At what would be J Dilla’s last show in December 2005, DJ Deckstarr, the opening DJ wore a custom-made shirt with “J Dilla changed my life” printed in large capital letters across the front. In the years since, family, friends, and fans have echoed this sentiment when showing love for the influential hip-hop production virtuoso who passed away sixteen years ago this month at just thirty-two.

Many know Dilla’s story. Or at least they think they do. The Detroit-born and bred producer/emcee was always more interested in making beats than doing or talking about anything else. His days consisted mostly of record shopping, for what could be hours at a time, before heading home and listening meticulously to every song on each record in search of samples he could use in his productions. The time he spent innovating his sampling technique paid off, drawing the attention, and eventually admiration, of peers like Busta Rhymes, De La Soul, and members of The Soulquarians collective. These masters in their own right would be left speechless after witnessing Dilla at work. But they were not alone in recognizing his inimitable approach to beatmaking.

Hip-hop historian, Dan Charnas, heard Dilla for the first time at an album release party while living in Los Angeles back in the mid-90s. Charnas, who was already an established journalist at that time, would go on to work with Dilla in the late ‘90s before taking a hiatus from hip-hop to pursue a career in screenwriting.

Charnas noticed Dilla’s influence finding its way into hip-hop’s soundscape the same year he was accepted into Columbia’s Graduate School of Journalism. He was motivated to pursue an interview with Dilla for a piece on the artist’s signature sound that would never be written.

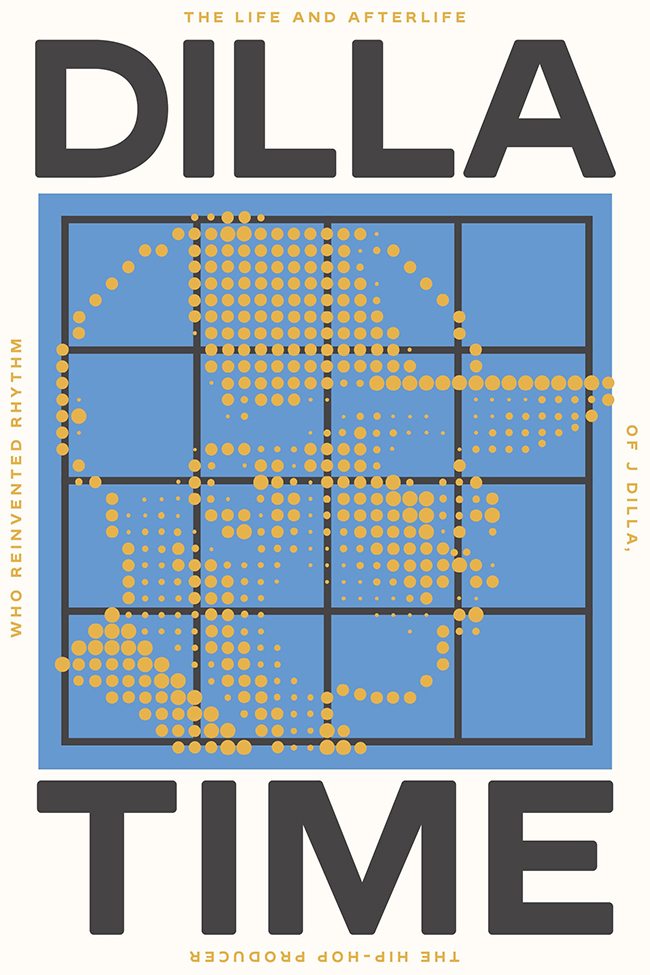

More than a decade later, Charnas, now an associate arts professor, designed a course called “Topics in Recorded Music: J Dilla” for the Clive Davis Institute of Recorded Music at NYU, which is where he developed his theory of Dilla Time. This course, and the methodology Charnas would unpack over the span of seven weeks, would ultimately serve as the impetus behind his latest work, Dilla Time: The Life and Afterlife of J Dilla, the Hip-Hop Producer Who Reinvented Rhythm.

The book is structured as a grid because that is what Charnas believes will make the most sense for readers, especially fellow beatmakers. What started out as more of an abbreviated discourse on Dilla’s unique process evolved over four years and 200 interviews into an in-depth account of the artist’s biography, including intimate details of his illness and relationships with Ma Dukes and the mothers of his children, juxtaposed with lessons on rhythm and grid illustrations.

Charnas made a point to not allow the pages to be crowded by footnotes, and, as someone with a novice-level understanding of music theory, I appreciated the extra time he put in, breaking down the technical terminology integral to filling out the narrative side of Dilla’s story. When I spoke to him in the days leading up to the release of Dilla Time, Charnas was significantly more cool and confident than when he and I last connected more than two years ago. He understood better than anybody the impact his book would have on family, friends, and Dillologists alike but also the importance of ensuring Dilla’s legacy is maintained, and maybe more importantly, recorded. – Lara Gamble

What is your earliest memory of hip-hop?

Dan Charnas: I’m older but not from New York. So, my first memory of hip-hop is like so many people in my generation hearing “Rapper’s Delight” for the first time, probably on the radio, maybe on somebody’s boombox. I was either in sixth or seventh grade in middle school in suburban Maryland and just hearing the same sort of thing. “Well, it sounds like ‘Good Time’, but it’s not. People are talking over it.” And, of course, it was everybody’s favorite song after that. How do you not love it?

You majored in Afro-American/Urban Studies and Communications at Boston University before becoming one of the first writers for The Source magazine in the early 90s. How did your role as one of the original hip-hop journalists influence your career trajectory?

Dan Charnas: That’s an interesting question. I think it was the trajectory. I knew by the time I was a senior. I’d spent the last year in college writing this thesis on racial segregation in the music industry. So, I had already, because of that, made some inroads into the hip-hop business. But, at the same time, hip-hop is entering its true lyrical and musical golden age. We’re talking ’88, ’89. And I knew I could pretty much get a Fulbright scholarship or go on to grad school. I was like, “No, I want to be a part of this hip-hop thing and helping [it] get to where it needs to be.”

Because again, it was political for me. Like, “Oh, this is pop music.” No pop stations are playing it. Barely any Black stations are playing it. But this is it. I guess you could look at it like what rock & roll was to the 50s. Hip-hop, I was sure, would be that to the 80s. So, I just took any job I could find. I wrote press releases for this new label called Wild Pitch. I took a job in the mailroom of Profile Records, and while I was at Profile Records, there was this little magazine out of Harvard that was all hip-hop. You didn’t have a magazine that was all about hip-hop ever! It was as simple as calling Jon Schecter, finding and calling him, and saying, “Yo, I love this.” And he was like, “Come help.”

I was already writing about hip-hop for the Boston Phoenix and other places. I was already sort of published in hip-hop. That made it easier for John Schecter to have me in. And that became the trajectory. So, there was a part of me that was working at the record label and then there was a part of me that was writing about hip-hop. But it was all organic, and none of it was mainstream or popular or anything but fringe. But that was the community.

Your 1989 paper, “Musical Apartheid in America: The Sociocultural Ramifications of Racial Segmentation in the Music Industry” examined white America’s 400-year-long relationship of ambivalence to Black culture, the legacy of racial segregation in the music industry, and the potential of hip-hop in resolving that ambivalence, transforming the industry and the entire culture. Why was this topic So important to you?

Dan Charnas: Because I grew up in it, and it made me very angry. I grew up in an integrated town, but I also grew up in that town during one of the most segregated times in American culture. The late 1970s, early 1980s, when Black artists were being driven off of radio, where MTV debuted and didn’t play any Black artists, period, because Black music was seen as this other thing. And even I knew, at age thirteen or fourteen years old, that the guys wearing the jean jackets and listening to Led Zeppelin, that what they were listening to was the blues. They were listening to Black music. It was just older and in a white form.

So, the injustice of all that was what drove my study. And it wasn’t foregone that I was going to be doing that in college. As hip-hop evolved, as my own politics began to evolve, that was the project that I wanted to do. And, so, it was a 125-page paper on the ways in which Black artists and Black art are deprived of access and thus deprived of equity.

You touched a little bit on this before. Can you talk a little bit about how your career in the music business started in the mailroom at Profile Records and not even two years later, you were tapped by Rick Rubin, at the young age of twenty-five, to build the hip-hop music department from the ground up as VP of A&R and Marketing at American Recordings?

Dan Charnas: My summer job was working for George Wein’s Festival Productions, which, if you know, George Wein created the Newport Jazz Festival, and then he created the jazz festival in New York, which became the JVC Jazz Festival. And I worked in the ticket office and in other departments at Festival Productions on the west side every summer. But everybody there knew that what I really liked was hip-hop. And, so, that third summer after I graduated, I just started sending my resumes out to every single one of those indie rap record labels: Next Plateau, Profile, Tommy Boy, Select, and Corey Robbins from Profile saw my resume and asked me to come for an interview for the mailroom. He said, “What music do you like?” And I just rattled everything off, and he said, “Okay, that kid.”

And listen, our tastes were not aligned. There’s a story that I tell about when he first promoted me from the mailroom to do A&R and promotion. He said to me when he hired me, “Listen, you can’t know what’s going to be a hit. You can only know what you love.” And, of course, I kept bringing him stuff that I loved, and he kept not signing it.

So many, many years later now, I’m going like twenty-five years later. I’m now an author, and Corey and I are sitting down for a drink, and I said, “Corey, you know, back in the day, you said, ‘You can’t know what’s going to be a hit. You can only know what you love.’ And I had an A&R career that was not as successful as yours, not nearly as successful. I didn’t sign hits, and you signed hits, but I signed what I loved. Why were you successful, and I wasn’t as successful?” And he said, “Oh, that’s easy, I love hits.”

Whose idea was it to include “Game of Charnas” on Red Foo & Dre Kroon’s album Balance Beam in the late 90s?

Dan Charnas: It was Red Foo’s idea. I was a part of the Wake Up Show crew when they moved to L.A. Sway and Tech started in San Francisco. Then they moved to L.A., and I would do these little readings, like poetry readings of rap lyrics on the Wake Up Show for a goof. So, I did “Brooklyn Zoo”:

I’m the one-man army, Ason.

I’ve never been tooken out.

I keep MCs looking out.

You know, even saying, like, “Nuh!” You know, all that. So, it became a thing. And Red Foo was like, “Yo, can you do that on my album?” I have these very weird little cultural moments. So, that was one of them.

Another one was, Rick was way into techno, and he signed this tiny British label called XL Recordings, which, of course, you now know is the home of Adele and Richard Russell. It’s huge. But back then, he was just my homie Rich. And when I came to London in ’93, he’s like, “Yo, Dan.” I went by the office, and he was like, “You know, The Prodigy has this record where there’s this sample we can’t clear, and we need an American accent. Can you do that accent?” He talks about this in his book. And so, I do this American accent, and it is on the beginning of The Prodigy’s record, “Their Law.”

And, yeah, I kind of blow my students’ minds. They were the Chuck and Flav of techno. So, Red Foo, man. Yo, he was just super dope. I remember going over at his house to do that, and he became a huge star.

You signed Kwest Tha Madd Lad to American Records in the mid-90s and produced three tracks on his debut record, one of which was the single “101 Things To Do While I’m With Your Girl.” @DadBodRapPod mentioned being disappointed about not asking about it during your interview, so I figured I’d step in. Are there any memories related to that project you can share?

Dan Charnas: I carried two artists with me from Profile, who I couldn’t get Corey to sign to Profile, to Def American. Kwest was one of them, and Chino XL was the other. Kwest I ended up officially signing in ‘92 or ‘93. We worked on this incredible album. It was all super low budget but super creative. Kwest was one of the funniest, most creative, and, God bless him, he allowed me to be funny and creative with him. So, we had a ton of fun making that album.

I was lucky enough to have a photographer friend of mine in Los Angeles, by the name of Brian Cross, come to New York with us to do those photos. I have a memory of Brian Cross. The album’s called This Is My First Album. And, of course, what do you do with your first album? You go and you give it to your mother like it’s some homework, and she puts it up on the fridge with a magnet. So, I said, “Okay, we need to go find a refrigerator, and we’re going to show his mother putting the cassette on the fridge with a magnet.” Just stupid!

So, Brian came with me to my grandmother’s house, Kwest and Brian. We were in my grandmother’s apartment on the Upper East Side. This is the same building where Liza Minnelli and Howard Cosell lived. So, yeah, I brought Brian Cross into that, and that is why, my friend, I can do a book like Dilla Time and have the help of somebody as magnificent as Brian Cross because homie was with me! Yo, we had fun that day.

It was just fun, and it’s still fun. If you listen to that album, you can’t believe that somebody would make something this sprawling and stupid and creative. It really is just a fantastic album. The first track is called “Everyone Always Said I Should Start My Album off With a Bang.” It’s Kwest with his cassette player under his bed fucking a girl. Yeah, fun times.

In the years to follow, you held multiple roles at varying editorial outlets. After having already achieved a significant level of success in the industry, why did you decide to go back to school to earn a master’s degree from Columbia’s Graduate School of Journalism?

Dan Charnas: Rick lost his distribution deal with Warners at the end of ‘97. I went on to work for Forest Whitaker who started his own record label through Sony. I was in the kind of situation where you’re sort of pushing all these buttons, but nothing’s happening. I felt like I was just unable to make things happen musically. I was producing. I was doing tracks and stuff like that. But it was like I had one foot in the A&R world trying to be an executive and kind of only half-stepping my production career. And something was misaligned for me. And working for Forest was a great opportunity, but it was not easy because we had no control over what we could and couldn’t release.

I wandered in the wilderness a couple more years, and then finally said, “L.A. is not my home. It’s never been my home. I miss New York. I want to come back.” I didn’t know what I was going to do. All I knew was that I did want to write. I had sort of lost my network. John Schecter wasn’t an editor anymore. James Bernard wasn’t editing anymore. My people were not in place. So, I was really starting over in my mid-thirties. And it was scary, but I had no expectation of anything. I thought maybe that part of my life was over, the whole hip-hop entertainment business. Maybe I’ll be an accountant.

But I knew I did want to write. So, I said, I tell you what, I’ll roll the dice. I’m going to apply to the Columbia Journalism School. And if I get in, I’ll go. But I’m not going to apply anywhere else. If Columbia won’t take me, then I’m not going to do it. And they took me. In 2005, I got accepted into Columbia, and that gave me this very important thing, which is a new foundation.

When you become a student at Columbia, you pick a beat, a neighborhood, in New York that you want to cover. The neighborhood I picked was Hunts Point in the Bronx, which is the home of the huge wholesale food markets for vegetables, fruit, meat. And they had built all of these things in Hunts Point with the promise that the locals would get jobs there. And so, as part of the beat, you literally walk the streets, and you have to try to find sources cold.

I didn’t know anybody in the Bronx at that point. I decided, ultimately, my final project was going to be: “Do the residents of this neighborhood actually work in the markets?” I don’t know if you’ve ever seen the Hunts Point Terminal Market, but it’s designed by the same architect as the Hartsfield International Airport in Atlanta. There are buildings laid out in four long rows, and the offices are upstairs, and it’s literally a hallway that is a quarter mile, or a half a mile, long.

I remember, in 2005, walking down that long hallway, knocking on a door, knocking on another door, knocking on another door, and thinking, What the fuck have I done? What have I done? What am I doing here? I worked for Warner Brothers. What am I doing as a journalist student in the fucking vegetable market in the Bronx? But I think about that moment as a real turning point for me because one of those doors did open. You have to keep knocking. One of those doors did open, and that’s how I found what I needed.

And I was worried. I went back to my professor, and I said, “I don’t know that I’ve reported enough.” She looks at me and she goes, “You reported plenty. You over report.” And that became, obviously, my signature.

What did it mean to be awarded the 2007 Pulitzer Traveling Fellowship by the Graduate School of Journalism, its top honor?

Dan Charnas: It came as a complete surprise, a shock. I’d never really won an award. I’d won a Maggy Award. I was writing for Yoga Journal for a while. That’s a whole other part of my life because I became a yoga instructor and teacher in Los Angeles when I was there. So, it was a complete shock, but it was great.

And it was nice to be able to show that to my parents after coming back to New York. You know, this failed career. My father’s still trying to get me to be a lawyer. It’s funny because, weirdly, that same day, I won the journalism law class award. And I whispered to the dean, Nicholas Lemann, famous journalist. I said, “My dad would be so proud because he’s still trying to get me to go to law school.” So, of course, he told the audience.

Your first book, The Big Payback: The History of the Business of Hip-Hop was released in 2010 and has since become known as the most definitive book on the industry and the culture. What did that kind of response mean to you back then, and does it still surprise you to hear about its influence more than a decade later?

Dan Charnas: I saw that there were some fantastic books coming out about hip-hop. The two that set the bar were Jeff Chang’s Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop and Brian Coleman’s Check the Technique. One was about hip-hop culture. One was about hip-hop music. But what was missing from that was the business, which to me, was the real story. This stuff didn’t just happen. Run-DMC didn’t just make a record, and it was accepted as brilliant and then they become the godfathers of this shit. No! People had to fight for that. I was there. I was there when Power 106 was playing footsie with hip-hop before they became where hip-hop lives. I was there.

I don’t think I would have had the platform or the standing to write about the birth of hip-hop in the Bronx because I wasn’t there. I had no direct connection to it, but I did have a direct connection to the business. I had a wealth of experience and connections in the business, and I knew the stories. I knew which stories were untold. So, that was the impetus.

A book is an insane thing to do because it’s really a whole bunch of work for no money or a little money when it all comes down to it, especially if you’re going to do it right. So, there always has to be some other motivation, right? And for me, a lot of times it’s like, Yo! We gotta do something about this! That’s my motivation.

Again, another hip-hop thing like, They’re ignoring my man! I’ve seen all this stuff come out about microrhythm and broken beats, and Dilla’s a footnote. Sometimes not even a footnote. We’ve got to do something about this! That’s where it comes from. It just comes from a little indignation and anger. And that’s the thing that keeps you going because writing a book about Dilla, in particular, is oof!

You know. You were right there in the beginning. You were actually there in the beginning, Lara. You were one of the first people I sat down with when I was pretty sure that I was just writing a tiny science book about music. I was not getting too deep into biography. I didn’t think Frank Bush was going to be a major character in this book. That stuff was going to be color.

Work Clean: The Life-Changing Power of Mise-En-Place to Organize Your Life, Work, and Mind, which was published in 2016, was a bit of a deviation from what readers may have expected from you. You’ve shared in past interviews about how you came to be familiar with mise-en-place, but can you share some examples of how you’ve been able to incorporate this practice, which typically refers to kitchen organization and food prep, into your daily life, both personally and professionally?

Dan Charnas: Yeah, I think I mentioned earlier I’m a Virgo, so I’m into systems in the same way that an Aquarian is not into systems. I was working for a large media company running a series of websites, sort of nurturing these baby websites to become what they are today. And the company was not well-run. It was a situation where, it’s a public company, and you have all of these really talented programmers and journalists and people working on the floor. And then you have the senior VPs swanning around looking at the numbers and then trying to make the serfs do what they do.

I was struck by all the waste at this company. And that was the impetus. Nobody’s written a book about mise-en-place? There’s no book about mise-en-place? I couldn’t believe it! We’ve got to do something about this! Right? Same shit. Yo. Yo! We’ve got to do something! So, that’s what started it. And, of course, I used my reporter muscle to do it. I interviewed 150 different chefs, cooks, restaurateurs, chef instructors, and that that was how the book got started.

Do you remember the first time you ever heard J Dilla’s music – when/where?

Dan Charnas: Yeah, I do. I remember hearing, in general, from my friends that J-Swift had left The Pharcyde. And he was integral to their sound. And I remember commiserating with Mike Ross at the time who was the head of Delicious like, “What’s The Pharcyde gonna do now that J-Swift’s gone?” And he said, “Oh, man, don’t worry. We found this kid from Detroit named Jay Dee.” I’m like, Jay Dee? Who’s Jay Dee? Detroit? What hip-hop has come out of Detroit?

I was not the only skeptical person. Ask Brian Cross. He was the same way. “Jay Dee? What?” And then, of course, Delicious threw an album release party at the House of Blues. It was a Pharcyde performance, and we saw the “Runnin’” video and heard the song for the first time. And that was when I knew. Oh, Jay Dee from Detroit. That was when he became Jay Dee from Detroit. That’s how he became one of my favorite producers. I remember the day. I remember the moment.

When did you start to develop your course on Dilla?

Dan Charnas: I first heard him in ‘95 with everybody else. Then, I went to Detroit to work with him in ’99. About a year later, I left the business to write comedy and write for TV. And then I left L.A. in 2004. Literally a month later, he arrives. And what’s weird is his friends were my friends: Rhettmatic, Brian, Babu, C-Minus, Choc. He comes into their world as I’m leaving. And Dilla is just somebody who’s a part of my musical background. I’ve always loved hearing his stuff. But then, in 2006, he died.

In 2005, I actually began to hear his influence move out into the music world in a big way. So, I proposed an article to Scratch Magazine at the time, which Andre Torres was editing. I said, “I want to do an article about this rhythmic signature.” I always felt like Dilla was the source of it. I reached out to Tim Maynor, whom I knew from the record business, the manager of Slum Village, and I said, “I would love to interview Jay Dee.” And he said, “I don’t know, man. He’s almost outta here.” He was home from the hospital, but he was almost out of here.” Wow. So, I never did that interview.

I don’t think I would have taught this class had two things not happened. The first thing is, nine years after I first went up to Detroit to work with him, I went to Detroit again. But this time, it was to meet my girlfriend’s family – the woman who would become my wife. Wendy took me one day and said, “I’m going to take you through Detroit.”

So, over the course of the next decade, Detroit became sort of a second home. At the same time, I’m starting to teach at the Clive Davis Institute where Jason King is like, “You should teach a course on Dilla.” Because so many of our undergrads were into Dilla, inexplicably. His influence was just pervasive. And, at first, I was like, “Oh, well, Questlove should teach it because he teaches here.” But Questlove didn’t have time to do it, I think because of Fallon.

So, I was like, “Alright, I have a Detroit connection. And hey, why don’t we just take everybody to Detroit for a field trip? Let’s just go to Detroit.” So, we did. We went to Detroit. Twenty students and me went to Detroit for three days and met with Phat Kat and RJ and Young RJ and got tours of the west side and the east side. We went to the house on Nevada and McDougall. Waajeed stopped through.

It was all cool, and then we had this amazing course when we returned to New York for seven weeks. And Questlove came by and Bob Power and Dion Liverpool, you know, Rasta Root, and Timothy. Rhett called in. That was the first class in 2017. You were there in 2019 when we finally got Herman, and we finally got Ma Dukes to come. It was a great experience, and it was because of what I was assigning them to read and what didn’t exist. Everybody was talking about, “Oh, Dilla doesn’t quantize.” That’s like saying, Albert Einstein didn’t quantize, and that’s how he came up with E = mc². Come on, man. We gotta do something about this!

How did you decide on the arrangement of the narrative, instruction, and history lessons contained within the pages of Dilla Time: The Life and Afterlife of J Dilla, the Hip-Hop Producer Who Reinvented Rhythm?

Dan Charnas: I think the book definitely evolved out of the course in the sense that when you teach a course on something, if you teach a course on J Dilla, it’s not going to be the guy’s life story or just the guy’s life story, or even primarily the guy’s life story, because you’re teaching about somebody because they’re important. So, what are you teaching when you teach? You’re teaching their work. You’re teaching and you’re deconstructing that work. You’re helping people understand what the innovations are of that work, the influences of that work, maybe what the meaning is or the context of that work. What’s the history of that work in terms of its making? What’s the impact of that work commercially?

I still really appreciate you allowing me to sit in on a couple of your classes a few years ago and remember you sharing with the class about how Dilla took the song “Clair” by Singers Unlimited and “slowed it down so that the word ‘Clair’ sounded uncannily like ‘Player,’” a sample that can be heard in the SV track, “Players” off Fantastic, Vol. 2. How did you choose which, let’s call them, nuggets to include in the book?

Dan Charnas: It’s a good question, because I think they, you and I know Dilla Heads, were like, “Why didn’t you put this song in? One of my favorite remixes by Dilla and most impressive performances of his, is a remix of a Carl Craig produced Innerzone Orchestra song, “People Make the World Go Round.” I don’t know if you’ve ever heard that but Jay Dee’s version of “People Make the World Go Round.” Oh my God! Probably Top Five for me, but I couldn’t find a space to put it in the narrative, and I couldn’t report it. And I couldn’t get Carl Craig. I probably could have gotten him, but I just didn’t. Something gets included if it means something. Something gets included if it explains something.

So, what “Players” and “Clair” explained was this concept of deceleration. He started with one technique, which was playing freehand, but then he developed the second technique, which is deceleration, pretty close thereafter. I think he was doing both at the same time, actually, but the idea of slowing a sample source down to reveal error and then putting this one slowed sample source against another slowed sample source and watching the mess that ensues.

Until very recently, I had only read about or seen accounts of Dilla working on an SP-1200, not the AKAI MPC that’s mentioned multiple times throughout the book. Why do you think his name is associated more with the SP, like the vinyl figure and the “King Of Beats” box set?

Dan Charnas: Right! Cause people don’t know shit. And, I’m being very honest, it was a revelation to me, too. But then it made sense because I guess one of the things that I realized that I didn’t know in 2019 when you came to the class, or maybe I did at that point. Maybe I should give myself a little more credit. Somewhere between 2017 and 2019, I realized that Jay Dee’s beatmaking techniques didn’t arrive fully formed. They evolved.

And the thing I believe that people do not talk about is how his beats changed when he started using the MPC because everybody knew in the beginning, he was using the SP-1200. And not even his! He was using Head’s. He was using RJ’s. RJ was like, “Yeah, he borrowed my drum machine and never gave it back.” It’s just very funny to me but also indicative of the kind of person RJ is, sort of a generous, if somewhat skeptical, mentor.

You can hear some time in ’97 or ’98, not only does the sound quality of the samples change, but he begins to use things like independent swing and shift timing. I’ve never talked about this with anyone before, but I tried to pinpoint when that was. Like, the “Sometimes” remix, which came out in ’97, I don’t know if that was an MPC beat or not because none of the elements in it are offset or shifted. It doesn’t seem to me to be. And I know that’s 1997 because it came out in 1997.

But Another Batch, that beat tape, which is the beat tape I got before I went to Detroit that first time. That came out sometime in 1998, and that has some notes shifted all over the place, shifted and swung. I know that had to be the MPC. One of the things that I wish I had a little bit more authoritative word on was the biography of his equipment. When he used what and what machines he was using and who owned them.

Dilla became very aware of those around him trying to emulate and/or copy his signature style and sound. You mention that he “didn’t know that he wasn’t simply a beatmaker, nor did he grasp how big of an idea he had cultivated” just over halfway through the book. In your opinion, do you think he understood the impact he’d made on hip-hop before his passing, even if he was still largely unknown up to that point?

Dan Charnas: One thing I would never claim is to know what James was thinking unless he said it. I feel like he knew he was influential, definitely. You can hear in those interviews in January 2003, he’s talking about it. He knew he was influential, and he was just perturbed by it because real hip-hop, you do your own shit. But he didn’t realize that it wasn’t just a style that he had invented. I don’t think there was anybody around him, nor he himself, who could have articulated exactly what it is that he did. Because you know, Lara, nobody has done it until now, right? I know that’s a bit of a flex.

I fully support that flex.

Dan Charnas: You know what I’m saying? Who could have told James that? Nobody. They could tell him he was great, king of the beats, the best, better than Dre. Whatever. It doesn’t mean anything. He created an entirely new rhythmic feel. He didn’t care. My sense is, I don’t believe he cared at the very end. I think he was onto the next. I think he was trying to fuck with everybody, like trying to fuck with Kanye, trying to do things that moved him, that made him feel good.

Maybe, and this is just me guessing, I think a little sense of acceleration for him. There is one point in the prose where I say, “Break the records, break them all.” And I just hear James sampling in 2004/2005, and I just see him taking a sledgehammer to these records, accelerating through them, masticating them, breaking them down to even smaller and smaller compounds to make his compositions.

Accounts of important moments in time are weaved beautifully throughout the book, including that of Miguel Atwood-Ferguson’s Suite for Ma Dukes event in 2009, as well as the Dilla Day Detroit where a state senator honored Ma Dukes proclaiming February 10th Dilla Day. What was it like hearing first-hand accounts like these in the more than two hundred interviews you conducted during four years of research and reporting?

Dan Charnas: It was great, especially the performance of Suite for Ma Dukes, and that’s one of those things where it’s like, Man, I wish I had known. I wish I had been there. February 2009, where was I? I remember Obama had just been inaugurated, and my wife was deeply pregnant, and I was about to be married. So, I don’t know if I would have ever been able to make it out there.

And I guess the sweetness of it is, I am blessed that we have had a bit of a history in the business and that these are my friends who did this. So, even though I wasn’t there, and I had nothing to do with it, it’s nice to know my friends were there.