Abe Beame knows that there will always be one true Weekend Update host.

The legends surrounding the creative marriage between Biggie and Puff produced a simplistic narrative. It goes like this: the greatness of Ready to Die and Life After Death were the product of tension, a push pull between Big’s desire to make rugged and grimy shit, and Puff’s pop inclinations. The oft-quoted example is, according to legend, Big wanted “Machine Gun Funk” as the lead single off his debut, Puff insisted on “Juicy”. This tension produced what many refer to as the modern rap album, a cinematic 31 flavors approach invented by Bad Boy, cohesively melding street records with accessible, “softer” hits, that remade the great soul and R&B records of the 70s and 80s. Ten years later, it was brought to its logical and cynical Marvel formulaic conclusion by 50 Cent and G-Unit.

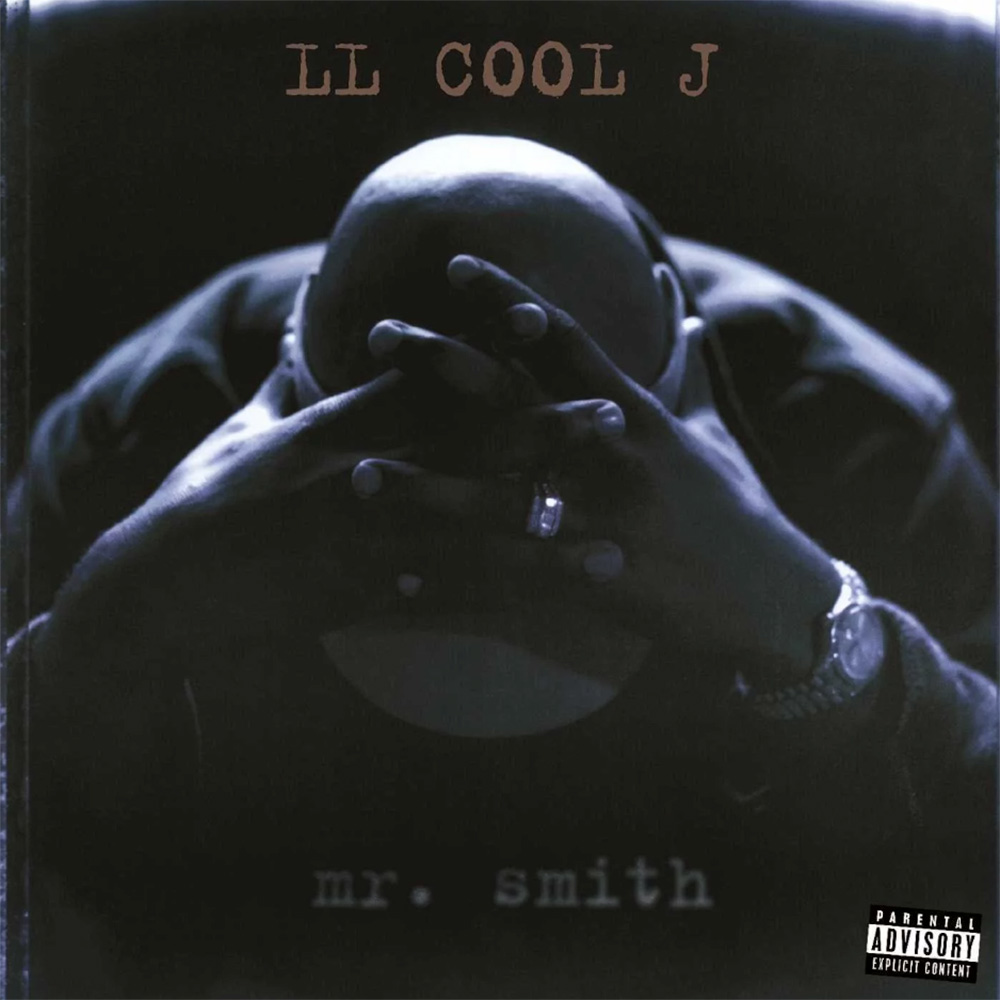

Released in November of 1995, LL Cool J’s Mr. Smith is an interesting outlier, a sliding doors moment/What If issue in which Owatu posits: “What if in 1995, Puff didn’t have to fight with Big? What if he had found the perfect avatar, the mainstream conduit of his philosophies and values to execute his grandiose soft serve vision?” The album came just a year after Ready to Die, and two years after LL jumped on Craig Mack’s all-star remix to “Flava in Ya Ear”, Mr. Smith is the greatest Bad Boy album released off label. If Lil Kim’s Hardcore is the lost Biggie album, Mr. Smith could be considered Puff’s lost contribution.

Mr. Smith was released by LL’s longtime homebase, Def Jam, but smuggled Puff’s sensibilities, along with an all-star team of Bad Boy affiliates, onto an album that essentially relaunched what had been LL’s recently stalled career. There’s a tendency to attribute outsized influence to Biggie as the rapper who trademarked what the East Coast leaning rap album would sound like for the rest of the 90s, but that isn’t accurate.

Big’s uncommon skill and genius made him impossible to reprint. The generic, popular tri-state rap album of the mid to late 90s would actually hew far closer to Mr. Smith. In many ways, the album is a missing link, an invisible bridge, the way something thorny and weird and personal can become an algorithm that labels can make money off, but is in no way a sureshot. It took a veteran — and in many ways a genius — to translate the dead language that made something as singular as Ready to Die possible without its author.

Mr. Smith opens with an interpolation of The Good, The Bad and the Ugly. As presented, James Todd Smith is a gunslinger saddling into town as his spurs jingle. While the stoic and macho implications of Clint Eastwood’s nameless protagonist don’t fit the album at all, it works as another mercurial chapter from a rap legend with a gift for reinvention. A stranger who walks into a genre town and makes it his own. The veteran had made a career of that sort of impossibility in an industry with clearly defined identity restrictions. At the time, and even today, a 10-year rap career was unheard of.

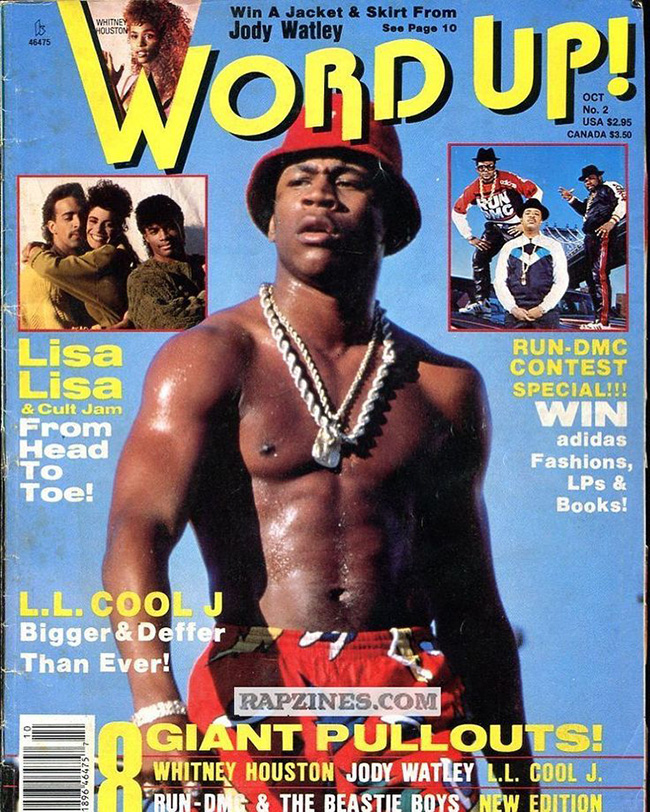

LL got to 1995 by proving himself as what still qualifies as one of the most dynamic pop talents we’ve seen in any genre — a quality we deny rappers in this authenticity-driven medium, but conversely praise artists like Madonna for. He emerged at the Roxy as a Kangol crowned high school dropout from the future, blowing minds performing Chuck Berry at his parents’ prom. He made his bones with a punk producer making a punk album that assumed the form of rap. It was raw and elemental and took the noise produced by fellow Def Jam rock/rappers Run DMC and The Beastie Boys, and managed to somehow crank the volume.

LL’s career began at a time when rap was still pre-adolescent, in a Vaudeville-like fugue state in small niche markets, each act sent up by a label with an angle and a bit. Rap names were like graff tags: weird and funny monikers you could imagine stenciled into the margins of a spiral ring notebook, or etched onto a subway car window. But L was different, a solo act at a time when nearly every rapper was a member of a group or collective. He was well-rounded and not limited to a particular sound. By his second effort in 1987, he shuffled “I Need Love” into the mix alongside “Go Cut Creator Go” and “.357 – Break It on Down” and was better than his peers wearing either hat. In L, we get a sneak preview — a blueprint for what the future of modern rap stardom would look like. He displayed an effortless dexterity and malleability that we’d see once a generation.

But there was blood in the water. Rival rappers saw this dexterity and malleability as weakness, a lack of voice and conviction. Treacherous Three MC Kool Moe Dee went at him. He thought he saw a soft target, a mistake others had made and would make again.

The attack pushed LL to noir, the direction that hip-hop as a whole was moving towards. He’d follow 1987’s Bigger and Deffer with 1989’s Walking With A Panther, 1990’s Mama Said Knock You Out, and 1993’s 14 Shots to the Dome. All three albums are littered with hits that are in L’s voice, but the meat of the albums find their lodestars elsewhere. Panther finds inspiration in Big Daddy Kane’s conversational punchline heavy spit, while Mama and 14 Shots, both helmed by Marly Marl, would channel the hellfire of Kool G Rap and Chuck D on the former, and the rapid spit over chaotic production of Marl proteges Lords of the Underground on the latter.

A few years ago, I wrote a piece about Drake’s rise to prominence in the 2010s, comparing him to Leonardo DiCaprio’s depiction of Frank Abagnale in Spielberg’s Catch Me If You Can, “a fraud and chameleon that is often more convincing than the text he is appropriating.” But it’s just as applicable to L in the ‘80s and ‘90s, the closest thing Drake has to a spiritual ancestor. They’re both master forgers, both consummate survivors who have a knack for understanding where the wind is blowing in music and culture. These LL albums, including the underrated 14 Shots to the Dome, are all good to classic, but from project to project, they present very different versions of their author. Mr. Smith isn’t quite that. It’s as different from its predecessor as it could possibly be, but feels like a homecoming. A return to form.

The Trackmasters are a production duo consisting of Samuel “Tone” Barnes and Jean “Poke” Oliver, two city kids who connected in Brooklyn. They had gotten down with Puff during the early Uptown days. Tone worked with Big when Tone was still an artist and Big was a phenom with a demo that had landed him a Matty C feature in Unsigned Hype. Tone also worked with Puff at Uptown, writing for an R&B duo called Finesse and Synquis.

But as a production team, the Trackmasters had laced an R&B boy band called Soul For Real with 1994’s “Candy Rain”, an appropriately sacherine confection that crossed over and probably would’ve ended up on Mr. Smith if L got to it first. Soul For Real was an Uptown outfit (of course), and they had been recruited by Mount Vernon legend Heavy D. But the Trackmasters didn’t stay under Hev and Uptown head Andre Harrell for long. They were soon poached by the greatest talent scout in the game:

“When Andre Harrell came into the studio and was like, ‘Yo this is nuts!’ Puffy came in the studio too. Puff was on some real competitive, whisper sh*t like, ‘Why you giving this ni**a Hev hits? What are you doing? Yo, I’m working with Mary ni**a. You wanna do Mary? What are you doing? You doing music? Come on, B.” – Poke

From there, they worked with Mary, still on Uptown for “Be Happy” and “No One Else” off 1994’s classic My Life. They produced “Juicy”, the “One More Chance” Remix, and “Who Shot Ya?” for Big. During the making of Ready to Die, Poke lived in Scarsdale with Puff.

The Trackmasters used a simple formula to produce their hits. They would “fade” the kicks and snares from an instrumental by breaking the sample into 100 pieces, then supercharge them with their own drum kits. In the mid-90s, it was a time-consuming and tedious process, but it was the sound that Puff had striven for, simultaneously conserving the unchopped integrity of his source material, that vast library of great pop no one had been able to access yet, while updating the sound in a way a casual would have a difficult time pinpointing. Using this formula, the Trackmasters became a conduit. All these off-tempo samples from the glory days of disco and soul could suddenly be made rap.

If you have a second, step away from this review, listen to Debarge’s “Stay With Me”, then listen to Biggie’s aforementioned “One More Chance” (Remix), maybe even on top of each other if you can stand the chaos. The former is a gorgeous, mellow, vacuuming-the-living-room-on-a-Sunday-afternoon Soul Train ballad. At least that’s what Poke heard. But Puff heard a hit. He heard an anthem. Of course, he was right. The results speak for themselves.

The Trackmasters wanted to keep that vintage, vinyl quality. They made music that lived on the tip of your tongue, in a warm and familiar place that could still be new and exciting. It was a perfect marriage of executive and producer. Puff finding Tone and Poke was Billy Beane finding Paul DePodesta: the visionary found the math that ordered a chaotic brain, that put logic and reason behind an idea that was big and vague but undeniably there to claim for the person with the means, and the will. With the Trackmasters and their in-house team, the Hitmen, Bad Boy opened the broader possibilities of rap:, how it sounded, how it played, who it could be made for, who was ready to receive it.

But the Trackmasters fell out with Puff in 1995 after retaining Steve Stoute as a manager, and several years of getting their credits robbed while making smash hits for Puff’s artists, culminating in a straight up robbery when they turned Rza’s dark and weird version of Method Man’s “All I Need” into a song of the Summer remix with Mary on the hook. Puff took the credit, and the duo said “Never again”. They had attended Bad Boy finishing school, and were ready to make their own hits.

It started with “Hey Lover”. The Trackmasters had made a strummy, dreamy R&B leaning beat out of Michael Jackson’s “The Lady In My Life”. With Chris Lighty serving as connective tissue, they played it for LL at his old haunt, Chung King studios, which had recently moved from its space above a Chinese restaurant on Centre Street to a penthouse on Varick. L lost his mind, and immediately came up with a deranged, Quixotic vision: He had to have Boyz II Men on the hook. The R&B quartet was at the peak of their powers, and ungettable for something as paltry as a guest hook, so L and the Trackmasters drove to Philly, ran up on Wanya Morris in his white Range Rover on the set of a video shoot, and played the instrumental track while L spit his rhymes. The group fell in love with the concept on the spot, immediately went to their studio in town, and recorded the song off a loop from the cassette the Trackmasters brought with them. That’s the version that made it to the radio, and immediately took over the world.

“Hey Lover” essentially invented the after-school pop that would dominate the 106 & Park demo a decade later. Other rappers, Big and Puff included, had taken stabs, but nothing that came before had the nostalgic shimmer, the command, the butterscotched voice spitting game on Farmers Boulevard, kicking-through-gold-and-brown-fallen-leaves-with-matching-Timbs-and-puffy-North-Faces patois that L nails here — the kid from “ I Need Love” had grown into a fully-formed, jacked, moist-lipped commando with an elastic band wave cap under a fitted FUBU, hard yet sensitive, wholesome and illicit, the sentient result of a 12 year-old girl in St. Albans making a wish on a topless Word Up! poster tacked to her wall, bringing that idealized teen pop image to life.

What followed was two manic weeks at Chung King that would result in seven songs, the lion’s share of Mr. Smith. L and the Trackmasters have ingested all the lessons taught by Puff and Big’s revolution, delivering a front to back ALBUM that isn’t without skips, but has that ineffable quality of containing something for everyone, infinitely replayable in nearly any situation or circumstance. The album is a marriage of Rap and R&B that we hadn’t really seen before. The closest point of reference would probably be Mary J. Blige’s “What’s the 411 Remix”, but of course that was the work of a singer dabbling in rap beats, inviting rappers onto niche versions of her songs.

This is LL, the great escape artist, the master of reinvention, finding a new lane as a rapper turning what was once the rap guest verse into the entire meal. He moves the emphasis from the bullshit to the rap. Mr. Smith is nothing less than a genre-bending evolution, an album with nods to an audience that was increasingly less demanding of hardcore authenticity, and more interested in songs that could cross barriers not much rap had been capable of traversing up to this juncture.

There are street records on Mr. Smith, mostly bad, but he made the intelligent decision to drop the diet Das EFX stuff he was doing over Marley Marl production on 14 Shots. Produced by longtime Big collaborator Easy Mo Bee, “Life As….” is the worst song on the album (with strong competition from the great-sounding but bad to pay attention to “Hollis to Hollywood”), but it’s not that bad, and without the awful hook, it’s listenable. But more importantly, stabs like these were mandatory for a serious, Source approved rap album in 95 (4 mics). These were the prices of admission that allowed him to make these androgynous, gorgeous hits. It’s like how Mike D’Antoni’s Suns shot less threes than they could’ve, than they should’ve, because they didn’t realize it was possible to just lean all the way into the table-upending chaos at the time. What stands out now, even with its cringey moments that have aged poorly, is how great a rapper, how comfortable L is in the pocket, on the beat. On any beat.

But it’s not just a singles album. There are some days, albeit few and far between, I actually prefer the Al B. Sure sampling original take on “Loungin” to the Total assisted, steroidal remix. And “I Shot Ya” (Intended for Biggie and produced by Nasheen Myrick with Poke on smoothing duty) is just mask-off. It’s actually a good song, but such a naked Biggie rip L can only bare to change a single word from the title of its inspiration. The ironically named “No Airplay” is just great. A lyrical showcase of L’s limitless talent that also serves as a preview of his classic late career Funk Flex hit, “Ill Bomb.”

Then, of course, there’s “Doin It”, a song beamed in from another album, from another era, on another planet. It was produced by Rashad “Ringo” Smith, born in England, raised in Brooklyn, the product of a Jamaican and Hatian family who started as an Uptown producer and eventually moved to Bad Boy as part of the Hitmen collective. It’s a sample of Grace Jones’ “My Jamaican Guy” that retains the original’s tawdry sweat and chintzy dancehall funk. With the possible exception of “Too Close”, it’s the strangest, horniest song ever played at a middle school dance. It’s a BDSM fantasia that reeks of a cheap outer borough hotel room near an airport, two seasoned phone sex operators rising to the level of their competition as they collaborate on one of the greatest pop songs of the decade.

Mr. Smith spent 62 weeks on the Billboard 200 and the album sold over two million copies. “Hey Lover”, “Doin It” and “Loungin (Remix) were all top 10 singles on the Billboard Hot 100, and LL won his second Grammy for “Hey Lover”. One year later, in November of 1996, LL released All World, a platinum selling 17 track career summation, which is, perhaps, hip hop’s best ever pop rap greatest hits album. In a time before streaming or the internet, this was how a new generation of fans discovered the rapper/actor they primarily knew as Marion Hill from the sitcom In the House (now in its second season), the guy who had just dropped a hot album the year before, had been doing this for over a decade and was actually one of the greatest rappers who ever lived. In a career full of impossible heights, this may have been his late, unlikely zenith.

Many artists would follow Mr. Smith’s blueprint — often minus the charisma, the ideas, and the songs of the smash hit. This included L himself. Puff would actually EP L’s next album, the lackluster Phenomenon, which by 1997, in the wake of Mr. Smith is somehow further away from the Bad Boy sound he hit on with the Trackmasters. The Hitmen and the Trackmasters produced a bulk of the 10-track album, but it plays like what was left on the cutting room floor from the Mr. Smith sessions. Something you find with LL’s catalogue through the years is a successful jump to a new approach, a new style and sound, with a subsequent attempt to capitalize on the same approach, yielding diminishing returns. Phenomenon is no exception. A failed attempt to recapture lightning in a bottle.

But for me, what’s beautiful about Mr. Smith is it’s an example of an artist coming full circle, surviving long enough to watch the cyclical trends in music come home. Because he’s on the shortlist of the greatest rappers who ever lived, LL was able to tread through the choppy waters of the late ‘80s and early ‘90s as rap went dark and hard. He adapted to the times, won some crucial battles, and deserved all the cred he fought for. But with Mr. Smith, life and time rewarded a rapper with arguably the greatest pop instincts of all time. Fitzgerald said there are no second acts in American lives, but here is Uncle L, 10 years in the game, on his fifth iteration, back in his wheelhouse and on top of the industry. It gave him the opportunity to deliver a gift to a once again receptive world, directly from what has always been his brimming, candy coated heart. For one final, brilliant moment, L embodied the past, present, and future of the funk. It was a battle we all won.