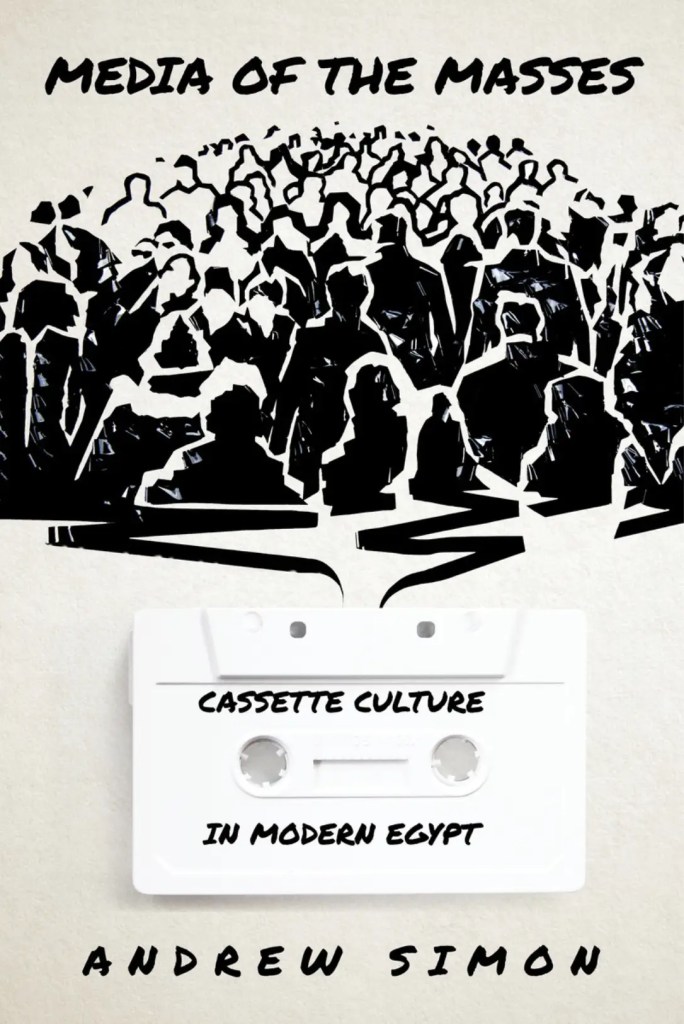

Image via Andrew Simon

Peter Holslin ate all the fuul.

Believe it or not, there was a time and a place where you could make a profit running a DIY cassette label.

That’s one of the revelations I took away from Andrew Simon’s recent book, Media of the Masses: Cassette Culture in Modern Egypt. Published last year by Stanford University Press, this meticulously-researched study takes an academic look at the pop culture scene in Egypt in the 1970s and 1980s—a time when the boom of the oil industry in the Arabian Gulf and a change in Egyptian economic policy known as the infitah (or “opening”) gave way to a rise in consumer culture and a radical reshaping of the country’s musical landscape. Cheap, easily reproducible cassettes proliferated across Egypt by the millions, weakening state controls over music production and ushering in a new guard of populist artists that didn’t adhere to government-sanctioned ideas of culture and taste.

Simon is a historian of Middle Eastern media and pop culture at Dartmouth College, and he spent nearly a decade working on the book. Picking up a book like this, I would have expected a more straightforward history of influential Egyptian labels that mostly put out music on cassette, like SLAM! and Sout El-Hob. That or maybe some glossy scans of plastic cassette shells and colorful J-cards à la the Syrian Cassette Archives.

Simon takes a different approach, though. Relying mostly on media and government sources (including Facebook memes, old news clippings, magazine ads, newspaper comics, and state records), he shows how the humble cassette turned into a lightning rod in a country undergoing major changes. Since tapes could be manufactured and copied with relative ease, practically anybody could become a label owner or pop star overnight—a utopian/dystopian scenario that government authorities and cultural gatekeepers saw as a dire threat to the public order. “According to critics, ordinary citizens, from carpenters to butchers to kiosk owners, had no business making Egyptian culture,” Simon tells me. “For local gatekeepers, the usability of cassette technology was not an asset. It was a liability.”

Even though they were banned from state radio and TV, artists like shaabi pioneer Ahmed Adaweya could build audiences and thrive. The blind, oud-toting songwriter Sheikh Imam managed to grow into an underground legend thanks to the hand-to-hand dissemination of lo-fi live recordings that captured him performing folk songs full of rebellious fervor and archly sardonic anti-government mockery. Egypt today remains under control of a military regime, and the cassette today has lost much of its relevance, both in Egypt and in the United States. Debates over public taste continue to swirl in Egypt, now centered around the festival rap known as mahraganat (which proliferates over YouTube and other streaming channels). Still, Simon argues that tapes like Sheikh Imam’s continue to play an important role, in part by offering a crucial counternarrative to official sources and state-sanctioned discourse, giving curious listeners a glimpse into the people’s point of view.

Recently I got in touch with Simon over email to talk more about the book—read on for our interview. (I’ve made some edits for length and clarity.)