10 Obscure and Overlooked Blaxploitation Film Soundtracks You Need To Hear

There are many Blaxploitation film soundtracks that have either gone overlooked or followed their namesake title into the shadows of obscurity.

Blaxlpoitation films have a polarizing legacy.

On one hand, the movies that tend to comprise this classification were in a cinematic space in which, for the first time in history, Black representation on screen was designed and portrayed by Black actors and filmmakers. On the other, those stories were often gritty street gospels revolving around criminal elements of impoverished communities. And their characters always had to pick which side of the law they were on instead of, you know, just existing.

A far less controversial aspect of this film era is the music accompanying it. The scores of Blaxploitation films are every bit as star-studded as their marquees on opening night, tapping luminary talents for sophisticated funk suites, sweltering soul symphonies, and cinematic jazz of the highest potency. There are well-worn classics like Marvin Gaye‘s Trouble Man, Curtis Mayfield‘s Superfly, and Willie Hutch‘s The Mack, that are not only sterling studio albums in their own right, but have also shaped the aesthetic and sonic signatures of music decades down the line. Yet the genre is literally brimming with soundtracks that, for a multitude of reasons, have either gone overlooked or simply followed their namesake title into the shadows of obscurity.

As we enter the back half of Black History Month, some of those reels are currently getting dusted off for short revival runs in theaters across the country. Many others won’t be back on screens big or small any time soon (if ever.) So let’s put one up for the Blaxploitation films you need to hear regardless of whether you ever get to actually see them (though most are not terribly hard to find online.)

The Education of Sonny Carson (1974)

Photo Credit: LMPC via Getty Images

Classically trained and well-versed in the soul-anchored pop music of the ’60s and ’70s, Coleridge-Taylor Parkinson was a go-to composer for Blaxploitation films and television shows, as well as some of the era’s biggest acts, including Marvin Gaye, Max Roach, and Harry Belafonte. Those worlds collide in the lush and urgent Leon Ware-assisted soundtrack to the dramatic 1974 adaptation of civil rights activist Sonny Carson’s autobiography.

Solomon King (1974)

Photo Credit: LMPC via Getty Images

Solomon King isn’t the type of movie that develops a following for the right reasons. But even bad movies are occasionally blessed with a music department that cares. Jimmy Lewis‘ propulsive backdrop to this mediocre-at-best 1974 film about a CIA-trained Army-vet-turned-detective hunting down his girlfriend’s murderer (led by a massive 11-minute freakout of an opening theme,) almost redeems the film. Almost.

Melinda (1972)

Photo Credit: John Kisch Archive/Getty Images

Curtis Mayfield isn’t the only former Impressions frontman with an iconic film score to his name. In 1972, Jerry Butler teamed with conductor Jerry Peters for an accompanying composition to a love story gone wrong that would rank amongst Blaxploitation’s most celebrated soundtracks if the movie it propped up was just a few clicks better.

The Baron (1977)

During much of the Blaxploitation era, Gil Scott-Heron and Brian Jackson were a politically-charged bomb of jazz and funk. In 1977, they lent a stunningly sophisticated score to a meta concept about a Black filmmaker being forced to take money from the mob to make the all-Black movie of his dreams. Unfortunately, the soundtrack remains much harder to track down than the film it arrived in. But wise ones know which internet back allies to peer down for a glimpse at this unissued Scott-Heron/Jackson masterpiece. Here’s hoping a proper release isn’t out of the picture.

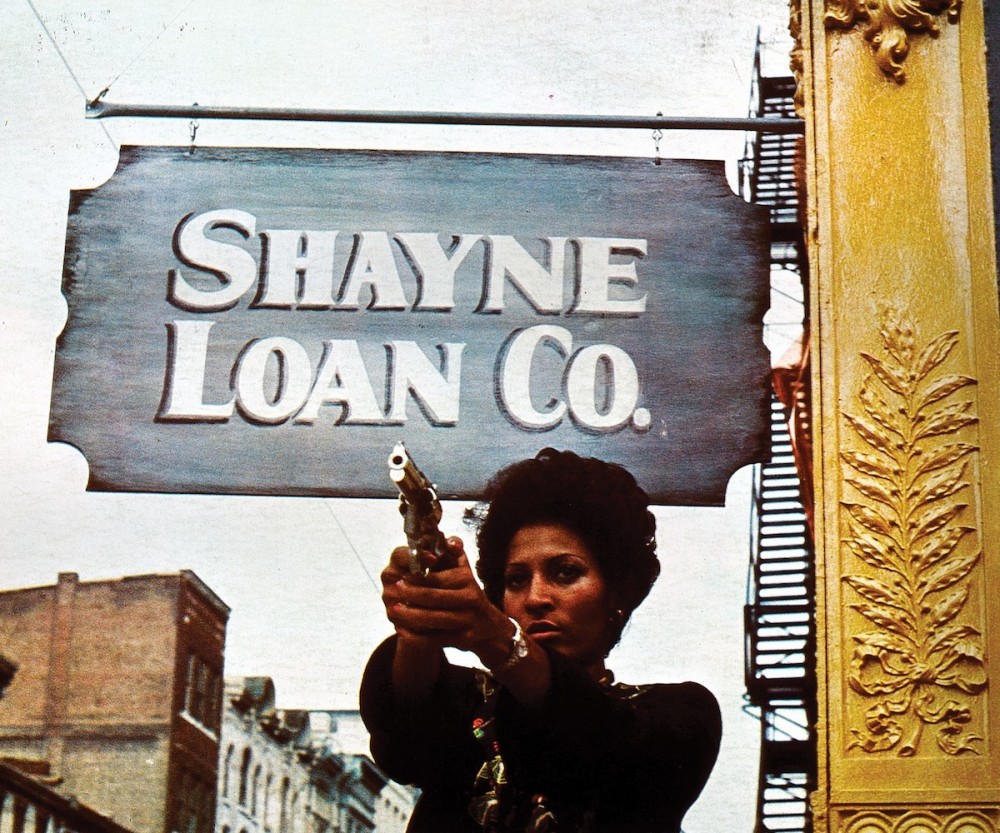

Sheba, Baby (1975)

Photo Credit: John D. Kisch/Separate Cinema Archive/Getty Images

At the peak of her stride in the mid-’70s, Pam Grier was a seemingly ubiquitous presence in Black cinema. But the soundtracks to her films were nearly as beloved as the actress herself. Foxy Brown and Coffy are case in point. But Monk Higgins and Alex Brown’s searingly soulful arrangements for her 1975 film, Sheba, Baby, demand to be a part of the conversation as well.

The Dynamite Brothers (1974)

Photo Credit: LMPC via Getty Images

A venerable jazz organist, Charles Earland wasn’t the obvious choice for an unfunny Rush Hour prototype in 1974. But Earland tapped into his funkiest self to supply the kung fu flick with a high-octane soul-jazz set recorded with some of Prestige’s most notable sessions stars.

For Love of Ivy (1968)

Photo Credit: LMPC via Getty Images

In what might be considered one of the earlier entries into the Blaxploitation genre, Sydney Poitier seduces Abby Lincoln on behalf of a wealthy white family to divert Lincoln from pursuing a better life. Matching the esteem of the cast, Quincy Jones calls on Maya Angelou for words and B.B. King for a few twangy licks on this sprawling and suave-beyond-measure score to the award-winning film.

The Spook Who Sat By The Door (1973)

Photo Credit: LMPC via Getty Images

In the mid-70s, Herbie Hancock was not only reinventing himself, but jazz as a whole. Just as he entered Headhunters mode, the legendary pianist composed a spotless, Rhodes-laced score for a story about a former Fed training gangs and political activists to overthrow a recurring faceless enemy in Blaxploitation, broadly and consistently referred to as The Man. If you’re itching for a raw yet refined preface to Hancock’s air-tight Deathwish soundtrack, look no further.

Black Shampoo (1976)

Photo Credit: LMPC via Getty Images

A flip on a late-’60s comedy about a hairdresser having trouble keeping his relationships untangled, Black Shampoo drops the satire and goes full lover-turned-chainsaw-toting killer in this wild 1976 action film. Gerald Lee miraculously bridges the plot gaps with a suite of explosive funk and spacious ballads that will inspire far more rotations than the film probably deserves.

Lialeh (1974)

It should be pretty clear by now that Blaxploitation films tended to follow into some pretty well-defined sub-genres. There’s, of course, the hustle-heavy street operas, the half-baked odes to Shaw Brothers kung-fu titles, and the occasional romantic romp. That latter motif could itself be split into a few steamier and risqué branches, which is where Lialeh squarely lands. But it shouldn’t be dismissed as softcore anything. Especially not with a starring role and soundtrack from legendary drummer (and inventor of his very own shuffle) Bernard Purdie, whose first and only score is a brilliantly breezy backing to this erotic meta musical.