How Rick James & His Hardworking Band Crafted His Breakthrough Album ‘Street Songs’

In celebration of the 40th anniversary of Rick James’ Street Songs, we spoke with engineer Rick Sanchez, who provided an incisive account of how this classic record came to fruition.

Coming from humble beginnings in the Perry and Willert Park Projects, located in Buffalo, New York, James Ambrose Johnson, Jr., better known to the world as Rick James, found his musical gift at an early age. While growing up there, he unearthed a knack for creating music with random household items. By the time he was in elementary school, he was singing in the choir at St. Bridget’s Roman Catholic Church. Under the tutelage of local minister Reverend Malcolm Erni, he began learning how to play the bongos and congas. Once he entered Bennett High School, he joined the school’s band and sung with two of his closest friends, Jimmy Steward and Levi Ruffin. Shortly thereafter, he joined the Naval Reserves at the age of 15 to avoid being drafted into the Vietnam War.

Johnson always had a zest for living the fast life. And as a teenager he found the military to be too rigid so he fled to Toronto, Canada, where he befriended two unknown musicians at the time, Joni Mitchell and Neil Young. He changed his legal name to Ricky James Matthews to avoid military authorities. A few months later, he formed the Mynah Birds with Neil Young. As their popularity grew, the band was signed to a record deal by Motown Records in 1966, but they never released any material because James was arrested for deserting from the Navy two years earlier. Around this same time in Detroit, he performed an impromptu version of “Fingertips” in front of Stevie Wonder, and Wonder suggested he change his stage name to Ricky James. A few months later, James served his one-year prison sentence throughout 1967. Between 1968 and 1972, he produced songs for Motown acts The Spinners and The Miracles, relocated to California and then the UK, and continued performing as a bassist with various rock and funk groups he formed or joined.

By 1973, he signed another recording contract with A&M Records. He recorded his first solo hit, “My Mama.” Three years later, he formed the Stone City Band in his hometown. In 1977, James and the band signed a record deal with Motown Records’ subsidiary label, Gordy Records. The following year, he released his debut album, Come Get It!, and the album achieved gold-selling status. In 1979, he released two more gold-selling albums, Bustin’ Out of L Seven and Fire It Up, establishing him as the extension between Parliament-Funkadelic and Prince. During this juncture, he began working with legendary engineer, Tom Flye and his young assistant engineer Rick Sanchez. This unit would prove to be critical to James’s groundbreaking success in the coming years. At the beginning of the new decade, he recorded his fourth consecutive gold-selling album, Garden of Love. In 1981, James would be catapulted into superstardom with his next studio effort.

During the recording phase of his next album, he began tinkering with state-of-the-art recording equipment and interweaving different genres of music to create his original punk funk sound. Alongside James was Sanchez, who joined him from Record Plant Studios. His experience became a valuable asset while assisting Flye by setting up the recording equipment that captured James’s infectious talent and energetic persona.

On April 7, 1981, Street Songs was released. It peaked at number three on the Billboard charts. The album spawned two chart-topping singles, “Give It to Me Baby” and “Super Freak.” In celebration of the album’s 40th anniversary, we spoke with engineer Rick Sanchez, who provided an incisive account of how this classic record came to fruition.

How were you chosen to become involved as an engineer on this album?

Rick Sanchez: Well, Rick [James] was a music fan and a history buff. He was a huge Sly Stone fan. Sly had recorded at the Record Plant, and he had his own studio at the Record Plant in Sausalito, California. I think that’s why Rick decided to come there, mainly for the vibe and because of Tom Flye. Tom Flye was the chief engineer up there, and I was Tom’s assistant for many years. When he came, he said, “I want to use the same people and get the same vibe as some of those Sly things.” Sly was another person who was able to take so many different musical styles and combine them into something completely different. You can hear a lot of it in some of Rick’s arrangements where he would use classical baroque kind of things. Funk, classical, R&B, and hard rock stuff with Tommy [McDermott] playing guitar. He loved to combine all those different styles.

During the making of Street Songs, can you describe the studio atmosphere between Rick James, the band, and the engineers?

For Street Songs, we set up a bedroom for Rick at the studio. There was a shower, a jacuzzi, and a conference room that we turned into a bedroom. It was right next to the studio. He stayed there the whole time. Sometimes he would just say, “OK, I’m going to bed. You guys do the editing.” At that point, it was usually either Danny [LeMelle] or Levi [Ruffin] taking over the production process unsupervised.

What was the collaboration process like between Rick James and the other band members?

Rick would come in and he would have sketches of songs together when he came into the studio but nothing was complete. Rick liked to be in the control room because he liked to have the monitors on, and we’d set up a handheld microphone for him in the control room. They would start on the groove out in the studio. Levi would be in the control room usually with a synth. The keyboard player, Nate [Hughes], was usually out there. Lanise [Hughes] was playing drums. Oscar [Alston] would set up in the control room usually with his bass. Danny [LeMelle] would be wildly taking notes the whole time. They would start a groove going, and Rick might sing a part to them. Then, Oscar would change the bassline around a little bit. As they were doing that, we would be rolling either a two-track tape, or sometimes 24 tracks just to catch ideas. When they got a groove that they liked, and when Rick was happy with a groove, then he would start improvising vocals over it. Once they got that done, he would start putting the song together lyrically. A lot of times the original lyrics were nonsensical, but he would get the phrasing and the melody down. Maybe he would come up with a hook, or a vocal line like “Super Freak.” “Super freak” was a throwaway line that ended up turning into the song.

What was the band’s typical studio routine during the making of this album?

[laughs] There really wasn’t any set schedule. With Rick, it was when he woke up he’d start working. There were many times where he would go until he couldn’t work anymore. During one session, we didn’t take a break for 36 hours. He would get a lot of work done. It was kind of funny because, at times, it would seem very chaotic because he also loved to have an audience. Whenever there was an audience there, he’d have six or seven people in the control room that weren’t part of the band. They were just friends. There was a private Rick James, and then there was the public persona Rick James. Whenever he had an audience, it was always the performer personality of Rick James that would come out. It was interesting to see because, if you were one-on-one with Rick, he was usually very different than when he’d have an audience. He would open up a little bit more. He would talk about personal things. He would talk about his life.

He really loved to perform. I think, sometimes to his detriment, the lifestyle of the public performance took its toll on him. That he always had to be on when he had an audience. He could talk about anything from politics to world history. He was very well-read. Obviously, he had studied a lot of history. He didn’t really let that side of himself come out that much in public.

How would you all handle the setup duties for getting the studio ready for each recording session?

Anytime there was a session coming in, Tom and I would discuss what type of sound he wanted to go to. Now, Tom was an incredible mentor because he was a guy who could work with anybody. No matter how chaotic a session would get because, in many ways, Sly and Rick had a lot of similar personality traits, where their minds were working so quickly, and their ideas would be coming so fast, that it was hard to keep up with them. Rick would have an idea for a bassline, and then all of a sudden, a clap in that line would come into his mind. Before he would forget it, he’d want to get it onto tape. So, we pretty much had everything ready to go. We even had set up some horn mics just in case Rick said, “OK, we need to do background vocals, or we need to do horns right now.” He wanted to be able to capture it as soon as possible. We would have the synthesizers plugged in and ready to go. We’d have microphones, even if it was just a rough mic.

Tom figured that out probably within the first two or three days of working with Rick. I think, on the third day of working with Rick, he said, “I want you to have the microphone in the control room. I want to have the bass set up in the control room and a bass setup out in the studio.” Because sometimes when they were first rehearsing the song, everybody would be out in the studio. Then he’d say, “Let’s go into the control room.” We would set up a mic in the control room and sometimes Rick was just screaming directions like, “Do a funk thing here.” Or “Guitar, do a funk thing.” He would be talking into their headphones through his microphone, and then when he was comfortable with a groove, he’d start riffing on vocal parts or on melody parts. We always had at least a two-track going to capture ideas, just in case there was something that made him say, “Hey, I had an idea a while back. What was that?”

What was some of the equipment you all were using to capture the sound for the album?

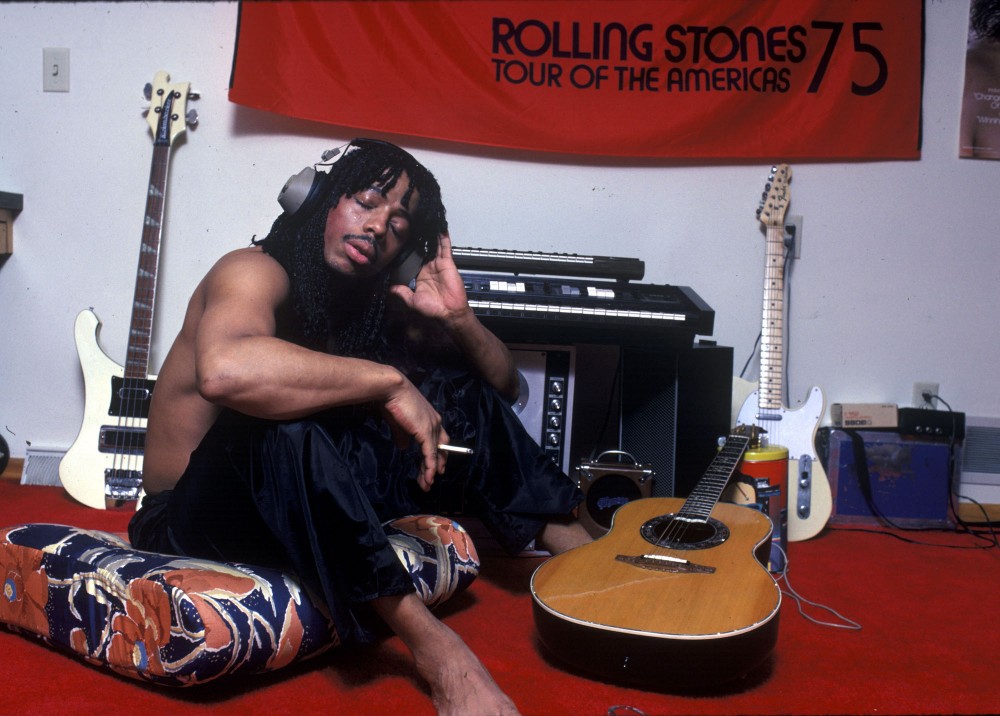

The bass was almost always just direct, and it was almost always a Fender Jazz Bass or a Fender Precision Bass. In a lot of the photos, he was playing a Rickenbacker Bass. There are a lot of photos of Rick with a Rickenbacker Bass, which I think he would occasionally use on stage, but in the studio, it was almost always a Fender Bass direct. The Fender Rhodes was always there as was a grand piano. It was funny because Rick could play a lot of instruments. None of them great, but he could get a feel for it. He knew how to put a feel on something, especially on things like bass parts. He might come up with something, although he couldn’t really execute it, he could communicate the feel and then Oscar [Alston] would go and say, “I think this is what you want.” And Rick could say yes or no.

Rick James usually played Fender Jazz Bass or a Fender Precision Bass. Photo Credit: Paul Natkin/Getty Images

What was it like working with the Mary Jane Girls when they were doing the backgrounds?

They were great because they loved to sing. I don’t think that they had done an album on their own, but he loved the idea of possibly putting together a girl group at some point. I don’t think that had happened yet. The Mary Jane Girls’ album [Mary Jane Girls] maybe happened right after that. He loved both horn parts and background vocals, and he had a lot of fun doing that. I think the Waters sisters came up on a couple sessions, and they were fantastic. They were the session singers that sang on some of Stevie Wonder’s albums. They were an LA group and would sing on everything. One of the things about the Record Plant was there was a lot of collaboration going on. There was also a friendly competitiveness between a lot of the artists that would play in there. This is where he met Narada Michael Walden. Narada came down and was working on a session, and he ended up coming in and playing drums on “Make Love to Me.” He would love to have other musicians come in and listen to his stuff. Lots of times, if he saw that they were really liking it, he would say, “Hey, let’s put you on this.”

Stevie Wonder also played harmonica on “Mr. Policeman.” What was that experience like watching Rick James work with Stevie Wonder?

I wasn’t on that session because I think Tom [Flye] and Rick flew down to LA probably for a Motown meeting to find out how the album was going. They went for, I think, two days, and that’s when they ran into The Temptations and Rick said, “Oh, I got to get The Temptations on this.” The Temptations sang and Stevie Wonder also came in. I believe that they did that stuff at Motown Studios. Stevie Wonder was always around.

If someone were to walk into the Record Plant where you all were recording, what did it look like at that time in the early ‘80s?

It was still very Northern California. The studio was psychedelic. There were tie-dyes and curvy mirrors. The walls had some velvet on them. There was great lighting in the studio, so you could really change the mood. It had different colored lights. Of course, the Record Plant was known for doing whatever the client needed to make them comfortable. If they wanted to paint the room a different color, they’d do it. If they liked certain colored lights, they’d do it. On a couple of his vocals, we kept his scratch vocals which were just on a handheld mic, but most of the time, he would sing with a nice Neumann or something like that out in the studio. He liked to have a really nice Persian rug set up, and we’d have a little table set up with Courvoisier or Hennessy on it. We’d have a spotlight for him. We’d have a red spotlight and set it up for a show. Depending on the song, sometimes it would be really bright. Sometimes for the ballads, we’d do mood lighting. For each song, we might change it up a little bit. Again, we’d like to have everything to go as quickly as possible because Rick might wake up at 2:00 am and say, “I have an idea and everybody get in the studio right now.” And everybody would run to the studio.

I remember on “Super Freak,” they recorded the main groove for 20 minutes. I think we had a full reel of tape with just that groove on it. He said, “It needs to be so tight. There can’t be anything off in this song. I’m going to bed. You guys stick around and find the best eight bars and that’s what I want.” We listened to it. I think it was just the guitar, bass, drums, and maybe the Fender Rhodes. We found eight bars that was just completely locked. Tom said, “OK, here’s what we’re going to do. Set up another 24 track, and we’re going to copy that eight bars multiple times.” Then, we took that eight bars, and we edited it into the song. It was basically like you would do with looping today, but it was done by cutting tape.

That’s amazing. You have to be incredibly precise when cutting tape.

Yes, that was one of my first really big nerve-racking jobs where Tom said, “I’m going home, Ricky. You cut this thing. Call me in the morning when you have it done.” We were there from like 2:30 am until about 8:00 am.

It’s funny, because at first, “Super Freak” was not going to go on the album. Rick said, “I don’t know if that song’s strong enough.” The band loved it, and I don’t know if it was the record company that was a little bit unsure about it. A few people came into the studio, and when they heard it, they just said, “Oh, fuck. That is fucking great.”

How long did it take to record this particular album?

Street Songs didn’t take that long. It was maybe three weeks. They had just finished a tour, because I remember when they showed up at the studio, a truck pulled up and it was a tour truck that still had all their equipment on it. [The band was] always working. Eventually, Rick built a studio in his house in Buffalo [New York] and I only went out there one time. Tom Flye ended up almost moving out there, but he did have a nice studio in his house in Buffalo. At the Record Plant, I think we recorded Fire It Up, Garden of Love, Street Songs, the Mary Jane Girls album, and two Stone City Band albums. We did quite a bit of work with Rick.

Because you worked with him for years, you were really familiar and in sync with the whole band.

He really did like the family atmosphere of the band because they were all very tight. I know that there was a bit of a falling out later on over probably financial things and stuff like that, but a lot of them were from Buffalo, and they knew each other really well. I remember one time he was missing Buffalo, and he had a five-gallon thing of buffalo wings flown in from his favorite bar in Buffalo.

Could you talk a little bit more about how in sync they were for this album, and how much that made a difference in terms of the sound?

The band all lived in Record Plant house together, so they spent a lot of time together. They were always on the road. If they weren’t on the road, they were in the studio, and so they really knew each other. Of course, when you’re with people that much, it’s just like a family. You’ll have little spats about certain things, but they always seem to work it out. Levi [Ruffin] was almost like the psychologist for the group. Whenever there was tension, Levi would find ways to smooth things out. Rick, when he was in a bad mood, he could be tough. If he didn’t like something, he could be very vocal about it. Sometimes not in a diplomatic way. I’m sure that hurt sometimes because they were very loyal to Rick. Levi could be like a psychologist and could say, “OK, calm down. Let’s go for a little walk. Let’s go smoke a joint.” Or, “Let’s take a walk and play some video games out in the game room.” Then, Danny was, of course, the arranger. Danny really would help to hold it together musically.

There was Tom McDermott, who was the rock and roll guy. Tom was always wanting to really go out on the edge and try different things. There were a lot of times Rick would say, “OK, you guys. I’m going away. You go find some guitar parts.” He would say, “I want you to rock this up.” Tom spent three or four hours trying to find a new guitar sound until 2:00 am. Eddie Van Halen was just coming into this thing. Tom loved Eddie Van Halen. We tried different types of guitar parts and things like that. It was a very experimental time. Towards the end of “Super Freak,” Rick was beginning to get big so some of the musical instrument companies would start sending synthesizers over. At that time, they used a Crumar synthesizer, which was not a great synthesizer. It was a cheesy string sound thing but Rick loved that sound. It was also the very beginning of drum machines, so we would start experimenting a little bit with the drum machines. There was a TR-808, I think.

We had found one of Sly [Stone]’s old drum machines. Sly had a thing called Maestro Rhythm King, which was the type of drum machine that they had on organs back in the ‘60s. It was really cheesy sounding. You could hear it on some of Sly’s records. He heard that Sly used this, and he said, “Oh, get me that thing. I want to try that.” He had come up with a beat on it.

Rick James’ 1981 album, Street Songs, catapulted him into superstardom. Photo Credit: Gordy Records

Were there any other famous folks who came by the studio to listen to what was being created by Rick and the band?

One of the most interesting things was Sly Stone came by. Rick was very nervous about it. He really, really admired Sly. Rick also thought of himself as the next generation of Sly Stone. Rick really wanted to be the crossover of crossovers, which is the punk-funk part of it. He wanted to be rock and roll, and he wanted to be R&B, soul, funk, and pop. That was his goal. He was very competitive and, of course, so was Sly.

Watching the two of them was like watching a couple of caged tigers meeting for the first time. It was very interesting to see the dynamic. Of course, it was very cordial. There were many times that you could see that both of them were nervous because they did have the same type of audience where they were crossing over. Part of this was during the time when MTV wasn’t playing any Rick James music, which was ridiculous because he would have been great on MTV. He loved being in front of a camera. I know that he was very pissed off about that and rightfully so. He never got the boost that exposure would have given him. I think that led him into a little bit of a downward spiral. He was very angry about that. It was really hard on him. He really wanted to be the first big Black artist on MTV.

How did “Ghetto Life” come together?

As far as I remember, this may have been the first song that we recorded. I remember that the drum beat was where he said, “There’s too much hi-hat. Get that hi-hat out of there.” Finally, Rick just said, “Cover the hi-hat with the blanket.” I remember Tom, the guitar player, was in the control room. They were singing the horn part. That was something that Rick was actually singing. Danny [LeMelle] was writing that down and ended up turning it into a horn part because, originally, Rick thought of that as a vocal melody. “In the Ghetto” was the line that he had. He sang the melody but it was nonsensical lyrics. Once they had the groove down, Rick would take off, and he would go into his bedroom and start honing the lyrics. Then, he would come back and sing the lyrics, but it started off with him just riffing ideas with “in the Ghetto.” Some of the lines, he would find little bits and pieces out of that original riffing that he would expand on and turn them into the lyrics. I remember he was talking to us a lot, and I think they had been on the road for a long time.

He loved living in Buffalo. He loved the people, and he was a hero there. The Buffalo Bills all knew him. He had the love of the town when he was there. I think he had been on the road for so long. He was missing it. On “Ghetto Life,” he was singing about his town. He met a lot of the guys in the band in Buffalo, and they really were just hanging out musicians. Eventually, they turned into the band. It’s an autobiographical song.

How about for the next song, “Make Love to Me”?

This was the one that Narada [Walden] played on. The strings were all done in LA, too. The weekend they flew down and recorded The Temptations, the string parts were all put on down there too. Things like the horn and the string parts, those were very collaborative between Rick and Danny. Where Rick might sing a part, then Danny would expand on them and come up with the harmonies. That was a very interesting relationship between the two of them because Danny definitely was the Quincy Jones of the band. He really knew all the arrangements and could read and write everything out. He was very quick at coming up with arrangements. I remember we started this one very late at night. It must’ve been 2:00 am. We were really tired. He said, “OK, let’s do something slower.” He was worried that doing something slower would put us to sleep. The Fender Rhodes piano part was really nice on there. Oscar’s playing was really good on this one. We recorded that vocal at 4:00 or 5:00 am. It may have been just Rick and Tom Flye and Levi Ruffin working on that vocal. It was very, very dark in there. There was just a dim red light out on in the studio when we did this one. There weren’t a lot of takes. The vocal went down very quickly, but I think that is actually one of his better vocal performances.

What about “Mr. Policeman”?

I remember one night we had a night off, and we were going to go out. I don’t know if you’ve ever been to Sausalito, but Marin County is very white. It’s a wealthy community. The studio was right down by the bay. There was this big hill that went all the way up to the mountain. It was right across the Golden Gate Bridge from San Francisco. I remember we were all going to go out to the city to see a band. We got into a car, and we pulled out onto Ridgeway, and we immediately got pulled over by the police. They had a really nice, big Lincoln Town car. Coming from Buffalo, the police could be pretty rough there. It really put a damper on the evening, and we ended up just immediately turning back. It got just weird enough that it was scary. The cops asked us, “What are you guys doing?” “What are you guys doing here?”

Luckily, I was in the car and there was one other person from the studio in the car. We answered the cops, “We work at the studio here. We were just going out to get something to eat and going back to work.” We ended up not going into the city because it was a scary thing. It was one of those things where it was obvious why we were pulled over. We hadn’t done anything wrong, but at the same time, they were recording the song, “Mr. Policeman.” They had recorded it, and it was a little bit of a reggae groove. Levi [Ruffin] was telling me stories about some of the experiences that they had with the police over their lives.

As you look back 40 years later, what are some of your fondest memories of working with Rick James?

Those albums took a long time. They would spend a couple of months in the studio. Rick would get to work and part of that was he knew that studio time was expensive. He would lock out the studio. He had it 24 hours a day, but he didn’t want to waste any of that 24 hours. While the bands that would do lock outs, they would go in and work for six to eight hours, and then the studio would be sitting empty the rest of the day because they had it locked out, but they were paying for that time. For Rick, if he wasn’t going to be there and needed rest, he would have something going on, whether it was saying, “You guys put down guitar solos and then I’ll come and listen to it in the morning.” Or, “Danny, you work out parts.” Or, “You have the bass part now. You know what I want. Make it perfect now.” Afterward, he would just leave. He didn’t waste time in the studio. The few minutes when you would have alone with Rick, you could see how he would relax and turn into a different person when he was not in the Rick James mode. He was a lot deeper than his stage persona.

It was tragic what happened to him. You see that with a lot of artists that the lifestyle overtakes them and there’s always people trying to use them when they’re famous and rich. There’re always people trying to take advantage of them, but Rick was pretty smart that way. He had a lot of street smarts. He could tell when somebody was trying to use him, and I think that’s why he loved his band so much because they really were loyal to him. At some point, drugs and alcohol can mess with your mind. It was sad that it did, because I suspect, if he would have gotten clean and had a manager who would have really watched out for him and kept some of the people that were bringing him drugs and things away from him, we would have heard a lot more from Rick over the years.

__

Chris Williams is a Virginia-based writer whose work has appeared in The Guardian, The Atlantic, The Huffington Post, Red Bull Music Academy, EBONY, and Wax Poetics. Follow the latest and greatest from him on Twitter @iamchriswms.