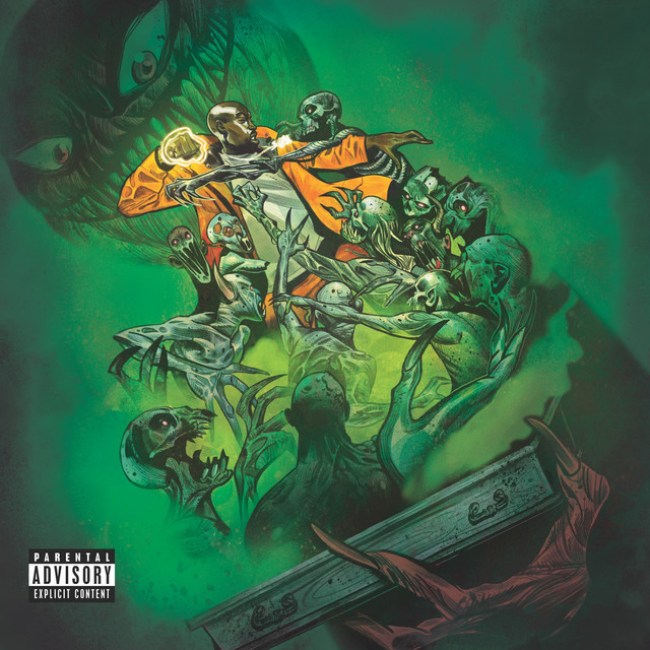

Something About Shirley is the imagined soundtrack for the Book of Revelations, the angel of death unleashing a horde of locusts on the livestream, Sun Ra opening up for Satan at the Bowery Ballroom, a surrealist bricolage of caramelized mummy hands and monsters in the closet, apocalyptic train tracks and pink gunpowder. There is a bible on the dashboard, but the syllables are written in fresh blood.

In just ten minutes, the New Jersey devils, Fatboi Sharif and Roper Williams, tell a story from beginning to end – inhabiting the mind of the heroine as she descends through a disorienting free fall. Sharif plays the witch doctor and occult prophet, whose voice can sound demonic but oddly reassuring. A ticker tape of our worst wears and most deranged fantasies runs in the back of his brain. Sometimes it sounds like he’s being beamed from a space station in Hell. Possessed witches soar in the cursed moonlight. The crib is poisoned. Body bodies slouch across a rainbow. Human sacrifices and firing squad. Then he asks his mother if god still loves him.

Roper operates as an evil sorcerer behind the boards. Chopping up spoken word snippets and unleashing gorgeous piano loops. It’s alternately jazzy, haunted, and doom-laden sound collage. We hear noises that sound like an electronic heartbeat in Gehenna. Voices croaking hello. Fuzz and crashing drums. Fantasia loops and saxophones and old 70s TV show funk. It is the disorienting and mesmerizing sound of postmodern dystopia.

With Something About Shirley, the duo have created something that demands dissection, a polluted but blindingly bright slipstream of vivid images and eerie appeal. Wherever Shirley is, whoever Shirley is, she’s in good hands. – Jeff Weiss

Sixteen years and six hundred lifetimes ago, Sam Shackleton released a tune whose title might as well double as his M.O.: “Death is Not Final.” As Shackleton, he has spent his career exhuming his own approaches, reimagining the familiar again and again until, suddenly, it’s almost unrecognizable. A Shackleton track in 2008 sounds unlike a Shackleton track from 2011 or 2016, and his work is the better for it. The kaleidoscopic nature, after all, is part of the thrill. But the core remains: an interest in searching and out-there electronics runs taut through his discography, whether that’s lights-out dubstep, psychedelic sort-of-folk music, subterranean ambience, or any number of who-knows genre workouts. By this point, by merit of sheer commitment, Shackleton has become a genre of his own.

By looking towards Six Organs of Admittance, a.k.a. Ben Chasny, Shackleton has found one of his most natural sparring partners to date. Jinxed By Being, their full-length collaboration, continues this remarkable tradition, zooming in on a highly particular intersection of sounds. This is ambient music for bad trips, American primitivism left out in the sun, and noise-encrusted folk music, all muttered vocals and stomach-churning drones and screeching amplifier feedback blended together into a dust-storm of an LP. It sounds simultaneously brand-new and ancient; it is a meeting of minds that seems unusual on paper but, in practice, immediately clicks into place. Here, as ever, Shackleton and Six Organs of Admittance continue reaching towards disorientation, building a universe out of forgotten histories, reconfiguring sonic traditions in a game of exquisite corpse. – Michael McKinney

On his second full-length collab with minimalist Montreal beatmaker Nicholas Craven, Detroit’s Boldy James proudly assumes his role as the detailed storyteller. Penalty of Leadership, the first of four albums released by Boldy this year (which has come to be about the standard for him), is a gut-wrenching yet meditative reflection on the fragility of life. Inspired by a traumatic car accident that left him hospitalized and in critical condition in January of 2023, Boldy embarks on a journey that reflects on the past while providing new-found optimism for the future. On “Evil Genius,” he acknowledges that although the subject matter of his music might prevent him from being nominated for Grammys, his storytelling has allowed him to build generational wealth and prove that there is a way out of the Detroit street life.

Boldy’s usual monotonous delivery is on full display throughout Penalty of Leadership. Where this would be the downfall for many emcees, he shines through the struggle –– you can hear the tiredness in his voice, but all this does is allow for his detailed songwriting to take center stage. This time serving as the backbone of his chilling tales, the baritone cadence brings the descriptors to new heights –– “I’m Dizzy Gillepsie in Giuseppe with a bust Presi’” he raps on “Jack Frost,” before declaring that he nicknamed his stepper Black+Decker because all that he knows is drilling. Since his emergence in 2020, Boldy James has been an essential contributor to the Motor City sound, landing somewhere in the middle of Danny Brown’s off-kilter wordplay and the straight-up street musings of guys like Tee Grizzley.

Craven’s sample loops provide vocal tidbits for Boldy to naturally bounce off of – on the intro “Formal Invite,” the sampled refrain of “shots ring out / people shout” is re-imagined as candid life reflections; “how rich am I? / I can still hear the air shocks from the trailer hitch on that semi.” With minimal production behind him, Boldy riddles off one-liners that stick to your gut like oatmeal –– “walk with a limp because my nuts heavy” on “Jack Frost” and “Officer mad ’cause my watch above his pay grade / Ain’t graduate from high school, but my daughter got straight As” on “Straight As.” The future can be bright. – Isaac Fontes

In 2007, Onra released Chinoiseries, a landmark beat project made from records he sourced while traveling in Vietnam. His tasteful flips of previously unheard records, mostly Chinese and Vietnamese pop singles that somehow survived the various conflicts that plagued Vietnam for much of the 20th century, are important sociologically, but they also hit as rugged hip-hop beats. Onra is gifted in finding melodies from the past and combining them with the drums and production techniques of the present. Though he lives and works primarily in Paris, Onra traveled for an extended time in Thailand, restarting the process of scouring record stores, swap meets, and junk stores for 45s. Thailand proved to be a fruitful hunting ground, and he processed a fresh crop of sounds through his MPC to create Nosthaigia, a look back at that trip, that recasts Thai musical history as post-Dilla beat explorations.

The beats on Nosthaigia are at times delicate, sampling the plinking of traditional instruments, and at times strident, taking vocals from lost ballads and melding them into something new. Perhaps the most impressive accomplishment on the new album is Onra’s deft use of the sampler to combine those two modes. On “The Man Who Took The Money,” he flips multiple melodies into a dynamic backing track, but also skillfully manipulates Thai vocals into an approximation of the track’s title spoken in English. It’s a subtle but masterful demonstration of the strengths of an album that would be easy to to overlook or treat as background music, but rewards close listening. – Nate LeBlanc

I’ve always felt like something of a pretender writing about dance music. I have been to a nightclub precisely one time. (Do people call them nightclubs? I am a 38-year-old dad living in rural Indiana.) I left before the act I was there to see — Baauer! Shout out 2012! — because some guy yelled at me for…dancing? I really don’t know.

The members of LA trio Puli are decidedly more connected to the scene than I am. (Low bar.) Phil Cho is a prolific DJ and party-thrower. John Jones makes electronic music that ideally straddles the silky/glitchy line under the moniker AV Moves. Damon Palermo is a long in-demand drummer and producer who’s been putting out music since at least 2008. The three belong to a collective of LA musicians straddling the worlds of jazz and electronic music, represented in the digital world by the dublab internet radio station, and in the real world by venues like Zebulon and Gold Diggers, Leaving Records, and the vinyl bar turned record store In Sheep’s Clothing.

Puli’s debut album Swirling takes all of that unique locality and synthesizes it into a digestible document of a specific time and place. You don’t have to be part of the scene to appreciate dub-inflected Balearic jams like “Ramona” and “Bongo Springs,” nor do you have to be at a hillside party on the east side of LA — or at a nightclub, ha! — to groove along to the sinuous rhythms of “Cloudy” or “Havana Jam.” And that’s the thing: I’ve always loved electronic music despite my distaste for late nights, loud clubs, or, well, anything that involves leaving my house. Albums like Swirling are so great because they don’t require you to be there to feel like you’re a part of something. – Jordan Ryan Pedersen

The laws of music dictate that all years in which a Dave Harrington album arrives, it shall be deemed within the top 50 albums of said year. Further, the annual unimpeachable and indisputable year-end compendium from Passion of the Weiss which rightly features said Harrington release will be penned by the outlet’s leading Harrington devotee, Mr. William Schube. Harrington releases have been promoted across a number of my short lived POW ideas, some of which began as a way to write about the jazz guitarist and former Darkside conjurer. His music brings me such joy, all I want to do is play along. Since I sold my drum set four years ago, the next best thing is to write about it.

Skull Dream occupies a particularly fun part of the Harrington road trip, which since, say, 2016, has featured forays into free jazz epics, soft pop cover albums, dub reimaginings, and electronic landscapes that move from ambient meditations to psychedelic ragas. Harrington does everything all the time, and Skull Dream is just maybe the most precise encapsulation of his grand and sprawling mission. The entire album sounds like Clint Eastwood’s squint, like a tumbleweed slowly shuffling across a movie screen — a wink that the shootout is about to begin. Like any good auteur, though, Harrington knows the satisfaction lies in tension and not resolve, and as such, Skull Dream hints at things that never come, climbing ladders to nowhere in particular with scorched guitars and squawking horns and melted synths and cavernous drums. These sections build and build before taking off their hardhats and heading home. Ready to do it all again tomorrow. – Will Schube

Earlier this year, Sophie Steinberg asked cumgirl8 — the fashion collective-electropunk band-cyberfeminist shitposting YouTube channel who either hail from Manhattan or an 8000-year-old chatroom in another metaverse — how they balance all the words in between the hyphens. “We don’t,” responded drummer Chase Lombardo. “It’s chaotic,” added bassist Lida Fox. Indeed, everything about CG8 — from their music videos to their album art to their onstage ensembles, often made by the band themselves — seems designed to overwhelm, confuse, and, if you’re a misogynist anal wort, infuriate. (The band hands out Plan C pills at their merch table.)

For a band that bites off so much, it’s impressive that the songs on the 8th cumming manage not to lag behind the concept. “Karma Police” — a sublime troll sure to infuriate hordes of Thom Yorkists — sounds like a skanking robot on its last power cell. “uti” is a laugh-out-loud scuzzpunk tribute to the malady that women everywhere wish could just be cured with an OTC med. “hysteria!” is a downtempo soundscape that balances John Carpenter burbles and Moz-indebted crooning — sans white nationalism.

As I was researching this piece, I was trying to explain cumgirl8 to my decidedly not-online wife. “Have you heard of Peaches?” I ventured. She shook her head. A moment later, my two-and-a-half year old daughter exclaimed, “I love Peaches!” Like most parents, I spend an inordinate amount of time wondering who my daughter will be when she grows up, a thought that sometimes raises my blood pressure in the age of “grab ‘em by the pussy” as a presidential slogan. cumgirl8 refuse to kowtow. They respond to the world telling them women can only be one thing by being absolutely everything. CG8 give their listeners a lot to think about. But you know what they give me most of all? Hope. – Jordan Ryan Pedersen

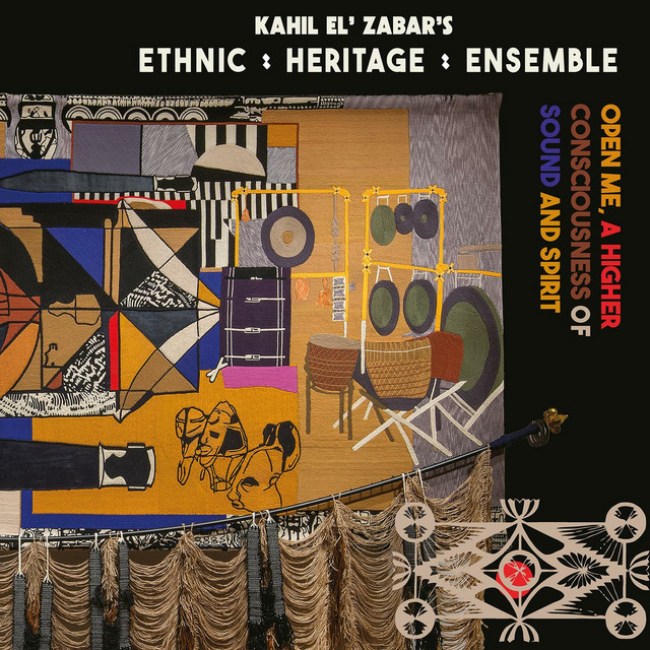

There’s something irresistible about a drummer-lead band. Especially, if said leader is a guiding force as towering as Kahil El’Zabar.

At 73, El’Zabar has seen and influenced many waves of jazz history. He was dubbed the best percussionist in the world by Dizzy Gillespie, helmed the chair of the AACM (Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians) – Chicago’s world-renowned incubator for jazz innovation – and now enjoys another renaissance as a champion of the spiritual and healing modes of improvised music. It doesn’t hurt that he’s usually the wisest, most sharply dressed person in every room he enters.

Ethnic Heritage Ensemble was founded half a century ago on the premise of combining African grooves and collaboration styles with the Creative Jazz trajectory. In its current form, EHE consists of trumpet (the great Corey Wilkes), cello, baritone saxophone, and viola/violin. True to its title, Open Me, A Higher Consciousness of Sound and Spirit, is an album concerned with the spiritual jazz tradition and the greats who have paved the way. “Passion dance” evokes the fire music of Archie Shepp, with immediate bursts of energy on each instrument. “Ornette” honors the great liberator of jazz with a minimalist rhythmic foundation and plenty of space for solos. And with their cover of Gene McDaniel’s protest classic “Compared to What” – a real highlight due to the sound of El’Zabar’s trusted Kalimba and coolly recited lyrics – remind us that righteous anger never goes out of style. Particularly, if nothing ever seems to change.

Apart from its bluesy grooves and El’Zabar’s charismatic vocals, this album is first and foremost the work of a real ensemble. Every part and every player gets its space to shine, as the compositions move steadfastly, stoically, like a freight train, better yet, a brightly-lit cargo ship through icy water at night. – Julian Brimmers

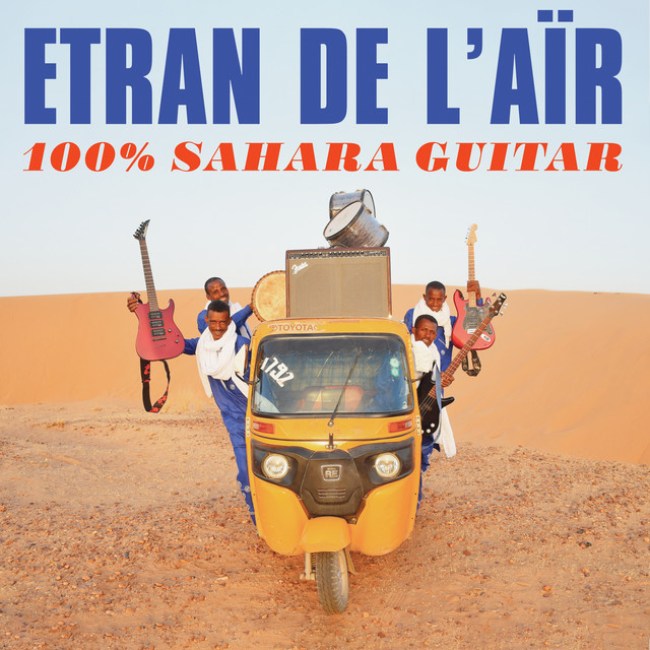

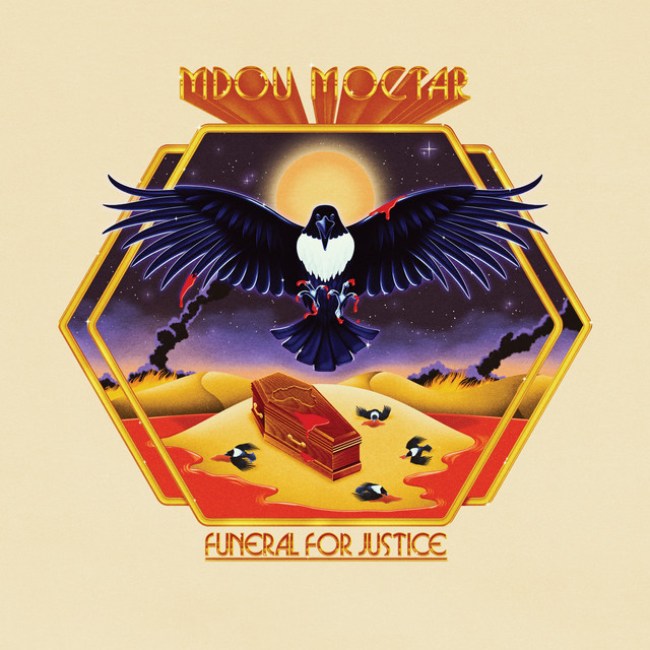

From the livest wedding band in Agadez, Niger to one of the most thrilling live groups in the world today, the brothers of Etran de L’Air (three by blood, one by choice) have come a long way. After applying a DIY ethic to their singular version of Tuareg guitar music—2022’s Agadez was recorded in the titular trade city with a mobile studio; 2018’s No. 1 was captured live with a single microphone—Etran’s international renown took them to studios in Los Angeles and Portland for their third album.

Aside from flirting with Western rock rhythms for the song intros, 100% Sahara Guitar continues the thread laid out on their previous two full-lengths, their EP (which was recorded on WhatsApp), and the dozens of songs they wrote prior to having any recorded material. The guitars weave in and out of each other over the galloping rhythm section (heavy on traditional rhythms from Mali and elsewhere in the Saharan region), brothers Abindi and Allamine raise their voices toward heaven, and if the near telepathic sync of their extended jams doesn’t make you get up and shake your ass, I’d recommend getting someone to check your pulse. – Douglas Martin

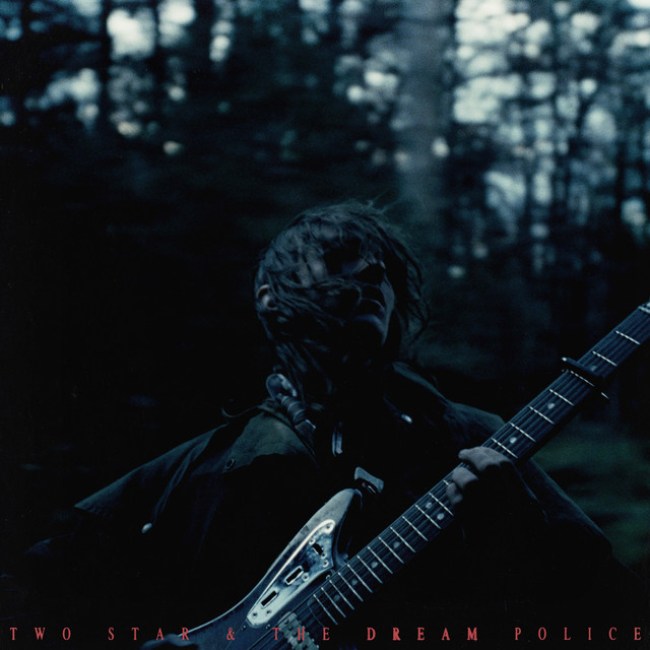

No Name, the sixth solo album from former White Stripes frontman Jack White, finds the Detroit rocker returning to the form that propelled the duo to international fame at the turn of the century. Their raw and urgent garage rock sound emerged from southwest Detroit at the same time as their prep school counterparts The Strokes were taking Manhattan with their decidedly more studied approach. As Michiganders we were admittedly biased, but the Stripes always sounded like the real thing to us, while the Strokes felt more like art school poseurs. Both were still vastly preferable to the torrent of millennial indie nonsense of the 2000s.

So is Jack White the last Rock Star? No Name certainly allows him an opportunity to stake his claim on the cusp of his 50th birthday, having been nominated for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame for the first time last year. The distortion is loud, the drums are thumping, and White has not lost his talent for writing catchy songs or unleashing a plaintive howl over a deceptively insouciant guitar riff. Highlights of the album include the opener “Old Scratch Blues” and “That’s How I’m Feeling.” White delivers an album in the old school sense, meant to be played front to back with no obviously skippable tracks. No Name consistently delivers what White Stripes fans have been missing, though perhaps it lacks the transcendent moments of the duo’s early albums, often supplied by Meg. (The closest track is probably “What’s The Rumpus?”) While No Name might not be a masterpiece in the vein of White Blood Cells, it’s great rock music and a lot of fun, both of which were in short supply in 2024. – Gautham Nagesh

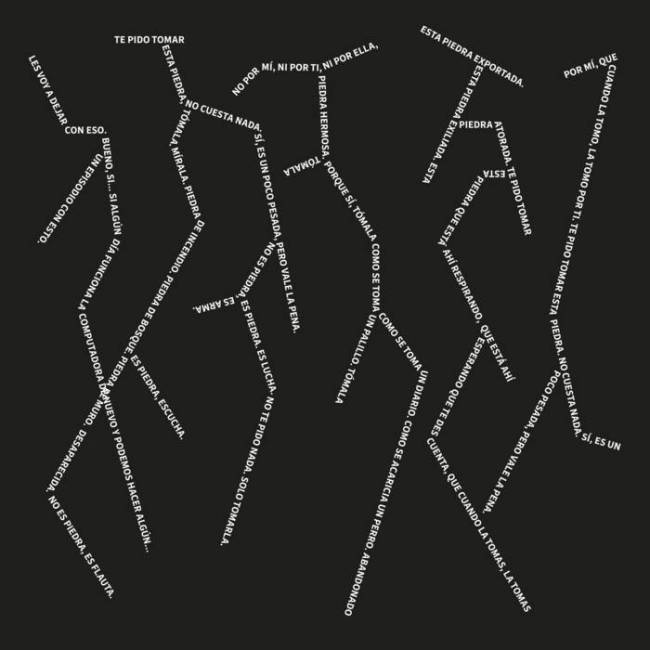

It’s always been about dissolving borders, hasn’t it? When he was barely old enough to drink, Nicolás Jaar released Space Is Only Noise, an LP that was audacious and understated, as unpinnable as it was particular: it was found-sound psychedelia, or bleary-eyed sort-of-jazz, or 4-a.m. kind-of-house-music, or neo-noir disorientation. Jaar has never again made anything that sounds quite like it, but that focus—on filling crevasses between supposedly disparate ideas—has remained. That, in retrospect, seems to be his M.O.; it is the idea binding his pre-LP bootlegs and post-Pinochet collagery; his why-not Daft Punk reimaginings and his interest in zonked-out Soviet cinema; his nearly-silent microhouse experiments and his outright Dadaist DJ sets.

Archivos de Radio Piedras, Jaar’s latest LP, continues that tradition. Like all of his work, it is an unending stretch towards the unfamiliar. It is equally concerned with contemporary headlines as it is with speculative futures; it is a radio play about the present and a time capsule from pre-dictatorial countries the world over. It is remarkable, disorienting, and confrontational, a grab-bag of Jaar at his most wild-eyed and his most subdued. The format, an approach that might seem strange at first, is key: a thick blanket of radio static and a dial that won’t sit still allows Jaar space to conjure a kind of dream logic, building bridges between oral-tradition folk-music histories, fuzzed-out dembow, new-school club sounds, the war in Gaza, and fights for civil rights the world over. In jumbling all these traditions and sounds, he argues that they are all of a piece.

Fundamentally, Archivos de Radio Piedras is about violence, about corpses piling up amidst bombed-out cities, about bodies. Thirteen years after the release of his official debut LP, Jaar is still interested in dissolving borders. This time, though, the stakes are different: it’s no longer about distinctions between genres or traditions. If Jaar has spent his career imagining liminal spaces and shuffling ancient texts into new dictionaries, Archivos de Radio Piedras is the sound of him burning his own library. What good is writing when the books are soaked in blood? – Michael McKinney

Gabe ‘Nandez once told me that, to him, “albums create a universe…I need to write around a world, I need to create a world.” In the context of world-building, a singular producer-emcee pairing certainly seems advantageous, which is maybe why ‘Nandez seems to lean into them so often to create his universes. Following the release of two producer-emcee albums last year (Pangea with Tony Seltzer and H.T. III with Argov, respectively) the New York artist has followed up with another double feature of producer-emcee projects in 2024, expanding the fabric on which each Gabe ‘Nandez universe is etched.

First up is the Wino Willy-assisted Object Permanence, a brief collection of sermons that will have you studying a minimum of four different mythologies to fully grasp the messages ‘Nandez is offering. The EP opens with ‘Nandez evoking the Greek-mythic Golden Fleece and Nat Turner over an eerie jazz sample on “Uchigatana.” Later on the New York emcee gets on his “Galahad and The Grail shit”, embodying the legendarily pure knight of Aurthurian legend as he reads your heart chakra while eating latkes. The rhymes are spit in his signature soot-stained voice, adding Herculean weight to every bar.

False Profit, meanwhile, enlists the services of Thomas Maggart’s soul sampling to distill the titular concept, defined by ‘Nandez as “deceiving tactics employed for personal gain and the sake of intentional misinformation.” On “Commerce God” Maggart warps together piano glissandos and electric guitar as ‘Nandez tells a man “this is planet Earth, sir, everybody’s at war / if you’ve lived long enough you understand me for sure.”

False profits is a pandemic that threatens everyone, though the youth don’t seem to see it. In case the message isn’t clear enough, ‘Nandez doubles down on closer “Lithium,” taking shots at “corny millionaires” manufacturing rap beefs for profit under the guise of authenticity. Maggart rides the beat out for more than half a minute after the last ‘Nandez bar—best use it to consider your false profits. – Kevin Crandall

Still mourning the tragic loss of scene torchbearers Young Slo-Be and Bris, California’s Central Valley has an upstart superstar once again. After first putting the nation on notice in late 2023 with “Apocalypse” and following it up this year with the unlikeliest of TikTok smash hits “Boogieman,” EBK Jaaybo released his breakthrough album The Reaper as he spent his 21st birthday behind bars beginning a three year stint for firearm possession.

The album is a NorCal street rap epic with biblical stakes: choir samples, Satanic motifs, and the earth-shaking super boosted bass that might make you think the sky is parting for the Rapture itself. Jaaybo’s depictions of the realities of the bloody gangland violence of his hometown Stockton – once named by Forbes the “most miserable city in the U.S.,” and the largest U.S. city to ever declare bankruptcy — don’t hold back. Songs like “Straight to Hell” and “Satanic” veer into horrorcore territory.

While Jaaybo’s raps on much of the album are awash with vitriol, the album’s first song “Pops Punch Me In” is an exercise in the type of lilting NorCal vocal sample rap which Jaaybo played a major role in pioneering with his earlier projects. The song offers clues to understanding the man behind the music. Jaaybo’s father Rrari was a local rapper himself who was shot and killed when his son was only 12. Between cut up snippets of phone messages his father left for him, Jaaybo reflects: “And I don’t feel like I’m alive / ‘Cause when Rrari left, I died too.” A piece of your heart breaks with every listen. – Dario McCarty

This is what a “back-to-the-basics” album sounds like, a return to core elements. Wunderkind Nïlufer Yanya’s first album on Ninja Tune was crafted top-to-bottom with long-time collaborator Wilma Archer. Mk.gee may have won the prizefight to define the next half-decade’s guitar presets but there is something equally distinctive about Yanya’s playing across My Method Actor. Her restraint is palpable, especially in comparison to the occasional bombast of her first two studio albums. Guitar notes swirl together like white noise and are picked out like spikes of static; they cosplay a drum padding out a heartbeat (“Made Out of Memory”), or the gentle ebbs of an ocean wave (“Binding”). But the instability at the core of Nilufer’s older music remains present, fireworks lobbed into the air that threaten to sputter back down to earth. “Like I Say (I runaway)” is a song of two halves and a title of two parts, first a wind-up and second a four-seamer ripped down the middle.

As My Method Actor’s title suggests, these songs have the texture of costumes, interchangeable and infinite in their possibility. It’s forever the listener’s conceit that the singer could not just be singing to you but singing for you, gently holding a coat up by its sleeves for you to slide in your arms and try on their life. There is a special intimacy, as if these songs were written just for you, to take out for a walk around the block or live with for a couple decades. Nïlufer may just be acting but it doesn’t feel that way. – Sun-Ui Yum

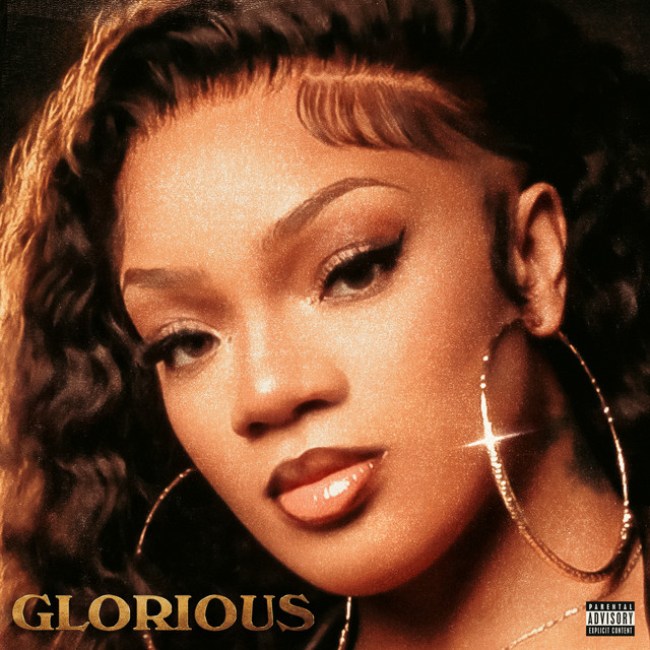

The earth is somehow spinning faster, an internet born calamity that burdens hip-hop artists with “fall off” allegations before they even drop their debut album. Such was the case with Glorilla, the bassy Memphis starlet who broke out with 2022’s Grammy Nominated “F.N.F.” and soon after faced the “what’s next” pressure placed on budding stars. It didn’t take long for fans to pretend that being a woman in rap was a zero-sum proposition, and other ladies’ rises meant that Glo had to swim or sink. While they were speculating, Glo was steadily crafting her moment-meeting debut album Glorious, which cements that she’s here to stay.

As CMG’s cash cow, she unabashedly bid for stardom with a check-every-box approach that mostly works. Alongside prior hit “TGIF,” there’s the syrupy “I Luv Her” with T-Pain, fun linkups with fellow rap divas Latto (“Procedure”), Sexyy Red (“Whatchu Know About Me”), and Megan Thee Stallion (“How I Look”), and the menacing “Step” with Bossman Dlow. But Glorious also shows off her introspective side on the veritable “FNF’ prequel “GLO’S PRAYER,” where she prays for strength to leave a fuckboi. She also gets spiritual on the Kirk Franklin and church organ-featured “Rain Down On Me” which shows off her sense of humor through lines like, “even though he hate me, Lord, watch over my baby father.”

The kitchen sink approach could leave lesser artists with a pile of nothing, but Glo’s dynamic charisma and hypogeal baritone shine throughout the project. More than anything, Glorious demonstrates that she’s not just a rapper with bars, she’s a songwriter who knows how to ideate a concept and execute. She’s not afraid to hit the pulpit, but at her best, Glo succeeds in the lineage of predecessors like La Chat and the late Gangsta Boo, who didn’t reach Glo’s commercial steeple but nonetheless radiated a self-assured, down home charm that’s hard not to love. – Andre Gee

Instrumental trio Total Blue’s debut album fits comfortably on virtual store shelves next to their label’s scintillating reissues, including this year’s Virtual Dreams II – Ambient Explorations In The House & Techno Age, Japan 1993-1999. On the first two tracks, “The Path” and “Corsair,” warped synths and fretless bass lines slither like a Pat Metheny record played at half speed. The delay-heavy pulsing guitar on “Heart of the World” and amorphous ambience of “Dorian Dial” also bring to mind New Age and fusion records from the ‘70s and ‘80s that embraced the grand, chintzy potential of synthesizers and early music programming. In tandem with the album’s cover art by Michael Willis – of a totemic, gasping sculpture seemingly from civilizations ago – the Los Angeles trio evokes the IMAX science documentaries and Eyewitness episodes floating around their own memories.

But Total Blue is far from vaporwave pastiche, and some of its finest moments come when the group jumps to the present day. “Chaparral” glides with sparse keys and cosmic guitars in the first half before dissolving into a beatless downtempo cut on the second. The album’s digital exclusive, “Stone God Stomp”, is their biggest leap into the future, a seven-and-a-half minute slab of dub techno rising from the ground like an alien monolith.The pleasure of Total Blue is in its wide-open terrain, where obtuse experiments, serene soundscapes and primal urges coexist. – Miguel Otárola

It’s hard to discuss the intersection of kung-fu/karate and hip hop without being cliché. Most attempts have a self-impressed tone as if they’re the first to consider the connection. Wu-Tang are the obvious starting point, but the analysis often fizzles out from there and they jump decades ahead to Kendrick Lamar’s “Kung Fu Kenny” persona from DAMN. (They all skip Future “chopping bricks like karate”!) For our purposes, it’s enough to say that talented artists draw from cool shit.

Los Angeles rapper Ralfy the Plug’s latest album Grandmaster Ralfy leans into its kung-fu inspirations with more subtlety than rappers have historically used to signal their affection for the genre. Ralfy’s always been partial to kickboxing, but here he slips into a meditative pocket that contrasts with typical high-energy uses of kung-fu imagery, with no overwrought pentatonic samples or fuzzy dialogue snippets. Grandmaster Ralfy is still aligned with the nervous music pioneered by his brother Drakeo the Ruler, but now Ralfy’s solemnly accepting the anxiety instead of being enamored by its novelty.

The album is, at turns, funny—he needs Bengay to soothe the strain of all the jewelry on his neck—and melancholic as he reflects on lost friends and family. In the aftermath of the tragedies that have plagued the Stinc Team for the last five years, it’s nice to hear Ralfy’s commitment to honing his craft is undiminished. As he says on “No Big Homies”, he got Gold-certified “from Rosemead to Alhambra,” and the only thing that would make it sweeter is if the crew that he built it with were around to polish the plaques. – Miguelito

Night Reign sounds simple and intuitive even though it’s actually layered with linguistic and musical complexity. Following up on the grief-stricken jazz-folk of 2021’s Vulture Prince, Brooklyn-based Pakistani singer/composer Arooj Aftab’s latest consists of gorgeous ballads in which lush arrangements and reverberating quietnesses create space for nocturnal meditation.

Aftab’s music is steeped in Pakistani and American musical traditions. Ripples of spiritual jazz and fusion leave their mark—the ghost of Alice Coltrane blinks through in Maeve Gilchrist’s gentle harp harmonics on “Na Gul,” while “Autumn Leaves” culminates in a brilliant electric organ solo from James Francies that manages to feel both virtuosic and understated. On two tracks, Aftab draws on the exquisite Urdu verse of 18th century poet Mah Laqa Bai Chanda, the first woman to publish a diwan (poetry anthology) of her work. On “Whiskey,” Aftab’s singing style is stirring and precise, bringing a hypnotic sense of longing to a mantra-like paean about a whiskey-drinking lover.

Vijay Iyer, Moor Mother, Kaki King, and other regular collaborators bring texture and intensity to Night Reign, and the utterly hip sophistication of it all certainly helped the album and lead single “Raat Ki Rani” clinch nominations for the upcoming Grammy Awards. But there is nothing showy or high-minded about this album. It is just an enchanting piece of work, fit for close listening, small parties, noirish cocktail bars, lonely rides home, and any other times when the extraordinary and ordinary align. – Peter Holslin

I won’t bore you with the details of why Portishead is one of the greatest bands of the early ‘90s; their skittering trip-hop needs little introduction. I won’t try to nail down the precise word for singer Beth Gibbons’ clear distaste for the spotlight. I certainly won’t compare her decades-long break between creative bursts in the public eye to a magician’s disappearing act party trick.

Beth Gibbons is not elusive—she is aware. On her debut solo album Lives Outgrown, Gibbons has been sanded raw by the passage of time. The album is akin to clear-eyed birdsong on a frigid and stark morning. A permanent blue hour, reflection incarnate. Lives Outgrown mashes folk sensibilities with a desire to play and explore. The resulting soundscapes work up a thick lather. Soft finger picks and woodwinds make up the bulk of the instrumentation, but the music itself is not as fragile as the light guitar strums suggest. Much of the album is backed by hearty drum patterns, a clear iteration on the way Gibbons’ past music used percussion to speed up the heart rate of a song. The feeling peaks on “Beyond The Sun,” which opens with the album’s most cutting question: “If I had known where I’d begun / Would I still fear where I might end?” The space for answers to bloom overtop each other makes the otherwise comforting tunes on this album lofty and dense.

Lives Outgrown is the byproduct of living while others do not get the chance, of untimely farewells and “anxieties and sleepless nighttime ruminations,” as Gibbons wrote in a letter posted to Facebook in February. It slots into the pantheon of precious albums made by artists in their 50s, with their wizened perspective battling against the sobering reality that no one has ever known anything at all. – Donna-Claire

Astrid Sonne looks pretty relaxed on that album cover, all things considering. The Danish singer-songwriter sets the stakes incredibly high on Great Doubt, crafting a baroque pop album about parenthood, unrequited love, anxiety and the uncertainty of our species. There is an undeniable humanity to Sonne’s lyrics, sung sweetly and plainly, and in her steadfastness when faced with a large, mean, catastrophic society. “Do you want to bring people into this world?” she asks in the album opener “Do you wanna,” searching for answers as the drums tick like a time bomb. There might not be much of a choice when you’re in love, a feeling that Sonne lays out with maturity and ambivalence reflective of young couples all over the world.

Like recent albums from collaborators Slauson Malone and ML Buch (the latter remixed Sonne this year), Great Doubt’s production fulfills its thematic inspirations. Sonne depicts both dread and courage with wonderfully analog sonics. Pan flute synths stab through the bass organ on instrumental “Boost.” Enya-esque oboe notes and resplendent harp plucks speckle across “Give my all” and “Almost.” These sounds complement Sonne’s vocals and viola and create an uncanny atmosphere that dissipates like mist at the end of the album’s 26 minutes. One wishes there was a stronger ending to Great Doubt, but given the album’s themes, not offering any closure might be part of the point. – Miguel Otárola

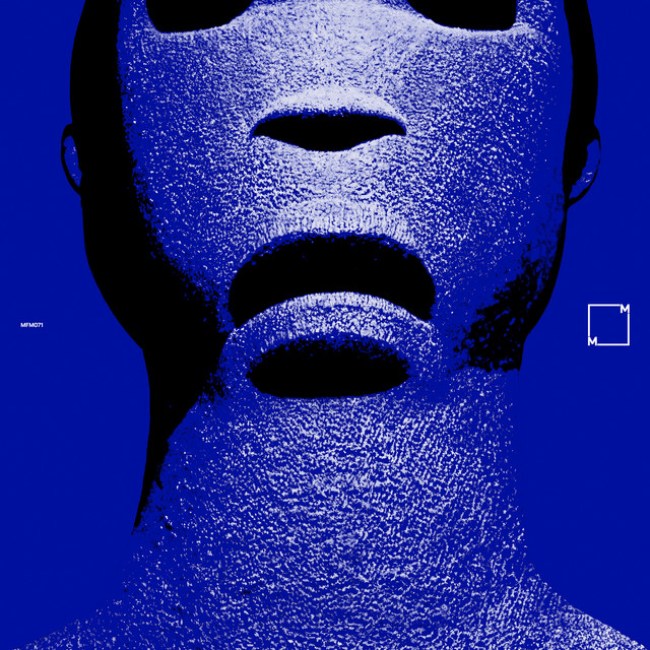

On the cover of REVELATOR, E L U C I D faces the camera like a stand-off. His eyes, hidden behind cat-eye sunglasses, could be making direct eye contact, or looking up towards the heavens, or shut in calm meditation. The effect is striking; if you own a physical copy, you have to pull the record from inside his head to hear it. Given the distortion-fried sounds on the album, such a cover could be seen as “confrontational” or “unsparing” — adjectives that accurately describe REVELATOR, but also feel a little too surface-level to stick. It’s an intense listen, to be sure, a jarring 180 from the dreamy, faded photography palette of 2022’s I Told Bessie. My initial read was that it was an unyielding look at the horrors of it all, a screed against the systemic forces of oppression, and I still think that’s partially true. There’s a real indictment of society in tracks like “THE WORLD IS DOG” and “ZIGZAGZIG,” but reducing the complexity of REVELATOR to mere anger erases the currents of hope flowing beneath its crackling, charred surface.

He creates a beautiful bouquet for his wife on “IKEBANA,” a song named after the Japanese art of flower arrangement. “SKP” celebrates the profound mind meld one can achieve with a partner through sex, conversation, or simply sharing space. The repeated mantra of “Must find fried fish, it’s Friday” on “Hushpuppies” initially sounds frantic, but it’s a tribute to the tradition his grandparents held of gathering the family for a meal each week. E L U C I D implores us to open our eyes not just to the terror of modern life but to the joy and connection we’re able to achieve. There is much to lament, but it only proves how important the fight truly is. As he rapped on Armand Hammer’s “Slewfoot,” somewhere between pessimist and soothsayer, “We’re bored of the apocalypse.” – Dash Lewis

Much of adulthood is about navigating how weird it is to grow up. Mom and Dad discuss nursing homes while you strap a heating pad to your back after a 30 minute jog. Bills, careers, children? On CHROMAKOPIA, Tyler, The Creator’s eighth studio album and arguably his best, the only thing weirder than his own changing world is that other people are bugging out even more than he is. Tyler sounds bewildered and perplexed over the joyful, celebratory production, which moves from Neptunes-inspired productions (“I Killed You”) to stadium-stirring chants (“St. Chroma”) and collegiate marching band arrangements (Jackson State has already performed “Sticky”). Even when rapping about unplanned pregnancies or the intricacies involving his strained relationship with his father, Tyler sounds more curious than enraged, like he’s Katy Perry exploring the jungle in the video for “Roar” (don’t act like you don’t know what I’m talking about).

At his most intense, T conjures feelings of paranoia and bewilderment, especially on the aptly titled “Noid.” Over a proggy, fuzzy sample of “Nizakupanga Ngozi” by Zamrock band Ngozi Family, Tyler wonders who’s at his window and how much his accountant is skimming off the top. 15 years into his career, Tyler’s entire world has been shaded by the surreality of modern celebrity. The only two choices? Laugh or cry. On Chromakopia, Tyler does both. – Will Schube

Kent Loon didn’t always make music like the kind found on Swamp Water. His first album, Stay Low, had an adolescent listlessness to it, with most of the tracks produced by friend and labelmate Chester Watson. That wandering tone has morphed for the Florida rapper in the seven years since its release. He’s found a clearer groove of themes to mine—worldly sins and earthly riches—instead of hopeful searching. Now Kent Loon’s music revolves around the violence of being human, both internal and external, but it fools you so that you don’t notice it at first.

Swamp Water has the veneer of extolling its tracklist’s subject matter (“Pink 50s”, “House on the Hills”, “Red Soda”) because Kent has mastered the murky, acid trap sound he’s been toying with since 2021’s Bittersweet. There are certainly moments of jubilation—naturally stemming from cars, women and money—they’re just scarcer and have more punch when squished next to the depths. Guns don’t have to be shot or substances taken to feel their impact. It’s the nonchalant way he handles these extravagant elements that makes his music relatable even if it shouldn’t be. You haven’t woken up off a pill in Miami racing Lambos, but that line forces the memory of a night of questionable decisions to the surface. Hearing him list narcotics feels like they’re damaging your own body and compels the mind to ruminate on unhealthy habits. Swamp Water has a sturdy roster of features (Father, Valee, Lil Scumbag, Wizz Havinn, Chester Watson, etc.) and Kent’s musings, the joys and lamentations, still take center stage. It’s the lavish package he’s able to construct around these tenebrous realities that keep you listening over and over. – Miguelito

Previous Industries are paying their respects to Father Time. The newly formed rap group—comprised of LA by way of Chicago artists Open Mike Eagle, STILL RIFT, and Video Dave—invoke the spirit of the past in Service Merchandise, looking to craft a new future from its bones. The album takes its name from the now-defunct retail chain, and most of the song titles hold a similar seance for once beloved stores that have been lost to the ceaseless march of hyper-capitalism. The influence of nostalgia-soaked 90s rap is palpable, from the Native Tongues-esque cadences to the Digital Underground flip that propels “Showbiz” to kick off the album. Video Dave feels the rain in his joints and Open Mike realizes that he’s the same age as Bill & Ted. STILL RIFT recalls the times dialing on the rotary phone to order out of the Service Merchandise catalog. It’s a comprehensive homage to the past, propelled by rappers who have been rhyming together from the beginning.

As long time friends and collaborators (Open Mike and STILL RIFF met in high school, Open Mike and Video Dave in undergrad), Service Merchandise is also a chance for the trio to show off the kind of chemistry it takes a lifetime to accomplish. The three pass the mic like prime Steph, Klay and Dray, each feeding off the others while holding their own. Nowhere is this clearer than “White Hen,” where the trio trades four-bar blows over a lush piano refrain. As Open Mike Eagle told our own Will Schube: “Is three a posse? Who knows? [But] the posse cut energy…is all over.” – Kevin Crandall

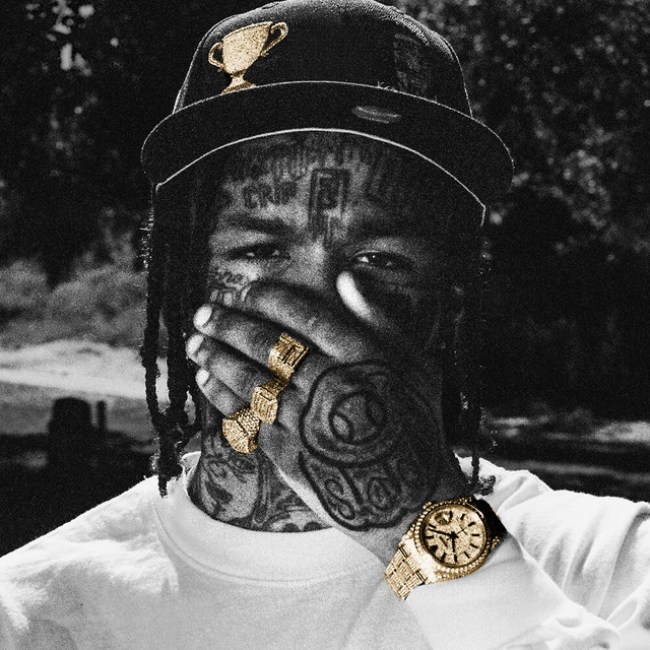

In a year of explicit diss songs, it’s easy to forget that some of the best taunts are loose, cryptic, and impossible to avoid C-Walking to. X4’s second album, Trophied Up, lethargically encapsulates the spirit of South LA’s Rollin 40s, once again immortalizing Drakeo the Ruler’s Cold Devil classic, “Hood Trophy.”

The Stinc Team affiliate’s strain of nervous music creates flare by leaning into his id. Trophied Up is what happens when you brush the angel off your right shoulder and let your devilish conscience take the wheel. X4 raps like a wicked menace, talking shit while unconcerned with the consequences his words may reap. You don’t even need to have beef with X4. If you go as far to even try to look at him funny, he will roast you to embers.

Two of the album’s standouts, “Won’t Last” and “R U Dumb,” transform sparse marimba melodies into masterclasses on nonchalance and subtle braggadocio. With the support of Ralfy the Plug, DaBoii, ASM Bopster, 1TakeJay, and Bravo the Bagchaser, Trophied Up features a showcase of some of the brightest talent in Los Angeles (aka the heavy-hitters that Kendrick shopped for The Pop Out and GNX). Through blasé mumbles, chuckle-worthy grumbles, and the buzz of four syncopated eighth-note bass hits at a time, X4 seethes his way into becoming one of LA’s most unimpressed, impressive orators. – Yousef Srour

One of the first voices you hear on BigXThaPlug’s Take Care is his grandmother telling him how proud she is of his accomplishments. Family is everything to BigX. After dedicating his first album, Amar, to his son, Take Care shifts its focus to the realities of the music industry and the pressures of success, part therapy session, part life update, filled with recognizable samples from Willie Hutch, The Isley Brothers, and Rick James. Barely in his mid-20s, BigX has shown maturity as a young provider who stays in the present. The Big Stepper is flexing these days, but he’s also embracing his mental health by telling people about the dark side of fame. Narrative-driven songs like “Law & Order” and “Story of X” have you invested in his come-up, his Southern drawl glues the listener to every word. His single, “The Largest,” has a dance that’s become a thing on TikTok, and the song gets played everywhere in Dallas.

When I interviewed BigX in October, I wondered if it was time for him to take a break after dropping two projects this year. “As much as I want to, I feel like this is where the exciting stuff happens,” he told me. “For the past three years, we have just been working. I have yet to go overseas or anything. We have just been in the States, grinding. In every city we hit, we did a show. Features, bumped shoulders. All the footwork we had to do, we’ve done it. Now, we those kids on the block that got the private jet.” Take Care is a watermark proving that effort is continuing to pay dividends. – Eric Diep

Seven years after marking a new chapter with You Only Live 2wice, following his acquittal on sexual abuse charges, Freddie Gibbs now contemplates closure on You Only Die 1nce. The Gary, Indiana native is determined to exit on his own terms, not erased by artificial intelligence (“Steel Doors”) or spilling secrets on Vlad TV (“Cosmo Freestyle”). And unlike J. Cole, he won’t delete his candid, often-over-the-top posts on social media (“Rabbit Island”). At 42, with cult classics like Piñata (2014) and Alfredo (2020) cementing his place in hip-hop, Gibbs is increasingly focused on acting, a career pivot he nods to throughout the album. But it’s taken nothing from his deep, commanding voice, still brimming with hunger. Against a lush, soul-and-R&B-inflected backdrop largely crafted by Pops, his rapid-fire delivery remains electrifying.

Much of the album frames Gibbs in conversation with the Devil, who tempts him with the vices of his past: the hustle, the streets, and chaotic relationships (“Ruthless”). Moments of raw self-awareness cut through: “Hurtin’ on the inside and hidin’ behind this tough shit and this misogyny / See, the man in the mirror ain’t gon’ lie to me,” he admits on “Cosmo Freestyle.” This constant tension between indulgence and introspection defines the record. By the closer, “On the Set,” Gibbs reflects on the toll of a relentless profession, paying tribute to fallen peers like Nipsey Hussle and Young Dolph while grappling with his own legacy. You Only Die 1nce underscores that legacy is unshakable. – Santiago Cembrano

Ever since the Yorkshire-born Nia Archives first gained attention through her relentless self-promotion on pandemic-era Instagram, from her position at the forefront of the drum-and-bass revival, Nia Archives throws both Maya Angelou and Britpop over clattering breakbeats, flashes the Union Jack on her merch, and makes room on the dancefloor for the disaffected to dance away the sadness.

It’s all over the tracks featured on Silence Is Loud, Nia Archives’ first full-length album after years of hype-building EPs. Teaming up with fellow Yorkshire producer Ethan P. Flynn, Nia expands her lyrical ambitions and her collages of influences while keeping it straight jungle, from the Primal Scream–like sunniness of “Cards on the Table” to the discordant blues of “Nightmares.” There’s a sense, throughout, that Nia wanted to take the vibes of ’90s and 2000s alt-pop (think Oasis, Beck, MGMT), throw them into a grinder, and mix the refuse with crushed ketamine. Then her voice—reminiscent of Liv.e’s—would float above the sensory clashes, narrating her loneliness and yours. The growing desperation of “Unfinished Business” reflects this, through start-stop sequences of crescendoing guitar licks and pounding bass kicks, accenting laments like “don’t want to find the good in bye.” So does the exasperation of “Out of Options,” which overlays high-octave piano chords and wistful synth loops over acoustic guitar strums for a backbeat. Nia Archives is still experimenting in real time, scouring all the genres that may fit best with her futuristic throwbacks, and we’re lucky to witness that. – Nitish Pahwa

If you told most people the author of 2013’s widely panned Authentic would be dropping a bonafide contender for 2024’s best rap album 11 years later, few would believe it. Despite his undeniable status as hip-hop royalty, the last two decades saw LL spend more time on a CBS soundstage than in a booth releasing the raucous joints that launched Def Jam into the stratosphere in the ‘80s.

So it was a welcome surprise when LL kicked off The Force with “Spirit of Cyrus.” Calling back to the murderous rampage of slain LAPD officer Chris Dorner is a bold choice for an intro, but the mission statement opener — a boom bap concept song in which he portrays a hooded vigilante out to kill racism — serves as a timely reminder of LL’s exquisite storytelling chops. There’s something in the record for every stripe of longtime LL fan to enjoy, from the shit talker sparring with Eminem on “Murdergram Deux” to the flirty fuckboi on the synth-laden, Saweetie-assisted “Proclivities” as Q-Tip’s typically eclectic production never lets up.

The last decade proved that hip-hop is a country for old men, particularly 2024, a year in which Masta Ace, Rakim, and Common dropped throwback boom-bap odysseys. It was fitting, and somewhat surprising, that Farmers Boulevard’s finest would add his name to this year’s roster of rap elder statesmen, and clear them all. – Oumar Saleh

After exploring more introspective themes of heartbreak and loneliness on their previous album, 2019’s Patience, Mannequin Pussy turns their attention to immediate pleasures of the flesh on I Got Heaven. This is raw, carnal and profoundly horny pop punk. The heartbreak still lingers, but this time, it’s been cast to the periphery. The album says sometimes, the best balm for life’s existential problems is to find someone you can get off with.

Profanity has always been the point, the political statement, for the band that named themselves Mannequin Pussy. Dirtbag feminism meets the Kübler-Ross framework of grief in I Got Heaven’s primary metaphor as lead singer Marisa Dabice is a dog without a leash, holding nothing back. “Not a single motherfucker who has tried to lock me up / Could get the collar round my neck or find one that’s big enough,” she sings slyly, “I’m a waste of a woman, but I taste like success.” It’s a gratifying work that feels like tension release, with screams of catharsis – and of pleasure – crowding out the heartache.

This album is still less intensely ‘punk’ than the band’s previous work, with power-pop ballads and fuzzed-out guitars interwoven with the moments of rage, and it slows to a croon on closer “Split Me Open” as Dabice says the quiet part out loud: For all the tough talk, she, too, still yearns for the romantic ideal. Wouldn’t it be great if to be loved was a come-as-you-are proposition, and that that would be enough? But so long as there can still be women who are ‘too’ profane, women who must submit to the conventions of a lover, then the romantic ideal must be no true ideal at all. I Got Heaven offers, as an alternative, a liberating politics of self-love – and the reassurance that it still helps to go out and get some strange in the meantime. – Kevin Yeung

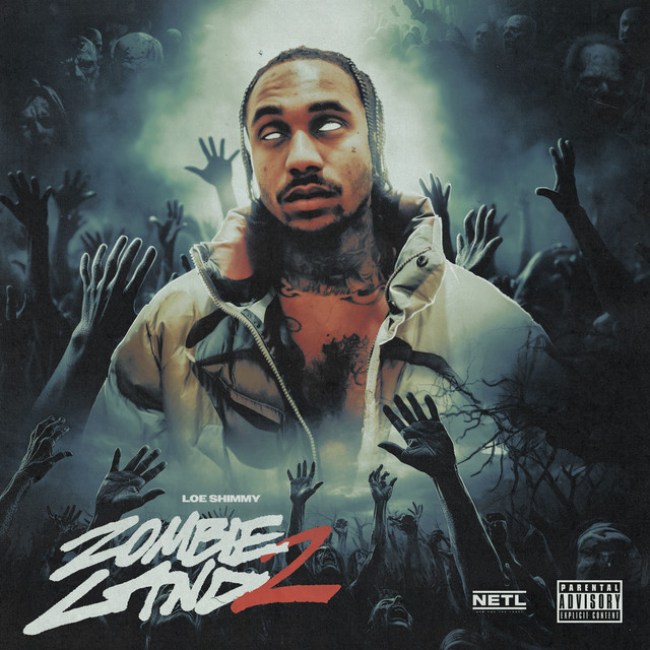

If you haven’t noticed, whole swaths of the country are living in Zombieland. Think LA’s Skid Row, Portland, OR’s downtown area, or the Vlogger-exploited streets of Kensington in Philly, PA. It all looks virtually the same — pictures of tents, garbage, humans unconscious on the sidewalk or nodding off at the waist, held up impressively by two somehow-sturdy legs. There’s no poetry to be found in fentanyl addiction.

Loe Shimmy isn’t concerned so much with these areas. He’s interested in building his own Zombieland, or perhaps breaking out of the Zombieland he’s created for himself, living a life of incessant lean drinking, pill popping and weed smoking, with nary a tolerance break in sight. These addictions become a prison in themselves, but what’s the alternative? Zombieland fucking sucks when you’re sober.

The Floridian rapper has spent the past four years dropping the kind of heart-wrenching street ballads that strike somewhere between Kodak Black and 03 Greedo. He’s a man that seems acutely aware of his emotional limitations, seeking to constantly push past them to dig deeper into his own psyche. The immaculate opening of Zombieland 2, “Pray For Peace,” is a chill-inducing plea for concord, both physical and mental, in the face of constant poverty and violence. It’s one of the most moving moments in music this year, giving way to a mixtape that never lets up in sincerity. “For Me” and “Drugs” are standouts, with the latter showing Loe Shimmy’s potential for true superstardom, but the entire tape has a cohesion rare these days. One that is able to induce in the listener all five stages of grief. – Donny Morrison

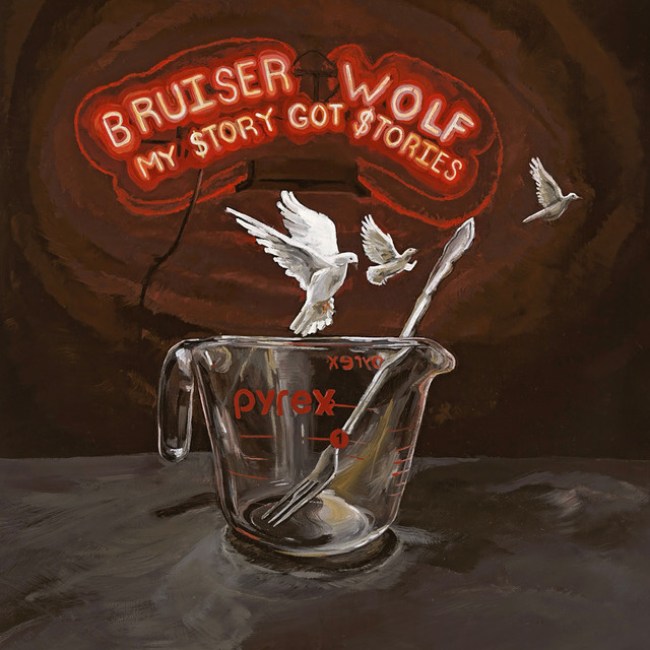

There’s bated-breath suspense when Bruiser Wolf sets up a punchline, the coattailed magician executing a seamless turn. Dinosaurs can’t wait…to try Sarah’s top! You pay for sex…you a buy-sexual! Absurd structures with simplistic reveals pretzeling the English language, they’re all the more thrilling because you should have seen them coming. An eccentric with a nose for detail, Bruiser Wolf makes Magic Eyes, so good on a brushstroke level you can lose sight of his hallucinogenic murals.

My Story Got Stories is a sprawling tragicomedy, its pathos shaded and amplified by humor. Bruiser Wolf is so vivid a narrator he obviates the necessity for a conventional origin story, but the album furnishes one in fragments. There is the latchkey childhood, parents who had no business around children yet provided more than a kid could ask for. The trafficking narratives of “Holla at Ya Mans” and “Hurry Up & Buy” are rendered unglamorous and inevitable, a day job sans benefits. In these contexts, flamboyance isn’t a garnish so much as a lifeline.

It is a slower record than its 2021 predecessor Dope Game Stupid, subsisting on its own hypnotic energy. Guest rappers — Danny Brown, Trinidad James, Chris Crack — wander into the theater and settle into the chorus, brief diversions, never quite at home. Packaging Bruiser Wolf’s multidimensional oral histories is an Olympian task, but My Story Got Stories captures a singular brilliance, if briefly and fleetingly, on record. – Pete Tosiello

Omavi Ammu Minder is one of the finest cubists of his generation. The 25-year-old Carolinian works in monochromatics, forging new shapes from distorted soul samples and narrow rhyme pockets. His latest full-length, shadowbox, is a gray, bleeding-heart confessional. It plays out as a series of imagined arguments and reconciliations with lost souls. It’s intimate without overreach, and its antihero sounds both precocious and exhausted. “open waters” submerges us below a brackish swamp, while “the sky is quiet” becomes an exercise in leaping across rooftops. “latch” is a pen masterclass. He seemingly rhymes entire sentences with each other, and does so without the forced set-ups and strained deliveries attendant to his lesser peers. “Just another poignant mind poisoned by addiction / when I defeat one another three come around grinning,” has been seared into my mind all year.

It’s remarkable how static our protagonist stays throughout this work. While the album evokes so many spirits — from ancestral elders to his inner child trapped in amber — he seldom raises his voice nor concedes any space. If there’s an emotive peak here, it lies within “the giver.” Across distant church keys and chamber choir wails, MAVI sounds like he’s finally reconciling with a wilted relationship. He even admits he tried to strike a few bitter lines from the song, only for those lyrics to somehow emerge from him in predestiny. He says so much, and gives up so very little. – Steven Louis

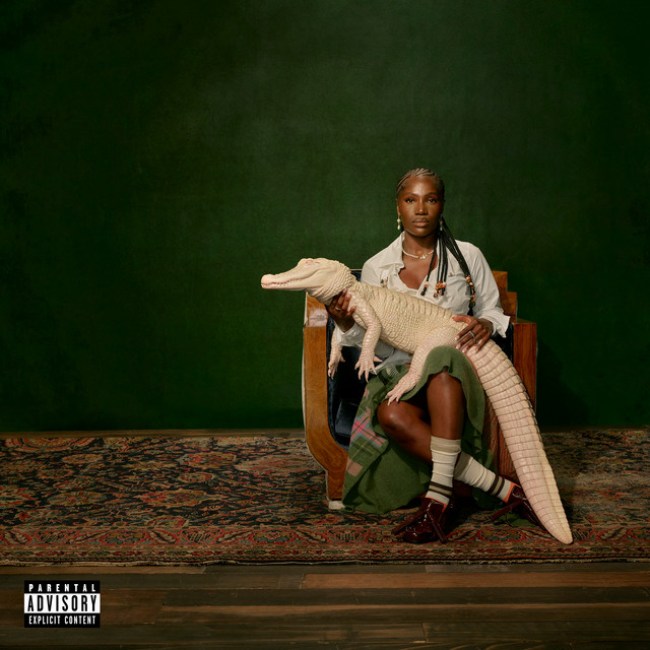

On Doechii’s third mixtape, Alligator Bites Never Heal, the Florida rapper and self-professed Swamp Princess tears apart her personal demons and adversaries. On “Denial is a River,” she spars with her therapist alter ego about a boyfriend who cheated on her with a man and later destroyed her house, the pressures of fame, drowning in her own vices, and a creative numbness that nearly snapped her in half. But she’s uninterested in pity or industry mollycoddling – on “BOILED PEANUTS,” she raps, “Label always up my ass like anal beads. Why can’t all these label n***as just let me be?” Then she proceeds to scat over a euphoric instrumental on “BOOMBAP” where she attacks each norm and shrunken thought that would dilute her idiosyncrasy. She offsets these explosions of vulnerability and pique with tracks like “BLOOM,” a ballad about self-love and “Wait” where she sings a soulful hook to remind the audience (and the suits) of her versatility.

When an alligator sinks its teeth into its prey, it performs a “deathroll” – it twists its body to dismember its prey. This is the maneuver for which Doechii named her mixtape, but don’t the open wounds in her lyrics fool you – she is predator, not prey. She is no easy bitch to swallow and will flip fans and foes upside down. She is everything she wants to be, nothing you can define, and she’s only started testing the waters. – Tracy Kawalik

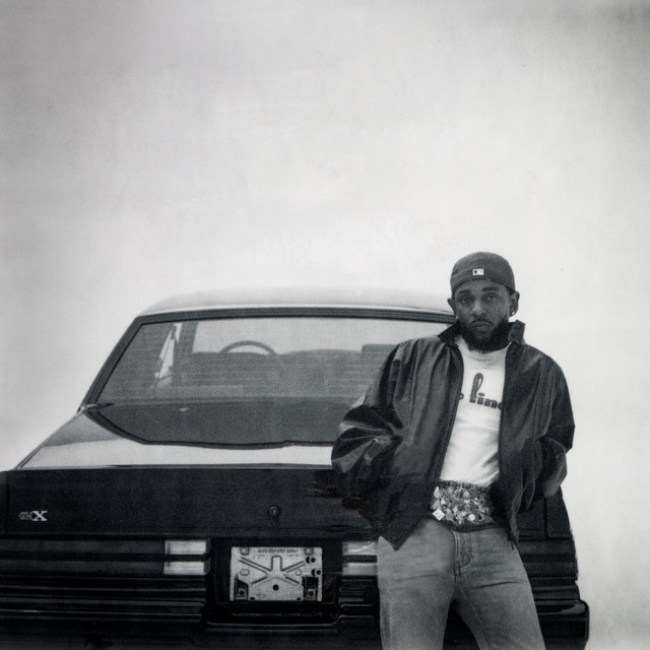

On an unremarkable November afternoon, I was rotting in bed, scrolling through Twitter, when Kendrick Lamar stunned us with GNX, an unannounced drop less than a week before Thanksgiving. 2024 was a great year to be a Kendrick fan. The Pulitzer Prize-winner bounced back, and in many ways realized the potential we’d projected onto him for 15 years. This spring, he declared himself the greatest rapper alive with five rapid-fire disses, each serving as an additional headshot to former collaborator, Toronto superstar, and newly murdered corpse, Drake. It was the most we’ve heard from him since 2022’s Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers. GNX came two months after “Watch the Party Die,” released as an untitled track on September 11th, where Kendrick voiced his long-time grievances with the music industry, the work of an artist who clearly had more to get off his chest post-beef.

GNX is a departure from Mr. Morale, returning, perhaps even re-inventing himself as the mainstream-conversant rapper making a Song of the Summer/Year/Decade gave him a taste for. After piñata-bashing Drake as a regional swagger Columbus, Kendrick cloaked himself in performative LA homerism with this summer’s “Pop Out” concert/national event, continued on GNX, where he shared the mic with burgeoning regional talent (Dody 6 on bass-heavy “hey now” and AzChike on “peekaboo”) and experimented with flows popularized by the late Drakeo the Ruler. Throughout the album, Kendrick exemplifies his lyrical prowess; his GOAT status is confirmed with punchy, quotable lyrics. “Have you ever took a fade and ran three more back to back?” Kendrick probes on the soulful “dodger blue,” before rhyming, “Oh you haven’t? Then shut the fuck up and keep it rap”, a crude reminder to his peers to keep it cute and never come for his crown again.

“squabble up” is another swing at a “conventional” hit that immerses listeners in a groove steeped in the tradition of G-Funk, while “tv off” takes a trip upstate to dabble in hyphy. GNX is a collaboration behind the boards, a marriage between producers with contrasting backgrounds as diverse as Sounwave and, uh, Jack Antonoff, declaring a new beginning for Lamar, on a new label (pgLang). The album leaves us wondering, what comes next, and can we get much higher? – Deb Ashley

There’s something to be said for album title as mission statement.

In Colour, Jamie XX’s acclaimed 2015 solo debut, signaled a synesthetic dissolve from the xx’s shadowy sonic hues to a dazzling soundscape of retro rave, dancehall, and alt-pop—all filtered through a prism of nostalgia and melancholy. Nine long years later, we have In Waves, a kinetic title that instantly conveys motion, crescendo, and inevitable surrender to the pulsating rhythms of the dance floor.

The album lives up to that billing with an inspired celebration of dance culture delivered with an archival sensibility. The opening track, “Wanna,” kicks off with a Wilhelm scream-like airhorn blast that nods to pirate radio broadcasts. Then the plaintive chorus from Tina Moore’s “Never Let You Go” bubbles over an orchestral arrangement and a warbling sample from Double99’s classic “RIPGroove.”

If you recognize these easter eggs, congratulations. But this album doesn’t break stride to pat you on the back. After “Wanna” comes 2024’s most inspired run of bangers: “Treat Each Other Right” marries garage with chipmunk soul, “Waited All Night” reunites the xx gang for a house revival, and “Baddy On The Floor” is a Honey Dijon collaboration that somehow synthesizes every great Basement Jaxx song. The psychedelic “Dafodil” gives you a chance to catch your breath, but the album’s not even halfway through and the best tracks are still to come.

Throughout, Jamie sashays between styles, weaving disparate samples into cohesive musical ideas. Fittingly, The Avalanches themselves turn up on “All You Children” to help flip a spoken word poem for adolescents into a tribal paean to clubbing.

There’ve been complaints in some corners of the internet that these pastiches represent a sanitized simulacrum of real club culture™. Ignore that posturing. In Waves is a front-to-back classic that rivals (and maybe even surpasses) In Colour. – Pete Hunt

The irony of this year’s green-hued Brat Summer is that it fostered the very overanalysis that Charli XCX was hoping to sidestep—the hyperfocus on the “metaphor” of Brat over the resonance of its blunt nature. “Brat,” as Charli XCX explained in TikToks and interviews, was as simple as the lo-fi text-square album cover that typified its aesthetic: to be yourself, your most unapologetic, indulging that instant gratification, those vices and vanities. But to ask what brat meant, or to “aspire” to its status à la Jake Tapper, was to miss the point. To realize it was born of an artist considered generation-defining by some and little-known by others, a Scottish-Indian raver from outer London uncomfortably adjusted to coastal club routines, a cultural historian who endorses nostalgia for its rot instead of its false comforts, was to understand why Brat is the diary for the “role model of a very flawed, genuinely real, non-perfect person,” as Charli describes herself—and why so many appreciated that frankness.

There’s something apt about how Brat finally propelled Charli XCX to the wide fame that’s long evaded her—that, in the best album of her long career, she perfected the balance between devil-may-care radio pop (“I Love It”), vintage dance music/It Girl tributes (“1999”), jittery hyperpop (Pop 2), and grungy Tumblr angst (“You (Ha Ha Ha)”) that informed the development of her sound. All while writing, in her words, “quick and fast and dirty” songs to match, their titles and choruses tailormade for Instagram captions. Here, Charli is fully herself: thirsty, indecisive, problematic, haughty, melancholy. As danceable and forward-thinking as ever. Behold the club staple “B2b,” so repetitive and ambivalent that you never want it to end; the indie sleaze anthem “Spring Breakers,” whose stomp-clap production hosts a cocktail of party rapping, Vroom Vroom callbacks, and Britney references that evokes those endless strobe lights; the spiteful, hard-charging insolence of “Von Dutch,” which finds vengeance and catharsis in distorted drum machines and taunting echoes of “I’m your number one, your number one … ”

This is Charli’s open reckoning, an amalgam of her vast interests and talents with lyrics specific enough—about A.G. Cook, Lorde, the late Sophie—to invite messy speculation over her social life but general enough to welcome listeners’ identification with her boldest exclamations (“I’d say that there was a God if they could stop this”). Guess what? She knows your secret. Put your hands up. – Nitish Pahwa

You can’t fully grok Skrilla (no Elon) without first understanding Kensington, the Philly neighborhood from which he hails. It’s home to one of the largest open-air drug markets in the world, and its attendant blight and poverty is the result of deindustrialization followed by failures by local government on almost every level — whether it’s policing, harm reduction, housing, infrastructure, community development, public health, or, more recently, managing the creep of gentrification. When it comes to Kensington, Philly’s fucked it up. City Hall ignores the neighborhood until it becomes politically expedient: our current mayor, Cherelle Parker, ran on “cleaning Kensington up,” whatever that means, and this spring used pro-Gaza protests at local universities as cover to send cops into the neighborhood in the dead of night to clear out the unhoused people, many of whom are drug users, who live there. That these folks all came back is unimportant to Parker and her administration, as is the fact that the neighborhood’s conditions remain in homeostasis.

Enter Skrilla, who over the past few years has managed to emerge from the scrum of the Philly street rap scene, far too often defined by tragically petty beef (and, in the case of OT7 Quanny, occasional dalliances with Trump), and ascend to an unlikely spot on the national stage. In addition to being a wildly charismatic guy who’s cool with just about everyone in the city, Skrilla is an active participant in both sides of Kensington’s drug market. His hyper-nihilistic raps split the difference between the city’s signature off-kilter flow and Gucci at his spaciest, and the totality of the hermetic world he creates — ominous, paranoid, and kinetic, topped with a dollop of Santeria — forces even high-profile guests such as Lil Baby to conform to it. More than anything, the record is a reminder of the inherent humanity of Kensington’s residents, a reminder to a world that would rather forget them that they’re still here.- Drew Millard

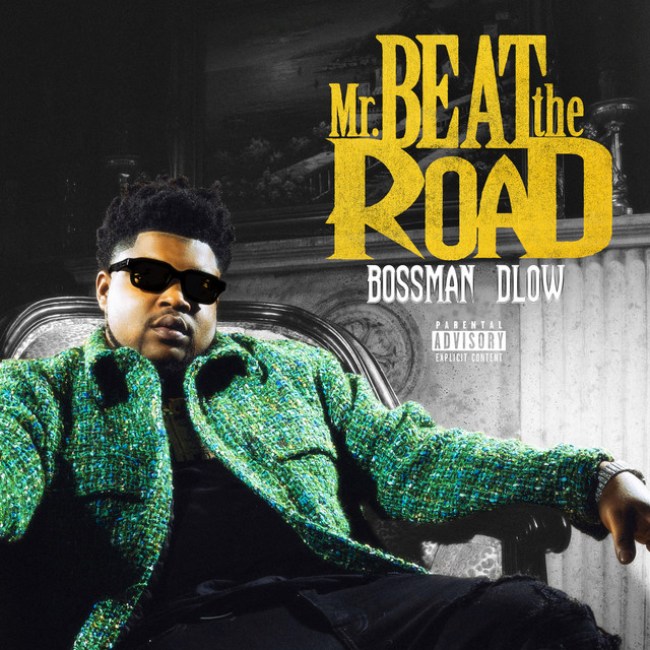

Self-perception is finicky business. According to Bossman Dlow, his particular brand of offhanded street rap doesn’t require much thought. In an interview he gave a few weeks back to The Breakfast Club, he responded to Charlemagne’s question about requests for Bossman to switch up his flow and be “more lyrical like Kendrick Lamar.” Setting aside the laziness of sourcing interview questions from ambient internet opinions, the Port Salerno, Florida rapper replied, “Man, I ain’t finna do all that thinkin…we tryna to turn up.” I respect how he swats away the question, even if we should dismiss the premise. There’s the obvious equating of technical skill with the number of composition notebooks used while creating an album — if you’re going to grumble about punch-ins, this isn’t the place for you — but it also neglects the ways in which Bossman Dlow’s flow and content has progressed since his initial tapes in 2023. The seeds of humor and ingenuity were present in “2 Slippery” and they come to fruition on “Mr. Beat The Road.”

Bossman Dlow makes music that’s appropriate for late night 80+ mph excursions or training for the NFL combine. He slurs words the way only a Floridian can and combines it with precise sports references similar to the type Sada Baby would make in his 2018-19 run. Whether he’s inventing novel pronunciations of Julius Randle’s name or saying ‘baby’ like Al Pacino in Heat, it’s always a thrilling listen no matter what antiquated talking heads say. I’d argue that does require a lot of thinking, it’s just difficult to call it that yourself when it comes so naturally. – Miguelito

Endlessness, the sophomore album by Belgian ambient-jazz savant Nala Sinephro, is like a novel with a perfect first sentence.

Out of one small arpeggio, a whole universe of sound spools out, expanding, tightening up, switching in shape and texture as the tracks (“Continuum 1 – 10”) progress.

Throughout the journey, the listener gets to latch onto all kinds of complex emotions – or bask in pure bliss, depending on one’s focus and which musical motif one chooses to follow. Creating such a spectrum is in itself an amazing achievement.

Sinephro may have started out in her hometown of Brussels, learning to play the harp after brushes with many other instruments, but she found her musical family as a music college dropout in London. The deep connections to kindred spirits like saxophone player Nubya Garcia, and the sense of togetherness she found still informs her work. On Endlessness, she is joined by a crack squad of LDN jazz staples including Garcia, drummers Morgan Simpson (Ex-Black Midi) and Natcyet Wakili, tenor saxophonist James Mollison from Ezra Collective, and pianist Lyle Barton.

As with Sinephro’s debut, Space 1.8, many critics have chosen to highlight the soothing, therapeutic and spaced-out moments of Endlessness, often referencing her personal history with health struggles. Undoubtedly, those elements are there (skip right to the sublime beginning of “Continuum 4” for a taste). But anyone lucky enough to have seen Sinephro and her conspirators perform this music live, knows that it’s just as much about the overpowering and chaotic moments. The disorientation between the synth lines and hectic drum fills, and the tension between the swelling of strings, brass and electronics that sometimes dissolves into light, sometimes into darkness. In that, Endlessness feels less precious than its predecessor, but more intense, more urgent. More like lived experience, perhaps. – Julian Brimmers

On the first two verses of “Custard Spoon,” Cavalier’s flow is orderly and competent with a consistent rhythm between bars and emphasis where you’d expect. On his third verse, he lobs a grenade – some bars are overflowing with syllables and others have gaping spaces; at the same time, he lapses in and out of a dizzying internal rhyme scheme (“Your whole team need a v-steam / I roll my own then throw a bone to the Pekingese.”). On the fourth verse, he comes back to Earth. Even when rappers are capable of such feats, they often hold back for fear of overwhelming the casual listener. Not Cavalier, whose flow has the elasticity and acrobatics of a fourteen year old Chinese gymnast – or if you prefer, Andre 3000.

In 2024, Cavalier returned from a six-year hiatus to release Cine and Different Type Time. Circling 40, Cavalier reflects on what brought him to this present moment. He revisits friends and family with whom he cut his teeth and a city that imparted its traditions. On the latter, Cavalier speaks in a dialect only intelligible to New Yorkers of a certain age: pebble beaches, the Lo cookout, Fulton Street Israelites. In the hands of lesser artists, introspection quickly becomes solipsistic navel-gazing, but Cavalier retains his swagger as he turns inward (“Peeling a satsuma while I still clap culo”).

If there is an epiphany in these two albums, he has hidden it well – he writes in labyrinthine euphemisms that would confound Earl Sweatshirt. Rather, Cavalier ruminates on his life thus far with skills that rival rap’s very best – and he spares the listener the pretensions of such an exercise. In his words, “It’s not highfalutin, it’s upper echelon.” – Evan Nabavian

By 2023, MJ Lenderman, the proud son of Asheville, North Carolina, was quickly garnering buzz as a young name in indie rock as a guitarist in the band Wednesday. His debut album, Boat Songs EP, became a pillar of the unofficial “dudes rock” movement with his enveloping guitar tones, shaky voice that always teetered on the verge of cracking, and self-deprecating lyrics reflective of Gen Z loneliness and heartbreak, like if Neil Young grew up on Drive By Truckers in the 2000s and drank beer on unkempt Appalachian patios.

The buzz hit a fever pitch this summer with the release of Manning Fireworks. While not his first full-length release, it felt like a fully realized vision of MJ Lenderman. It broke out to a bigger audience for several reasons: the perfect storm of social media hum, excellent late night show performances, and bountiful critical praise. The music itself felt more narrative-driven than the fractured images of his earlier work; lead single “She’s Leaving You” is a thinly-veiled lamentation of the dissipation of his relationship with Wednesday lead singer Karly Hartzmann, and “On My Knees” is a more vulnerable confessional from a man seemingly on the brink.

The sound on Manning Fireworks is more multidimensional as well. In addition to his guitar tones straight from the soul of America, tracks like “You Don’t Know the Shape I’m In” see Lenderman moving slow and tender, channeling his inner Wilco with mosaics of arguing outside McDonalds and feeling romantic distance at a waterpark. Lenderman has transcended his “Dudes Rock” and into the realm of truly profound American rock music. – Jameson Draper

By now, especially among underground rap fans, the mystery and ambiguity underpinning Mach-Hommy’s artistry is well understood. He raps in academic tangents about mental slavery (“The true lethal weapon is in the mind / It ain’t the guns, it is what you thinking” Mach rapped on “Fresh off the Boat”) and social inequality, hiding his face behind silk masks adorned with Haitian war symbolism and giving us few clues on his exact origin story. We know he was born in Port-du-Prince, Haiti and moved to Newark, New Jersey as a small child, classing both communities as chaotic war-zones.

Despite all these hardships, he’s elevated to a prominent figure within America’s contemporary underground rap scene. Back in 2017, Mach-Hommy released so many great records (nine to be exact) in one year it honestly felt like he must be on the emcee equivalent of steroids. He has a wicked sense of humor, too, rapping on one career best Griselda-backed block anthem about shooting you in the mouth so that you can spit out your magnum opus. Yet there’s also some glaring contradictions at play.

Mach has an overwhelmingly empathetic socialist perspective in his raps, where even compassion is shown for pimps who walk around with a limp (see “Russian Dolls”)… but he also sells vinyl and concert tickets at hyper-inflated prices. The latter mechanic alienates a lot of his working-class fans and perhaps furthers elitist “limited drop” tactics more prominent in the fashion world. While you could make a compelling argument Mach is simply turning verbose street rap into high art and playing trust fund yuppies at their own problematic game, there’s also an inner conflict going on that rap Discord channels tend to overlook. Can someone who sells vinyl for in excess of $500 also be the voice of the working classes?

With all its psychedelic boom-bap beats that seem to be shot through with mescaline, Mach uses the 2024 album #RICHAXXHAITIAN to transition from criticizing “trologdyte” IDF officials bombing Gaza (“Politickle”) to slick wordplay that condemns liberals for having a vegan mindset to beef. He shares touching revelations about being kept alive by Amoxicillin back in Haiti (“Sur Le Pont’D’avignon”) and even complains on a skit to Haitian Jack (yeah, the one 2Pac hated) about “avaricious” politicians bleeding poor countries out of their resources. But he also routinely breaks off into dazzling yet slightly gibberish pieces of alliteration about smoking blunts with Darth Vader, reveling in calling his enemies “meat balls” and taking eccentric swing after eccentric swing like Dali throwing haymakers. RICHAXXHAITIAN perhaps offers the clearest sonic growth in its 03 Greedo-featuring and Kaytranada-produced title track. Tonally, it feels like the artists’ various conflicting sides are all trying to square one up one another, which is both exhilarating and unpredictable to listen to.

This is a project where the artist says so much, without revealing that much at all, and it’s this deftness of touch that makes Mach-Hommy feel so different for hip hop in the over-sharing theatrics of this TikTok era. On #RICHAXXHAITIAN it’s like Mach can’t decide whether he’s Huey Newton at a political rally or Styles P clowning a foolish underling in a bodega, but this tug of war approach captures the glorious essence of what it is to be a walking contradiction in America.

#RICHAXXHAITIAN’s schizophrenic layering also fits so well with an always online world where we all maintain so many different identities. Just like Mach precisely croons on “GUGGENHEIM JUICE”, a shimmering highlight here, “There’s more than one way to skin a cat.” It’s a phrase he repeats again and again like a mantra, and it seems reflective of the reality that to be a successful Black man in a post-colonial world, you really have no choice other than to be, well, complicated. If you can solve all its riddles, #RICHAXXHAITIAN might just be the most well-rounded portrayal yet of the complicated individual that sits behind the Mach-Hommy persona. – Thomas Hobbs

To the uninitiated, the rapid-fire flows and surrealist diatribes of Phiik and Lungs would be lazily derided as the kind of verbose rappity-rap that’s often used to describe the likes of Logic and post-Relapse Eminem. While it takes a few listens to truly unravel what NYC’s newly anointed underground sages are on about, the beauty of Carrot Season is that behind their Ritalin raps lies a bevy of creative put-downs and zany-but-it-kinda-makes-sense non sequiturs (“Eric Adams in Versace telling me the city’s improving / Plug’s kid a psycho mess, left unchecked would be the next Putin”).

The comparisons between the Long Islanders and Def Jux alumni such as Cannibal Ox and El-P’s Company Flow are understandably plentiful, but phiik and Lungs’ devil-may-care attitude on constructing a coherent narrative stands out from the pack. A first-time listen of Carrot Season is likely to stoke visions of the pair unearthing their copy of Funcrusher Plus, inspiring them to volley verses at each other under clouds of smoke emanating from the blunt(s) of Runtz they’re rotating.

Lungs’ choice to concede production duties to Houston-based Olasegun also marks a sonic departure from their Another Planet quadrilogy, with the duo riding roughshod over beats that are best listened to on a hammock during a hazy summer’s day. With a supporting cast (AKAI SOLO, Homeboy Sandman, and POW’s own Fatboi Sharif) that encourages their out-of-the-box oddities, phiik and Lungs’ latest offering is sure to turn more heads their way in the months and years to come. Just don’t expect to catch their barrage of witty lyricism on the first go-round. – Oumar Saleh

100 million streaming metrics or not, it had to sting when We Don’t Trust You, Future’s reunion (read: comeback) album with Metro Boomin, got its roll out hijacked by Kendrick Lamar’s screwfaced gauntlet throwing. But while the so-called Big 3 bickered, it’s Future and Metro’s second drop of the year that justified the hype. We Still Don’t Trust You is Future at his horniest and most melodic, a flurry of toxic texts in rap form set to Brownstone samples and airy synths. It hit particularly hard a decade removed from “the run,” in a year where industry plants like Yeat and ian tried in vain to replicate the magic of peak Atlanta, fooling no one but brain rot-addled suburbanites and mountain-climbing A&Rs with electric guitars. Accept no substitutes: Future continues to be his generation’s most emotional and incisive bluesman and everybody else with a cracked copy of autotune is just living in his shadow, bar Thugger.

Yet somehow those two albums (plus bonus disc) were just Future building steam ahead of Mixtape Pluto. Reuniting with the 808 Mafia members who don’t have the Weeknd on speed dial, the tape is Future at his hungriest, abandoning pop pretense for low budget Trap and the kind of internal logic that only arrives after 48 hours without sleep under the influence of heavy narcotics. Even the bad ideas – a Godfather theme flip in 2024 – somehow work, while the good ideas like Plutoski’s actual, honest to god, mumble rap are the sort of transcendent moments that can only occur when a rapper is truly locked in. Throw in “Lost My Dog,” an aching ballad that will go down as possibly the greatest ode to dead homies since Pac left us, and it’s clear that Future’s southern gothic horror remains unchallenged and undiminished. –Son Raw