Image via Ethan Higbee

Adam Bhala Lough‘s documentary, The Upsetter: The Life and Music of Lee Scratch Perry, is currently streaming on Criterion and is available for pre-order on Blu-Ray beginning on March 1.

Lee Perry, the enigmatic and innovative reggae producer, became the grandfather figure I never had, imparting wisdom and guidance through his music and personal experiences and giving me the confidence I so dearly needed in order to live the life of an artist.

In 2005, I was living in a studio apartment on 28th street and 3rd avenue on the east side of Manhattan with my soon-to-be wife Joey and our two dogs, Phoebe (an evil and deranged French Bulldog) and Felix (a sweet and timid pit bull). I was 26 years old and unemployed due to the success of my first feature film, Bomb the System. The film, which had garnered an Indie Spirit Award nomination, a small theatrical release across the country, and a premiere on Showtime, was a big enough success to get me an agent at the largest talent agency but not big enough to get me any real work.

I was stuck in a purgatory unique to young, critically acclaimed indie filmmakers. I couldn’t get a real job because I had no experience – other than working at Blockbuster Video and my uncle’s gas station in Virginia. Internship applications at all the major studios and production companies in NYC were all rejected. If I did get an interview, I was told I was over-qualified and should be on set directing features. The execs I met all seemed jealous of my success. But my girlfriend was paying my bills and the entire rent. So I was furiously writing screenplays and taking small directing jobs wherever I could. Jim Jarmusch, a fan of my first film and now a pretty good friend, had thrown me a bone that year by hiring me to shoot some behind-the-scenes footage on his film Broken Flowers, which helped pay the rent for a few months. But the money was running out, and fast.

An answer came from an unlikely source, one of my best friends from NYU, Ethan Higbee, who had previously helped crew on the now-legendary MF DOOM music videos that I had directed while still in film school. Ethan often spoke of a documentary he had been trying to get off the ground for 10 years on reggae and dub legend Lee “Scratch” Perry. I was a fan of Lee’s and even had a couple CDs of his from back in my high school days. I didn’t know much about him other than that he was an eccentric Jamaican who discovered Bob Marley, helped create Dub, and then burned down his own studio because it was “infected by devils.” Ethan said I could co-direct the project with him but only if I could find the financing. I agreed, and set off on a mission to find a pot of gold.

Through the success of Bomb the System, I had met a diverse group of people with money, some of whom were genuine and others were not. One of the genuine ones happened to be a Scratch-fanatic. He owned an Argentinian trucking company with a boyfriend in Buenos Aires, and I tried to convince them to finance the Lee Perry documentary that Ethan had been working on for ten years. They were open to it but with one giant catch: they wanted a life-rights agreement signed by Lee Scratch Perry himself, before any shooting commenced. They wanted to “own” Lee’s life story. Thinking this was never going to happen, I gave up hope then and there.

Image via Ethan Higbee

Ethan approached Lee anyway and asked him to sign over the rights to his story. Shockingly, Lee agreed on one condition: $5,000 in cash delivered in a brown paper bag by the end of the week. In return, he would sign any contract we wanted, on the spot. (I later learned many Jamaicans don’t believe in contracts and will sign the same contract with multiple parties, which is the cause of all the recent lawsuits over the Marley estate). Ethan immediately flew to London with the cash and handed it over to Scratch at a Perry family reunion dinner of sorts with Scratch, three of his ex-wives, and all their children. Our financier now owned the life-rights to Lee Scratch Perry’s story (technically still does). And so my second feature-film and first documentary film was green-lit and a few months into 2005, I found myself on a plane to Zurich, Switzerland, to interview Lee at his ski chalet in a quaint small village 25 miles south of Zurich called Einsiedeln.

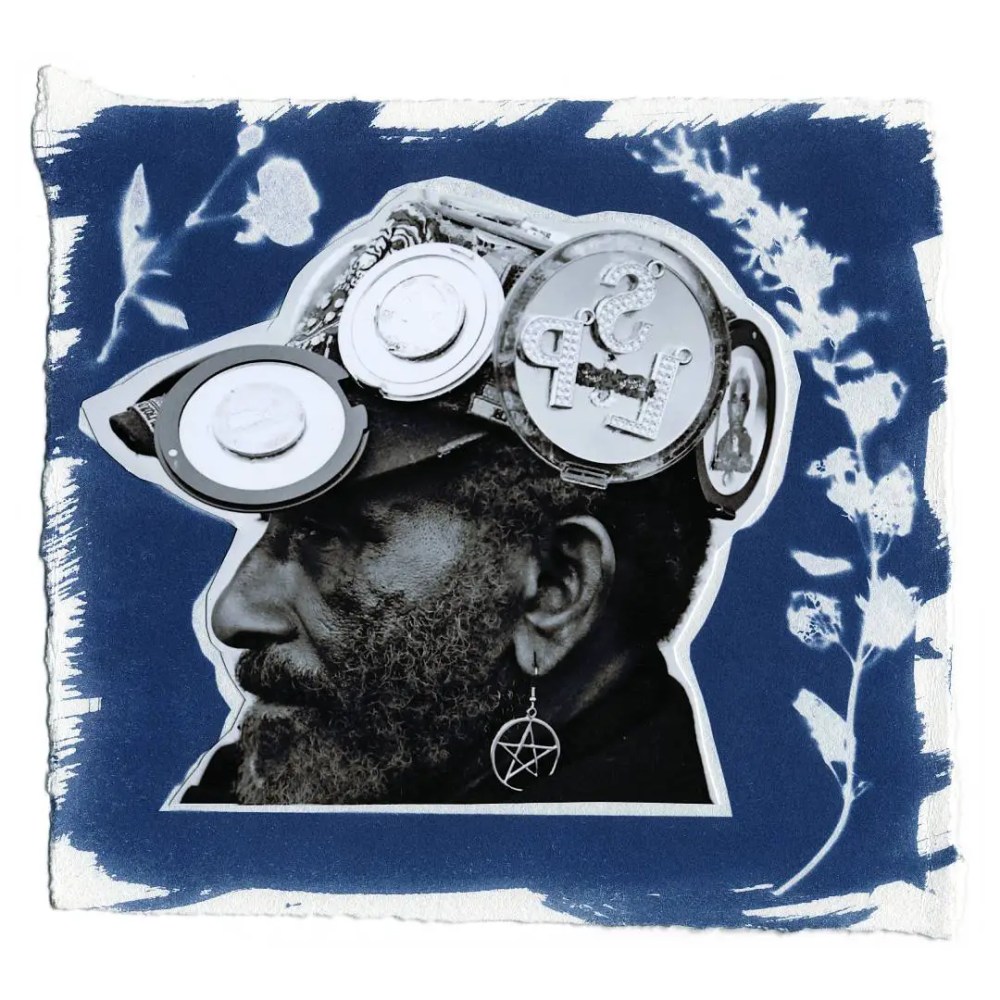

When I met Lee, he was 69 years old, but the first thing I noticed was how he had the energy of a 10-year-old boy hopped up on Mountain Dew. His tiny, sinewy body was constantly moving from spot to spot, almost like a cartoon character teleporting around a room. He would leave his garage studio as we set up the camera equipment, then I would turn around and there he was behind me! He was quite short in stature, but Napoleonic in presence. He dressed as if he had chosen and customized (by hand) every aspect of his outfit individually. Mirrors were glued to his hat and his Timberland boots, patches adhered to his jackets and pants, and even his sunglasses were hand-painted or had trinkets glued to them.

In total, his style was impeccable, no doubt a reflection of his coming of age in Jamaica, where if you stepped out of your house, you absolutely needed to look fresh to death, or don’t even bother. His eyes were piercing and gave you a feeling of danger, a toughness that I would later feel while working on a documentary with Lil Wayne. A hardness acquired from years of dealing with criminals, gangsters, and real murderers. But his smile belied a sweet innocence, and under the ruggedness, an impish child burst forth at the seams. Ethan and I had both heard horror stories of Lee “throwing filmmakers and photographers out on their asses” in fits of rage for doing something as trivial as using the wrong lens or asking the wrong question. We were both scared that was what was in store for us. I was also worried I wouldn’t know how to direct Lee, how to get “gold” out of him, or how to extract a “performance” for the camera – despite the fact that we were shooting a documentary. (After all, every documentary has an element of performance). Laying in our hotel room in Zurich the night before the screening, I did not sleep a wink as I couldn’t stop thinking about all the things that would go wrong the next day.

My worries were all for naught, mainly because one does not direct Lee Perry. One simply turns on the camera and there he goes – as if you’ve bought tickets to a one-man Broadway show, starting right now. During the day, we’d follow the one-man show with cameras in tow as he recited bizarre, often obscene poetry for the camera, poured gasoline on his art and lit it on fire, and walked into a Catholic Church with a giant block of snow on his head to proclaim the Pope dead and the priests all pedophiles. And that was just the first day. At night, we’d set up the lights in his art studio and ask him questions about his past.

We covered every aspect over the course of eight days – from his birth in the small rural town of Hanover in Jamaica, through the Bob Marley years and up to the Beastie Boys and the present day. We filmed him in front of a green screen pretending to drive a car and wave to his fans. I never once saw him drive in real life, but he did tell us the story of when an angry musician cut his breaks on his car in Jamaica and he nearly died. He spoke fondly of Jesus, which I found odd given I thought he was a Rastafarian. Lee loved Jesus and the Bible and would tell us stories of how him and his musicians would sit around the Black Ark thinking up ideas for songs. When they’d run out of ideas they’d open up the Bible, pull out a story or a quote from Jesus, and make a song about it (Bob Marley’s Corner Stone, produced by Lee is one popular example, Daniel Saw the Stone is another).

He’d reveal the origins of some of his most mysterious songs, like the brilliant Cow-Thief Skank: I’ve read some bizarre interpretations of what this mysterious Lee Perry track is about. Lee told us in Switzerland that the meaning is quite simple: it’s a diss-track against fellow record producer Niney the Observer. In his youth Niney had his thumb and finger chopped off by a farmer while trying to steal a cow. So Lee made this track mocking Niney, who he had beef with at the time, and it became a hit. The beat is formed from 3 songs cut-up together – the first time in history that had ever been done before. This was 1973, many years before these techniques would be utilized in hip hop. Finally, late at night we’d eat dinner with Lee, and he loved to talk about gossip – about what Britney Spears was doing or whatever the latest TMZ news was. After the first day, Lee warmed up to us. By the end of the eighth night, we were like his grandkids. We adored him, and the feeling was mutual. But we’d soon learn not to cross Lee Perry or suffer his wrath.

Image via Ethan Higbee

Recently, I have been reading a lot of material by Ram Dass, the American spiritual teacher, psychologist and author. He speaks lovingly of his guru, Maharajji, with whom he spent many years training in India. Dass writes of Maharajji’s ability to perform supernatural acts, such as teleporting and reading minds, which he witnessed personally. In one story, Dass tells of his first meeting with Maharajji shortly after his mother passed away from an enlarged spleen. Maharajji, who spoke little English, asked Dass if his mother had recently died and then whispered the word “spleen” in his ear. As a result of this experience, Dass canceled his plane ticket back to the US and became Maharajii’s student. I would have been skeptical of these claims if I hadn’t experienced similar supernatural powers in Lee Perry. Perry, who liked to call himself “Inspector Gadget,” believed he had the ability to stretch his arms across the planet and move things and people around, causing inexplicable events to occur. I witnessed many magical instances over the course of my three years filming The Upsetter and our 15-year friendship. But one in particular made me never want to cross Lee again.

Soon after finishing our eight-day interview with Lee in Switzerland, we traveled to London to film his show at the Jazz Cafe. While in town, we decided to interview some of the artists that Lee had worked with previously. London was, and still is, home to many Jamaican musician ex-pats. We interviewed Earl 16, Dennis Alcapone, and Carl Bradshaw without incident. But then, at Mad Professor’s interview, something bizarre happened. Lee had a beef with Mad Professor that was still unresolved as of 2005, when we interviewed him. As with most of Lee Perry’s beefs, this one was complicated and hard to parse, so I’ll refrain from discussing it in detail. Just understand that Lee did not want us to interview Professor, and we were going against his wishes by doing so.

However, we were all huge fans of Mad Professor outside of his work with Lee Perry and couldn’t pass up the chance to meet him in person. When we arrived, we found that Professor’s studio was a windowless room with ugly fluorescent lighting that wouldn’t work at all on camera. So, we set up our own lights and Professor took a seat behind his mixing board, ready to start the interview. “Does Lee know you are here?” he asked. “No, actually, he told us not to interview you,” I offered. Professor nodded with a little grin on his face, as if he knew why. Suddenly and inexplicably, all our lights went out. As we sat in the room in the dark, we all chuckled – Inspector Gadget had reached his long arms into the building and turned off all the lights. Our lights didn’t work for the rest of the trip, and we had to settle for interviewing Professor under his ugly fluorescent studio lights, rendering the interview impossible to use. Inspector Gadget had won, and I felt lucky to be left alive. I never crossed Lee Perry again.

As a high-schooler growing up in Virginia I had grand aspirations of one day becoming a filmmaker. I caught the bug when I was 15, working my first part-time job at Blockbuster Video, making $4.25 an hour + unlimited rentals. When I wasn’t stacking VHS tapes I was shooting little short films with my friends on a borrowed Panasonic VHS camcorder. But it wasn’t until my junior year that I started getting real about a career in film and researching film schools. When I got the acceptance letter to NYU film school, I was overjoyed, but much to my consternation, my grandfather wasn’t. He was visiting from India that year and I recall a conversation I had with him in our kitchen when he advised me not to go to film school because there were “no artists in the Bhala family.” A lack of artists in our bloodline meant I couldn’t or shouldn’t become one.

I was used to my grandfather being disappointed in me, I never felt admiration or approval from him in my life- but that was just the way he was and I had long accepted it. He was not a friendly or nurturing man, he was a man who demanded difficult and exacting standards in education, behavior, and all other aspects of a life. But this particular conversation got under my skin. It’s not that I had received a B+ instead of an A on a final- I had gotten accepted to the #1 film school in the world! But he didn’t care one whit, in fact he was upset about it. Never daring to be disrespectful to him, I heard him out and walked away, went back to my room where I cursed him under my breath and cried alone. Sadly, this was the last conversation I ever had with my grandfather. Months later I got a call in my dorm room at NYU from my mom, telling me he had suddenly passed away. I was devastated. He would never get to see me become a successful filmmaker. I would never get to prove him wrong.

Image via Ethan Higbee

When I was a student at NYU, I had no plans to go into the documentary film field. I avoided non-fiction classes and non-fiction assignments. I loved writing screenplays and working with actors, and even took acting classes at NYU. My dream was to make big-budget studio films, and I thought that Bomb the System, my first narrative feature, would be a stepping stone towards achieving that dream. However, The Upsetter turned out to be the stepping stone, and one to a long career in documentaries, rather than narrative, which has now lasted for 18 years. Two years after the release of The Upsetter, I found myself on a tour bus with Lil Wayne, directing what would become the film that launched me into the documentary world: The Carter. I never looked back. If you freeze on the end credits of The Carter, you’ll see a thank you to Lee Scratch Perry. I believe he made that opportunity happen for me.

In many ways, Lee Perry was the grandfather I never had- the mentor who, as he says in the film, “gave me the confidence that it would work,” just as he did with a young Bob Marley and Peter Tosh and many, many musicians and artists up until the end of his life. Scratch made me believe in myself. His guiding hand has been steering me along ever since, even now from heaven where he sits on his Rainbow throne.