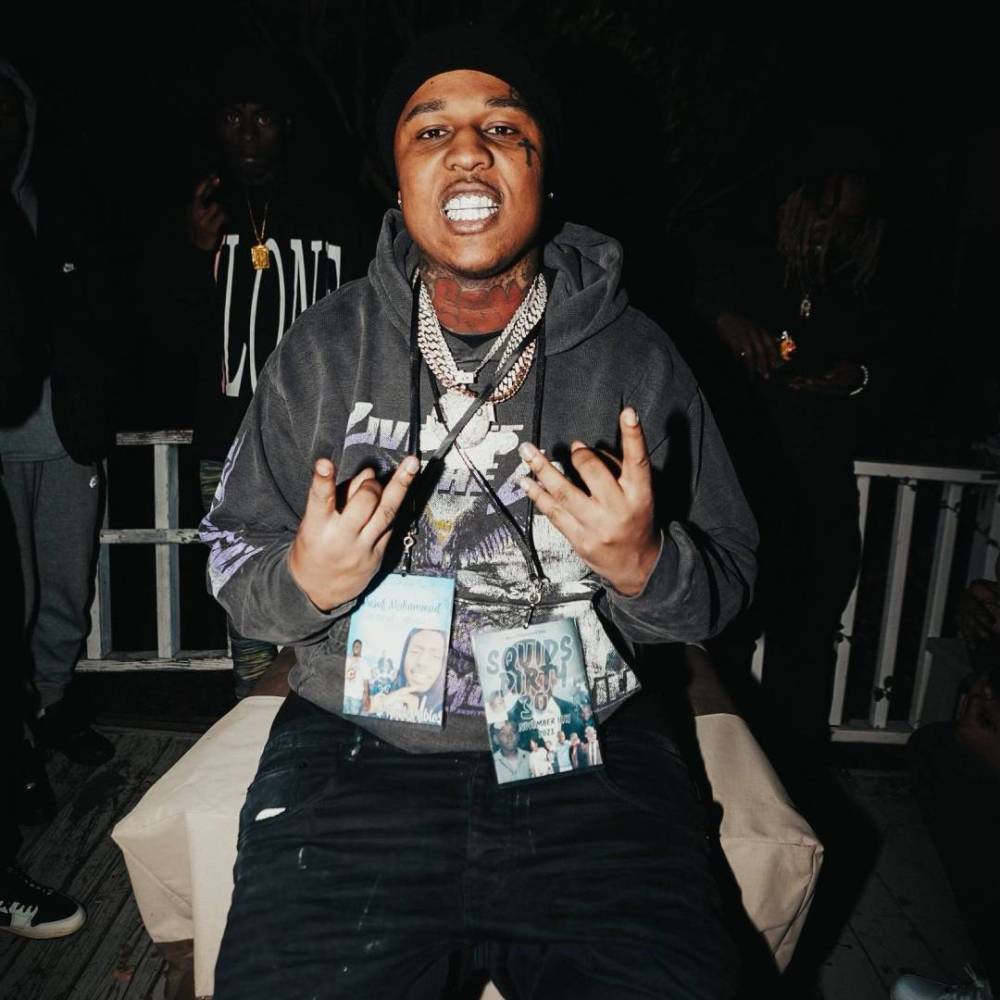

Image via Ramal Brown

Steven Louis will not migrate Slack to Teams, he has no idea what any of those words mean.

The hottest breakthrough rap act in California is once again locked up. This is the first time that EBK Jaaybo has been charged as an adult. It’s also the first time that he’s been incarcerated with a charting single to his name. But everything else is numbingly, perversely par for the course.

The arrests began when he was 14 years old. A series of gun and burglary charges first sent him into perdition, a punitive sentence for a child mired in poverty and grappling with the murder of his father. At 21, Jaymani Gorman is now serving his seventh stint behind bars. He’s developed a routine, the self-described “dance moves” to cope with confinement. Once again, lyrics and video stills are in a California rapper’s case discovery files. Jaaybo has dealt with California’s gang enhancement penal code so many times that he can recite it word for word. To paraphrase another historically great rapper ensnared in the state’s cycles of bloodlust and jealousy: it’s regular but it’s definitely not normal.

EBK Jaaybo is the consummate artist for a country undergirded by violence and a society starved for unvarnished truth. He hails from Stockton, once the owner of the nation’s highest foreclosure rate and still the largest American city to declare bankruptcy. He is the human incarnation of Omar Little in the courtroom, rendering a shotgun and a briefcase as functionally indistinguishable. He’s one of the sharpest and most thrilling rappers alive right now, yet unlike most of his caliber, he seldom raps about his own rhyming prowess. Syllables get drawn out with snide enunciation before collapsing into frigidity and superboosted bass.

On “Apocalypse,” one of his first hits, Jaaybo puts together “Glock lifter,” “shot sender” and “mob member” with the attentive aggression of a gangland kingpin trying to teach stage direction. Schemes are tripled up with careful density before being unceremoniously dropped for a new, equally tangled rhyme. It’s gruff and chaotic, AAA/B cadences that feel like prime Steve Francis contorting to finish a self alley oop over the opposing center.

His breakout hit “Boogieman” is a singular oddity for viral music, one of the most unlikely social media smashes of this generation. The pressurized bass damn near rattles a phone screen, synching on the down beat with borderline arhythmic key smashing. It’s blemished jet-black anti-pop, a gladiator’s theme for the year 2100, with Jaaybo “dropping bangers with no hooks again”. Somehow, it has reached the “hot women doing choreographed dances” part of TikTok.

Jaaybo’s mushrooming popularity belies the music’s cruelty and vitriol. The opps are not faceless; in fact, entire songs like “Fly Exterminator” and “Had Enough” are smirking, blood-soaked dedications to a Stockton rival set. Some songs, like the searing emo banger anthem “Do Not Disturb,” are compression chambers for pain and trauma. Others, like the Beabadoobee-sampling “Death Bedz,” feel like reconciling with broken pride – “they say I’m valuable but move like I ain’t worth a cent”. It stings every replay.

The latest project, a 21-track collection called The Reaper, is mostly what he calls “straight-up street shit.” He’s aware that this energy works counterclockwise to his rehabilitation efforts, but he seems content to let his listeners sort out the contradictions and the discomfiting intersections. The motifs are strange and unique if not chillingly hyper-specific. Jaaybo loves firearm switches and vector clip magazines, he’s spinning like a tornado and eliminating rivals with a fly swatter. The ski masks are still on the ground. Conspicuous silences in the middle of verses still create gaps for things left unsaid. There are no features here, just raw and unforgiving menace.

We connected with Jaaybo from San Joaquin County Jail, where he gave his first official interview since going back down for illegal firearm possession by a felon in January. The night before his 21st birthday, Jaaybo spoke with righteous defiance and a hardened familiarity with solitude. Again, no part of the carceral experience is new to him. But Jaaybo shares a clear and motivated vision of what his future holds. Jaaybo sees a mansion for his kids to grow up in, far away from Stockton; they’ll never know what their father’s Nightingale block looks like, or how it feels to have their heads on perpetual swivel.

He reveals that he’ll be back home in four months, with plans to tour and make new music. He says that he misses his fallen soldiers and his father Rary, but no longer believes that physical presence is the measure of company. As he sees it, he’s never going to “die by the gun,” but he also doesn’t think he’s living by it any longer.

(This interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.)