Jurassic 5 began to attract major label attention, and his star rose as one of the most creative turntablist DJs in an increasingly popular scene. Brainfreeze began as a single show for Future Primitive, a funk 45 set by DJ Shadow and Cut Chemist unlike any other ever heard. The two DJs went back and forth on four turntables, using obscure but funky novelty records, and layered, scratched, juggled, and combined them in intriguing ways. The legend was spread by a hard-to-find CD pressing of the final practice session before the show. As a goof, they went down to the local 7-Eleven in Hollywood where Cut had played video games as a kid, asked if they could borrow spare clerk’s uniforms for a minute, and had photographer B+ take a few shots. Just as much as the irreverent selections of the mix itself, the cover helped the world see a different side of DJ Shadow — whose brooding countenance was rarely seen in his own album art.

Brainfreeze brought Cut Chemist renown outside of J5 too. His signature style of telling a story with other people’s records became suddenly in demand; his tasteful scratching and favorite breaks began generating an unprecedented amount of discussion in the early days of message board culture. An unintended consequence of the mix’s success was that the records they played instantly became sweated by voracious collectors, driving up the prices. A glance at eBay listings for funk records often includes the search term “Brainfreeze” to this day, often misattributed, but nonetheless speaking to the impact of the mix on the relatively small but deep break collecting community.

DJ Shadow & Cut Chemist- Brainfeeze (interior cover, photo by B+)

For all of the acclaim of their first collaboration, both Cut and DJ Shadow regard the follow-up mix, Product Placement, to be the superior body of work — mainly because it was intended as a recording and not a practice session for a live show. They continued with the same theme of basing the mix on promotional 45s for products, with an especially funky jingle for milk as the project’s centerpiece. It’s also a literal sequel, the second section consists of alternate versions of songs they had used on Brainfreeze, a winking flex of the depth of their crates. Where Brainfreeze focused more on funk music, especially the hard-hitting drums of Eddie Bo’s productions, Product Placement is more intentional about including several different strands of soul music and digging deeper for impossibly funky product promo 45s. As with Cut’s other work, it looks backward to the ‘60s and ‘70s for sources, but uses advanced techniques to bring it all together. From trick mixing, to scratching, to blending, the technical prowess on four turntables is astonishing.

When we spoke on the phone a few summers back, I had asked Cut if he enjoyed touring. “Only at the beginning,” he said. “We toured a lot.” Eventually the cramped quarters and grind of travel began to wear on him. The main benefit of touring came when promoters would carve out time for Cut to look for records. In our meeting in his home studio, there was a prominent pile of early hip-hop posters and handbills on the coffee table between us. In recent years he has turned his collecting focus more toward “paper,” the physical ephemera that marks important dates and times in the genre’s history. He is currently working on sourcing flyers for the earliest hip-hop shows. These essential documents were often hand-written on index cards of scrap paper, and are in danger of disappearing completely if not archived by scholars like Cut Chemist.

Touring Product Placement took Cut away from Jurassic 5 at a critical time: the recording of their third album, Power in Numbers. Whereas the EP and many parts of its follow-up Quality Control LP had been recorded at Cut’s mom’s house, the group wanted to try something different for the next project. Now signed to Interscope, they could have availed themselves of any recording studio they chose, but in order to keep costs down they decamped to DJ Nu-Mark’s house in the Valley, where he had put together a professional-level home studio. Working on a bulk of the songs while Cut was on the road, the group crafted a tighter, less playful body of work. When he returned home and listened to what was being put together, he was a bit surprised at the shape the record was taking. He remembers: “Wow, short verses, tight, no bullshit, this is kind of a different style of J5 that I didn’t see coming, but I liked it.” And once back in LA, he made significant contributions to the album.

Cut is extremely proud of his production and arrangement for “Thin Line,” a collaboration with singer Nelly Furtado.

“‘Thin Line’ was a big song for me, and it kind of changed everything,” he says. “It was the first song that I produced with a singer on it, so I looked at what I wanted to do with my production more as songwriting… I remember spending a long time on the harmony and really falling in love with the process of creating a song with not just rapping but singing and melodies and how I could possibly make hits one day.”

It led him to want to explore other parts of his musicality. Interscope’s decision to release the song as a single with R&B singer Mya on lead vocals, rather than his preferred original version also left a bit of a sour taste — a reminder of the politics that had begun to cloud the atmosphere around the group. Little things started to add up, and he realized that the time was right to leave the group and fulfill his lifelong dream of crafting a solo project.

Before he and Shadow launched their collaborative mix series, Cut Chemist had nearly signed to Mo’ Wax. The once upstart home for forward-thinking instrumental hip-hop had released not just Shadow, but also the outlandishly macabre Dr. Octagon, and the urbane hotel lobby music of UK natives Attica Blues. Mo’ Wax founder James Lavelle was interested in inking Cut Chemist to an album deal after a series of successful remixes for the label. However, the deal never came to fruition. One can imagine an alternate reality in which Cut released a solo instrumental hip-hop album at the time, perhaps the kind of record like Shadow’s Endtroducing, that elicited nods of approval from stoned Englishmen in anoraks.

Outtake for The Audience’s Listening cover shoot

It took a few years and many globe-trotting adventures, but eventually Cut Chemist signed with Warner Bros. in 2002. Four years later, he released his solo debut The Audience’s Listening — which immediately became the purest distillation of his sound. It combined a love for Brazillian music, his take on the talking-turntable stylings of Kid Koala, a refresh of the big beat ethos of Fatboy Slim, and many more ideas.

The album’s two singles demonstrate how Cut drew from different sections of his record collection to form the basis for his creations. “What’s The Altitude” is a charming slice of dance-rap with vocals from Cut’s childhood friend Hymnal inspired by their love of 90’s indie rock. The propulsive track was a minor hit, garnering radio play and added to numerous compilations and soundtracks.

Over time, the biggest hit from Audience was “The Garden,” Cut Chemist’s ode to the Brazilian music that he studied in college. He is still a bit stung by criticism that the primary vocal sample, from well-known Brazilian chanteuse Astrud Gilberto, was not obscure enough. He has been told numerous times over the years that using the vocals of the popular chanteuse is somehow unbecoming for a renowned digger such as himself. The irony, of course, is that the sample exists alongside many others that most people don’t recognize, that the only reason they are calling it out is because it’s so familiar. The fact is that he made many versions of the song with various vocals and the Gilberto version was the best of the bunch. This back-and-forth says a lot about the somewhat macho culture of one-upmanship that exists in the DJ world, where knowledge is power and obscurity is street cred — ignoring the fact that some of the greatest hip-hop songs in the world are made from recognizable samples.

In retrospect, Cut realizes that even though the process of making it was somewhat grueling, he is struck by how fun the project still sounds.

“It sounds like a kid who’s just having fun with a bunch of records and a bunch of music and that’s exactly what I wanted it to sound like,” he says. “It has a lot of the playfulness that was established in my J5 work but it’s also a step forward for me in terms of scratching better than anything I had done before. It had to sound like I was on a roller coaster ride rather than that I was tearing my hair out because it’s my first solo record and it’s on a major label. I think I achieved that.”

A dozen years is a long time between albums for any act, and the gap between The Audience is Listening and Die Cut was a veritable lifetime for Cut Chemist. After almost a decade apart, he reunited with Jurassic 5, they played Coachella and had a reunion tour. He and Shadow debuted their third collaborative The Hard Sell, a kind of last stand for analog audio that found the duo manning multiple decks and wearing turntables as guitars to battle anthropomorphized iPods. The world began to think of music as something that was to be stolen or streamed, as mostly worthless, as just another kind of file.

Most importantly, for undisclosed reasons, his moms house had left the family. That house, the home of his first studio Red October Chemical Storage Facility, an enclosed porch just off the dining room turned home studio, the clubhouse where Unity Committee was formed and the place where he found the limits of the volume tolerance of his extremely open minded and supportive parents recording demos, was gone. For Cut Chemist, the loss served as a mental pivot. That house was not just a house, it was a venue of support by his parents and friends. An almost commune type focal point of artistic energy for groups, collaborations and even solo projects. That support and open minded thinking has now carried on to the next venue, The Stable.

Die Cut was his first album made in the Stable era and it’s a more melancholy project than much of Chemist’s work. The sonic backbone came from an unlikely source; Cut had discovered the music of French proto-industrial bands Vox Populi! and their label-mates Pacific 231 while on tour in Europe. He was immediately drawn to what he described as their “psychedelic-electro-italo-disco-sample-based” music, that was unlike anything he’d ever heard. He struck a deal with the bands to curate and release a compilation of their material. He also began to build tracks for Die Cut from samples of their songs. Cut notes that it was “a new version of psychedelic, it wasn’t psychedelic rock in the sense that we know about from the 60’s. I was more of an 80’s psychedelic” less based on guitar exploration and more on tape loops heavily influenced by musique concrete, which made music out of environmental sounds.

That distinct industrial sample source palette is evident on the excellent album-opening track “Metalstorm.” That song features bar-trading MCs Edan and Mr Lif and stands as the most straightforward hip-hop song on the record. An acoustic folk song, “Plain Jane,” is inspired by his dad’s love of Bob Dylan. On that song Cut stepped out from behind the turntables. He plays acoustic guitar and even sings a shimmering background vocal. He also pairs the loose-limbed polyrhythmic drummer Deantoni Parks with the legendary MC Myka 9 who conjures unimaginable clusters of syllables. On the precious ballad “Home,” there are exploratory psychedelic wanderings with Laura Darlington. These disparate elements add up to create an audio autobiography. As a DJ and collector, Cut Chemist wanted the album to sound like his wide ranging listening habits.

“I have a lot of things that I want to get off my chest, a lot of things I need to sort out emotionally and intellectually,” he says. “And that comes out in music and art.”

Once the tracks were finished, Cut spent several years sequencing the album, an unusually long time even considering the amount of tinkering and perfecting that he put into crafting his debut years before. Die Cut is a chronicle of a difficult period in his life, one filled with personal and family-related struggles, and he wasn’t quite ready to let it go until he had sought out opinions from close friends and collaborators. Eventually he found a form that he was happy with and released the project on his own label, A Stable Sound.

Cut’s close friend and collaborator DJ Shadow described the relationship between the jaunty The Audience Is Listening and the comparatively morose Die Cut as being very different: “Not only because they’re from such different eras, but knowing him as well as I do, also knowing that he was in such different mind states when he made them. But I think what ties them together is just a desire to be heard on his own terms.”

Throughout our extensive conversations, there seemed to be a somber thread running through Cut Chemist’s comments. He has a wry sense of humor, and would light up when talking about records or early hip-hop flyers. But there seemed to be something more just below the surface, and it emerged as we discussed the challenges that he’s had getting Die Cut noticed in the sea of available digital releases. He wondered aloud why tracks weren’t landing on influential playlists, why the streaming numbers felt low, trying to make sense of how to market himself in this new landscape. Essentially, he feels like an analog person in a digital world.

“I don’t even get social media,” he says. “I belong to a world when it was physical — you sell a person a product through an outlet, I know how to do that. I know how many should be made, how long it’s going to take to sell, who the right person is to distribute it, all that stuff.”

He contrasts that with his view of the digital world: “It keeps changing… I can’t keep up with these kids, they’re just crazy with the technology, and every time I turn my head they’ve got a new trick up their sleeve, and they’re on top of it, and I’m not. But that’s okay, that’s the way it is.”

Nonetheless, Cut Chemist has had a legendary career. He quickly rose to underground prominence as an independent artist. He was embraced at a few different points by major labels. He has toured the world several times over. He’s an all-time great DJ, deeply respected for his abilities as a selector and a technician. He has fused the music of many cultures into acclaimed projects that reflect the melting pot of culture of his beloved life long home of Los Angeles. He was at ease as part of successful groups Jurassic 5 and Ozomatli but he pushed himself well beyond his comfort zone to pursue a hit-making solo career. He is intensely intentional about his releases, he invests a lot of himself each time, sculpting samples, stacking rhythms to tell stories with mostly instrumental music.

This ruminative craftsmanship is admirable but somewhat confounding. It’s unclear, even after extensive investigation, what exactly is gnawing at him, why birthing these albums seems almost torturous for him. Perhaps that is what makes him a great artist. He simply feels his way through the process. He compiles not just sounds but a wide array of feelings, into the music. He digs a level deeper than your standard beat maker or turntablist. Die Cut doesn’t sound like the record store’s sales floor, it sounds like the record store’s basement, the oddities that no one wanted reanimated and brought to life.

As our conversation wound down, Cut led me out the side gate of his house. Evening was quickly turning to night. He acknowledged that the pace of the previous period in his life was taking a toll on him, that he was physically and spiritually drained by the state of the world and the complications in his life, in a way that perhaps ran counter to his easy going public persona. The night before he had been playing to thousands of adoring fans at a raucous New Year’s Eve party. He is one of the foremost party rockers in the hip-hop industry, incredibly skilled at working with texture and tempo and unexpected selections, always grounded in absolutely knocking percussion. He’s a real craftsman, highly skilled in pushing people to dance, reacting physically to the propulsive, layered beats. And now mere hours later, he was a regular guy, at home after a long trip, among his admirable collectables and souvenirs gathered through a tremendous career, and he was profoundly tired. Tired enough for a stranger to remark on it. “I think,” he said, “you just met me at a really difficult time in my life.”

Die Cut has recently been reissued as a 2LP set including the album’s instrumentals. This record and more Cut Chemist merch and recordings from his life in music can be found at https://cutchemist.bandcamp.com/a-stable-sound-club