Graphic via POW

Ant shall bring disaster to evil factors.

I’ve never known a world without Lil Wayne. I was born in October of ’97 while he was two weeks away from debuting alongside his surrogate brothers The Hot Boys with Get It How U Live!, a record that would sell over 300,000 copies setting up the quartet to be Southern rap’s Backstreet Boys. In the 8th grade, I convinced my mom to call a local radio station to win a free copy of the multi-platinum Tha Carter IV on its release week. My Summer ’16, that blessed first summer after high school, was defined as much by Tunechi’s run of 2 Chainz collabs as it was the Soundcloud classics that mimicked the swag and mindless inebriation of his peak years.

Wayne was the archetypal mainstream rap star, but in large part he became this icon in spite of a disdain for the larger bureaucracy of corporatized music. He’d take his time getting to concerts, and interviewers would wait hours to get the honor of squeezing articles from pithy responses. His rollouts were unfocused messes, and he shrugged off the gravitas of the major label album choosing instead to splatter out ideas as they came.

During daily marathon studio sessions, peak Wayne recorded songs to be bundled up by DJs and producers with only loose guidelines. The true thrill of the Lil Wayne experience was living life one couplet at a time. The vital throughline for Wayne’s career was and remains process–the literal act of creating something from the frizz of neurons firing in the booth. Every YouTube ripped instrumental, every reimagined hook, every blunt blown between takes, every toilet bowl punchline, and every Gillie Da Kid clash were all side quests when compared to his Tha Carter series.

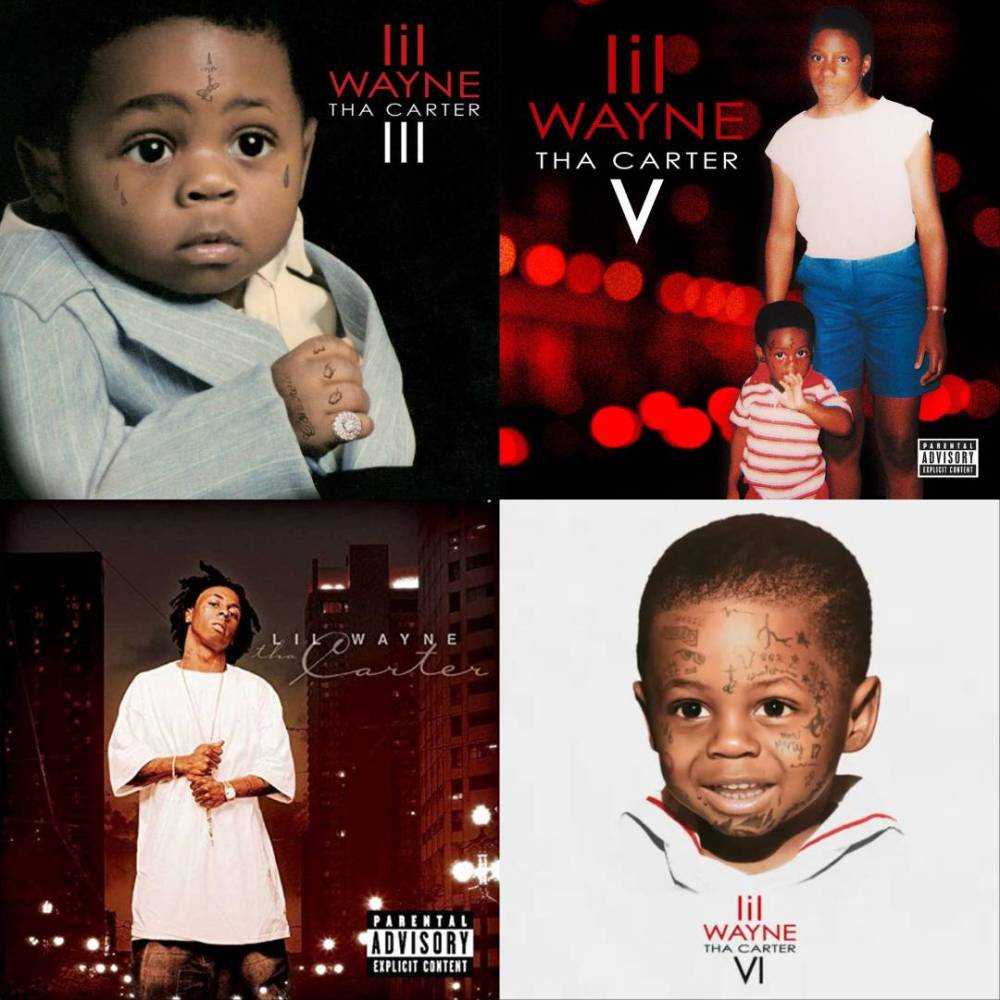

Since 2003, the North Star for each Carter project was to supersede any expectation, peer, superior, or rising challenger. They were never vibe-guided experiments, they were consciously crafted tectonic realignments of Wayne’s place within the greater musical landscape. Tha Carter‘s many entries intentionally pivoted him from Southern wonderkid to respected craftsman, smoked out rap gladiator to family friendly late night TV guest, and from a mixtape maestro to a musical deity.

It’s currently June 2025 and Wayne is still a global icon pushing his newest album, Tha Carter VI. Revisiting each previous Carter project puts his storied career in a more refined context as the realities of this newest edition still washes over us. Looking back reminds us that Wayne isn’t just a cloudy phonic alchemist, but a hyper-competitive savant calculating the perfect formula to seize the world.

During an interview on Talib Kweli’s podcast The People’s Party, Mannie Fresh, the Cash Money Records workhorse producer and zany absurdist half of the Big Tymers, recounts a conversation he and Wayne had in a Dallas club one sweaty night in 2003 before the duo began Tha Carter sessions. Wayne was serious, huffing to his mentor about his goals; “Bro I’m going a whole different direction, none of that kiddie shit. I can really rap. No more of them childish ass beats, bring your A game.”

Weezy’s frustration was understandable. His previous albums Lights Out and 500 Degreez didn’t connect the way his debut, Tha Block Is Hot had. Platinum was the bar and he was hardly scraping together gold. No one cared he was the teen that popularized “bling bling,” a phrase so powerful Merriam-Webster had to adopt it for its pages. The novelty of youth wore off as he added tattoos, grew a quarter inch or so, and dropped a couple of flaccid singles. Stylistically he’d stagnated, and he knew it, but his confidence never waivered. Also at this time, Wayne became the last man standing on Cash Money: Juvenile left for Atlantic Records, B.G. ditched the bright lights for indie hub Koch, and Turk found a new home at eOne, with each citing money troubles and interpersonal tension with Birdman as their reason for breaking ties. Wayne, the baby of the crew, with his rap brothers gone, had to become the man of the house.

The months following that club rant were a tennis match between Mannie and Wayne; a song would be “finished” together overnight, Mannie would pump up the production the next morning, Wayne would re-write his verses to match Fresh’s new flares, and a whole new record would be born from their competitive flames. Internally Wayne had planned for this project to be his last hoorah with the man who until that point produced nearly every song he’d ever rapped over. Perfection was the only way the duo could ride out.

In June 2004 Tha Carter was pressed up and released to the world, serving as his original rebirth. Over 21 tracks Wayne mastered the charismatic corner boy persona that Southern rap would revolve around for the next decade. The album had hits (“Go DJ”, “Bring It Back”), heart (“Miss My Dawgs”), a steadfast dedication to the street code (“Snitch,” “The Heat”), mystifying drug dealer tutorials (“Who Wanna”) and even a lil something for the ladies (“Earthquake”). Flows matured from beeline sprints to a mercurial trick box where changes in speed, tone, and tenor came every few bars. It was as much a collection of block party knockers as it was a slick talk clinic. With the “On The Block” skits and the “Walk In” / “Inside” / “Walk Out” suite he flashed a conceptual mind, using these interludes to build his home as a tower of crime and survival akin to the New Jack City project building of the same name.

Within a year the tape sold over 800,000 copies, and today is certified 2x platinum with “Go DJ” standing as his biggest hit until “Lollipop” rerouted the sands of time (more on that later). It also lapped the critical acclaim and success of nearly every previous Cash Money recording. He was no longer the young buck making the most of his sanctioned 16 bars, he was a bonafide soloist capable of carrying the torch. The next question over his head became, “What did you mean by that best rapper alive line?”

In December of ‘03, Jay-Z had announced his retirement from rap music. It was a lie, but for a little while Hov played off his Michael Jordan cosplay as reality. On the lead single for Tha Carter I, “Bring It Back,” Wayne refers to this marketing ploy, calling himself “the best rapper alive since the best rapper retired”. While C1 may have been a sea change for Wayne’s career, he still wasn’t viewed to be in that top class of MCs.

Right before Jay hung his Yankee fitted in the rafters 50 Cent had broken the pop culture space-time continuum with Get Rich Or Die Tryin’. Rap, and its capital city was in flux thanks to the power vacuum Jay left behind along with the system of infighting he and 50 caused. Simultaneously Kanye became the chart-topping new face of rapper-producers, T.I. was holding down the King Of The South title, Nelly went triple platinum in 3 months despite dropping the 2nd worst double disc in rap history (here’s lookin’ at you Lil Flip), MF DOOM released 70% of what would be an iconic catalog, and Eminem was filling stadiums while trying reallllyyyyy hard to be worse than Nelly.

Wayne needed more to break through the chaos. The rap world was for the taking and another boldly Southern record wasn’t enough to do it. Wayne wasn’t interested in being the King Of The South, he was going for King Of The World like his idol, and that meant shaking off his regional signifiers to do something universally understood; blacking out on every beat he could find.

With relatively unknown beat makers T-Mix and Batman replacing Mannie Fresh as his lead producer, Wayne was unbound. Sonically Carter 2 was a jukebox; soul samples, reggae adjacent anthems, grinding guitars, skitzo synth kaleidoscopes. For 77 minutes he emptied the clip; “Tha Mobb,” “Fly In,” “Fireman,” and “Money On My Mind” all with hardly a hook in sight. He introduced us to the hotboxing king of cool in Curren$y, imitated gun sounds with Kurupt, and there’s always the obligatory Birdman song. There was nothing he couldn’t do.

Energy wise it was a downshift from unchained hunger to swagger, from coded entendres to plainspoken similes and conversational streams of thought. To be the best, he had to act like the best. Blunts were lit with $100 bills, designer jackets were treated like Pro Clubs, and the faces of fans and women all blurred together with nothing but whispers of their adoring energy left behind. Leaning in the backseat of his Rolls Royce the world was flying by, and more than anything he wanted to capture this whirlwind ride to the top.

One of the few chest-pounding statements was “Best Rapper Alive”. The holy choirs and grinding guitars mimic a man preparing for war, asking God for protection as the blacksmiths sharpen their spears. Once settled he’s eating rappers alive while gambling a nest egg on a single football game, swiftly covering his face just to shoot off yours, embodying the Boogieman while playing Jazz Fest, shimmying into the ether before returning for a victory lap on your grave. It was a coup and coronation all in one.

Tha Carter 2 doubled the sales of its predecessor and was showered in critical acclaim, with many still claiming it as his opus. Off a calculated rebrand and overpowering penmanship Weezy made it into that elevated penthouse suite where only the most adored and popular rap stars could kick their feet up, but it still wasn’t enough for him. There was more to conquer.

Now the floodgates are open. Calls from Outkast, Destiny’s Child, Lloyd, Enrique Iglesias, Playaz Circle, Vibe Magazine, MTV; Lil Wayne had become a golden ticket for your lead single to get radio play, for your magazine to get swiped off shelves, for viewers to tap into your video countdown shows. Every few months a new track hit the blogosphere featuring Weezy F. Baby jacking your favorite rappers’ beat as his own and running wild on loops of golden oldies. The problem was, many of these tracks were never supposed to see the light of day.

From his first Sqad Up tape in ‘02 until the release of C2 14 lengthy mixtapes were officially released. Wayne had built a fanbase that was OK with using their hard earned cash for a CD every few years as long as their iPods were getting filled for free inbetween. It was this digitally fluent audience that made the impending leaks that much more detrimental. It wasn’t just a few bootleggers getting their paws on demos to be hawked at flea markets. Online compilations of to-be lead singles and A-side heaters flooded the internet, getting gobbled up in the hundreds of thousands; “Showtime,” “I Feel Like Dying,” “Scarface,” tracks with Kanye, Swizz Beatz, and Dr. Dre. The silver lining was it proved even Wayne’s most ambitious mutations had a wide-ranging audience. A famed studio rat, Weezy would cloister away with endless beat files from a who’s who of hitmakers to replenish his stash of songs.

For 16 songs he would cull the sprawl of his decade-long career for his riskiest moments, further pushing them to the edges of reality into dimensions unknown. It was a statement record about creativity in a mainstream landscape left barren by ringtone raps and previous giants running out of steam. “A Milli” was a supercharged “Money On My Mind,” “Let The Beat Build” accumulated the essence of all the soul looping leaks into a giggle-filled 4th wall break, “Dr. Carter” mastered backpacker jazz rap so perfectly Aceyalone could be found roaming Leimert Park kicking himself for months, “Mr. Carter” is the long-brewing boss battle with Jay-Z fitted with a beat so grandiose Obama could have ripped it for his Inauguration walkout music, “Tie My Hands” was an oddly sensual rehash of “Georgia Bush,” and “Mrs. Officer” is flirting so forward anyone less hypnotic would catch 6 months in the county.

When the Tha Carter III was released in June of ’08, despite a full leak a week and a half earlier, the record went on to sell 1 million copies in its first week. It was one of only 12 albums to reach the milestone that decade (y’all loved *NSYNC like that huh?) and today is certified 8x’s platinum. Even with all the elevated fan service and critical adulation, there was disappointment that none of the leaks made the record, leaving a “what could have been” taste in the mouth of super fans despite Wayne cresting into global stardom. A more defensible gripe came at the realization that 10 flawless tracks existed on the lengthy LP. Whittling the tracklist down to those 10 it could have made it the 21st century Illmatic meets Thriller meets Pet Sounds, but perfection wasn’t the point.

If he was chasing the status-quo “Lollipop,” a dismembered minimalist 5-minute sexcapade that became the Bing Bang moment for any rapper who ever used auto-tune after, would never have existed. Sure, we’d be better off in a world where “Phone Home” (or “You Ain’t Got Nuthin” or “Pussy Monster” or “Shoot Me Down”) never saw the light of day, but Wayne calling himself a martian alone created a Franz Ferdinand-level butterfly effect that made it worth sitting through a dozen misplaced sound effects and bad hair jokes. Every inflection, bar, auto-tune preset, and beat on the LP would be repurposed over the next 20 years, inspiring thousands of songs to be made in his likeness.

Wayne had laughed in the face of leakers as much as he did the previous 35 years of recorded rap music. What was questionable today would be seen as influential tomorrow, because freedom and confidence always lined his creations’ core. By shredding the fabric of rap, he had solidified himself as a pop culture icon.

The 3 years between Tha Carter III and Carter IV were, even by Lil Wayne standards, messy as hell. On the one hand, he was still an international superstar who lived on the Billboard charts, a GRAMMY winner, and a paparazzi favorite. Yet his half-decade of dominance was running stale. He released a panned “rock” album, became the punchline of early memes, made skateboarding 75% of his personality, recorded an astonishing amount of cunnilingus and constipation bars that never failed to make your ears bleed, and was sent to Rikers Island for 8 months after police discovered a gun on his tour bus in New York City.

Before and after his prison stint Wayne was taking his sweet time to craft Tha Carter IV, and the clock was ticking. Fewer stores were carrying physicals and the growing audience of young people online were fickle, ready to pick and choose songs before buying full albums. Creating oddities for lead singles was becoming tougher as more and more crossover hits had sanitized pop star hooks and formless EDM-inspired production. I Am Not A Human Being and Sorry 4 Tha Wait had already been scoffed off as filler projects.

Simultaneously Wayne had slowly reprised Young Money Records into a conglomerate of G-Leaguers (Jae Millz, Shanell, Lil Chuckie, T-Streets, Short Dawg), homies turned tax right-offs (Gudda Gudda, Mack Maine), guys who peaked as XXL Freshman (Lil Twist, Kidd Kidd), a hot shot hitmaker turned Hollywood heartthrob in that skanky Billy Bob Thorton kinda way (Tyga), and two history altering enigmas (Drake, Nicki Minaj). Add in the building Wayne fatigue with endless new rap stars flooding the internet every week, he found there was no room for error. Nicki and Drake were among those internet darlings becoming stars-in-waiting thanks to Wayne’s seal of approval. One more misstep, and his predecessors would take his spot for good.

Tha Carter IV, released in August of 2011, ended up being a hit. He outsold Watch The Throne, the opulent collision of Hov and Ye, by 600,000 copies in its first week. With a subtle touch, he showed sonically and stylistically that he was tapped in with the rising generation while bodying those deemed his equals.

His verses were presented as poetic hashtag raps about life and lust, even if the punchlines only made his angsty teen skate partners laugh. He turned Rick Ross and Jadakiss into footnotes on their features, Andre 3000 and Busta Rhymes kissed the ring, the intensity of “6 Foot 7 Foot” made “A Milli” look like lay up line, and the stormy beats saw bold stadium status synthwork and pulsing horns akin to the growing wave of Lex Lugerfied trap music. “President Carter” and “Nightmares Of The Bottom” used plucks of harp strings and bouncy piano keys the way a blog darling producer would flip a Joanna Newsome sample.

Bringing back the C1 and C2 formatted interludes and a tighter tracklist showed his ability to acquiesce to a public looking for concision. Add in recurrent battles with a lover’s psyche and a couple of radio bait deluxe tracks, he became realigned with the elite class he was slipping from while remaining in conversation with those shooting up the ranks.

Wayne was no longer an active shaper of culture, but a spry legacy act. Take Care was setting up to wipe all slates clean and the myriad of Pink Friday: Super Mega Roman Grandmaster Deluxe (Target Exclusive Edition) singles were swallowing what little oxygen was left. He gracefully was moving to a different phase of his career, gaining younger fans, killing features and using his years of label cache to keep his singles in drivetime rotation. In many ways it was his death rattle record, one last claw for life as he heel flipped into the sunset.

Rappers never retire, but Wayne’s career was defined by so many firsts it seemed slightly more possible when he announced that Tha Carter V would be his send-off that he meant it. He wanted to tap out at 35, be a dad, skate on pyramids, and do whatever the hell Martians freed from the expectations of pop perfection do. Had everything gone as planned with the albums initial release date in 2014, that may have all come to fruition. Instead, we got the most aggressive battle between a label and its star artist since Prince was writing “slave” on his face.

Main events in Wayne’s multi-year rumble with Cash Money include (but are not limited to): Wayne’s tour bus getting shot up in a semi-connected beef with Young Thug, Tidal getting sued for $50 million over the exclusive release of the Free Weezy Album, a physical altercation with Birdman in Miami, a handful of leaks, a million “coming soon” updates, Wayne accusing UMG of conspiring with Birdman (like father like son fr), and Rick Ross trying to play mediator on “Idols Become Rivals.”

Once the album finally did come in August of 2018, it brought an exhausted sigh of relief more than a moment of celebration. What little hype was left was quickly burnt away after trudging through the over bloated, rudderless tracklist. The most generous read was that it was meant to be his own 4:44; an emotionally vulnerable therapy record but with his patented alien twist applied. “Mess”, “Don’t Cry”, “Can’t Be Broken” and “Let It All Work Out” were bloodletting memory dumps. “Dark Side Of The Moon” and “What About Me” are sing-songy musings on love. Sadly these flashes of focus were washed away by the staggering 23 song tracklist (cut down from the originally promised 31). No meta-narrative was explored, no cultural shift was forced, and only a lone hit (an unlistenable “Special Delivery” redux) could be extracted. For Tha Carter title to be slapped onto it still feels like a sin.

Do the albums Funeral, Trust Fund Babies, Welcome 2 Collegrove or Tha Fix Before Tha VI mean anything to you? For the 99.9% of the population who said “no,” congrats! You still live in a world where seeing Lil Wayne’s name listed as a feature can spark a nostalgic warmth or even enjoyment. For the 0.1% of us who did allow their curiosity to torture them into listening to these albums, it was clear that Wayne was so washed bubbles would fly out of his nose if he sneezed. He had just spent 2024 on a multi-part “woe is me” tour after losing the bid to perform at the Super Bowl LIX halftime show to Kendrick Lamar, and he hadn’t had a song make it back up the charts since appearing on Nicki Minaj’s “RNB” in 2023.

With only 24 hours to go before the album’s July 6 release, “The Days” featuring Bono (yes, lead singer of the most popular band that nobody would ever say is their favorite band) was premiered in a commercial for Game 1 of the NBA Finals. The snippet showed a song that was crafted in a lab to play as bumper music for a low budget CW drama, ready at any moment to be played in a dingy CVS.

A few hours later, an AI promo video copying Jay-Z’s famed Rhapsody commercial began floating around. Right before the first game of the aforementioned Finals, a tracklist surfaced online. We saw features from Andrea Bocelli, Wyclef, Machine Gun Kelly, Jelly Roll, and a few other rappers that should have retired pre-pandemic. Not only were we 0/3 on promo material but Machine Gun Kelly would be involved? What optimism I had left was fully drained from my body.

Tha Carter VI was stacked to the gills with 68 minutes of indescribable garbage. There’s a cover of Wheezer’s “Island In The Sun,” Lin-Manuel Miranda has production credits on a song called “Peanuts 2 N Elephant,” and Mod Sun produced the soulless Kodak Black and Machine Gun Kelly collab, “Alone In The Studio With My Gun.” Then comes all-time groaner lines like “eyes tight like my name Won Ding Ding Dong” or “play pickleball with my dick today.”

Sure, for 25-plus years these ear bleeding lines have floated in Wayne’s catalog, but vintage Wayne sold them with such pizazz you’d talk yourself into believing they were good. Now, his voice appears to be hanging on for dear life, fully ravaged by years of smoking and overuse. Tha Carter VI had moment after moment of Wayne an inch away from coughing on mic. Words slipped away mid-verse falling out of rhythm no matter his best efforts.

I’m thankful Wayne is still kicking, that worrisome images of his dreads falling apart and his face swollen were only temporary ailments, but the world-beating artist has been long dead. With Tha Carter VI, his past lives have been forcibly reanimated into a creature beyond recognition. Playing background singer on his own songs (“Sharks”) and using his own demos for album cuts (“Mula Komin In”) are the kinds of tricks labels pull for a posthumous release. Tha Carter VI has no core goal and no musical throughline. With so little to prove or fight against, somehow Wayne still found a way to leave the world disappointed.

I am convinced every rap fan’s life has been molded by Wayne and his Carter series. His stardom, style, quotables, lighter flick, blizzard of hits, and iconoclastic croak have permeated more lives than any 21st-century pop girly. He’s New Orleans prodigal son, hip-hop’s Stevie Wonder, the living embodiment of rap’s transformation from the voice of the projects to intergalactic sound gardens. Not to mention the father to a multi-generation clan of musical offspring. Whatever slop and let-downs the next 20 years of his career holds are irrelevant, because these last 20-plus have been spent imprinting himself onto the DNA of American music like few before, one Carter at a time.