Image via Pendarvis Harshaw

Dr. Dre’s The Chronic being listed as one of the best Bay Area rap albums is why Alan Chazaro doesn’t trust anything generated by AI.

When I met up with Keak Da Sneak in San Francisco, he wasn’t the same Keak I’d grown up seeing in MTV music videos and hearing blap from Sony speakers at house parties. This Keak was bound to a wheelchair after having been shot at a gas station in Oakland, and though generous in spirit, he seemed more grizzled and wise. His raspy, weighted voice reminded me of the Bay Area’s wildest yesteryears, when he and so many other artists from this region brought a tsunami of energy to the hyphy movement.

As we spoke in front of his all-black truck while he smoked, his right hand man posted up by his side, I asked him about how he felt that we — rappers, OGs, journalists and fans of Bay Area hip hop — had all gathered that night to mourn the loss of his former producer, Traxamillion.

“I’m still very sad that he’s gone,” Keak told me in my report for the San Francisco Chronicle last February around the time it had happened. He didn’t embellish his pain, didn’t mask how he felt. He was straight up somber.

Having engineered Keak’s ecstasy-and-cocaine induced hymnal, “Super Hyphy,” Trax was the flagbearer for Northern California’s spaceship-fueled sound, a seminal audio architect from San Jose, the oft-forgotten capital of Silicon Valley. Within the insular confines of the tech-and-vineyard bordered soils of the Bay, he was considered a music luminary.

Known for his magnum opus, Slapp Addict, Traxamillion was our virtuosic Lil Jon, our ultra-upbeat DJ Screw, our parochial Ali Shaheed Muhammad. He was a visionary and experimental orchestrator of sideshow soundtracks, who gave us figure eights in the form of elevated, bell-and-echo mobb music. He never strayed far from his collabs with local talent nor shied away from the idiosyncratic loop of Yay Area sound.

His loss felt — and still feels — like a collective blow. In a cluster of zip codes that men like Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk have plundered, losing an artistic icon like Trax can hit even harder.

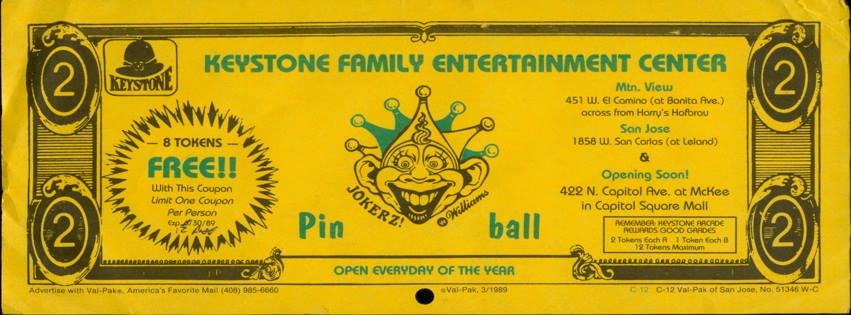

I grew up some miles north of Traxamillion. As a knee-high growing up in the Silicon Valley suburb of Mountain View, bouncing around from place to place along the 101, my brother and I would ritualistically get together with whatever crew of other immigrant-raised kids were living in our apartment building at the time. We’d hop onto our bikes — sometimes on pegs, sometimes on handlebars — and pedal ourselves over to the Keystone Arcade.

Even if we only had a few crinkled dollars, we’d split what we could and make the entire day stretch into joystick-twirling hours of Mortal Kombat, Killer Instinct, NBA Jam, NFL Blitz, Area 51, Time Crisis, The Simpsons, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Tekken, and everyone’s favorite, Super Street Fighter II. As the youngest in our group, I’d usually end up watching the older kids and grown dudes take turns in informal tournaments, delivering lethal combos of pirouetting punches and flying kicks until no one was left standing. I was never good enough to participate, but still, I felt a part of the group and of the larger community of gamers who were all willing to share a brief moment on this ever-expansive continuum together — something that feels harder than ever to do with complete strangers these days.

Image via Alan Chazaro

Image via Alan Chazaro

Like Trax, Keystone and every sacred, affordable space from my memory of the Bay Area in the 90s and 00s, no longer exists in the physical form. In an un-cryptic Facebook post from the San Jose-based company’s account during the height of quarantine, their bio shared an oddly sentimental, yet direct truth: “Remember the good old days, when fun could be had for just a quarter.”

Like Keak’s admission of sadness, the owners of Keystone revealed their unadorned emotion, a curt yet loaded phrase with an underlying sense of dread at the disconnected reality of modern living, when not a goddamn thing costs a quarter. For context, a current home in my former neighborhood averages nearly $2 million. The kicker is that they’re two and three-bedroom condos and apartments in a baseline middle class neighborhood that probably wouldn’t cost more than $250,000 in most other parts of the country. It’s absolutely not what you’d hope $2 million for a home in America could get you).

The clear reason for the inflation and for the earthquake-like shifts in the local culture and economy is that we live next to what has now become Google’s global headquarters – and just a few freeway exits from Facebook, Apple, Instagram, Netflix and just about any other technological app and major company that the world depends on. Those didn’t exist when I was growing up.

As a teenager, I was doing a lot of the regular mindless Bay Area shit like hotboxing Hondas with the same homies I hit up the arcades with: spray painting walls, causing juvenile destruction and participating in bootleg sideshows and backroad races. Except for us, a lot of it happened in the rapidly growing Silicon Valley, in parking lots of office buildings at nights where, at least back then, there was very little security or oversight and we could hop from building to building without any adult interference. In many cases, offices that were being newly built — or ones that had yet to be rented, or in some cases, had even been left unused for months — were especially good for our hyphy-era shenanigans.

Looking back, it all felt relatively low-stakes: a bunch of youth congregating together outside, exploring our environment, bumping Andre Nickatina and Hieroglyphics, hopping fences and hitting up hotel parties all over the San Francisco Peninsula. Later on, when I was 19, I moved across the Bay to Berkeley and never really looked back. But the South Bay remained a place of nostalgic joy and formative discovery in my mind, a peaceful corner amid the growing chaos of the world while the increasing cost of living pushed more and more of my friends and family out.

A few weeks ago, I finally left the East Bay and returned to Silicon Valley — now a father, a husband, in my 30s. I’m back with my pops in the town house he bought decades ago, when I was a high school freshman, and where he has lived ever since. There’s no chance we could afford to be living here in 2023 if it wasn’t for that stroke of luck and privilege my dad — a Mexican immigrant who never finished high school — had in purchasing the property at the right time and place before the market exploded.

Image via Alan Chazaro

Walking around my hometown nowadays is like revisiting an album I’ve spent my life listening to, but suddenly the songs are out of order with lyrics that are no longer relatable.

In the wake of hyper-gentrification, none of my friends or their families are left — replaced by legions of half-humanoid transplants who worship Tesla and never look you in the eye when you walk past them. And I don’t think there’s many residents left in my area code who could even name their favorite Traxamillion album.

I’ve been coping with it all by listening to a shit ton of Super Beat Fighter — Trax’s quietly released 2020 project that remixes the arcade game’s themes, sounds and characters into an instrumental album. It’s wordless, but somehow, the album has moved me more deeply than any other hip-hop offering I’ve heard this year.

The album’s cover art is as punchy as the music, depicting a Super Nintendo-styled Ken, who is dark-skinned and rocking cornrow braids. Chun-Li bends over a parked Lexus with the frigid waters underneath the Bay Bridge behind them.

From the opening basslines and 16-bit noises on “Title Screen” and “Select Yo Character,” to the last track “Bison’s” build up of confronting the final boss the album is more fire than Dhalsim’s yoga flame.

Far less celebrated than his epic singles — which include East Palo Alto duo Dem Hoodstarz’s “Grown Man” and The Jacka’s “Glamorous Lifestyle” — it’s an uncharacteristically minimalist and almost subdued version of a post-hyphy Traxamillion. Maybe he became more reflective and nostalgic about the losses around him. It might not be what he intended, but in hearing the lyric-less songs today, I feel them reaching back to a time when all of us kids who didn’t always see ourselves reflected in the dominant mainstream culture could live freely, enjoy ourselves without worry and find stitches of similarities among each other in our video games, our weird music, our enduring friendships.

Walking around these past few days since my return, I haven’t seen a single group of teenagers hanging out like my generation used to. How could they? It’s all been gutted and remade for the comfort of hyper-wealthy outsiders. Even worse, the baby-sized handful of teens I have actually encountered in my old neighborhood don’t seem to have any connection to Bay Area culture (their parents probably parachuted in as highly paid tech employees who don’t give a damn about what’s happening in the community). That’s sad as fuck to me. They don’t have a Keystone. They don’t have a Traxamillion. I wonder how long they will remain here, and who even has access to that sort of upbringing anymore.

As I wander these intersections looking for ghosts of my past, I make sure to slap “Zangief,” which opens with an arcade announcer declaring “U.S.S.R” and a sinister laugh, followed by a trippy, warped choir of singing children synchronized over the Russian fighter’s in-game background instrumental. That quickly switches over to “Guile,” a pro-America, bald-eagle soaring anthem with snippets of “sonic boom” and patriotic horns to accompany the U.S. Air Force pilot’s track. Other cuts deviate towards a calmer, more meditative interpretation. For “Balrog,” the game’s notoriously Mike Tyson-inspired, Las Vegas-based boxer, the vibe is surprisingly softer than one might expect for a man who uses “Buffalo Head” as his preferred defensive maneuver. (For what it’s worth, my favorite track is the tropical waves and flutes washing over “Blanka”).

In a society oversaturated with more noise than ever — and in a region like Silicon Valley, where there are self-driving cars and automated delivery bots crawling on sidewalks — it’s necessary for me to go back and revisit the simple, playful energy that Traxamillion left behind in Super Beat Fighter. It doesn’t feel empty and sprawling like Travis Scott’s latest music does to my ears. It doesn’t feel as if it’s trying to go viral like an Ice Spice social media clip.

Instead, it’s more like finding that long lost CD in your dad’s garage that you thought you’d never find again, but somehow, it found you — and sometimes that’s all you need.