Support truly independent journalism by subscribing to Passion of the Weiss on Patreon.

Abe Beame‘s sartorial spirit guide is Billy Crystal in Throw Momma from the Train.

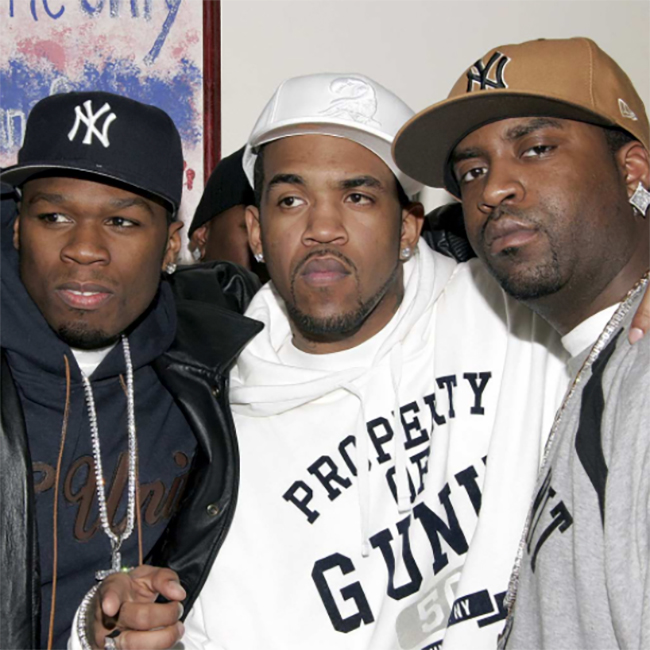

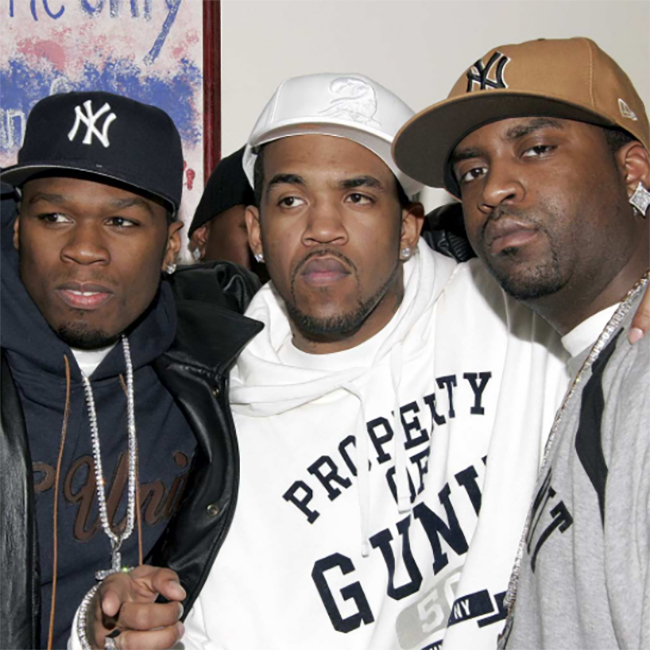

There are other contenders, but if you’re looking for a collective that defined the first decade of this century in rap, it’s really G-Unit. The very appropriately christened Guerilla Unit has expanded and retracted countless times, but at its core, was composed of 50 Cent, Lloyd Banks, Tony Yayo, The Game, and Young Buck.

It starta with 50, an industry outcast who had to fight for his physical and professional life after his first, shelved, unheralded classic, Power of the Dollar. With a song called “How To Rob,” he succeeded in alienating the entire rap industry, finding himself a man without country while recovering from an infamous shooting he was incredibly fortunate to survive.

His solution was to highack the mixtape, a barbershop currency rappers up to this point dabbled in to keep their names buzzing. He would do favors for local New York DJs, work out new material, and reimagine the mixtape as a way to build mythology, gather an army and return to storm the city. He made his own albums, created a brand, and eventually that brand translated to a feeding frenzy that held rap hostage, made him a millionaire, and literally remixed the entire music industry. It was the consummate New York hustler’s approach to a problem.

Exactly 20 years ago, G-Unit released 50 Cent is the Future, No Mercy, No Fear, and God’s Plan between the summer and fall of 2002. This was a time before artists were believed to be capable of this type of manic prolificacy. When Jay-Z would spend a year working on a painstakingly curated, 12 song “masterpiece” that was very much in the vein of what still dominant rockist critics believed true artistry looked like. G-Unit trashed that idea and heralded a new age of content churn that would come to define rap music and what was expected from its ascendent rappers.

The early G-Unit mixtapes were acts of open rebellion. The world turned its back on 50 Cent, so he turned his back on the world. It wasn’t just in his refusal to play the game and wait for a label to recognize his talent and come calling, it was the actual material that populated the mixtapes that brought him back to prominence. 50 would appropriate the most saccharine hits clogging the airwaves in this era of congenial, fluffy, “106 & Park” pop, dominated by the likes of Nelly and Ja Rule, and make songs that winked at, and gave the finger to its source material.

The use of beats, going back as far as the inception of riddims in dancehall, were opportunities for artists to get on popular grooves and prove their mettle. By the time we get to mixtape rap circa 2000, this meant spitting a 16 over the beat that was currently dominating the airwaves. As soon as something vicious from Timbaland, Pharrell, Just Blaze, or Preemo would drop during this period, there would be a Meadowlands parking lot port-a-potty line stretched far as the eye can see, of rappers eager to put their stamp on it, like graffiti writers waiting to get their cans on a clean train.

But 50 reconceived the merit of this concept. He didn’t settle for solid bars over familiar beats. He made entire elicit, thematic songs that specifically, brilliantly subverted their meanings. He made fun of their frivolities with truth to power equal parts fun and grimy shit. What made it cogent, and visceral was his talent. He was always a great songwriter, and all the sarcastic commentary aside, encapsulated in his incendiary critique were earworms better than the pop he was spitting over. He was the snarky, funny Queens asshole the industry needed to point out how corny and soft the game had become.

Eventually, 50 took the money. Of course he did. He pioneered an end game, boss stage vision of capitalist rap that untethered the idea of artistry, personality and perspective from the rap album and turned it into a game of crowd sourced, something for everyone power pop that presaged the streaming era. G-Unit foreshadowed the death of regionalism, of rap moving from boroughs and states and coasts to the internet. 50 was a guy from New York who famously sounded Southern, then seamlessly folded in The Game, a Compton claiming Pac disciple with a taste for soul samples, and Young Buck, a coke rapper from Nashville with the voice and bearing of an old soul, fire and brimstone preacher. 50 didn’t care, it just broadened his mass appeal and market share. Curtis was always in it for the money. That was his entire perspective, his hook, and why he resonated on a gut level with a Bush era, cynical and worn out millennial clientele.

But the early, and even later aughts G-Unit mixtapes serve as a kind of postmodern CBGB. A time when a folk hero went electric and showed the world there was a better, weirder, dirtier way to reach the hearts and minds and wallets of the American youth. Today, he’s a Shonda Rhimes like maven for the same public that lapped up The Massacre, but if your fingers are dexterous and your memory is sharp, there’s an entire secret history on YouTube of the man, and the band, that knocked the world on its ass for a brief, strange, beautiful moment in time.

20. Got Me A Bottle (50 Cent is the Future, 2002):

As will be the case for many of the entries on this list, context is essential here. The source material for this remix, R&B singer RL’s “Got Me A Model” (featuring Erick Sermon at a weird moment when I’d assume E Double was paying for the privilege of getting featured seemingly everywhere as a rapper), is a strummy, sexy, very 2002ish Jermaine Dupri production, firmly in his Puffy aping, Don Chi Chi era.

It’s a lavish, satin pillow, vaseline lens shmeared, aspirational shiny suit jam about hooking up with an expensive beauty in the velvet rope cordoned section of a shitty club. G-Unit provides a direct and immediate corrective. The focus is shifted from the paramor to the lubricant, and the specific brands are instructive. G-Unit is sipping on Smirnoff, Absolut, Tanqueray, Henny, E&J, brands you can find in airplane bottle sizes at a local liquor store rather than the Astor Place boutique shit other rappers and singers might’ve been bragging about sipping on circa this era.

Banks’ verse captures the vibe, that hooking up is secondary to getting bent, that he could hit or not, he won’t be pressed and it won’t make or break his evening. This cold eyed clarity, the lack of romanticism and embellishment, was a breath of fresh air, a dousing of cold water, rinsing the faces of a public that had spent years listening to penthouse luxury catalogue raps.

19. I’m So Sorry (G-Unit Radio Pt. 5: All Eyez On Us, 2004):

An interesting wrinkle of the G-Unit group dynamic on these mixtapes is there aren’t a ton of songs that assembled the whole squad. It was always features and side missions, with some members carrying the bulk of entire G-Unit Radio installments. I wanted to include a track that got the whole squad together (minus Yayo) to show why that might have been a conscious decision on 50 or Whoo Kid’s part. The song, spitting over Anthony Hamilton’s somber “Since I Seen’t You” (Another hilarious wrinkle is G-Unit really loved Anthony Hamilton beats during this period, I think they rapped over three or four of his tracks) is good, and so are each of its individual parts, but they don’t really hang together as a cohesive whole. Each rapper takes their verse and makes the song their own thing.

It’s the antithesis of a collective like Wu-Tang, perhaps because Wu-Tang wasn’t a collective, they were a group. G-Unit always had the feel of free agent mercenaries that came together for a short period of time to win two championships, then peel off and do their own thing.

18. Gangsta’d Up (God’s Plan, 2002):

A great 50 hook, jacking Butch Cassidy’s bridge rather than Snoop’s proper hook on the Eastsidaz exemplary piece of late 90s G-funk, “G’d Up” and improving on it. The verses are brief, and explain why Yayo and Banks were such good sidekicks for 50, both contained elements of what 50 brought to the table as a total package MC. Yayo was funny and personable, Banks witty and viscous. 50 contained these multitudes, and complimented his skills with an incredible gift for melody, which neither Banks, Yayo, and most pop artists in the history of music have been capable of.

So Yayo’s verse is typically meathead with a few dumb/funny punchlines, Banks is sharp with his metaphors, and 50 does a kind of stock, Dickensian, abbreviated verse. But this track earns its position because of its sign off, by 50, delivered on the night his “friend” but really his mentor, Run DMC legend Jam Master Jay died. 50 acknowledges how brief the track was, and does an admirable job hiding his emotions, but the lack of humor, the straightforward acknowledgment of the tragedy, and giving his condolences to Jay’s family, strikes a melancholy chord for me every time.

This was part of the magic of the early G-Unit tapes. Through these little asides, the intros and outros, the humor, the ad libs, moments that live in the margins of traditional songs, in songs that could go from the booth to the street in a matter of hours, that could address current events in real time with the immediacy of diary entries in a way the glacial months, if not years long process of getting a major label release ready for public consumption ever could, 50 at least conveyed an intimate and knowable presence on these tapes. It had a lot to do with why the fanbase he cultivated pre Get Rich Or Die Tryin’ was so rabid, what made him a commodity so precious it sparked an industry wide bidding war, he created a character on these mixtapes we all invested in, and wanted to see win.

17. You’re Not Ready (God’s Plan, 2002)

In which G-Unit goes over Beanie Siegel’s classic, “The Truth”. This easily could’ve been on Get Rich or Die Tryin’. The tone matches the sneering street anthem model that accounts for most of the album tracks on 50s platinum, game changing effort.

What I like about it is Beanie’s song was two years old at this point. While much of this list is 50 highjacking the pop rap hits of the day and spoofing them like Leslie Nielsen, his mixtapes were also less obvious acts of selection and curation, where they’d make brand new songs that bore little to no resemblance to their source material. The collective went with Beanie Sigel’s eponymous track here because they just fucked with the beat and wanted to leave their mark on it.

It’s also a pretty textbook exhibition of the G-Unit dynamic: 50 with a titanic hook and conversational witty dickhead verse, Yayo with a brief cameo, dancing and making his presence felt, and Banks showing up like Mariano, spitting technically accomplished, pristine 2000s era New York mixtape crack, full of “Damn son” rapid fire punchlines.

16. It Is What It Is (G-Unit Radio 2: International Ballers, 2003)

Something inseparable from the rise of 50 and G-Unit was the beef with Ja Rule. It was an all timer, one that kept the entire culture riveted and kept pulling in more and more of rap’s notable figures on the periphery. It seemed like everyone had to choose a side at some point. Coming in, we thought it was a David vs. Goliath contest, with 50 as an indie little guy going head to head with Ja, another kid from Queens who literally ruled the airwaves at a time when that still really mattered. As it turned out, it was a David vs. Goliath contest, but we had the roles reversed.

Ja leaned so far into making mainstream saltwater taffy with the likes of Ashanti, he’d lost his cred, and his edge. He’s like Rocky in Rocky IV, high off his own gas, eating cheeseburgers being served by his robot waiter with his feet up in his mansion. 50 was out in the woods, in the snow, dragging trees uphill, primed to come out and eviscerate Murda Inc.. He exposed them for the butter soft, rap and bullshit schlock merchants they were.

The best G-Unit diss is “I Smell Pussy” off 2003’s Beg for Mercy, a song that uses a child’s music box loop as a trojan horse to smuggle in absolute savagery spit against Ja, Irv, and company, but it’s not a remix, so it doesn’t qualify here. I opted to go with this brief flip of Talib Kweli’s dramatic Kanye produced single “Get By.”

50 spits roughly thirty seconds of actual bars, but it’s my second favorite Ja Rule diss because it highlights the fun of G-Unit mixtapes: 50 vamping. His little bits, casually tossed off jokes and asides were very much a part of the experience of listening to these mixtapes.

He was a large, outsized presence on the mic, both offbeat and on. 50 gets some good, detail rich specifics into his bars here. I particularly like the little digression where he pulls up just shy of doxing Ja, but I absolutely love the laugh out loud moment after the verse when he drops into a Ja impression and becomes a full blown music critic, clowning Ja by concisely summing up his entire style, crumpling it in a ball and throwing in the trash at 1:40. 50 not only does a spot on Ja hook (he seems to be interpolating “Mesmerize”), but by calling them fast food jingles, he accurately assess their fatty and disposable commerciality, that Ja has gotten into the business of making products rather than keeping it real. Then he goes at Ashanti’s neck. 50 was the Joker. Nothing was sacred to this man. Love 50 or hate him, it’s very, very difficult to quibble with his genius.

15. 200 Bars (G-Unit Radio Part 8: The Fifth Element, 2004)

Enter The Game. One of the more fascinating MCs from this period, a Compton MC who desperately needed to let you know he was from Compton, one of the few rappers I would credibly describe as a “gangsta try hard”. It’s in his name, “The Game” was a kind of hood historian, a rapper dedicated, and steeped in the past of rap itself. This was an era where Jay quoting Big in his raps was controversial, Game made an entire style out of quoting classic rap and name checking great rappers, along with albums, songs, moments that litter their histories. It was alternately corny and fearless, yielding interesting results most notably on his debut The Documentary, which might be the “most perfect” G-Unit solo album in its incredible beat selection, (50’s included, yes I said it) if not the best.

This track is a nine minute slog over, what else, “Deep Cover”, a kind of participation trophy effort that wants credit for being nine minutes long, but is littered with mostly forgettable bars, and some interesting nuggets of reference. What the track displays is Game was a particularly apt choice for G-Unit, a postmodern rapper in a group built on reference and subversion. “200 Bars” is here because it so perfectly articulates the full court Game experience, the giddy highs of his rap historian approach, and the insipid lows of his high volume, bar filling, unimaginative and aimless tough talk.

14. G-Unit- E.M.S. (No Mercy, No Fear, 2002)

G-Unit remixes “The Blast”, a snapshot of a time and place in backpack rap Talib Kweli made with DJ Hi-Tek on their group Reflection Eternal’s Train Of Thought. This in and of itself is a pretty cool idea for a crack and guns South Jamaica mixtape rapper to use as a sample, but the degree of difficulty is amplified by the fact that the beat literally has Kweli’s NAME repeated throughout it. 50 leans into the hurdle, using homophones that closely mirror Kweli’s name on his punchlines. Just brilliant, hilarious shit.

13. Just a Touch (Back To Business: G-Unit Radio 14, 2005)

50 always had impeccable taste when it came to picking beats to remix. He had a knack for zigging, with the obvious, enormous pop songs of the moment he knew his fans wanted to hear him over, but he also could zag, approaching curation with the discerning eye of a seasoned crate digger.

“Just a Touch” is case and point, a song that remixed Mobb Deep’s collab with the street legend Kool G Rap, “The Realest”, six years after it was released on 1999’s Murda Muzik. The original is the kind of Carhartt and leathers, sneering mean mug affair that would’ve played at a Queensbridge afters seconds before a drunk guy without eyes on his six got robbed.

But 50 identified the molten chocolate core of the sample, Alchemist’s sped up flip of Ecstasy, Passion and Pain’s “Born to Lose You” from 1974, and made something different. A song that blurs the line between rap and R&B, something hedonistic and illicit, that anticipates the era of 808s Kanye, the Weeknd, and Drake. It’s a fucked up and callous song that didn’t remix the original as much as it was rewritten and reconceived, but it didn’t prevent it from becoming a full blown hit on its own merits when 50 pulled Paul Wall, at his Houston Renaissance apex, onto a remix.

It’s an example of 50 remaking the world. This was post Get Rich or Die Tryin’, 50 could manifest whatever he wanted because he was the king. Mobb Deep was actually signed to G-Unit records at the time, presumably making rights to the production a formality. So it isn’t quite the miracle another G-Unit concept made flesh would be down the line, but it’s still a pretty remarkable act of songwriting and hit making, flipping a Mobb Deep song on their own beat into something that became much bigger, a feat made look routine throughout this period.

12. Afta my Cheddar (No Mercy, No Fear, 2002)

Who knows how much the God of Farmers Boulevard shelled out for this late career visible abs and B-cup pecs hit from the Neptunes, but 50 made a better song out of it for free. There’s a few things I love about it that we need to call attention to.

50 peppers the hook with this little rhythmic ad-lib/phrase “You want that money right?” and it’s note perfect. Keep in mind this is 2002, just before guys like Jeezy and Ross would turn the ad lib into its own essential element in every rapper’s toolbox, and 50 at least deserves some credit for that. He always seemed to know where the soft and fleshy parts of the melody were to fill and flex on, and this is probably my favorite example of that, in an instance where it actually contributes something essential to the hook that Pharrell didn’t find.

And then there’s the joy of 50’s crooning. Wonderfully, emphatically off key and just going for it, and it really works! And of course, in classic 50 fashion, he ends the song acknowledging the bug and making it a feature. “Bitch I’m Luther Vandross in the shower!” has to be one of his greatest laugh lines and joke deliveries in a career full of classics.

11. I Love The Hood (G-Unit Radio 7: King of New York, 2004)

A showcase for peak performance Game and Buck over Nas’ Lost Tapes 70s strings dripping classic, “Poppa Was a Playa”. Hard to understate how disastrous Game and Buck could’ve been as additions to the collective, and instead cemented the group’s legacy on a national scale, as well as the brief reputation 50 had as an elite talent scout. G-Unit were the Goodfellas, three intensely Queens guys who wore New York as a brand and shield at a time our market hadn’t yet fully embraced regional rap, but as discussed above, and a bit more below, 50 was savvy with his choices, and he made Buck and Game stars in their own right.

“I Love the Hood” is the kind of “album track” gem that was routine when burning through a new G-Unit Radio. There’s no event level hook from 50, it’s not a beat that makes you immediately sit up, eager to see what these rebel sickos will do with America’s latest pop flavor of the month. It’s one for the fans, it reminds you even after the meteoric rise, after the nine figure bidding war and ten figure albums sold, these releases still had to work as mixtapes. Raw rap over hard production, with Buck spitting muddy, triple beam poetry and Game in double time dropping Joe Budden and Shyne references. It’s the platonic ideal of that elemental mixtape concept.

10. Doing My Own Thing (Automatic Gunfire, 2003)

A pretty incredible artifact, in which 50 plucks the grown and sexy 1995 pre neo-soul coffee shop hit “Tell Me” by one hit wonder Groove Theory, and makes a kind of mission statement anthem declaring his independence.

Narrative interpretations aside, it’s just a great song. The hook borrows heavily from the original with 50 fully singing his heart out, but it’s one of the rare occasions he doesn’t use a cadence mapped out by the original MC in his verse, because he can’t, there isn’t one, it’s R&B. He really puts some sauce into syllable packed, rapid fire bars, and sounds like he’s having a great time throughout. As enjoyable as it is surprising.

Much like “E.M.S.” above, this was one of those “I didn’t know you could do that” moments. Guys were still rapping over Milkbone’s “Keep It Real”, Mobb Deep’s “Shook Ones pt. 2”, and Delinquent Habits; “Western Ways pt. 2”, and here comes 50 rapping over some shit my mom used to turn up when it came on the adult contemporary radio station in her Plymouth Voyager.

9. 50/Banks (50 Cent Is The Future, 2002)

Again, just a wild expansion of the capabilities of a mixtape freestyle. It’s a G-Unit remix of Bubba Sparxxx and Jadakiss’ “They Ain’t Ready”, a phenomenally intricate, in his prime Timbaland beat off Ruff Ryders: Ride or Die Vol. III. But 50 uses it as an opportunity to comment on the state of the industry, and share a little inside baseball with his audience, explaining the thought process that goes into dropping $100,000 for a beat from a super producer like Tim, and somewhat facetiously questioning if he’s ready to make a leap like that in his career.

I say facetiously because he clearly was. The hook is as funny as it is catchy, and both he and Banks are on top of their games here, turning the beat into a song as good if not better than the Jada and Sparxxx classic. And, as we’ll see a bit further down this list, within a few months 50 had manifested, spoken his truth into existence with a proper remix of a Timbaland beat that would serve as a return to prominence, his coronation as something more than an underground phenomenon.

8. Short Stay (God’s Plan, 2002)

Another in the milieu of 50 bringing his specific South Jamaica slant to a beloved pop hit. This one is particularly delicious because it was former Hot 97 radio deity Angie Martinez’s one big hit during her foray across the aisle as a rapper. Angie’s flossy, literally escapist version, “If I Could Go” (made with R&B singer Lil Mo and Jay-Z/Grafh impersonator Sacario, two other curios of this era in New York radio rap), is about absconding, presumably to a romance language speaking Caribbean island, for a weekend jaunt. Just rich people vampling and flexing about a very specific luxury their life affords them.

50 flips the hook into a (great) song about taking a woman he’s having an affair with to a motel near an airport for four hours of fucking. Just a devastating, Armond White level critique of how frivolous and absurd this beach cabana, tinted sunglass rap really is, and how comparably savvy and spendthrift 50 is. The subtext: You don’t have to pay for an overseas flight when you’re laying pipe properly, and all these assholes who brag about spending exorbitant sums to get the same thing are lames.

7. Fat Bitch (No Mercy, No Fear, 2002)

A hilarious song as well as an exercise in narrative building and myth making for Yayo. “Fat Bitch” sort of reminds me of Brit pop teenie bop mags, or the boy band revival in the late 90s, where every member of the featured group gets a backstory (The bad boy, the sensitive guy, the….. sporty spice? etc.) Here, it’s setting up Yayo as a man with a predilection for plus sized women.

You could argue that these days, a song like “Fat Bitch” needs to come with a trigger warning, but here’s the thing: it was wildly inappropriate then too. It’s a remix of De La Soul’s body positivity anthem “Baby Fat”, which fit firmly in the milieu of the headwrap, sandalwood incense, and leather thong sandal rap of the Rawkus/Soulquarian/Dead Prez hive in 2001-2002. 50 is very strategically and specifically skewering that. 50 and Banks’ verses are hilariously pitched like a Reggie Warrington set, full of punchlines that make fun of their would be plus sized paramours. It all feeds into 50’s persona during this era, and probably even now, a funny asshole and bully who doesn’t feel the need to play by industry rules or bow to conventional wisdom. Love him or hate him for it, you’re reacting, which means it works.

6. 6 Bricks Left (Welcome to the Hood, 2004)

A classic Buck solo. I’ll tip my hand here and admit that Buck was always my favorite. This was the era of Jeezy and Ross types, when rap was about making escalating, increasingly outlandish brags and boasts about how much money you made and how many drugs you sold. Buck presented a diametrically opposed vision of the hustle. He was clearly a street level, retail guy, and he reflected that in his working class raps. As an economist he was about pragmatism, selling at a fair price, if not a discount to attract volume. Not about getting the largest sale, but the most sales. He wasn’t about flashing his money, but keeping it, and staying out of prison for as long as possible.

“6 Bricks Left” is a kind of world weary hustler’s prayer, oddly sweet and hopeful, quoting his hero Tupac in his desire to just get rid of the work he has on him, get clean, and go home. It’s also an example of something G-Unit remixes did for me that is difficult to articulate. I’ve heard Pac’s “Check Out Time”, an anthem about getting out of dodge after a night of debauchery, millions of times, but there’s something softening in Buck’s use of the exact same song.

When you listen to the beat riding out at the end of the track, you can almost see his truck, cautiously speeding no more than 10 miles over the speed limit, down a highway, beneath a slowly rising crane shot, as Buck drives away from danger and menace, and off into a sun setting slowly over Tennessee. It’s a beautiful character sketch, a work of philosophy, giving us a proper introduction to a rapper who would write a crucial chapter in G-Unit’s history.

5. Banks Victory (No Mercy, No Fear, 2002)

With the possible exception of Method Man, I’m not sure if there’s been a king of New York who’s legacy has been more or less forgotten, if not outright written out of history, like Lloyd Banks. For several entire years, he was the city’s punchline king, and absolutely has to go down as wielding one of the sharpest pens the mixtape game has ever seen.

There’s a chance these next two entries on this list are his masterpieces. They’re iconic, star making turns that blew out many a CD-R and the car speakers they were playing through 20 years ago.

50 does an admirable Puff impression here, quoting his verse on his best song and giving it the 3% treatment as the horns and anticipation build in the same way it did for Big five years earlier. Banks doesn’t have Biggie’s voice, or command, or economy of word and thought, because no rapper before or since has had that, but he does have an endless, inexhaustible supply of fucking bars, and it feels like he emptied an entire notebook on this one.

Banks has an interesting register, it’s thin and eternally horse, but he hits his punches with something akin to a scoff, he breaks his voice in a way that sounds borderline pubescent and works as a laugh, or a punctuation. Fab would use the same trick occasionally, arguably the only other punchline artist of this era who could give Banks a run for his money (I’d also accept Jadakiss) but I associate it primarily with Banks, and it puts you in the mindset of a kid on the train absolutely roasting your ass in a lowkey, non-committal, near monotone manner that is intensely and ineffably New York, and more devastating by its nonchalance. It simultaneously communicates Banks’ incredulousness that you or anyone would have the audacity to fuck with him, his mirth thinking about how lame and weak you are, his complete and total confidence in his abilities. It’s nothing short of a miracle of delivery.

And how can every single bar of a two and a half minute verse be quotable? These punchlines are seared into my brain, forever. I remember them like I remember snippets of dialogue from The Godfather. It wasn’t just the metaphors, he could play seamlessly with tempo, jumping in and out of run-on double-time, his schemes were intricate blueprints, internal and multisyllabic architecture that went beyond what any rapper outside of Cam and Jewelz were even attempting at the time.

Anything works as a call out, but I’ll arbitrarily go with his dizzying Escher: “N***** love to hate you, or love you when you disappear/Catch me on a boat with weed smoke in fishing gear/Heavy when I tote, C-Notes from different years/Bezzy and the rope, remotes and liftin chairs.” And then you factor in 50 playing hype man, spicing the bars and plugging batteries in backs along with Whoo Kid, the overall effect was electric. It was Magic filling in for Kareem at center in the finals. An instant classic.

4. The Banks Workout (50 Cent is the Future, 2002)

A very tough call between this and “Victory”, I give this the nod because it’s a tour de force, as a feat of sheer endurance it’s impressive (even if he punched, which I doubt) and there’s something about the cascading drums of “Breathe Easy (Lyrical Exercise)” that makes each punch land like a fucking sledgehammer.

I’m not going to repeat all the Banks thoughts I left above, but I’ll say “Workout” also captures the anti-hero narrative of G-Unit. There’s just something a touch more knowingly sinister and totally comfortable in that evil here. These are desperation bars, you feel this was very much the product of a grimy Queens dude who will do whatever it takes to succeed, and that encapsulates what the G-Unit vibe was during this period, before 50 essentially became his mortal enemy Ja Rule with songs like “21 Questions”.

3. Mind Playin Tricks (God’s Plan, 2002)

This probably seems high for a Yayo solo, but consider this first person account of 50 getting shot as a triumph of approach rather than the material quality of the song. I’ll take a risk here and get specific and personal for a moment on this generic clickbait listicle. The last year has been an exercise in accepting the realities of saying goodbye to artists, to people we love, taken suddenly, senselessly, and tragically. It happened over and over again, with numbing consistency in 2021, and whenever it happens I personally have the same exact response. I don’t want to believe it. I wait, I yell at people who jump the gun in posting about the person in question being dead, I fight against reality.

In terms of skill, I’d have to put Yayo at the bottom of the G-Unit depth chart, but he was what I like to refer to as a personality rapper, in the tradition of guys like Cappadonna, Jim Jones and Sheek, guys who may lack a certain technical proficiency, but win you over with charisma and humor. Tony was the “beneficiary” of what became one of the great street level protest campaigns of the early aughts, “Free Yayo”, which was equal parts a plea to get Tony out of jail after getting hit with a weapons charge in December of 2002, a kind of validation of 50 and G-Unit’s authenticity, and a pun that spawned an entire line of bootleg merchandise en vogue on New York City’s corners and SUNY college campuses throughout the state in 2003.

And this track wouldn’t do much to dissuade you of that. It’s Yayo, in a Ray Liotta voiceover, going through his mundane day, his thoughts and feelings when he heard his friend was shot. But it still connects on a human level rare for a random mixtape track. What I love about this song is it does the best job getting at an idea I’ve been trying to connect to this entire list. What made G-Unit important, not just as rappers but as artists who changed the way I, and many others thought about the utility of the mixtape, and beat curation on those mixtapes, is they were willing to go further afield, to think about the song they were putting together, and were comfortable crossing genres and eras to find the best beat to communicate their message.

Here, Tony Yayo is spitting over what was an 11 year old song about delusion and surreality from a rap group out of Houston. The remix takes advantage of your relationship to the original, and suggests the kind of disbelief I described above when I would first hear someone I admired or loved might be gone. And this was the genius. Attribute it to 50, or Whoo Kid, or the whole collective, but it transformed a song like this into a four dimensional text via production. It’s not just a floor to rap over, it’s a curated experience, preying on our history with the beat, the Geto Boys, the song. This all seems obvious and commonplace now, but it was revolutionary at the time.

2. Work It Remix (God’s Plan, 2002)

A true “you had to be there” moment. In New York, we get one or two of these a generation, because we tend to be slightly ahead of the pitch when it comes to some trends that wind up going national. But it’s still surreal when it happens.

G-Unit was sort of a secret handshake for a lot of local rap fans. I’m not saying no one else was aware of what was happening, I spoke to the mighty Dart Adams recently, and he regaled me with tales of meeting CD-R runners on highways between here and Boston, making mixtape drops like re-ups. I don’t really remember being able to download torrents of G-Unit Radio installments, or seeing the tapes readily available on Napster, yet I’m sure there are people who were part of online communities of file sharers who made sure these were distributed worldwide. But even beyond their scarcity, your casual rap fan in 2002 wasn’t really interested.

The tapes were out there and being circulated among people whose relationship with 50 went back to Power of the Dollar and the In Too Deep soundtrack, but the typical mixtape head from this era was a niche customer. There were some of us, possibly present company included, who wouldn’t shut up about how great they were with friends who were either more interested in Nelly on one side of the rubicon or The Roots on the other, but we were a vocal super minority up to a point this year.

This remix of what may be Missy’s most iconic single was the moment shit got real. It was Basquiat’s graffiti being mounted on a wall at MoMA. It was three months removed from 50 signing with Em and spitting on a track how badly he wanted to get on a Tim beat. And now he’s here, on a mainstream pop smash, one of the great rap pop singles of this century, with Missy, not taking a single MPH off his Queens asshole fastball.

50’s bit here is assuming a Steadman, dick on demand, rent boy character. He leans into the comedy of fucking for bread, and is giving his audience the wink and nod that he’s doing this for the money, on Missy’s own shit. Huge balls. It’s a bravura, 80s Eddie Murphy like performance, and a tipping point for 50 and G-Unit. Two months later “Wanksta” would drop off the 8 Mile soundtrack (along with God’s Plan), then he’d follow in January with “In Da club”, and the rest was history.

1. Baby Get On Your Knees (G-Unit Radio 1: Smoking Day 2, 2003)

I’ll cop to some of the entries on this list serving symbolic purposes, it’s an opportunity to go deep on certain aspects of the G-Unit oeuvre, to discuss certain members, certain approaches to their music that are worthy of recognition and consideration, but this is one from the gut, and the heart.

Busta Rhymes’ mainstream R&B bid with Mariah Carey, “I Know What You Want”, is the sort of smooth and sleepy sex pop that proliferated the airwaves in the early aughts, a time when there was a clear delineation between “soft shit” and “street shit” that 50 would soon obliterate. This song is a great diagnostic of specifically how G-Unit erased that line, taking something soft, and flipping it street, to tremendous results.

“Baby Get On Your Knees” takes something that wears its unconvincing commercial ambitions on its sleeve, with Busta Rhymes of all people reaching for a Mariah hook, and turns it into a certified romp. It’s vintage G-Unit because it pulled things out of a beat no one else would’ve thought to touch and changed your relationship with it on a fundamental level forever. It takes the barely sex scene from The Eternals and turns it into the infamous sex scene from Wild Things.

50, Banks, and Buck are all perfect. The little snippet of Banks spitting game before he jumps into his verse is a personal favorite, but it’s just supremely confident, raunchy, effortless swag. It’s 50 telling Busta, and the industry writ large, they’re literally not hitting it right. Which was always the power, and the point of G-Unit.