We do this for the culture. Please support Passion of the Weiss by subscribing to our Patreon.

Abe Beame reinforces the frails with lyrics that’s real.

I have admiration for the actual great remaining critics who can listen to new music and really HEAR it. To listen to something for the first time and accurately prognosticate shape and context, to fully digest the influence, to see the tendrils of influence reaching into the future, to understand history as they’re living it. It’s an incredible skill that a dwindling amount of publications pay not enough money for, and is of real value to culture — whatever our culture is even worth anymore at this late date.

I recall the excitement getting my issue of The Source in the mail every month. The glossy magazine cover, the weight of it. It smelled of the potpourri that was ’90s retail cologne samples. The awe I would have for these critics who got to listen to and evaluate a Lost Boyz record, still weeks or months away from release. I would add albums to my wish list based on the look of their one page. I’d buy ridiculous pairs of jeans because Nas wore them in an ad. The Source existed for try-hard, rap worshipping nerds like me.

Throughout the 90’s, The Source was rap’s paper of record. They had an incredible brain trust of brilliant writers filing long-form interviews and thoughtful reviews. Their magazine was littered with great artwork and their profiles asked all the right questions. It was delivered in a digestible 8 ⅜ x 10 ⅞ size so it would fit in your bookbag or TrapperKeeper without getting fucked up, and in my mind, crucially, it had the mic rating system.

The mics were everything that generally make most critical rating devices take off. Like Siskel and Ebert’s thumbs, or the A.V. Club’s letter grades, or Pitchfork’s decimals to the nearest tenth, The Source’s mics were an iconic, coveted prize. They understood this early and capitalized on it. It’s something that was a constant source of interest and debate. The followers of outlets with a rubric not only listen to records and watch movies and episodes of television, they watch with a secondary sight and imaginary critic on their shoulder: “Is this a B+ or an A-, a 3.5 mic or a 4?” (And even now, on the internet, many of us still rate albums on an imagined 5 mic scale).

We waited for that review to drop and couldn’t wait to debate why the critic was dead on, or out of their minds in the cafeteria. A 5 mic rating was something to be discussed in hushed tones, the Holy Grail. In 32 years, only 15 albums received it in their initial release. And The Source became the kingmakers who would decide what album was worthy of a perfect record. It demands the question, how can something be a classic when it hasn’t been released yet? How much of classic status is inherent, how much is imbued via outlets like The Source.

Before embarking on the journey of reporting this piece, I couldn’t imagine the pressure, the screaming and crying that went into determining what separates a 4.5 from a 5 (I subsequently spoke to writers Jerry L. Barrow and Riggs Morales, and Editors in Chief Jonathan Schecter and Kim Osorio). Here are some albums that missed the cut by a half mic at the moment they were released, and the magazine retroactively corrected: Enter the Wu-Tang Clan, The Chronic, Ready To Die, The Infamous, Only Built 4 Cuban Linx. And even now, as a student of history and a lover of each and every one of those albums, I can see the arguments for why they all deserved the monument, and why some, who prevailed in The Source offices, felt they pulled up just shy.

Theoretically, this is an exercise in ranking perfect albums. It decisively is not that. It’s a consideration of these albums in context. We are considering quality, but other factors play in as well. What they actually meant at the time, how able the editorial staff and the particular critics assigned with the impossible task of evaluating these masterpieces were — and sadly, but appropriately, how the institution began to trade its hard earned integrity for immediate bursts of oxygen and clout. It’s about rap, but it’s also about the evolving ecosystem of print rap media, and the art of rap criticism. Rankings are dumb and lame, but just consider it a framing method to tell the story of a magazine, an ascendant artform, and a place and time.

The critic and poet Hanif Abdurraqib called The Source, “a multi-layered beacon for culture.” And I believe, while he was referring to the magazine’s ability to take a full court approach to hip hop culture, its most powerful and lasting statement was its mics. The mics, the 5 mic honor, was not just an arbitrary ranking. It was a declaration of taste, of values, what the editorial staff wanted from these artists and this culture, the rap they wanted to make the world. And generally through 2001, their taste was impeccable. If anything they were too discerning. Too afraid of the passions of the moment, and wary of who they would induct into eternity. A judiciousness all too rare in these impassioned, hyperbolic times. A quality that, looking back, demands respect and sets an example for us all.

I apologize to anyone who is currently eating over there, but the modern-day interface for The Source looks like a place where you could catch malware if you click the wrong link. Their precious archives are largely inaccessible. For all the bullshit phallic purchases these media conglomerates make for the pub, I just really need someone to pump money into a Source.com and recover what is in danger of becoming a faded, vital document charting the modern period of rap itself.

What the five mic distinction meant to some of you was exactly nothing. By say, 1992 you were cool and there were magazines that were further underground who didn’t need a crutch like mics to share a culture that lumpen consumers like myself, of The Source and The Wiz and The Wall, were blind to. Or perhaps you’re currently young and the idea of a now obscure, niche hip-hop print magazine having such authority is arcane and antiquated and ridiculous to consider when you have the entirety of history at your fingertips. But at least for me, no medal or statue or recognition on Earth will ever amount to what it meant to get those 5 gripped XLR microphones stood up in a row on top of your review. For a time, it was as close as rap music, and the rappers that made it, came to deification.

15. The Naked Truth – Lil’ Kim

Oy. Where to start. Some of these rankings were difficult, but this one was incredibly easy. In 2005, Michael “Ice Blue” Harris writes a review that sounds like it was written by Kim’s P.R. firm (And very well may have been. There were allegations her manager at the time was dating then owner Dave Mays). This was a time when The Source was struggling, with ownership and editorial staff in flux, and they clearly were reaching for a headline by giving this album 5 mics. I’m just an idiot who dicks around on his laptop, but the one real All The President’s Men worthy act of heroic journalism I’ve done in my life was skimming through this album to do it justice in this blurb, and let me tell you, it’s bad folks! It’s a really petty, stupidly rapped, rudderless and overlong album with consistently terrible features. 3 mics would be incredibly generous.

At one point, I guess, to prove he gave the album a cursory listen, Harris writes, “the girl is on fire with heat like ‘I’m comin atcha like two planes in midtown’.” This is terrible criticism on so many levels. The song itself, “All good”, sucks. It’s a string of lazy and probably ghostwritten references clumsily spit over a Biggie vocal sample, trendy at the time and probably the worst example of one I’ve ever heard. The quoted bar itself is Kim saying she would do a 9-11 on haters, already in bad taste, but the Twin Towers were in the financial district, a person with a loose understanding of the city’s layout, let alone a born and raised Bed Stuy product, should know that, but so should any critic! For all the stupid bars you could reference in your review, THAT’s the one?!

To gild the lily, he fucks up the quote! Kim doesn’t say, “I’m comin atcha like two planes in midtown.” She says, “I come through like two airplanes in midtown.” So it’s not just a failure of criticism, but an institutional failure that trickles down to editorial and fact checking. This may be persnickety, but again, I’ll remind you, this is one of 15 5-mic ratings that have ever been awarded in the HISTORY of hip hop. At this point I will tread incredibly lightly but just say my personal, unreported impression is that connections began to hold sway over the rating system. It became (for a time between Osorio’s stints at the magazine) journalistic payola.

This shows the publication was floundering, with writers who didn’t have a clear sense for where the pulse of the culture was. They badly reached for an album they could elevate to spark controversial headlines, and settled on a weak late contribution from a New York rapper making shit New York rap well past its prime. What makes it worse is, in the very same Record Report, in fact, the very next review, they had a legitimate 5 mic album contender. It was Young Jeezy’s Thug Motivation 101. They gave it 4 stars.

This was my personal funeral for the once August publication of my generation.

14. Trill OG – Bun B

Once again, this smacked of a publicity stunt. Five years after the Kim debacle, Bun B, an all time great rapper who spent most of his career in regional obscurity, spent the first decade of this century getting his overdue recognition, but it was far from a victory lap. Almost immediately following UGK’s crossover,“Big Pimpin”, Pimp C spent 5 years in jail. When he got out, the group released a single, wildly successful album, followed by Pimp C’s tragic death four months after the album dropped in 2007.

So for these reasons, it’s understandable why The Source, or anyone really, would want to see Bun win: It’s a hell of a narrative. And this will start to emerge as a trend, evaluating the artist’s career and narrative alongside, and occasionally above, the actual album being considered. But his third solo is a far from perfect album. It’s laden with meh features and random production credits, including a hip-hop head bait Premier sighting, and as most of the critical landscape was quick to assess, it’s a perfunctory, boring album. Still, perhaps by default, better than The Naked Truth.

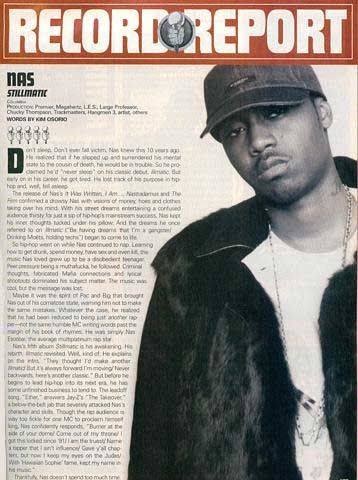

13. Stillmatic – Nas

In my intro I spoke to the difficulty of really seeing a moment, being able to see through the noise and smoke and properly contextualize an album, separating quality from hype. 5 mics for Stillmatic was one of those moments where The Source was unable to do that. Or was it?

The battle between Nas and Jay was raging in 2001, and this was Nas’ side of the salvo. It was largely a dumb beef that was a product of heightened egos and a little desperation on Nas’ part, but the drama between the two New York legends was very real, and great for ratings and magazine sales (In September 2002, a cover featuring Jay-Z was the magazine’s all-time best selling issue).

But let’s take The Source at their word. It once again makes a great deal of narrative sense. This is Nas, their golden child, coming off Nastradamus, which caused even many of his devout followers to leave him for dead. It was an early 5 mic review that anointed Nas, and solidified the magazine as a vital tastemaker. Kim Osorio, en route to becoming the magazine’s editor in chief, wrote the review. She positions the album as a return to form, that he had meandered through the mid to late 90s dabbling in Scorsese rap, but finally returned to his roots and has delivered the successor to Illmatic we’ve waited a decade for. That he was able to do this while dethroning his fellow New York City rival, made it more than an album, it was a cultural event. And on this point, I agree.

When I spoke to Ms. Osorio, she helped me understand a specific quality that came to dominate The Source in their consideration of what was deemed worthy of 5 mics: The resume of the individual. Certain rappers were worthy of deification, and certain rappers, regardless of the bells and whistles of a major label budget, blue chip production, and street hype, simply would have to do more to prove themselves worthy of the rating. In theory, this serves as a logical and a natural vetting process: Only the best deserve enshrinement and entry to an exclusive club.

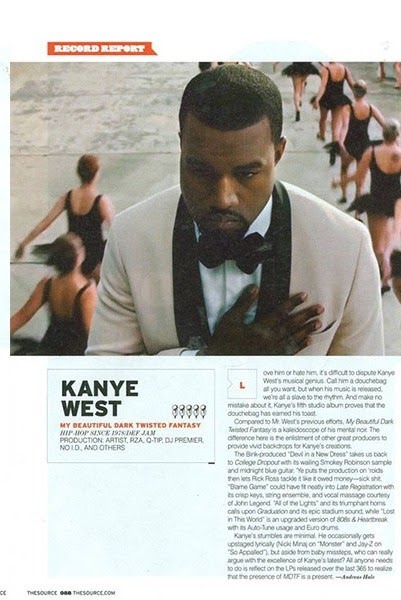

But it also is a slow erasure of objectivity, and a story of how institutions calcify. In the beginning, The Source regularly awarded 5-mic ratings to debuting talent: Ice Cube, Nas, A Tribe Called Quest, and Brand Nubian. The longer the magazine existed, the deeper in artist’s careers the 5 mic album came: The Fix is Scarface’s seventh album, The Blueprint is Jay-Z’s fifth, The Naked Truth is Lil Kim’s fourth, My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy is Kanye’s fifth. At one point with Ms. Osorio, we discussed her regrets. They include Kanye’s debut, as well as Kendrick Lamar’s, both of whom were passed over with her as EIC.

She said, of Good Kid, m.A.A.d City, “To think what (Kendrick) did at that time in hip-hop, and where the culture was, and who he is now, that would’ve been a great decision back then.” What you can see is regret that speaks to future performance, what it would’ve meant to The Source to recognize a rapper who would go on to become one of the greatest rappers of all time, rather than to have properly evaluated a great album on its own merits in the moment. It is the product of an understandable and unenviable position.

With an institution like The Source, after a period of time you aren’t just battling your own critical function, but the weight of history. There is almost a kind of fear in giving 5 mics to a young ambitious rapper with a squeaky voice from Compton, you don’t want to be the person who was in charge when historians discover some random West Coast rapper no one ever heard from again got a perfect rating, it devalues the entire enterprise. Before long, you may find yourself saying, “Sure this is good, but is it as good as Illmatic?” An impossible standard. And this is how you move from doing the work of unearthing and elevating new and exciting talent, to safely coronating known entities and telling everyone what they already know to be true.

To be fair, Stillmatic may actually be a tad underrated in 2020. If it simply ended with track 10 (as Illmatic did), it might have even been worthy of its rating. It’s full of the brilliant and wildly original concept songs Nas would litter his projects with going forward; he’s reinvigorated on the mic, the songs are mostly catchy and the production is good…….. for the most part.

But it’s a 15 track album. 5-mics is not an award for good albums, or even great albums, it’s for perfect albums. Classic albums. Albums that change the world. You can’t have “Braveheart Party” on a perfect album.

12. Let the Rhythm Hit ‘Em – Eric B. & Rakim

Three 5 mic albums were released within three months in 1990. There are a number of angles to consider this from. The first is, it was an unprecedented glut of classic music. Let the Rhythm Hit ‘Em, AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted and People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm. One for All was only a few months behind. They are all important, iconic records.

But this means over a quarter of all the 5 mic albums ever made came out in a year. And, as you can see above, some of these reviews look like the descriptions of an episode of a show you’d read in an old TV Guide. My theory is, at least initially, The Source, launched as a trade paper, did not recognize what a precious commodity a 5-mic rating was. It was given to classics, but also very very great albums, like this one from Rakim, winding down his peak run from the mid to late 80s. A young Large Pro stepped in for the legend Paul C after he was gunned down at the age of 24. The album is possibly the most cohesive Rakim and Eric B. project, littered with filthy bass lines and horn riffs. But when evaluating it alongside a murder’s row of other perfect albums, it’s one in an immaculate catalogue, an easy call. Perhaps too easy.

The editorial staff seemed to tighten up and get much stingier with their mics soon after.

11. My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy – Kanye West

The Source finally gave Kanye the accolades he’d been demanding for nearly a decade. Every outlet on Earth was practically required to award this a perfect ranking. Assuming the magazine is never rescued, this will go down as the last 5 mic album in its history, which is appropriate because it was the last moment of universal pop consensus we’ll ever have. I believe The Source made the right call. This album has aged incredibly well, foreshadowed much in Kanye’s life as well as this county’s, and it still fucking slaps front to back. But this was also basically a bunny in its moment. It would’ve been inconceivable to award it anything short of 5 mics.

10. One for All – Brand Nubian

Our first sighting from a Native Tongues peripheral affiliate, which, *spoiler*, will be a major talking point throughout the rest of this piece. Brand Nubian’s debut was a phenomenal album. It took many of the loose threads left by the Last Poets, the Jungle Brothers, KRS-One, Rakim, Public Enemy, and many of the future cartoonish excesses (of B-boyism and 5 percentism) that would eventually be championed by Wu-Tang, Jeru The Damaja, or, uh, KRS-One, and threaded the needle. They are the rap equivalent of the Black Panthers Free Lunch Program, a marriage of high minded political philosophy and grounded civic duty that produces real, tangible results.

The trio produced an album that flexed brain and bottom, freeing political diatribe from the throbbing production of the Mind Squad and grounding it in the everyday, making it danceable and cool. The production team of Brand Nubian themselves, Dante Ross and Dave Hall set the stage sonically for Q-Tip and Tribe. And The Source was quick to jump on it, declaring itself as a publication that highly valued Brand Nubian and The Native Tongues brand of scholarly, racially informed, politically aware lyricism that maintained its funk at all times.

Its position on this list is due to the fact that the album simply hasn’t aged well. The rapping, and most of the politics hold up, but the simplistic James Brown loops, with its monotone discursive verses and non existent hooks, kind of run together. It’s littered with iconic moments, but it’s overlong and doesn’t have the same out of time quality that many of these other albums capture. It serves more as a vibe than an album, and it’s a great vibe, but the albums below are better.

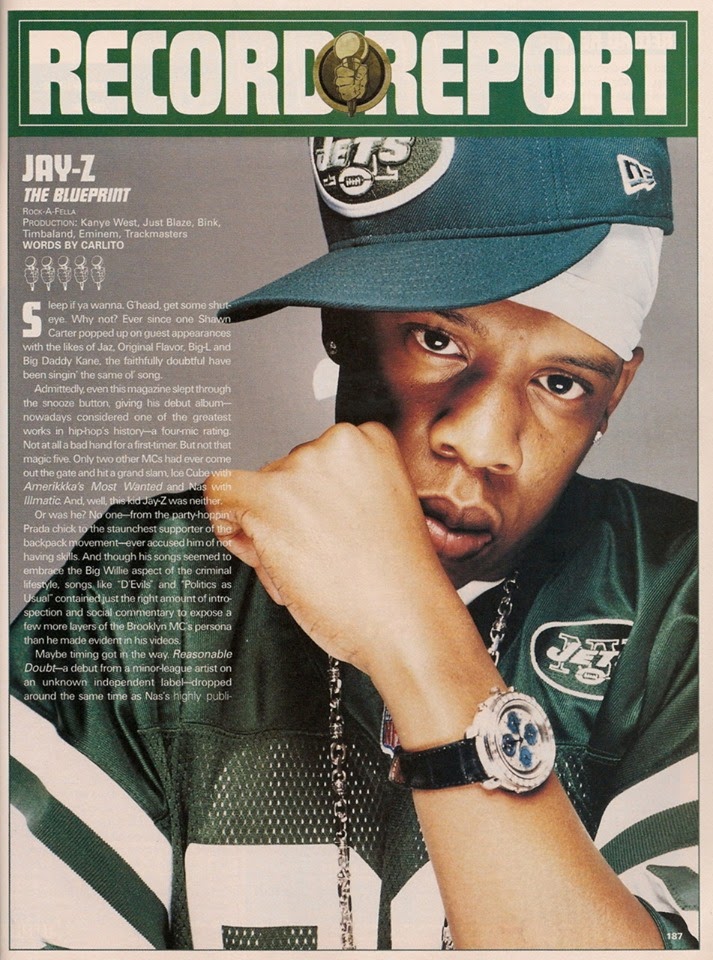

9. The Blueprint – Jay-Z

I’m going to tread very lightly here, because this website called this album the very best of the aughts (Author’s note: Insert Ed. Note Here — Ed. Notes — Look we all knew it was “Supreme Clientele,” but as we know now, democracy can lead us astray). In many ways, The Blueprint is The Source’s greatest triumph. It is the direct codification of an understanding of what the Ivory Tower critic class wanted from its New York album rap in the 90s, made by its absolute best marketer and saviest son.

Marcy’s own Shawn Carter understood the formula to generate a 5 mic album was a tight tracklist, composed of a murderer’s row of culturally relevant producers, with carefully considered features and a heady blend of personal and commercial tracks. Consider Jay-Z’s album that preceded The Blueprint, The Dynasty: Roc La Familia. It’s a sprawling, 16 track album that some consider more of a compilation than a Jay-Z solo. But many of the elements that will elevate The Blueprint to classic status are present on Roc La Familia. Blueprint is, quite simply, an intentional act of myth making. It’s Roc La Familia edited by Gordon Lish, or the Mind Squad.

This takes nothing away from Jay’s incredible, generational talent. Perhaps with the exception of LeBron James, I can’t think of another individual who can digest history and shit it out as an act of will. You or I could understand what it would take to make a classic rap album, or put together an on court season historians will debate for a century, but we lack the intelligence, grace, and skill to execute it. Jay did, and it’s not a chore, it’s a great fucking album.

But still, what’s incredible to me about The Blueprint is it’s a clear example of a snake eating its tail, and that snake is The Source and the standard of rockist, East Coast oriented greatness it quite literally created and saw manifested by Jay with The Blueprint.

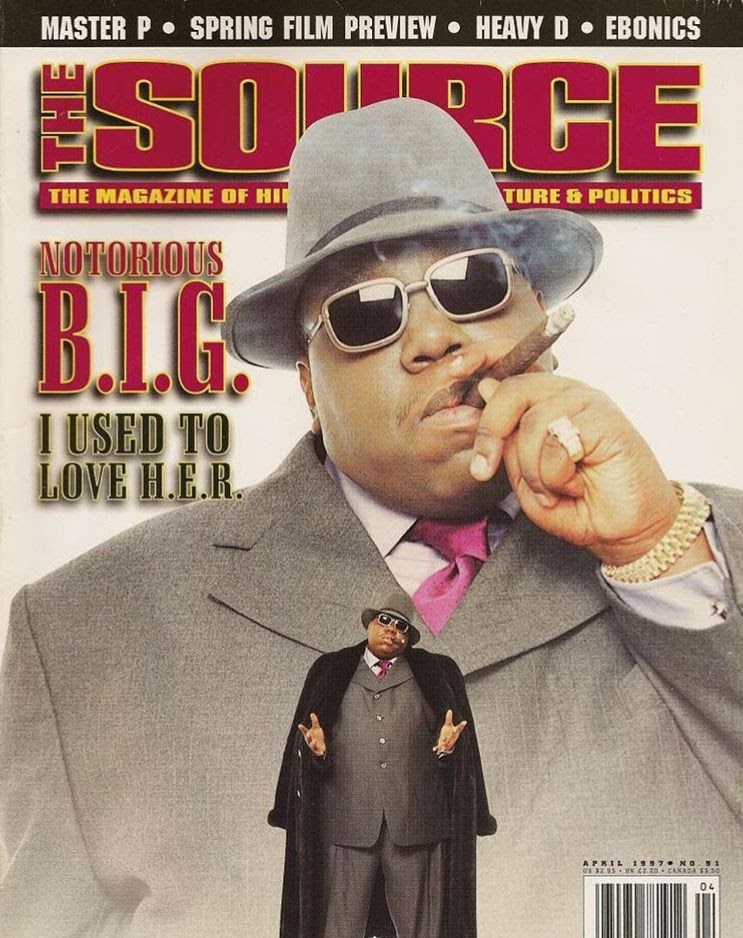

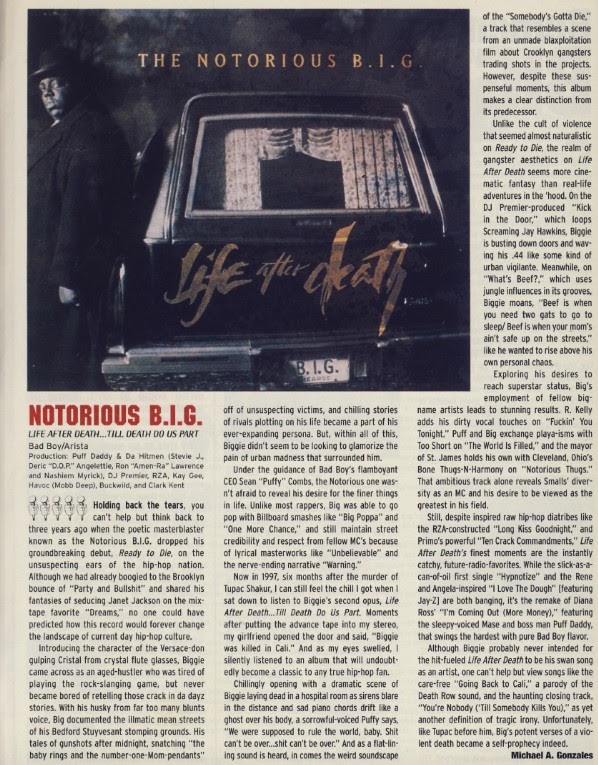

8. Life After Death – The Notorious B.I.G.

A tough one. The hardest decision on this list by a wide margin, but it must be said. When you start your review of an album with the words, “Holding back tears”, you’ve already given up the game.

There’s a valid debate to be had here over the role of the critic and the limits of critical function. Is the role of a critic to call balls and strikes? Is there such a thing in music? I think so, to an extent. I rarely evaluate new music (and I’m not a critic), but when I do, I’m considering what the artist is aspiring to and how “successful” they are in that endeavor. And again, we are getting deep in the muck for a frivolous listicle, because what does it mean to be successful? It just means you, with your biases, prejudices and shitty taste, like the music, but I think Life After Death is an exemplar of why the MOMENT can be so dangerous when evaluating art.

I can’t really express how much sympathy I have for Michael A. Gonzales. People were openly weeping in the streets when Biggie died. It was fucking shocking. I was 12 years old, and I sobbed. For people who didn’t even like rap, this was a cultural touchstone. But the question when considering Life After Death in this context is how much did Biggie’s death influence the actual album’s rating?

It’s Biggie rapping, so of course it’s great, and this is the most cliched and obvious criticism to direct at a double album but sorry, it suffers from sprawl. And it’s not really unfair because Big leans into the sprawl. There’s a Midwest record, an L.A. record, a Bay record, several street records, a Casino riff with Lil Kim, some dazzling lyrical showcases, a Bond theme, a few Diddy inflected pop records, dumb skits, several story tellers. It’s quite intentionally experimental and all over the place. It’s an artist with limitless gifts stretching his legs and beginning to consider where he would take his art next, and the vastness of his options makes for a daunting sit. It’s an album where you can single out any one song and it’s probably fantastic (there is a skip or two for me depending on mood, but like anything Biggie ever made, any one song of his could be one person’s favorite and the next persons least favorite) but sitting through the entire thing and considering it as a whole isn’t really what it even feels intended for.

I realize this is chiseling Mount Rushmore with a scalpel, but we are approaching seven of the greatest albums ever made (and The Source’s evaluation of these albums in the moment. I’m NOT saying Life After Death is less than any of the subsequent albums and their reviews), so my job at this point is to evaluate and order perfection, and in my estimation, this was the greatest rapper who ever lived in transition. And the writer, very understandably, got carried away in the moment. Is any of this really fun to talk about, criticizing my favorite rapper of all time, or interesting for anyone to think about besides me? Probably not. But I had to say it.

7. AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted – Ice Cube

This album has a lot of narrative advantages that help explain why it was an ideal candidate for 5 mics, coming on the heels of O’Shea Jackson’s departure from NWA. Cube set off rap’s player empowerment era when he passed on the shit deal that he had received from Eazy and Jerry Heller. There was some question whether or not Cube would be able to break out without his group, or Dre’s production (Cube and Dre wanted to collaborate when he went solo, but Heller blocked it), which Cube resolved by track 2 of this instant classic.

In addition, this was the perfect Trojan Horse for The Source to diversify its HOF because in lieu of Dre, Cube looked East, to the Shocklee brothers, Vietnam, G-Wiz, and Bill Stephney, also known as Public Enemy’s production team,The Bomb Squad. Their righteous noise collages were perfectly matched to Cube’s prophetic anger, burning L.A. in his songs a year before the city would raze itself. The album was even recorded in New York.

So theoretically, this marriage of East and West made Cube somewhat more accessible to the Mind Squad, and got him his 5 mics, a distinction Snoop and Dre never earned. It would take nearly a decade for any other artist outside of New York to land a perfect score.

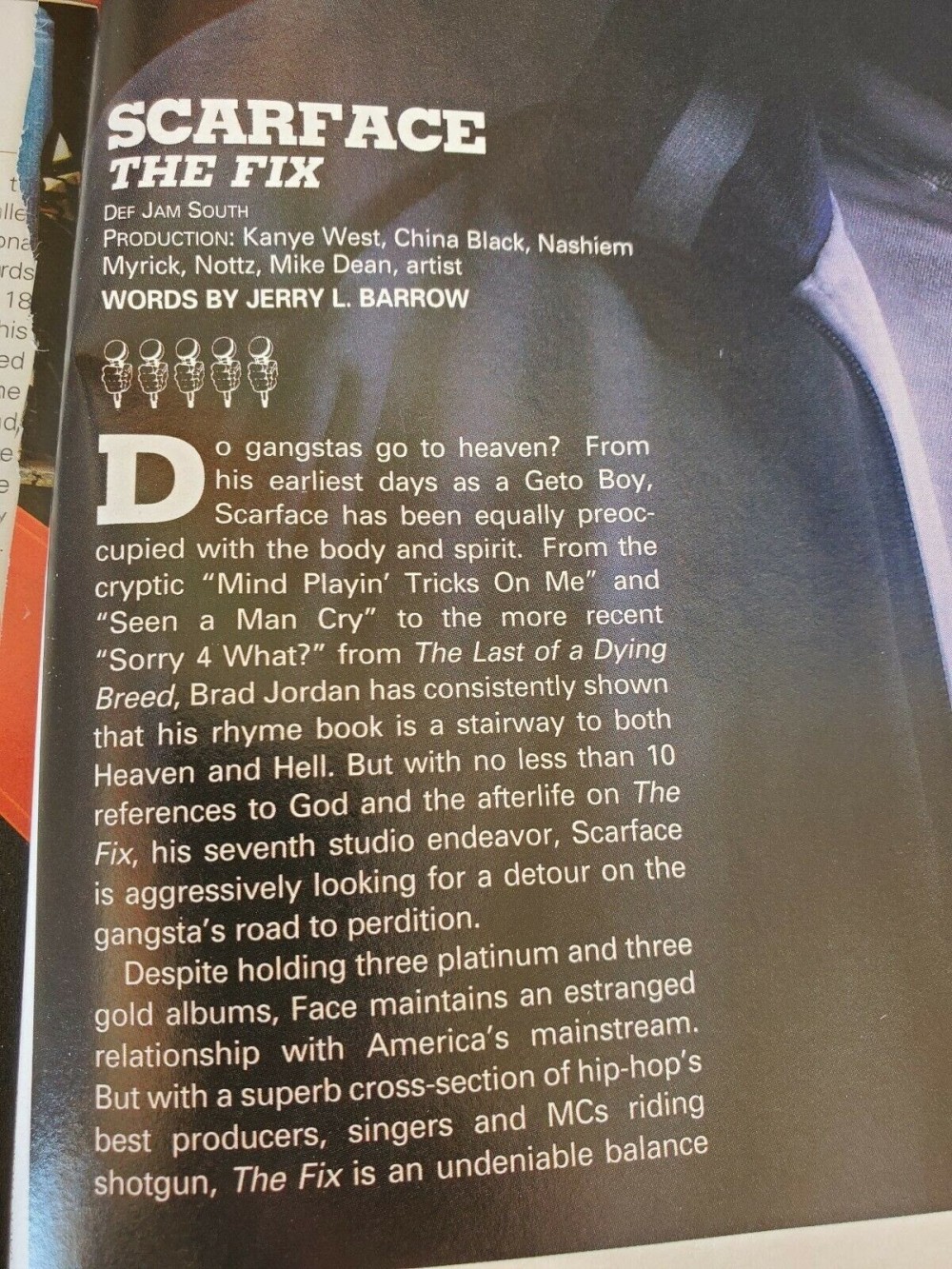

6. The Fix – Scarface

This review is very much 1 and 1A with The Blueprint. It’s an album that remains “Perfect,” but Perfect in this very codified New York sense of what makes a classic album. Scarface’s history, like Jay’s, was messier, dirtier, and some would argue, more interesting than the impressionistic masterpiece that is The Fix, but think of this like a lifetime achievement award.

Writer Jerry L. Barrow’s review brings out an interesting element of the album, a quality Scarface could only have achieved with age and time. The Fix is at times a morose and remorseful album, a quality that would dominate the aughts for Face, in what was a great decade that rivaled his incredible run in the 90s (Almost 10 FUCKING YEARS AGO, I wrote to this quality myself, in what I’m pretty sure was my first piece ever for this site). It’s a credit to the critic for recognizing this quality, and in my mind, gives Face an edge over Jay-Z, because while Jay-Z more or less refined his schtick for his 5-mic bid, Face introduces something, if not new, more pronounced in his music, a pretty incredible accomplishment 18 years into his already legendary career.

When I spoke to Barrow, he reminded me that the album was also an event, a kind of coronation of Brad Jordan’s career. It was his first release with Def Jam after becoming the president of their monumental, map shifting imprint, Def Jam South. He had won Lyricist of the Year at The Source Awards in 2001 for Last of a Dying Breed. With nearly 20 years of work put into the game, Face called in every chit here. He united Nas and Jay-Z on his album at the height of their beef. His tight, 13 track album featured production from Mike Dean, Kanye West, T-Mix and the Neptunes. It had all the earmarks of an Important Record.

We previously discussed the idea of the rapper’s personal narrative factoring into how he or she was considered when evaluating an album. Something Barrow told me is in many ways, Scarface is the embodiment of this concept. He traded on a career of greatness and was awarded with a legendary distinction.

That being said, this was before the Atlanta revolution in the form of Jeezy and T.I., before rap relocated its powerbase to the South. Scarface had been this iconic figure, but we still hadn’t fully brought the national continuum of rap into the fold as one flowing and unified thing. 50 was about to drop, the Diplomats were emerging, I would guess at the time, based on personal experience, The Mind Squad juggled this album with any number of Clue, Kay Slay and Whoo Kid tapes. And yet.

Face is impressive for delivering a Classic, Perfect album. The Source is admirable for giving a work of pure craft its due, particularly because it came from out of town. And yet it has the apple polishing blueprint of The Blueprint on it, and it doesn’t really stand up to the foresite the publication showed when it awarded 5 mics to another, perhaps, “less formulaic” and “more organic” Southern rap album several years earlier.

5. The Low End Theory – A Tribe Called Quest

The two 5-mic Tribe albums are five and four on this list, and I wrestled with which order to rank them in. The case for Low End Theory is strong. It’s not the same jarring shift we saw with Tribe’s Native Tongue peers on De La Soul is Dead (though it does contain some of that albums music industry vitriol), but that speaks more to just how polished a sure footed their debut was. Low End Theory did all the things a sophomore album is supposed to do. It raises the stakes, shows maturation and polish, less irreverent without being overly serious, and most importantly, establishes the chemistry between Phife and Tip that made the group what it became, rather than one genius calling himself a group.

Nominating People’s Instinctive Travels took guts and vision. But Low End took a different type of courage. No group before Tribe, and no group after Tribe, prior to Stillmatic, would receive a second 5-mic rating. Tribe did it on their first two albums. The Mind Squad had to know they’d be accused of playing favorites, of devaluing other valid contributions, and in many ways they did. Of course Dre and Snoop and Big and Pac and Outkast and any number of legends making classic albums during this period deserved the accolades Tribe received, but we can say that comfortably with hindsite. They had the confidence to say, this is the hip hop we fuck with, these are our guys, if you don’t like it, Vibe is directly next to us on the magazine rack.

Low End is a more complete album. It’s at once of a piece with People’s, and sets the stage for Midnight Marauders (A rather mystifying 5-mic snub in my opinion, and others who actually feel Marauders is Tribe’s best effort). But ultimately, in my estimation, The Source’s prophetic decision to anoint a less perfect debut from an important talent was the greater work of criticism.

4. People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm – A Tribe Called Quest

The most appropriate album opening in the history of hip hop may belong to People’s Instinctive Travels and The Paths of Rhythm. The equally appropriately titled “Push It Along” begins with a mystical shimmering, a birth of consciousness, followed by an infant’s cry, its physical manifestation. What follows is 65 of the most important minutes in the history of rap.

Many smarter and better informed critics have discussed and written entire books on Q-Tip, Phife Dawg, Ali Shaheed Muhammad and Jairobi’s accomplishment, so let’s try to consider the album through The Source’s lens.

What Matty C’s review, solidifying the group and album in the eternal pantheon, immediately identifies is the not just the introduction of a group, but of an aesthetic, a fully formed mission statement that Tribe put out into the world, whose smooth and funky rhythms contrasted wildly with much of the muddy noise that populated rap in the early 90s. This is taking nothing away from that brilliant, explosive muddy noise, but Tip’s devotion to his seemingly endless supply of supple riffs was a moment of maturation for hip hop itself. His New York, related in a way that was at once cosmic and common, changed the way we would think about and rap about the city. The Source recognized this.

I asked Jonathan Schecter if there was an implicit bias in how the staff at the time evaluated records. If their critical coupling with the Native Tongues collective (who own 5 of the 15 5-mic reviews) was a conscious declaration of principles, or a coincidence. Schecter said they made an effort to maintain objectivity and truly believed they had done so, evaluating each album on its specific merits that would lead to bloodshed in their offices, as the mic ratings were done by committee throughout the history of the magazine. They knew from the beginning the mics were their calling card, and agreeing on an appropriate grade for certain controversial albums caused all out wars.

Still, the albums they ended up settling on made a kind of sense. The core editorial staff in New York was almost exclusively Northeast products. All bright, all well versed in the history of rap and all naturally more exposed to the history of rap in its birthplace. A project like Native Tongues, which began to come together around the same time as the magazine itself, was made for the staff. Tribe and De La in particular are full of the winks and nods, the references and in-jokes, a crew of young, smart rap nerds would fall hard for. As a producer, Q-Tip’s reverence for his musical ancestors was both backward looking and progressive. It’s a quality that speaks to an academic approach when it comes to making music, as well as considering it.

Listening to Prince Paul relate his experiences with Native Tongues on his essential retrospective podcast, What Had Happened Was (something I have to assume you’ve listened to in full already if you’re dedicated enough to read this shit, and if you haven’t, fuck is good with you?), what comes through is a magical, free flowing historical moment when an eclectic collection of characters were in the right place, at the right time in the studio together. They were collaborating in a loose and free flowing way, sharing lyrics, records, ideas, techniques and styles to build something that literally changed the culture. It kind of sounds like what it must have been like at The Source in those halcyon days.

3. De La Soul Is Dead – De La Soul

It’s become something of a cliche, but De La Soul’s second record remains one of the hardest left turns in the history of rap. The album was a conscious refutation of the bohemian hippie packaging Tommy Boy shackled to the group on its 1989 debut, 3 Feet High and Rising. The Amityville trio and producer Prince Paul, kicked in the door with a firmly entrenched iconoclastic streak. Their approach to album rap, in terms of its intricate layered sampling and irreverent, full-album-experience world building, changed the way rap would sound for the next 20-plus years. With their follow up, they replicated certain aspects of that approach while literally killing what the band represented in the album title.

The success of De La’s debut was stunning to everyone, including their own label and the group themselves. The pressure to one up what they had produced was intense, so they pushed back. It was a killing of the idea, the persona the group was misrepresented as, visually conveyed with the destruction of a D.A.I.S.Y. on the cover.

De La Soul is Dead is a meaner, colder album, an airing of grievances. It’s a catty, petty work of self correction, self-expression, self-realization. Even sonically sunny tracks like “Bitties in the bk lounge” are sneering. Struggling with their fame, reveling in it even as they push it away with great force. They are railing against the emptiness of music industry fame, the transactional nature of love and lust that comes with success, and it’s all related in their rhythmic, broken, dense beat poetry that demands untangling on multiple listens. As Prince Paul himself eloquently refers to it: “Styles and rhythms that you’ve never heard before.” Their eclectic, scholarly, hyper referential nerdism.

It’s a writerly album, an album that thumbs its nose at the concept of a serious and high minded album even as it is defining that very quality. It contains mature, dark storytelling, disguising its social messages in ways that push past the lazy hard luck narratives that preempted it. It elevated the form to a modernist level. It was formally daring and experimental, constantly playing with character driven voice work and shifting POV, mirrored by beat switches and scratched in ad libs. It was an incredibly sophisticated nihilistic joke delivery system that explains why Paul was such a natural fit for Chris Rock as his Rabbi several years later. The production and flows remained effervescent, for the most part, and this obscured the sharp, unpredictable detail and surprising but sadly believable conclusions that made their songs resonate in a way rap hadn’t before. But it required work in a way much of the music that came before it hadn’t. It was knotty and difficult and made for headphones rather than stereos.

It’s a frustrated, aching work of art that doesn’t sound like one without proper reflection. They gave us all the album we didn’t want, but we needed, and they had to make. De La made convoluted pastiches, ransom notes composed of letters cut out of an infinite sampling of every form of media on display at a LIRR magazine stand and super glued onto a single album. That The Source, so early in its life, was able to parse through the noise and recognize the perfect imperfections of this project, to immediately grasp the intentionality of the effort and appreciate its overstuffed brilliance, is remarkable. Decades later, I can’t help but feel that the original triptych of De La and Prince Paul collabs represents the closest this era of primordial New York hip hop came to disruptive, chaotic, rule breaking art. The De La/Prince Paul brain trust was Marcel Duchamp, and De La Soul is Dead was their urinal.

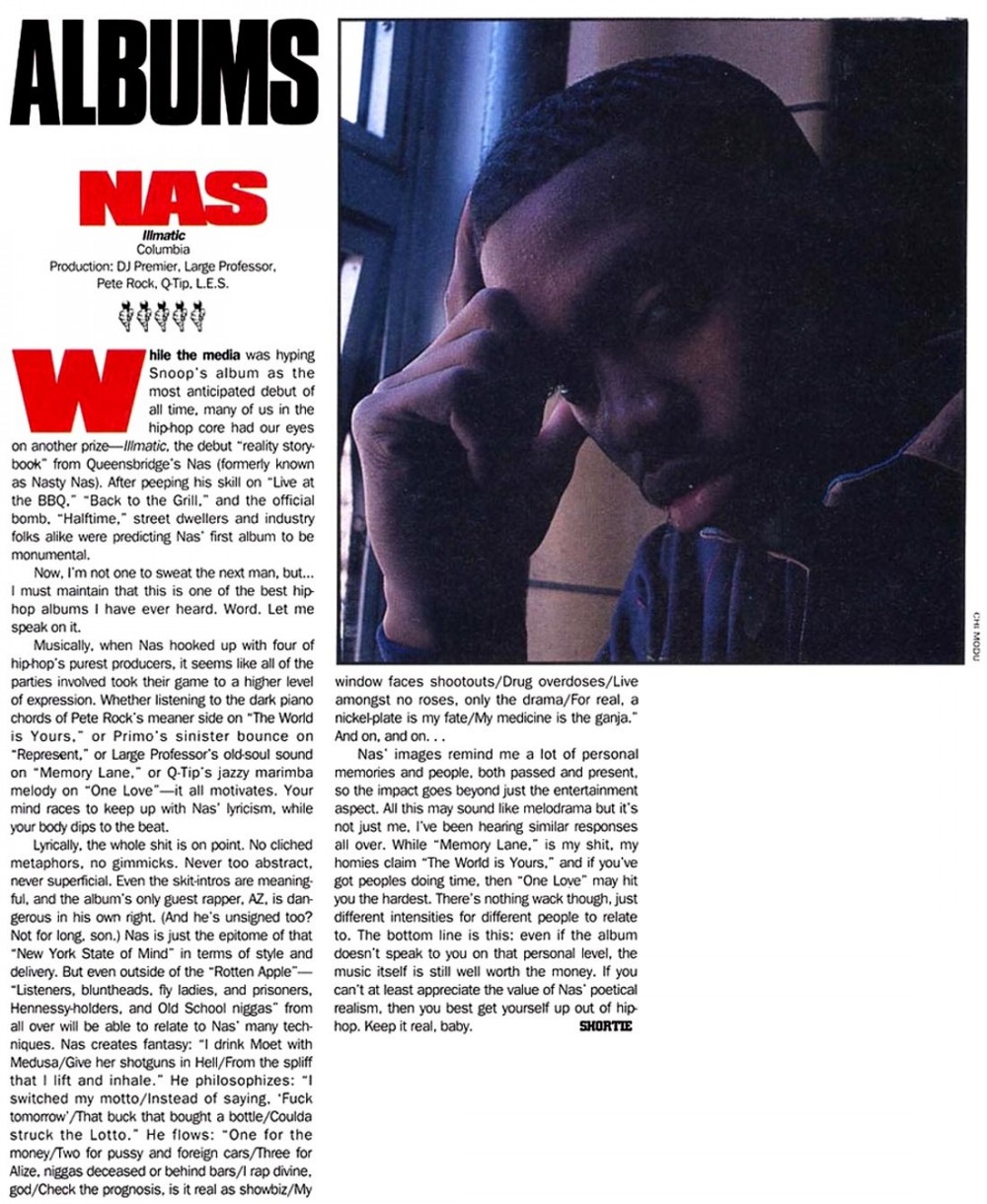

2. Illmatic – Nas

If this piece was a pure, context-free consideration of evaluating greatness, Illmatic would unquestionably be number one on this list. The ranking is a triumph of not just criticism, but journalism on the most basic level. I spoke with Source Editor In Chief at the time, Jonathan Shecter, and he shared a rather incredible story of how he first came upon Illmatic.

Schecter, a Philly native, went for a sit down in the Philadelphia suburbs with Chris Schwartz, the former manager of Schooly D and then president of RuffHouse Records. Schecter was there to talk about the projects the label had on the docket, bigger acts at the time, such as Cypress Hill and the Fugees, but really there to subtly push some ad buys, and just in passing ended up in the possession of a rough cut tape of Illmatic, eight full months before it would hit the market.

At the time, Nas was a shamanic figure. A teenager who had appeared on a Main Source posse cut (a single The Source had also awarded five stars when it awarded single releases mics), a retread in the form of “Back to the Grill Again,” and an album preview of “Halftime” off the soundtrack for a Michael Rapaport vehicle. He was a hotly anticipated artist, but there was no telling where a guy who jumped on a Large Pro track and bragged about snuffing the son of God was going to take his music. Was it a single inspired verse, or the introduction of an artist who would change rap? Would he be a staple in our lives and our discourse from that moment till this one?

And this is the literal point of this piece. Imagine being Jonathan Schecter with a Walkman, on the Amtrak back to New York, listening to Illmatic, perhaps as the very first person on Earth hearing this thing blind, with no idea what you’re about to hear, for the first time. Is recognizing greatness and brilliance a gift, or is it immediately apparent with the appropriate amount of context?

The album was brought back to The Source offices and played for the Mind Squad. And this is my favorite part of the story. The review was assigned to Minya Oh, a young intern who got the assignment because the editorial staff trusted her intelligence and acumen. And she proved them right by writing, what is in my opinion, the best review on this entire list. She hits all the right notes, the full body and yet out of body experience I am reminded of when I think about hearing this album for the first time. She captures its personal and universal qualities, the way it represents something incredibly intimate for each of us even as it retains a timeless quality for all who came before and will come after.

As Miss Info says herself, the ancestors speak through this album. By the point in my life I really heard Illmatic for the first time, it wasn’t just an album, it was the weight of history, the pressure of appreciating a true masterpiece, the understanding that now, finally, I was listening to ILLMATIC, a gravity and a sensation she personally helped create. The architecture of her review, its understanding of the moment and its echoes in history, are exact.

In many ways Illmatic serves as a bridge between the 80s and 90s. Along with Wu-Tang, it’s the first steps of an emergent postmodern consciousness, a shaking of hands between Bronx kids like KRS and Big Pun, a synthesis of style and content that paved a road forward. Kids don’t really rap like Q-Tip anymore, but some still rap like Nas. With a brain trust of 5 mic producers and artists who had made the monolithic New York of the early 90s, Nas became the avatar of where New York rap went, for better and worse, through the rest of the decade. That legacy was solidified with his debut album, and the conversation around that album The Source was largely responsible for.

There are these moments, moments of awakenings. When art forms, entire mediums, suddenly find their bearings, realize everything that has come before has only scratched the surface of the possible, and a select few are privy to this knowledge, these possibilities, before the rest of us. In these moments, those select few hold the universe in the palm of their hands. I’m thinking of Paris in the 20s, Motown in the 60s, Paramount in the early 70s, and the Native Tongues, here in New York, at the end of the 20th century.

These moments, in retrospect, and even I’d imagine, when you’re in them, feel like detonations, like permanent shifts in culture, even life. But our art isn’t like that. We are not like that. The moment you produce a Sun Also Rises, or a What’s Going On?, or a Chinatown, or an Illmatic, the culture shifts, you become a sound, a replicable equation. The culture demands form, a place to go to that it can interpret and categorize and emulate. And before you know it, you’re in Vegas, in a Sam Rothstein Halloween costume, rapping over a straightforward Trackmasters Eurythmics flip, trying to find the magic you didn’t realize you had left behind.

But it would be a fucking crime, a crying shame, if we didn’t recognize the prescience of the Mind Squad, and Minya Oh, and of course, Nas himself, if we denigrated this crucial moment in our history in any way because of what came later.

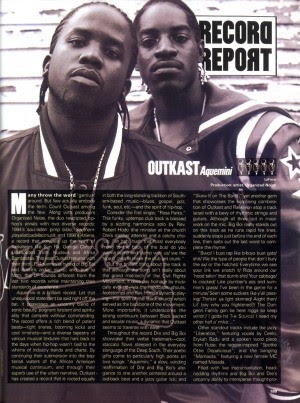

1. Aquemini – Outkast

While it seems obvious now, in many ways, anointing Aquemini was a courageous act. A paradigm shift. Also, ironically, by giving Outkast the flowers they so rightfully deserved, The Source at once legitimized their rating system, and acknowledged their death knell. In many ways, this signaled the end of their position at the summit of hip hop.

Writer Riggs Morales was at the magazine at the time. In his years writing there, this was the only 5-mic album he was at the magazine for. It was editor Selwyn Seyfu who introduced the album to the staff with the suggestion it was worthy. The staff was stunned, but Seyfu had spent more time with the album than they had. After giving it a few spins, everyone was in agreement.

It fits what became the rubric for a 5-mic album: It’s a third album that articulates all the things the group had been working toward. They are fully matured, understand their dynamic, understand their sound, and deliver the most perfect version of that on every level. ATLiens is still my favorite Outkast album, but I can acknowledge Aquemini is “The Best”. The group had amassed popular success with a few radio friendly singles that maintained integrity, as well as critical love, and this album garnered plenty of both. It’s full of hits without sacrificing an ounce of its brilliance.

But it’s not just a matter of resume building. Who Outkast was mattered. They were literary, intelligent and grounded in a way that makes sense to All The Critics in New York. Their spacey urbanity gave a Southern twang to a language Nas and the Native Tongues had consecrated earlier in the decade. In retrospect, while it came later than it should’ve, Outkast was the perfect vessel to break The Source’s Mason Dixon line.

The story of The Source mirrors the rise and fall of the modern era of New York Rap. Much like groups either in or affiliated with the Native Tongues collective, The Source was an intelligent, preternaturally mature outlet with a grasp on the history, the scope, the knowledge of self, and the importance of hip hop, before much of the music crit industrial complex could differentiate the forest from the trees. Like the early genre itself, the magazine gained wealth and clout as the industry exploded and rap went from a regional niche genre to the mainstream. With that money came compromises, scandals, power struggles and a slow decline in the quality, and clarity in the thinking and reporting coming from the Mind Squad. As hip hop moved its base away from its birthplace and New York lost its venerated status, The Source lost its way. It’s a neat and reductive metaphor, but it’s also true.

It may be over, but we can at least look back with wonder at a time when New York stood for rap music, and one magazine stood for New York, speaking in a clear and authoritative voice we may not have always agreed with, but we all heard.