Photo via Mick Hutson

David Brake can adapt to any era, but prefers throwbacks and fitteds.

“Most of the music I like sounds unbalanced,” says John Peel, host of Sounds of the Suburbs, a regional television program that ran on the UK’s Channel 4 in the late 1990s. With each episode, Peel the late British DJ, would visit towns around England, interviewing local acts. A longtime voice on BBC Radio 1, Peel was a prominent tastemaker and a devout supporter of alternative or avant-garde sounds, giving psychedelic and progressive rock airtime long before the genres were accepted in the mainstream.

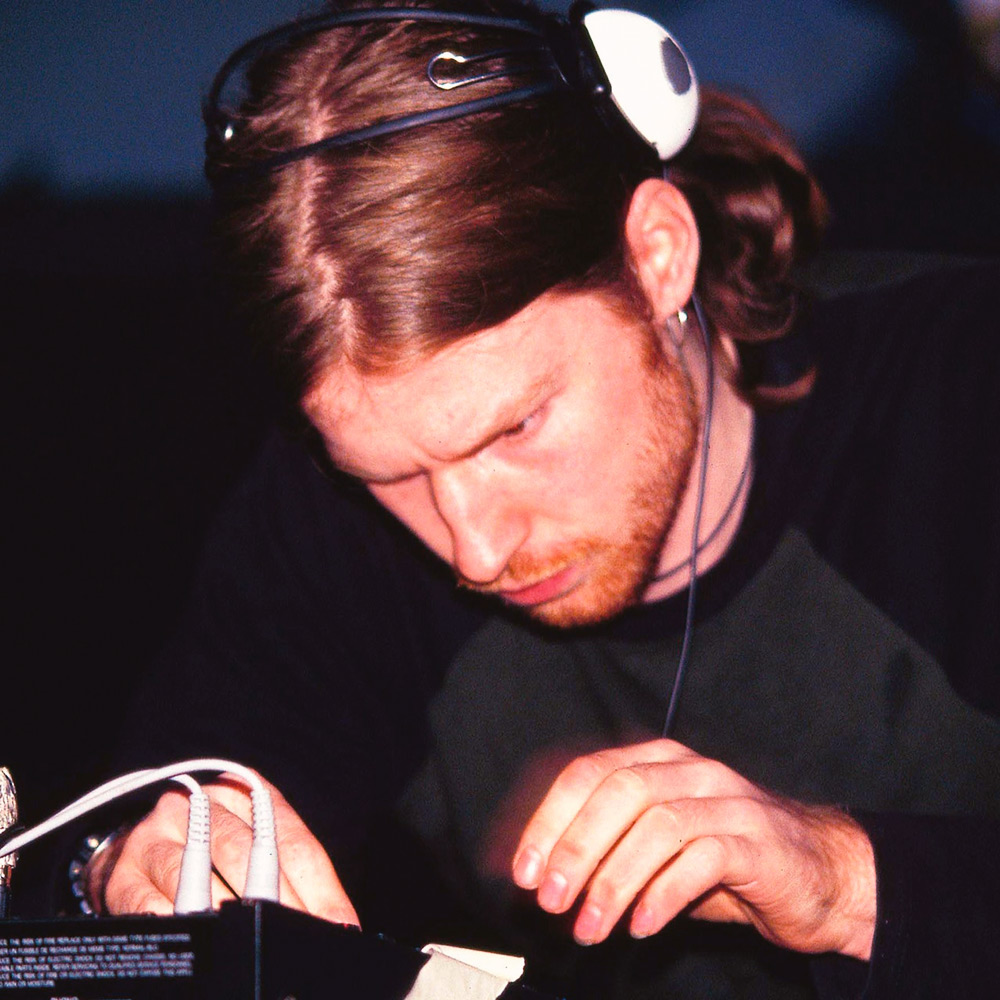

In the video, Peel is cool and confident as he drives through the English landscape — a veteran who has heard everything from brazen ‘77 punk to acid house. Nothing much surprises him anymore, which comes off very clearly in his dry humor and unflinching candor. But something seems off in a 1999 episode when Peel travels to Cornwall to speak with a meek looking and soft-spoken music producer with an infectious grin. His name is Richard D. James, or Aphex Twin, one of the most groundbreaking and celebrated musicians of the last quarter century.

Despite the seasonal visitations by summer tourists, Cornwall was a deeply impoverished county in the late 90’s, a former industrial town which failed to adapt to the new digital age and was littered with vestigial remnants of the past. In his segment, Peel introduces James and fellow electronic composer Luke Vibert as “two of Cornwall’s top toe-tappers,” a label James surely would have hated if it wasn’t so unintentionally hilarious. They’re speaking while overlooking the Gwennap Pit, a recessed amphitheater where Methodist founder John Wesley famously preached to an audience of over thirty-thousand congregants in 1773. James is wearing a leather trench coat and his signature long brown hair blows in the wind.

For much of the conversation Peel seems unaware of what he’s stepped into, like an unknowing guest trapped on an episode of the Eric Andre Show. James bends his reality through manipulation and sometimes flat-out lies, stating that he worked as a miner in Cornwall at the age of seventeen (no evidence suggests this is true); he even clarifies that most of his miner coworkers would work in the nude, with only a simple tool belt slung around their waste (of course, even less evidence supports this). In 2021, James’s manipulation is well known; James has lied about having a submarine (he does not), owning a full military tank (he owns a modified truck), winning a music coding competition at the age of eleven (he did not win), he lived in a bank (another lie), not mentioning countless more. But at the time of Peel’s interview, James is still a half-anonymous enigma whose bizarre interactions with the press hadn’t yet fully unfolded. But despite Peel’s obliviousness to being yanked about, there’s something special about watching the young James craft his persona in real time, right around the time that the Chris Cunningham-directed video for “Windowlicker” would make James an international phenomenon.

James began his music career playing local gigs in Cornwall and its suburbs, steadily releasing music under Aphex Twin and various other aliases (Polygon Window, Caustic Window, AFX, Joyrex, Analogue Bubblebath, Blue Calx, and more). Since those first releases, James has become an untouchable deity within the realm of electronic music, a reclusive composer with a cult-like army of followers who devour his sprawling and byzantine catalogue. James intentionally pushes back against rigid characterizations of him and his music, playing with many different strains within electronic music. He has devised his own singular versions of ambient, drum & bass, jungle, acid house, and Detroit techno. Many have used the term Intelligent Dance Music (IDM) to describe his work, but that label is vague and shows the often pretentious and exclusive nature of his fandom. The mystique surrounding James, paired with the overwhelming amount of music he has released, created a breed of obsessive fans. While many of his followers welcome new members with open arms, there’s a tendency in the Aphex Twin community to intellectualize each seemingly insignificant part of his craft. While the critical discourse can be fun, it can also be discouraging to newcomers overwhelmed with information on where to start.

Each person’s journey with Aphex Twin is inherently personal—given the broad range of music he’s made, every listener will naturally gravitate towards something different than the next. While my entrance began with the Richard D. James Album, you might be pulled in through Drukqs. This isn’t an atlas, but rather a suggestion of where to begin. Broken into three levels each bearing specific recommendations, welcome to the world of Aphex Twin: enjoy the ride.

Enter the Maze

The Aphex Twin universe can be particularly daunting. This is partially because of the sheer volume of music James has released under his various pseudonyms; wading through the hours and hours of music can seem to be an insurmountable task. It can also be a challenge to skirt past the elusive personas which James has carefully crafted throughout the years. Through manipulation in interviews and public communications, secret hidden messages and symbols, and an unpredictable career path, James has created a legion who idolize and pick-apart his offerings, hoping to find insight into his mind. It appears that through his games, James distances himself from the traditional role of celebrity. In addition to rarely taking interviews, he’s a known hermit living far outside of the spotlight.

Although his irreverent approach to fame could be seen as a statement on celebrity culture, he sure does spend a lot of time crafting a polished image with focused branding campaigns and aesthetics, suggesting that his apathy is yet another guise. James would never admit it, but he wants to be understood. It’s why he places easter eggs and messages through his music and image. He might not be embracing the role of a celebrity, but he’s certainly not turning it away. Discovery requires effort, but there’s easier paths than others. Given that we’re covering an artist who was an early supporter of the internet and digital culture, I found it imperative to summon the forces of r/AphexTwin, Reddit’s most dedicated Aphex Twin community, to crowdsource some recommended starting points which were considered when making these selections.

Selected Ambient Works 85-92 (1992)

As the title would suggest, Selected Ambient Works 85-92 is supposedly a compilation of music composed by James from 1985 to 1992 (I wrote ‘supposedly’ because that timeline would suggest James was 14 years old at the time of 1985, a notion which has invoked much skepticism). SAW 85-92 was the first full-length project from James, and although it never experienced the commercial success of Windowlicker and Come To Daddy, it has become one of James’s most celebrated compositions. Sweeping and orchestral, SAW 85-92 plays with the themes of ambient music, but with an influx of melody which balances a cold, robotic feel with deeply human notions of ecstasy and pleasure. On SAW 85-92 we find more vocal samples than most of James’s other work such as the doppler-effected vocals on the intro track “Xtal.” On “Tha,” James experiments with gradually billowing loops, and more avant-garde sounds (a metronome-sounding click surfaces the track’s entirety). SAW 85-92 doesn’t include the more abrasive and off-putting sounds typically associated with cerebral electronic music aside from inklings on “Green Calx,” instead opting for a more familiar approach grounded in the contemporary sounds of house and techno.

Windowlicker EP (1999)

The Windowlicker EP, which arrived in late March of 1999, contains three songs, but has become a fixture of Aphex Twin’s discography from the eponymous lead single. “Windowlicker” stylistically strays from the producer’s previous work and is surprisingly pop-oriented. The track peaked at the 19th spot on the UK Singles Chart and still stands as one of James’ most commercially successful songs. But there’s a deep sense of irony in “Windowlicker,” from the cover artwork to the vocal groans which wail in the background of the track. James presses against the boundaries of pop, watching listeners double taking and questioning if they heard correctly. “Windowlicker” only runs six minutes long, but the narrative unfolds with the precision and drama of an epic poem. James plays with heartstrings as the punchy breakbeat evolves into a fully realized, funk-riddled groove. It’s also particularly endearing that James’ opted for self-sung and unedited vocals to ride atop the melody. It’s a moment of vulnerability on an otherwise clinically constructed song.

Richard D. James Album (1996)

In each person’s journey into the world of Aphex Twin, they inherently gravitate towards a particular sound in James’ arsenal. It’s a notion that was continually brought to my attention when I spoke with members of the r/AphexTwin community, and it can be seen in the endless discourse that surrounds his music. In my journey, the keystone was the Richard D. James Album. From the cascading drums in the opening seconds of “4” to the beehive hum of the melodic “Fingerbib,” the 1996 project presents James less guarded and more comfortable with familiarity and emotion. On so much of James’ work, the producer distances himself from any form of predictability, from the melody to the sonic choices. He works very much in isolation and has expressed fears of becoming subconsciously influenced by other artists, so he rarely listens to music besides his own while recording. His insular work ethic led to groundbreaking and unique music, but it also left James guarded and calloused. He leaned into the lineage of electronic music on the Richard D. James Album, providing familiarity without becoming stale through the use of dreamy House samples freaked with stuttering hi hats and oozing synths.

Going Deeper

Much of the reason why Aphex Twin has become such a monumental and iconic artist in electronic music and beyond is because of the brilliance in his composing, live shows, and adventure. But he’s also become a generational act because of the strange lore which has cropped up around him. He’s a mysterious figure—and he must be. He at once embodies the dichotomy of an ‘everyman;’ he dons a dull color palette, has worn his hair in the same style for decades, and he dresses like that man who stops you on a hike to point out the Robins nest above. But James isn’t an everyman; his understanding of music theory and composition will likely never be grasped by most. The discordant elements of his character partially comes down to branding and his visual aesthetic. Take his logo, a symbol which has been at the heart of Aphex Twin myths and legends since his emergence. It’s an amorphic shape, designed by Paul Nicholson. Some think it’s a bird, maybe it’s a picture of a distorted sound wave? The ‘true’ answer isn’t too exciting: it’s an ‘A’ styled in a very organic font, indicating growth and adaptability. But you wouldn’t be able to convince his fans that it’s not a relic from god—and it may as well be, because with Aphex Twin, there must always be something more.

If you look for conspiracies, you’ll certainly find them within the community of Aphex Twin. But it’s the humor, compassion and uncompromising exploration into the power of music which make James’ work so compelling.

Drukqs (2001)

Aphex Twin’s fifth studio album came into existence in dramatic fashion. According to the lore, James left a hard drive on a plane while traveling. On it laid the unfinished body of work which would later become Drukqs. Fearing a traveler would find and leak the project, James rushed to release Drukqs, which arrived late October, 2001. Perhaps that’s the truth, or maybe the story is just another fantastical tale, but unfortunately for James, the drama would not subside when the music released. Drukqs quickly became the Warp Records producer’s most polarizing album, with many slandering it as irrelevant and stale compared to his previous records. Ironically, his most divisive album contains his most famous song, “Avril 14th.” Sampled by Kanye for “Blame Game” and used in film, TV, and commercials, the simple and delicate piano melody has spread beyond just the cult of Aphex fandom, introducing the masses to the Cornish producer. “Avril 14th” strays vastly from the controlled chaos of his typical offerings, opting for simplicity and a familiar key tone. But listening to the track within the context of Drukqs brings more clarity and showcases the duality of the artist. While there are other melody-forward tracks like “Avril 14th” such as the powerful piano laden “Nanou2” or the building strings of “QKThr,” they’re tucked away between glitchy, fast-BPM songs such as “54 Cymru Beats” and “Cock/ver10.”

Selected Ambient Works Volume II (1994)

The second volume of Selected Ambient Works strays drastically from its predecessor. The songs of SAW 85-92 stand on their own foundation: they each hold their own narrative arc and, to some degree, different thematic elements. But SAW II is a testament to the power of the album format. While “3,” the album’s most popular track, builds subtly from a hum to a soft roar with masterful pacing most producers could only dream of achieving, the songs of SAW II only truly thrive when placed in the broader context of the double LP. There’s something inherently physical about the way James structures the project. It’s built like an elaborate but unostentatious house, full of nooks and hidden details. Where “1” helps to establish the walls of the house, “2” provides insight into the temperate air, and “7” adds mysterious texture. In typical fashion, SAW II doesn’t fully fit into any one genre. It’s too focused on melody to be considered truly ambient, but it also doesn’t ascribe to the robotic tones of techno, or the sample-heavy sensibilities of house. While not as lively as Windowlicker or Drukqs, the complex beauty of SAW II is Aphex Twin in his purest form: unencumbered, wistful, and organic.

Come To Daddy (1997)

If the SAW volumes showcase James’ epic world-building and focused, nuanced sounds, Come To Daddy is the producer at his most brazen. The chaotic and vitriolic sounds of “Come To Daddy (Pappy Mix)” are immediately apparent in the EP’s opening seconds, showcased by a gruesome vocal chanting “I want your soul” looping in the front of the mix. Also included on Come To Daddy is the dynamic “Film,” which features a slightly rushed piano melody paired with heavily programmed and scattered drums. The album is off-putting, even before watching the horrifying music video to “Come To Daddy,” directed by Chris Cunningham, James’ frequent collaborator. As “Film” ends in a lovely melody, there’s no time to process before the squeal of “Come To Daddy (Little Lord Faulteroy Mix)” breaks the calm. Once you find the melody to the second “Come To Daddy” mix, James again subverts comprehension with the digital stuttering of “Bucephalus Bouncing Ball.” I suspect some of the sharp thematic and sonic shifts arise from James’ tongue-in-cheek humor, but it is also apparent that the producer is interested in pushing his listeners’ notions of traditional song structure. Even further, the album suggests James is drawing to question our very understanding of sonic pairing. The vast fluctuations in sound may be off-putting to the common listener, but for James those transitions are deeply organic.

Lost in the Hole

James is fascinated with limits and boundaries. This obsession reveals itself through the intentional subverting of established themes and principles. This resistance can feel stubborn at times, but it also allows him freedom from oppressive normalcy. His resistance to boundaries and limits manifests itself in various ways, from integrating what could be considered cacophonous sounds, to refusing to listen to contemporary music for fear of cross-pollination of ideas. But he’s also fascinated by the limits and boundaries of the equipment needed to make music. James’ rarely speaks candidly about the gear he uses. This is in part, a resistance to the notion that expensive synthesizers, preamps and various effects are needed to create good music. It’s also because James almost never uses stock noises. Where many producers will layer the sounds of various machines to create something new, James builds his own systems, from customizing complex oscillators within synths to the studio’s building itself. The producer recognizes the strange connection between something as tangible as a piece of electronics and the ephemeral nature of music.

In this final stage of the Aphex Twin journey, I focus on moments of unhindered experimentation which succeed sonically to varying degrees but serve as foundational pieces of James’ craft.

Digeridoo EP (1992)

The Digeridoo EP is one of James’ most bold and unhinged offerings to date. As the title suggests, the EP focuses heavily on the Aboriginal wind instrument, stretching its use and finding unexpected sounds in the process. The eponymous track begins with a wailing didgeridoo before it devolves into a drum and bass fever dream. The track is entrancing and sharply unique, but still provides enough familiarity for comprehension. Less could be said about the laser-beam sounds of “Flaphead,” which unpredictably chop for seven minutes. “Phloam,” borders on TV-static, only occasionally exposing an underlying melody hidden deep within the roar. Sounds of Acid House bubble on the final track “Isoprophlex – AKA Isopranol,” providing little reprieve and even less closure. But these moments provide a clear look into Aphex Twin’s priorities: he only explores what interests him, and cares little for the finished product’s digestibility.

Donkey Rhubarb EP (1995)

Donkey Rhubarb is often left by the wayside when discussing Aphex Twin’s discography, but the four-song EP is revelatory. Experimenting with a distorted combination of acid house, jungle, and even hip-hop beats, Donkey Rhubarb is playful, light, and surprisingly approachable. The title track features a palpably oozing melody which dances on the upper register, sometimes allowing a twinkling piano to peek through the fray of the drums. “Vaz Deferenz” sounds like a swarming hive of digital bees. “Ict Hedral (Phillip Glass Orchestration),” a collaboration between James and the legendary composer reimagines an Aphex Twin track, scored with grandiose orchestral instrumentation. “Pancake Lizard” wanders even farther for the mold, delivering an uncharacteristically minimal beat which sounds as though it came from an underground boom-bap album.

SoundCloud Dump (2015-2020)

James has never released music in a traditional fashion: there’s rarely rollouts or marketing tactics beyond a few mysterious announcements. So it was unexpected when fans found an anonymous account on SoundCloud leaking Aphex Twin’s archive. There’s never been a definitive consensus, but it’s highly suspected that James was self-releasing his archive (which amounted to almost 300 songs in total). Included in the archive are remixes and early rendition of several previously released Aphex Twin records, as well as original compositions which never saw the light of day. The archive boasts songs from various stages in James’ career, and with hours upon hours of music to explore, contains something for every breed of Aphex Twin fans. For an artist of James’ caliber, who dominates media cycles and electronic music discourse every time new music is released, dumping a large swath of his personal archive is a bold move. But it goes again to the power of the Aphex Twin community: his music lives through his listeners.

Outro

“Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself,” could have come straight from James, though it likely would have been spoken with a slightly more playful barb. James is as amorphic as his music. He resists any anchors or borders and sacrifices what’s holy in order to do so. This rigid (at times, stubborn) aversion to categorization has led to being adored by everyone from Björk and Madonna to Karlheinz Stockhausen and Squarepusher. His presence, which, through rumors and legends, lives actively in the world despite James’ reclusive nature, has become a mirror which points back towards the listener. His fans dictate who he is, what he will be to each of them. For some, he’s a brilliant stowaway, a once in a generational talent. For others, he’s the face of mischief and uncompromising self-expression. For others yet, he’s pretentious and arrogant.

James is also walking evidence of the difficulty of separating the art from the artist. His work lives and breathes through the legends he’s created. While anyone capable of producing albums like Selected Ambient Works 85-92 and Drukqs would be celebrated, his presence creates myth.

Aphex Twin’s discography runs in a circular pattern. Temporal notions are suspended as you enter his gates, like a Cornish Dante on acid. As you wander through the kaleidoscopic valleys of his music, you’ll find no two laps are the same. New sounds will become unearthed like sproutlings, exposing themselves on tracks you’ve already heard, cities constructed from warbling bass and wafting drums. You’ll find James, or rather a distorted portrait of him. But you’ll also find a mirror, pointing sharply back at yourself. If you look hard enough, you can watch the reflection change before your eyes.