Abe Beame can’t believe you watched Dune on your iPad.

In the first of three “feature” vignettes in Wes Anderson’s elegiac, masterful French Dispatch, Benicio Del Toro, playing a frustrated incarcerated artist, voluntarily shackles himself to an electric chair. If you close your eyes and imagine an electric chair, you can see it. It’s an electric chair in a Museum of Natural History miniature, the barley twisted supports, the cable wired tin hat, the thick leather belt, the manacles, the cuffs locking his wrists to the chair’s arms.

He’s requested that his lover, and jailor, played by the great Lea Seydoux, throws the switch, sentencing himself to a premature death. When she asks why, he responds that he’s out of ideas, that he has no clue where to go next in his creative life, and he’s lost the will to live. She briefly throws the switch she pulls to jolt him back to life, and he recants, sees his impetuous foolishness for what it is. And this is the point of the film: Wes Anderson’s meticulous, stylized approach to mid 20th century Europe, applied to the idea of the dying self, and dying worlds, and fighting against that dying of the light.

Anderson’s film, shot with a perforated print filter, is pretty loyally based on the “vibe” of The New Yorker as the bastion of what journalism at its best can be, and the dream of Europe, of the escape to a better, more metropolitan and intellectualized world, a world populated by men and women who wear blazers and tiny round spectacles to a three martini lunch, who exceed their word count by five figures, who burst at the seams with curiosity that exists not to forward a career or make a name, but to scratch an itch, supported by a fatherly editor without concern for advertising space or page limit, who lives to support the art, back when it was one. In other words, it’s a prep school, dandefied, J.D. Salinger tinted lens that has always owed a debt to New Yorker curation.

I’ve seen critics largely mischaracterize The French Dispatch as a typically indulgent Anderson confection, a mood piece without focus that is an exercise in flex, but this is way off. It follows in the footsteps of his masterpiece, The Grand Budapest Hotel, a film that mines a specific time and place in the past to deliver a mature, intensely personal mission statement. It stands perhaps a head shorter than that movie because it lacks the show stopping, grounding, career fulcrum at its center that Ralph Fiennes lent it, but is shoulder to shoulder as a top five work that demands subsequent rewatches and contextualizations.

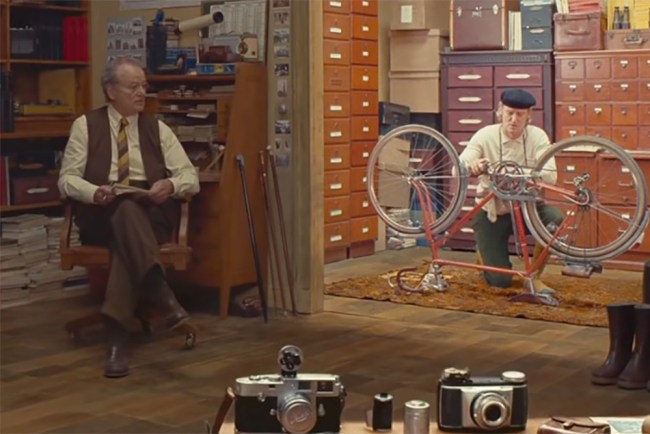

The French Dispatch is overseen by the paternal deity of the Anderson extended universe, Bill Murray, as the editor, Arthur Howitzer Jr., a dynastic publishing scion who baits his family into sending him overseas, where he remakes the titular publication into an institution. Howitzer Jr. lives in an antiquated world of publishing. He overpays for work. He loves, nourishes and supports his reporters because he loves writing and what is perceived even then, as the dying art of journalism. Like Owen Wilson handing in an irreverent, “charming” slice of life impressionistic portrait of a fleeting time and place from his bike saddle, or Frances McDormand grappling with an emergent generation of Tiktok Marxist revolutionaries. Like Ralph Fiennes’ Monsieur Gustave H. in Grand Budapest, he’s the ghost of an art that perhaps never existed, but Anderson is willing into existence in his obsessively detailed and lovingly manicured past. Howitzer Jr.’s death, the death of the paper, and the death of everything the editor and his writers represent, is the subject of the film.

But it’s not just an ode to journalism. It’s about dedication to craft, to art and philosophy of art that doesn’t draw a straight line to minimize risk and maximize profit. To investing in the failure it takes to discover success, to greatness. Anderson is one of a handful of American “auteurs” left who will be able to make films for as long as he has the will and original ideas to keep creating. In his championing of Arthur Howitzer Jr. and his small boutique publication, we see a defense of Anderson and his small boutique brand, a distinct style and perspective, a plea to the industry to keep making the movie of ideas, before it is reduced to an abstraction that gooses streaming subscription numbers.

The film spoke to me because of its insistence on quality in the face of the last decade’s demand for endlessly disposable quantity. Howitzer publishes his little paper because he’s dedicated to the idea of it, what it represents in a world moving away from the time and care, the nourishment it takes to produce reporting of merit, to chronicle this ship sinking into freezing water.

Someday this website, a labor of love that has demands our vitality and pays us little to nothing, will be gone and there won’t be anymore middle aged fringe types fighting valiantly, for free, under an assumed name, for the niche prestige movie they just watched and were inspired by, and are begging you, the patient and curious reader, to seek out in reviews like this one. To give a movie, or an obscure regional mixtape, or a raw, bright young writer who can’t get published elsewhere, a chance to incept your brain with their passion. The French Dispatch tells us for now, it’s here, and that’s a good thing. That endeavor, that passion project, is something to celebrate and cherish.

Jeffrey Wright, as Roebuck Wright, worthy of what has been singled out as the film’s best performance, is an iteration of expat James Baldwin. He pitches a profile ostensibly about a French chef that turns into something more. The great metaphor of the film is delivered by the chef, recovering from voluntarily ingesting poison as an act of sacrificial rebellion. The chef, Lt. Nescoffier, played by Steve Park, says “I had a flavor, the toxic salts in the radishes. They had a flavor unfamiliar to me, like a bitter, malty, peppery, spicy, oily kind of Earth. I never tasted that taste in my life. Not entirely unpleasant. Still a new flavor, that’s a rare thing at my age.”

What Nescoffier, and Anderson is trying to tell us, is that there is life in the ending of things. That even the back nine is full of sand traps and pitched greens you’ve never encountered, experiences you’ve never had, and while we tend to devalue these final chapters in our professional and personal lives, the endings of things also have lessons to teach us. That even as the credits roll and lights go up on our rapidly shifting way of life, as we have to say goodbye to more and more of the things we loved and held dear, there are still moments to be had, the nuanced flavors in poison to discover for a final time.