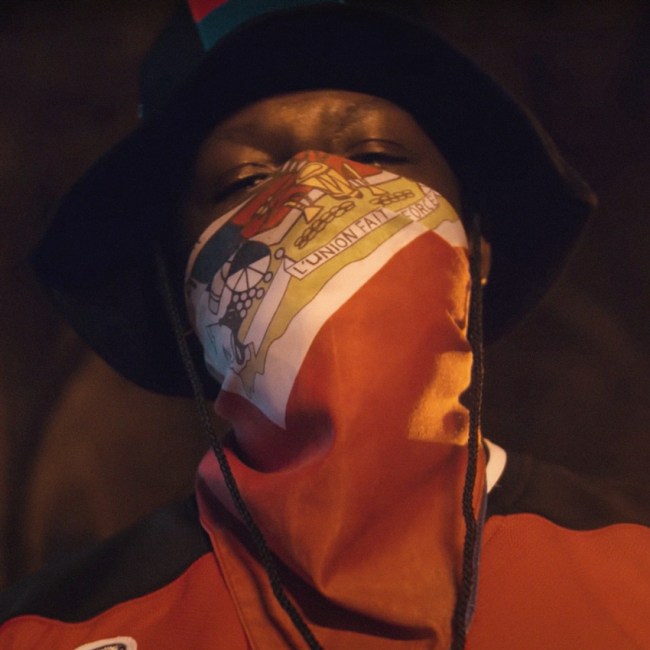

Photo via Griselda Records

Joel Biswas takes his business calls from the hot tub.

On “Au Revoir”, the triumphant crescendo of Mach-Hommy’s outstanding Pray for Haiti, the rapper is asked “where the fuck” he’s been hiding. It’s a nod to the fact that until very recently Mach-Hommy was as much an urban legend as he was one of rap’s most wildly original voices, scattering his prolific output across the internet at investor-level prices, concealing his true identity behind Day-Glo bandanas and eschewing interviews. But if this riveting, revealing record is anything to go by, Hommy hasn’t just spent the last few years rapping more effortlessly than most of us breathe – He’s been reckoning with the real cost of fulfilling one’s potential and carefully biding his time.

His formidable reputation rests largely on 2016’s precocious Haitian Body Odor – an 18-track epic that brought dense project slang out of cold storage like one of Michele Duvalier’s fabled mink coats. With a cinematographer’s eye and a novelist’s sweep, Mach’s icy threats and vivid explorations of Haitian identity brought a welcome Caribbean tilt and dose of anarchy into the staid formalism of revivalist New York-centric rap. First affiliated with Buffalo’s then fledgling indie imprint Griselda label, Mach appeared on Gunn and Conway’s debut EP Don’t Get Scared Now, ripping icy couplets but was gone before they landed gargantuan distribution deals with Shady Records and Roca-Fella. Since then, he’s returned to the dankest chambers of the underground, cultivating his air of haughty unpredictability, turning vinyl and merch sales into capitalist art and working with link-minded recluses like Tha God Fahim, Earl Sweatshirt and Your Old Droog. Projects like his run of Dump Gawd tapes with Fahim were drunk on stylistic innovation, relentlessly bending language and form over wonky beats but a true follow-up to a slow-burn classic seemed no closer.

The tantalising backstory to Pray for Haiti is Hommy’s unlikely return to the Griselda fold. It’s a surprisingly obvious move for an artist who reflexively confounds expectations and one that reflects newfound impetus. Westside Gunn plays exec producer, assembling a plush array of new bap grooves heavy on analog lustre and light on drums and briefing Mach to “fuck up they top five,” which is precisely the Newark MC does every bar of the album’s breathless 40 minute running time.

At his best, Mach is both savagely funny and preternaturally vivid. On opener “The 26th Letter”, he bounces of off a taut loop of traditional Haitian Rara music and demands his flowers in the form of a python trench coat. “No Blood, No Sweat” shouts out the day-one fans (or “investors”) who pay Sotheby’s prices to own a small piece of his art and then signals his intention to continuing building with his day-ones Westside, Your Old Droog and Fahim (“The rest is dickblowers.”) On “Makrel Jaxon”, his whole team rolls up “in mink coats/ Links looking the water in sink froze/ still got my Andrei Kirilenko’s”. Over an indelible RZA-style loop on “Pen Rale”, Mach goes from garden variety diss to meta-linguistic deconstruction in two bars: “Don’t forget to kiss the ring, you might live through another elliptical dip into…. I’m in my bag n*gga… I’m very instrumental.” Beyond his protean lyrical ability, Hommy’s warm baritone and singer’s ear for melodic inflection bring airiness to his songs and occasionally claustrophobic writing. He croons the hook of “Murder Czn” with exaggerated menace before bringing a dancehall swagger to his lines, adding a gospel swoon to his wealth-seminar exhortations that recalls Mos Def and Wyclef in their prime.

Pray for Haiti’s urgency and focus are fuelled by unvarnished recollections of what it takes to earn a spot. Early on, he’s momentarily back in the sweltering trap house, ruefully acknowledging that “he had to dumb it down on my slow 50 Cent flow” just to get back out. “Kriminel” is an exorcism of demons both personal and literal. Mach hates the industry but he needs it because his mission is bigger than himself, extending to his Haitian kin in the broadest sense (“N*ggas’ feelings need songs, stuck in facilities of memories gone.”) as well as close family (“my cousin Jameson on the chat telling me to send that fucking money before he crack”) “The Stellar Ray Theory” is a potent study of what it takes to survive in those shark-infested waters. Over sultry neo-noir sax and marching kicks, Mach quotes Raekwon, Ghostface and Jay Z as he recalls hustling his music on obscure e-commerce sites and overcoming failed music dealings in LA. Rap is a mental game where for most, “if the sun don’t shine/ Then son don’t shine,” a domain where hardships reveal character, wash away pretence and where those who cannot see their own agency in their failures are soon banished.

“Marie” is a rapt, hallucinatory tryst with the fairer sex where Mach adlibs in Creole before dropping two weightless Outkast-inspired verses and then deliciously plundering a Tupac hook as he veers between lust and reverence. He hasn’t forgotten his love for the thorniest avant-garde rapping either; Fahim pops up on “Magnum Band” while the lysergic “Foli A Deux” recalls Mach’s dusty, liminal experiments with DJ Muggs as Westside Gunn’s verse strains to keep the song from drifting into the ether. The usually flamboyant Gunn is an understated guest and sympathetic compère throughout, recognising that Mach’s wild energy is a welcome shot in the arm for a steely commercial behemoth, even if Mach was once far more than Griselda could have bargained for. He acknowledges their history gracefully when he raps, “I messed with the moon and came back with the sun.”

“Au Revoir” is a sun-drenched victory lap and acknowledgement of exactly where Mach finds himself. He’s gone from sampling the elders to breaking bread with Jay Z; from selling CD’s on Instagram to giving 20% of his masters to a foundation he’s set up for his native Haiti. He’s already given as many interviews since the album’s release as he did in the previous five years, secure in the knowledge that he “earned his seat at the table without shucking and jiving.” Pray for Haiti is that rarest of things – a rap record that’s both a treatise on and testament to greatness, a high water mark for an artist who is still in the ascendancy, at last ready to let the mask slip and be seen.