Even labors of love come at the significant cost of time. This is the result of hundreds of hours of labor. Three editors and dozens of contributors attempting to capture the spirit of the old weird Internet. Should you value what we do, please consider donating to our Patreon. It is the only way we can continue to survive.

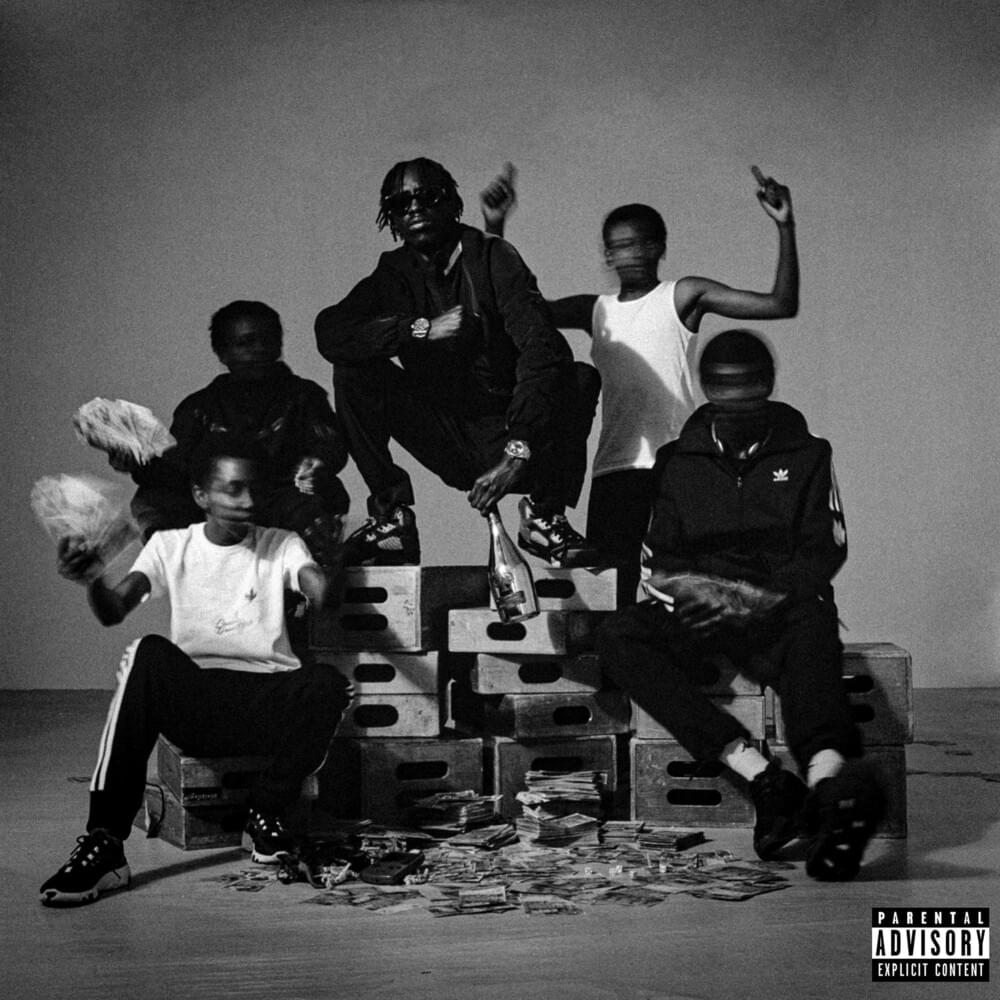

50. EST Gee – Bigger Than Life or Death [CMG / Interscope Records]

Most rappers gloat about the luxurious spoils which come from their street escapades. For Kentucky spitter EST Gee, the grit is the glitter. A brick of Fentanyl doesn’t represent the Rolex Sky-Dweller it’s worth; it represents a brick of Fentanyl.

Bigger Than Life Or Death is Gee’s fifth mixtape but first real breakthrough into mainstream rap. It’s cutthroat and malicious, the result of 27 years of absorbing the ever-evolving trap landscape and running it through a blender. Influences from Chief Keef, Future, Boosie, and Jeezy swirl through Gee’s centrifuge, pulled apart and repackaged into codeine-fueled anthems fueled by demonic percussion and a flurry of sinister keys.

Bigger Than Life Or Death carries no fluff or filler. There’s nothing delicate or subtle about Gee’s delivery; he brutalizes the production (which was masterfully handled in large part by Louisville’s FOREVEROLLING), attacking through pockets when they appear and torching his way into new ones when they don’t. The keys to Gee’s success were present dating back to 2019’s El Toro, but the growth he’s demonstrated in just two years speaks volumes. The maturation on Bigger Than Life Or Death goes beyond a heightened production budget (thanks to a deal with Yo Gotti’s label) and the inclusion of big names from Lil Baby to Young Thug. He found his voice and a way to bring his street tales to the masses without sacrificing the spark which brought him to stardom in the first place. — DAVID BRAKE

49. Bris – Tricky Dance Moves [TrueStory Ent]

“It’s messy, you feel me? This shit bring a lot of drama,” Bris, Sacramento’s preternaturally gifted Tricky-Dancing Emu, told Rap Shack in a video interview shortly before his death in June 2020. While OMB Peezy signed to 300 Entertainment and Mozzy climbed Billboard, Bris positioned himself as an unrefined, material part of the Sacramento soil. He used to shoot dice and kick it with Stephon Clark. He saw his own lyrics used against him in paperwork filed by bloodthirsty local cops. He got his neighborhood set inked above his temples. “I’m so Fruit I’ll put a banana where the clip hang,” he smirked over “RidgeGang,” the intro to his debut album and one of so many shoutouts to his Fruitridge folks.

Born Christopher Treadwell, Bris first teased his singular talent for elastic, chilly, densely-plotted shit-talking on “Panhandling,” which I wrote about with unbound admiration on the 2019 version of this list. Just a few months later, fresh out of jail and blowing up off the strength of “Need Hammy,” the 24-year-old Elk Grove resident was found dead in his car from a gunshot wound on June 21. A father gone on Father’s Day, a hood hero stolen on the corner of Fruitridge and Franklin Blvd. The loss stunned and gutted supporters across the state, and the burden of assuming Bris’ massive career potential went entirely into Tricky Dance Moves, the posthumous debut LP.

It’s a hollowing listen when considering the circumstances, but I’m going to remember and forever live with the album as its creator wanted: snarling to the boundless, icy production and cackling out loud over four punchlines per four bars. “Bitch need permission I can’t let her sneeze / gettin’ to that guap need that cheddar cheese,” he spits on “Did A Bitch Wrong” alongside fellow people’s champion of California Drakeo the Ruler. “Forty jumpin’ out my palm, it’s a handshaker / that bitch forgot about Lil Bris ‘cuz she’s a XanTaker.” Bris’ Tricky Dance Moves is endlessly quotable, musically unnerving and spiritually devastating. He’ll be mourned as one of California’s all-time greats, bar-for-bar and step-for-step. — STEVEN LOUIS

48. Pearl & The Oysters – Flowerland [Feeltrip Records]

Juliette Pearl Davis and Joachim Polack are two French transplants living in Los Angeles after a spell Gainesville, Florida, but they present as the kind of flower children who’d abscond on an acid-laced journey to the candy colored world depicted on the cover of their third album. Truth is, Flowerland is less a savage trip as it is blissful and comforting. Pearl & The Oysters make lounge pop with ripples of 1960s Parisian yé-yé records, Brazilian bossa nova, and Burt Bacharach sophistication. There are electric pianos, light acoustic guitars, neatly plucked basslines, and drum machines that resemble metronomes, all presented with an illuminating analogue warmth. And then there’s Davis’s soft voice, filtering in melodies as gentle as autumn air.

Even when the album reaches a vertex on the drum rolls of “Satellite,” it’s still relaxed enough to keep you in your chair, clutching the record sleeve. Arctic Monkeys tried to make an album of this kind of song a few years ago, but you need a certain warmth in your spirit to make great lounge pop. It’s something that can’t be faked. — DEAN VAN NGUYEN

47. Enumclaw – Jimbo Demo EP [Suite A]

Indie rock’s been soft since sexless, white R&B gentrifiers came through and crushed the buildings. Enter a guitars-and-drums quartet from Lakewood, Washington—a felled Douglas Fir away from Tacoma, affectionately known in some circles as “Grit City.” Fronted by a charismatic ex-DJ known all over the Puget Sound region for throwing guerilla warehouse parties (Aramis Johnson, sporting the most iconic bushy mustache since Mario), Enumclaw play blown-out, major-key pop songs filled with plaintive but sweeping and memorable choruses and narratives filled with off-center insight.

While other indie rockers cheekily retweet memes of the Gallagher brothers bickering, Enumclaw proudly and ambitiously assert they’re the best band since Oasis. Fitting, because like Liam and Noel in their heyday, they’ve got jams.

In the spirit of populist songwriting, the five-song Jimbo Demo EP is all killer, no filler. A tapestry of barefoot Cinderellas, fucking on the lawn, the endless search for self-actualization, the existential resistance against being a loser, mulling over heartbreak and erectile dysfunction on I-5 South. The guitars are as hazy as a Pacific Northwestern autumn morning and the rhythm section keeps time like a dinner plate spinning on a stick. The twin currents of young adulthood, ennui and anxiety, run through these songs like they’re attached to Johnson and guitarist Nathan Cornell’s pedalboards. If Pavement spent less time thumbing their noses at being famous and actually went for it, maybe we wouldn’t need this loosey-goosey band with the lovably off-key singer named after a redneck town. But thank god we do. — MARTIN DOUGLAS

46. Injury Reserve – By the Time I Get to Phoenix [Self-Released]

Each song on Injury Reserve’s By The Time I Get To Phoenix sounds like it could fall apart at any second. Or they are falling apart in real time, as we listen to producer Parker Corey’s intentional dissembling of traditional musical elements. His rearrangement of samples, verses, drums and bass shatters preconceived notions of what a rap song should be, or even what Injury Reserve sounded like before. Delays, glitches, beat-repeating kick drums, twitching hi-hats, and heavy reverb provide a more complex texture than most other albums bother to build. Ritchie with a T’s vocals are pitched-down or doused in autotune or other effects, and his changing voice sounds like a different rapper from track to track. ZelooperZ, perhaps the only one who could handle such impossible beats, is the lone feature.

The group’s live performance approach has been to create spontaneous new instrumentals from clips using Ableton effects and plugins. They transferred that approach into the recording process this time around, reworking the tracks into this final fragmented form. It’s like a new version of the wall of sound: rap music to stand there and be overwhelmed by.

The trio’s sophomore album is their first release following the passing of foundational member Stepa J. Groggs, who died last June at age 32. Although the tone of the album is dark and the lyrics are retroactively foreboding, Groggs was involved in its creation all the way up to its title, which is inspired by Isaac Hayes 18-minute rendition of the endlessly-covered standard. Groggs appears for only two verses, including a powerful meditation about growing old on “Knees,” but his presence weighs heavy on what could be the group’s final recorded offering.

The genesis of By The Time I Get To Phoenix came from a DJ set Injury Reserve performed in the back of an Italian restaurant in Stockholm during a 2019 tour. They played Black Country, New Road’s “Athens, France,” then transitioned into a new song they were working on that sampled that relatively new post-punk tune. Their improvised performance eventually became “Superman That,” the album’s standout track: a genre-defying, transformative achievement. The rest of the songs, which were completed in the grief-addled months after Groggs’ passing, didn’t mesh with their label, Loma Vista Recordings. So they left and put it out independently. It’s a testament to what the group’s late member wanted to make: “some weird shit.” Beauty and wonder and hope and horror melded together in one sonic package that could take lifetimes to unwrap. — WILL HAGLE

45. Blockhead – Space Werewolves Will Be the End of Us [Future Archive Recordings]

Blockhead made his name in the turn-of-the-century underground NYC rap scene by sampling from a wide range of genres—experimental jazz, film scores, classical musicians from India—and adding heavy drums, crafting gripping soundscapes that could sound either eerie or playful. Yet his latest solo release, Space Werewolves Will Be the End of Us All, may have some of the best work of his two-decade-long career. Here, the sample collages are denser and more intricate; vocals taken from stand-up bits and campy sci-fi/horror B-movies are sprinkled across loops from the space-age composer Attilio Mineo, as well as from disco groups like Chic, Kleeer, and Brandye, while syncopated drum beats and music box–like piano and synth riffs keep your ears alert. And there are treats for longtime fans of the beatsmith: Intrepid listeners will recognize, in “For Fork’s sake,” a sample similar to the intro loop used in the late MF DOOM’s “Rhymes Like Dimes,” one of Blockhead’s favorite songs.

Despite the over-the-top album art and title, Space Werewolves is no joyride. The album was inspired by and created during the darkest eras of the pandemic and lockdown, and the apocalypse-lite grandiosity of “Nostalgia Is a Scam” plus the unease of “Werewolves Love Astrology” reflect this. But neither is the album a morose slog; exercises in funky drumming, beat switches, and dynamic arcs like “The Candy Tangerine Man” attest to that. What Space Werewolves demonstrates is both the evolution of Blockhead’s creativity over time, and the imagination and existential worry fueled by a once-in-a-lifetime crisis. This makes for a complex work that warrants repeated listening—to scour all the emotions embedded within, to register the wide variety of rhythms and samples and sounds used, to fully appreciate the range of Blockhead’s craft. — NITISH PAHWA

44. Dawn Richard – Second Line [Merge Records]

You would be forgiven for thinking that an album called Second Line would have a heavy emphasis on traditional brass bands, serving as a celebration of the fallen. This is an album that resists easy comparison points and set traditions. As Richard herself has said (note for editors: it was on an NPR podcast), it’s about celebrating legacy in your own way. There are no rules other than the ones that we are willing to make for ourselves because that’s how music should be.

It’s tempting to read the album as Richard playing her own funeral and reviewers also found it hard to resist the easy comparisons to Solange’s last two albums. However, this is an album that rejects simplistic comparisons. Richard expertly weaves her own musical tapestry, jumping from reggae to Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata in a way that allows the two to feel connected. Everything is refracted through the lens of New Orleans, an audio document of sorts.

While there are songs where she nods to the Second Line traditions in a more overt way (“Bussiframe”), there are also songs that remind you of her pop genius (“Jacuzzi”). It’s fun to fantasize about the straightforward pop music that she could still make but she’s not about to wallow in the past. She knows all too well what happens when the merry go round stops. That’s why she’s created her own universe where she’s not beholden to the trends of the moment. Her mother’s only true love may have been her father, but hers, as she makes painfully clear, is the music. — HAROLD BINGO

43. Cleo Sol – Mother [Forever Living Originals]

On 2021’s beautiful subtle and simply titled Mother, British soul artist Cleo Sol reveals her own new title and the newborn with which it was born. With her baby resting on her chest and a framed photo of her own mother hanging overhead, the album’s cover zeroes in on three generations of women at which Sol is the center. In Mother, she is in direct conversation with both her mother and daughter, reflecting on the challenges of her upbringing and the celebration of bringing new life into the world. “I became a mother this year,” the singer shared on an Instagram post, “and it’s been the most transformative, uplifting, heart melting, strength giving experience thus far that led me to write this album.”

Produced by Inflo (Little Simz, Michael Kiwanauka), who produced her debut and is also her counterpart in elusive music collective SAULT, Mother is a slow, breezy ride through R&B, soul, jazz, and Latin. Sol’s voice remains the focal point throughout, influenced by Sade’s sensual ease, Stevie’s soul, and the laid-back pulse of lovers rock reggae. Though she’s not yet a household name, Sol has become a prominent name in London’s exciting new generation of alt-R&B and soul artists alongside peers like Greentea Peng, Arlo Parks, and Mahalia. If 2020’s Rose in the Dark helped claim her place as one of UK’s bright up-and-comers, Mother is a more pointed peek into the otherwise private artist’s personal life – a humble masterpiece full of grievance and glee, as pure as the mother, the daughter, and the individual behind it. — PALEY MARTIN

42. Alfa Mist – Bring Backs [Anti-]

Alfa Mist didn’t have the luxury of cutting his teeth at a conservatory. Having grown up in one of London’s poorest areas in Newham, he experimented with grime beats on FruityLoops throughout his early teens before immersing himself into instrumentals from Dilla, 9th Wonder, and Madlib (especially the latter’s Shades of Blue). The sounds nurtured a growing appreciation for sampling, strengthened a young Alfa’s interest in loops and led him to take up the piano. Eventually, his compositions became a hypnotic mix of jazz, neo-soul, and hip hop, evidenced by his acclaimed discography since his 2015 debut LP Antiphon.

His fourth album, Bring Backs, is his most complete yet. A meditative nine-track journey that evokes nostalgia while still sounding modern; it’s nocturnal music apropos for long train commutes and winding walks. From the astral “Teki” to the laid-back “Attune”, subtle homages to Chick Corea’s Return to Forever and Miles Davis’ In A Silent Way are scattered all over. You’d be forgiven for mistaking it as a classic Blue Note record from the 1960s. As well as a masterclass in genre fusion, Bring Backs also doubles as a love letter to London, with the moody “Mind the Gap” punctuated by underground Tube bulletins and the energy of “Run Outs” embodying the frantic nature of the place Alfa calls home.

Alfa’s tendency to tie his works together with profound spoken word interludes continues on Bring Backs, with Hilary Thomas’ poem about the migrant experience in Britain traveling through the record. It mirrors Alfa’s own experience as a child of Ugandan immigrants in a rough part of east London. It’s also the reason why he named the album after a rule in a homegrown version of blackjack, in which you can be brought back into the game even after shedding all of your cards, echoing Alfa’s sentiment that he still hasn’t succeeded despite his rapid ascendancy. On the contrary though, Bring Backs goes a long way into solidifying him as a key torchbearer of the UK’s next-gen jazz movement for years to come. — OUMAR SALEH

41. Ralfy the Plug – Rapper Overnight 2 [Stinc Team]

When Rapper Overnight 2 was recorded at the beginning of the year, there was a sense of hope in the air. Ralfy The Plug, Ketchy The Great and Drakeo The Ruler were all free men after a hellish few years of battling a corrupt court system and Drakeo had already exceeded expectations by dropping a seemingly limitless stream of street anthems from the moment he left MCJ. It felt like the beginning of something truly special.

Since then Ralfy has lost both his best friend Ketchy and his brother Drakeo, the former killed after being hit by a car this summer and the latter stabbed to death at an LA music festival just two weeks ago. These are unspeakable losses for Los Angeles and the hip-hop community, but even more so for Ralfy, who just lost a friend, a brother and his two closest collaborators. Rapper Overnight 2 features some of the three’s best work, doubling as proof that Ralfy can stand on his own while also highlighting the Stinc team’s classic chemistry.

Ralfy and Drakeo communicated in ways that only blood brothers can understand; Ralfy’s villainous cool always brought out the best in Drakeo—and vice versa. Almost as a response to his brothers prolific 2021 output, Ralfy released a total of five projects this year, including the Drakeo collaboration A Cold Day In Hell. The best of the bunch is Rapper Overnight 2, which opens with what’s easily become the de facto Stinc Team anthem of the year, “That’s A Awful Lot of Stincs,” featuring Drakeo The Ruler. Fizzle and Al B Smoov’s production is different from what you’re used to hearing Ralfy or Drakeo rapping over. It has a Golden Age feel that reminds me of “93 ‘Til Infinity” by Souls of Mischief and neither MC sounds a centimeter out of place. Ralfy compares himself to a recovering street skater and Drakeo proclaims that .223s have LeBron and Jordan fighting again, setting the tone for an album that feels like it was created in a rare state of harmony.

The album also features some of the late Ketchy The Great’s best verses, like on “Absolutely,” also with Drakeo, where Ketchy’s live wire energy transforms the otherwise subdued track into his own. Ketchy’s chemistry with Ralfy had never been stronger and listening to him here is a bittersweet reminder of what the Stinc Team lost with his passing. Ralfy would go on to release the stellar Pastor Ralfy later this year, which had no features aside from three songs with Drakeo. But the first glimpses of Ralfy’s brilliance can be found buried between the posse cuts on Rapper Overnight 2. “That Type Of Shit” is one of Ralfy’s strongest offerings. He has a penchant for writing hooks that bleed into verses and eventually get stuck in your head for the foreseeable future. This will always be the year that Ralfy lost his brother and his best friend, but I’ll also remember it as the year that Ralfy truly found his voice as an artist and year that the Stinc Team took over Los Angeles, cementing themselves among the greatest to ever do it. – Donald Morrison

40. Chris Crack – Sheep Hate Goats [New Deal Collectives]

Releasing projects at a furious pace sometimes results in inconsistent quality, leaving a trail of skimmable bodies of work rather than material with a lasting impact. This plague has yet to catch up with Chris Crack. The Chicago rapper moves like Lou Williams: a volume shooter who steps up and delivers regardless of circumstance. His music plays out like observational comedy routines rather than simple rap songs; the colorful bars make even mundane moments such as playing Xbox depressed sound like George Carlin rants. Even a deadly pandemic couldn’t keep Crack down, dropping four excellent projects in 2020. 2021 saw a downturn in production…only because he released three mixtapes instead of four. The best of the bunch is Sheep Hate Goats, a succinct showcase of Crack’s twisted worldview where the only solace in an increasingly bleak world is to laugh to keep from crying.

He continues his reign as the rap song title king (“Side Pussy Might Save My Marriage” sounds like the title to a new age couples therapy self-help book) and offers a healthy dose of humorous observations about society, balanced with harsh truths. On “No Romance Without Finance” he transitions from complaining about the bus to comparing white saviorism to an Aesop fable, weaving between a basic observational comic thought and a complex and poignant critique of middle America. The smokey R&B samples add to the vibe, twisting around each track like a blunt passed in rotation.

But what sets Sheep Hate Goats apart from other Crack releases is his improved focus as a writer, smoother use of samples and ability to turn regular situations like selling weed in the parking lot into soliloquies about the human condition, putting Crack in the rare class of rapper who could make reciting the alphabet sound interesting.— JOSH SVETZ

39. Colleen Green – Cool [Hardly Art]

On her brilliant Blink-182 cover album, Green transformed Dude Ranch’s crowd-ready skate rock into lonely bedroom pop by stripping down the songs to just her voice and a bass guitar. That’s a lane Green knows well, as her previous work has used that same lo-fi aesthetic (drum machines, half-whispered vocals, fuzzy riffs) to capture a deeply introverted narrator’s noisy inner monologue.

On Cool, her first full length in six years, Green and Strokes’ producer Gordon Raphael create a more expansive sonic palette that includes live drums (Brendan Eder), synthesizers (Green and hip-hop producer Aqua), and Room on Fire-ready guitars. The tasteful production supports Green’s songwriting without smoothing out her frayed edges, as if someone had nudged Liz Phair towards garage-pop instead of Top 40. Upbeat numbers like “I Wanna Be a Dog” and “Posi Vibes” bounce along like Spotify-friendly summer jams, while slower tracks like “Highway” benefit from the atmospheric touches.

Green’s lyrics continue to offer a deep dive into her own headspace. That felt like an anxiety-inducing place to be on 2015’s I Want to Grow Up, which found the singer grappling with social expectations of adulthood as she crossed the year 30 Rubicon. But here, tracks like “I Believe in Love” and “It’s Nice to Be Nice” present a newfound—and surely hard-won—sense of self-actualization.

There’s still plenty of bullshit to call out, though. “You Don’t Exist” addresses the shallowness of social media without seeming self-righteous about it. And “Someone Else” and “How Much Should You Love a Husband?” offer deeply jaded assessments of relationships—suggesting our protagonist is taking this adulting thing one step at a time.

Above all else, Green sounds like she’s having fun, and her gift for subtle melodies and attention-grabbing hooks is as strong here as ever. Hopefully, we don’t have to wait six years for a follow-up. — PETE HUNT

38. Akeem Ali – Mack in the Day Starring Keemy Casanova [Winners United]

Mack in the Day Starring Keemy Casanova was 2021’s most colorful EP, the colors in question being lavender, burgundy, and the soft-glow umber of finely brushed leather. Leaving behind the muddy waters of Mississippi in favor of a full immersion into the blaxploitation era, Akeem Ali’s Keemy Casanova alter-ego is a slick-talking connoisseur of the bell-bottomed high life. As a period piece, Mack in the Day synthesizes primary sources with lively homage: producers Othello Beats and C Gutta Beatz dress up familiar samples with bright horns, drums, and kinetic basslines, the tracks paced with narrative interludes and instrumental outros.

Ali’s chatty discursions teem with pearls of professional wisdom, his setups teeing up unpredictable punchlines. On “The Mack,” he expounds like a gold-toothed professor: “I tell h**s, don’t join if they very scary / I work ‘em year-round and give ‘em a break on the thirty-second of February.” On the lavish “Playa 2 Playa,” Ali and guest Fleetwood Fred trade verses like refugees from the Playa Haters’ Ball.

Even if Mack in the Day comes billed as a side project—a genre-work layover between Ali’s autobiographical full-lengths—it delivers the soaring heights of a main event. In one outro, Keemy Casanova submits a few backronyms for his vocation, but one feels uniquely apropos: Playa In My Prime. — PETE TOSIELLO

37. The Bug – Fire [Ninja Tune]

In the early days of the pandemic, in fact, the day before his next destination entered Lockdown #1 and shut its borders, Kevin ‘The Bug’ Martin packed up his stuff and studio, and relocated his family from Berlin to Brussels, Belgium. He describes the whole experience as war-like and emotionally taxing. Devoid of opportunities to interact with his new home turf, it was here, in Europe’s weirdest and most underrated city, that The Bug went inwards, further down a binary path that he’s been exploring for some time: one calm and subtle, the other loud and vicious. Under his public name, Kevin Martin released ambient works of escapist beauty on his own label, Intercranial Records, and a stellar rescoring of Solaris on Phantom Limb. However, after experimenting with more introspective trip-hop vibes on his 2020 project, In Blue, The Bug ran off in the other direction.

Many publications have called Fire the best Bug album to date. It for sure is his Bug’iest full-length since the 2008 classic London Zoo, in a sense that he forcefully and intentionally jumped right in his bag here. Over the years, Martin has become a master orchestrator, and it’s been a pure joy to see him go full Irishman, recruiting a cast of trusted co-conspirators – including Roger Robinson, Moor Mother, UK bashment vet Daddy Freddy, notorious grime MCs Flowdan and Manga St. Hilaire – to summon an intimately familiar storm of swathing hiss, smut, reverb and distorted kicks. It’s a world The Bug knows better than any producer in his wake, for that he has created and grown in it.

Relentless, overpowering and entirely in the red, Fire is everything a Bug fan could ask for — a timeless release that bridges the gap from the first moment he caught your ears years ago to perfectly capturing the chaos of now. The cleansing powers of fire know no trend nor era. — JULIAN BRIMMERS

36. DāM-FunK – Architecture III [Glydezone Recordings]

If your primary aesthetic leanings are forged in the heady days of adolescence, then few artists explore their influences as sincerely (and well) as Dam Funk does. Emerging fully formed onto the scene via Stones Throw at the height of the synth wave boom, he’d been re-imagining and re-inventing the sounds of early 80’s West Coast boogie and electro since high school, creating an endless sunset of lush and occasionally squiggly low-BPM jams that mined retro hardware for neck-snapping grooves, glitchy drums, robot warbles and sphincter-rattling sub-Ohm bass stabs. It’s funk as the soundtrack for an idealized Los Angeles yesteryear that never really existed, intimate yet insistent, ceaseless in its desire to connect the dots between revered elders like Zapp, Uncle Jamm’s Army or the Egyptian Lover and determined to burnish the legacy of a generation of pioneers whose innovations were subsumed into G-Funk.

Clearly, this is the work of a bedroom obsessive so it is apt that 2021 finds him in such prolific form dropping no fewer than three releases, the most insistent and head-nodding of which is Architecture III. Nominally an exploration of house music, it is testament to the richness of his sonic world that there’s little need to tweak the formula beyond gently upping the tempos and occasionally throwing in a four-on-the-floor kick. Synthesizers revolutionised music as profoundly as recording technology and with Architecture III, Dam Funk invites us to envision a golden thread that runs from Kraftwerk to the Cars to Derrick Carter and beyond, all while keeping us firmly rooted in his very specific world, the same as it ever was – a place where every drive is a convertible cruise under a cherry moon and every song the backdrop for a kiss with the Mary Jane Girls. — JOEL BISWAS

35. Altin Gün – Yol [ATO Records]

As an idea, Altin Gun read like something out of an edible-induced fever dream that you envisioned – a YouTube wormhole of Anatolian rock unspooling in your semi-conscious ears. Here is an Amsterdam-based sextet of English, Dutch, Anatolian and Indonesian extraction who play Turkish and Central Asian folk songs over arrangements and kicks so mercilessly groovy that they could leave Khraungbin or Kevin Parker ashen-faced. But beyond these absurdly hip bona fides, the best part of Altin Gun is how little any of it matters in the listening. Their US debut on KEXP in 2019 shows them in full flight and tells a story that you simply feel.

For a band with an astonishing musical palette to draw on, Yol sees them move away gleaming guitar grooves adorned by electronic sounds and instead putting the euro-disco and dream pop textures front and centre in the service of sparkling songs and stunning vocal performances, chiefly by Merve who emerges as the focal point. The result is lush, Eastern-infused electronica with shades of kitschier euro-disco and synth sounds – music that combines the hushed reverie of Beach House, the urgency of Depeche Mode, and the baroque pop of Becco Gardner (with whom Verhurst and guitarist Ben Rider were touring when the idea for forming an Anatolian-inspired band was first born.)

There are still hints of the kinetic interplay of Altin Gun, the groove machine, but the essence of their psychedelia isn’t just the transcendence of the jam but also the desire to convey unnameable shared emotions through song and melody, Yol elegantly honors that vision. To hear the band themselves tell it, Merve Daşdemir and Erdinç Ecevit Yıldız don’t choose to perform ancestral folk songs to reclaim culture or make a political point. They do it simply because they’re communal, universal and universally gorgeous.. — JOEL BISWAS

34. Aesop Rock x Blockhead – Garbology [Rhymesayers Entertainment]

As someone who started high school the same year that Bazooka Tooth came out, I’d like to think that I’ve been in Aesop Rock’s target audience since basically forever. Which is to say: Aesop Rock used to make music for teenagers, and as he got older, he began to make music for adults. If you are a college sophomore looking for a philosophy around which you can wrap your hatred of having to deliver sandwiches for Jimmy John’s, then Labor Days is absolutely the album for you. If you’re at the point in your thirties where your hangovers last longer, you go to bed earlier, and you can feel your edge slipping through your increasingly knotty fingers, then you probably want to opt for Garbology, his 2021 record with Blockhead, a.k.a. the guy who produced a bunch of the good shit on those Aes records you listened to back in college.

The first time Aes and Blockhead worked together, Rock was an avant-rap wunderkind, mostly dropping lumbering polysyllabic bars about “big picture” stuff, i.e., why work sucks ass or the fact that organized religion is a little ~crazeeee~~ when you think about it, all of which is great when you’re the aforementioned disgruntled 19-year-old Jimmy John’s employee but can get a bit grating once you’ve spent a few years in the real world. But after a few years wandering in the forests of pure abstraction, Aesop Rock re-emerged as a small-scale, slice-of-life rapper, Larry David-ing over a dude’s tacky neck tattoo and lovingly recounting how much his brother used to love the band Ministry. On Garbology, he seems vaguely more in tune with the greater hip-hop landscape than usual — if nothing else, “Wolf Piss” finds him adapting to contemporary flows which is kind of revelatory, and Blockhead’s production, while not as murky as his work on Billy Woods’s Known Unknowns, envisions an alternate universe in which trip-hop was actually one of the Four Elements, which means the beats are uniformly sick as hell. It’s nice, too, that Aesop Rock, sometimes so tightly wound within his own interiority, had somebody to work with on this one. It feels like he’s having fun, so much so that on “Jazz Hands” he (almost) straightforwardly threatens to shoot somebody in the head with a bow and arrow.

Here is what I’m saying, ultimately: This is an Aesop Rock album. You’re going to either love it or be deeply annoyed by it, nothing I type is going to make a difference, and this is POW so you can bet your ass we were gonna put this thing on our year-end list. — DREW MILLARD

33. Kiefer – When There’s Love Around [Stones Throw Records]

As the homie Boris Vian once framed it, there are only two things: love, “all sorts of love,” and the spellbinding power of contemporary jazz. Everything else can be relegated to unspeakable ugliness, the nasty shit none of us have room for anymore. Kiefer’s When There’s Love Around consolidates all the extras and brings its listener back to this binary. There’s no room to lazily pull at loose threads or misappropriate some greater sociocultural analog. This is virtuosic piano work and supremely mellow electronic modals to live with. That’s it, no catches or exceptions. It’s tight and perhaps even more purposeful than his prior work, while still retaining the Golden Hour hypnotism of 2017’s Kickinit Alone and the more inward glow of 2018’s Happysad. I spent a decent amount of my time this year walking, sleeping and doing chores to When There’s Love Around.

The wistful hum of “Crybaby” took on narcoleptic properties. The twinkly, spacious “Earthly Things” paced 2021 supermarket trips and their attendant banality/paranoia combo. This is music to think to, but don’t dare think of anything specific or actually detailed. When There’s Love Around serves up unhurried, nostalgic trance vibes when they were achingly needed. But it was also an opportunity for the San Diego-born artist to properly commemorate and mourn the loss of his late grandmother, while nodding to the stuff she put him on to (the album’s title comes from The Crusaders song from 1974).

A core of DJ Harrison, Andy McCauley, Josh Johnson, Will Logan and Sam Wilkes is a straight-up Murderer’s Row of Los Angeles jazz musicians. And though he put out another full-length in 2021, Between Days (which features a jaw-dropping rework of Roy Ayers and an interplanetary collaboration with stealthy LA beatmaker 10.4 ROG), When There’s Love Around is the most intimate music that Kiefer’s made to date. I personally owe the man for making laundry cycles more rhythmic and for making free time feel truly freeing. — STEVEN LOUIS

32. Grouper – Shade [kranky]

As Grouper, Liz Harris has made stark beauty out of obfuscated elements dating back to self-pressed CD-Rs in the mid-2000s. Her spectral recordings have transformed from found dispatches in transit between spiritual realms to minimal songs stunning in their heartbreaking clarity. Comprising songs recorded between 2006 and the present day, the guitar-driven Shade immediately evokes the immense period which produced her other two best-loved pieces, 2013’s The Man Who Died in His Boat and 2008’s enduring classic Dragging a Dead Deer Up a Hill.

For an album of archived recordings, Shade still carries fascinating diversions from what some might call “the Grouper sound.” “Ode to the blue” and its quiet longing sounds like Harris covering vintage Tiny Vipers (where empty space was its own musical instrument). “Disordered Minds” almost plays like punk rock with Harris ultimately submitting to the din of guitar noise and a drum that sounds like a cardboard box being beaten within an inch of its existence.

With Harris’ songwriting approach—that is to say “show as little as possible and tell even less”—misinterpretation comes with the territory, and Shade is prone to such activity. Whether the songs manifest themselves as rawness misunderstood as fake intimacy (plowing through blown takes on “The way her hair falls”) or atmosphere misunderstood as having nothing worthwhile to say (the gorgeous lyrics of “Kelso (Blue sky)” washed out by heavy reverb). Grouper recordings are a realm where tape hiss and the squeal an acoustic guitar makes when a player moves their fingers across the frets are as central musical components as as a chorus or finger-plucked riff.

Grouper albums are disruptive in the landscape of the singer/songwriter genre, where the markers “who, what, when, where, why” are all important keys to the enjoyment and intellectual discourse of an album. Shade, and by proxy, Grouper’s nearly seventeen years of work, introduce the idea of singer/songwriter as abstract painter, where the emotion of the work stands atop all other elements. Even understanding. Grouper songs are resonant, far-away gifts for anyone who can be in the thick of a crowd of people and still feel lonely. — MARTIN DOUGLAS

31. Sons of Kemet – Black to the Future [Impulse! Records / UMG Recordings]

In a world of artists obsessed with talking about how their new project mirrors lockdown life, Sons of Kemet deserve enormous credit for making an album which roots itself in the politics of today, without ever feeling weighed down by them. Yes, this music communicates exhaustion around existing in a world where Black death is an accepted part of the daily news cycle (“Black’s snare is a firefly dancing in grief / leave us alone” begs guest poet Joshua Idehen on powerful closer “Black”), but Kojey Radical’s howls of “I don’t fear nothing” on “Hustle” show an instinct to rebuild from the rubble.

Comprised of saxophonist and clarinettist Shabaka Hutchings, composer and Tuba player Theon Cross, and drummers Tom Skinner and Eddie Hick, the band urgently combines jazz, deep funk and Afro-Caribbean rhythms with UK grime and garage. Hutchings, the leader of this pioneering British group, shows a particularly ambitious arrangement on “Let The Circle Be Unbroken”, where his elegant melodies descend into a series of disjointed, high-pitched snarls that seem to replicate a desperate struggle between a cop and a protestor. But Cross, who sounds less like a jazz musician and more like Doug E. Fresh beatboxing in a street cypher, lends these songs a resilient bounce. This juxtaposition of styles results in a tug of war between dread and joy, with the latter tending to prevail.

By embracing such a hip hop sensibility throughout Black to the Future (grime pioneer D Double E is tellingly among the guests), Sons of Kemet bring a new generation of rap fans into the arena of jazz and wake them up to its similar ability to prompt societal change. — THOMAS HOBBS

30. Patrick Shiroishi – Hidemi [American Dreams Records]

The opening notes of Patrick Shiroishi’s Hidemi hit like a tornado siren. Come unprepared, and the saxophone shrieks will have you jumping from your seat. It’s a clarion call from the deep recesses of the album’s origins, which begin to unfurl themselves both in the brilliant and vast landscape he paints and the urgency with which he tells the story of his grandfather, for whom the album is named.

Instrumental music is inherently reliant on outside sources to reveal themes, motifs, and philosophies, so a bit of background on Shiroishi’s approach is helpful. The Bandcamp page for the album states, “As Patrick’s name is in memory to his grandfather, Hidemi is too, and across the album’s nine tracks, Shiroishi brings the listener through tension and release, showcasing something unfiltered, beautiful, and ultimately hopeful, a testament to perseverance and grace.” The grace Shiroishi conveys is that of a Japanese-American man thrown into an internment camp, and through the album’s nine songs, Shiroishi uses a stunning and at times aggressive variety of saxophones, effects, and techniques to tell this story.

“Tule Lake Like Yesterday” begins with two horn lines intertwining like vines on a fence before Shiroishi slowly, expertly places horn after horn atop the initial composition, stacking sounds individual enough to stand out but interlocked nevertheless. The album’s centerpiece is its closer, “The Long Bright Dark,” perhaps a nod to what freedom means when one knows what freedom costs. The track quickly ascends to a cacophony of sax parts and screaming vocals. It grasps at an elusive center that never quite reveals itself, though Patrick Shiroishi will surely continue to excavate its layers in hopes of finding peace through justice. — WILL SCHUBE

29. Anz – All Hours [Ninja Tune]

Manchester U.K. DJ and producer Anz started out making sort of neon lined grime back in 2017. Since then, she’s released a number of records, put out a popular mix series, appeared on BBC Radio One and NTS and started her own OTMI record label, all pushing her dance floor shaking abilities ever outward. Yet nothing to date has been as colorful, fun and joyous as All Hours.

Anz likes dance music, and not just from one particular style from one very particular time period, from one particular label, no. On All Hours she wants you to know that she likes it all, and she wants you to like it all too and to appreciate dance music’s full scope too and stop being a purist, Comic Book Guy weirdo about it.

Tracing the feeling and progression of an all night rave, the six tracks on this EP (two of which are intros and outros respectively) incorporate everything from big disco style vocal anthems (with help from spirited vocals by diva house star in waiting George Riley), sweaty UK garage and two step numbers, limber Baltimore/Jersey club breaks, ricocheting UK dubstep drums, Miami bass raunchiness, lushess NY house synths, and classic rave sounds from cheesy trance to pounding drum and bass. Sometimes all in the same song. And as a treat, the denoument sounds like some My Dark Twisted Fantasy era Kanye West and Mike Dean type outro. What’s not to like? There’s something for everybody. — SAM RIBAKOFF

28. Doja Cat – Planet Her [Kemosabe Records / RCA Records]

Exactly what a Pop Rap album is supposed to sound like in 2021 (or maybe 2025) , Doja Cat’s Planet Her brought both commercial and critical returns.From the moment she first caught everyone’s attention with 2018’s trollish novelty effort, “Mooo!’, it was obvious that Doja Cat was going places. The only questions were how high she’d go and how much of herself she’d get to keep during the journey. Planet Her confirms that the answers are “to the top” and “as much as she wants”.

The L.A.-raised pop star is an internet-steeped musical polymath on par with Jamie Foxx, Donald Glover, and anyone else capable of snagging an EGOT. She’s seemingly been fully formed since her debut and Planet Her doesn’t prove anything that wasn’t already true three years ago. A cat of all trades and a master of all.

A loose concept album about “the center of the universe” where “all races of space exist and its where all species can kind of be in harmony,” Planet Her has a hit for everyone and for once, the Grammys aren’t wrong to have bestowed her with eight nominations. She blends rapping, toasting and singing over Afropop beats, and nails ballads and chants. She gets her trolling in via “Ain’t Shit” and the pseudo-dick joke that is “Need to Know.” She sounds comfortable (even dominant) next to the leading pop vocalists of the era and some of the most inventive rappers alive, but you get the sense she’s only working with them because the label asked. She doesn’t need any of them. We’ll be on Planet Doja for as long as she isn’t bored with making music. All hail the new Queen; long may she shitpost and show feet. — MOBBDEEN

27. Maxo Kream – WEIGHT OF THE WORLD [RCA Records]

WEIGHT OF THE WORLD is a heavy listen. Its heft reads in the thunderous kick drums and bulky gait of Maxo Kream’s locked groove. Most of all, it calcifies the nebulous, nonlinear ideas of grief and anguish– to absorb its brutal honesty feels like deadlifting a thousand pound barbell. It’s not preachy though. Maxo isn’t here to moralize. The mining of his caustic past—tales of gang violence, homicide, familial conflict, and generational trauma—is meant to be more of a healing tonic than a warning parable. Maxo himself likens making records to therapy—in an interview with The Fader, Maxo remembers recording “TRIPS,” a detailed account of his brother’s murder, two days after it happened.

As Punken and Brandon Banks showcased his growth into a vivid storyteller, WEIGHT OF THE WORLD finds Maxo in top form. He raps in strings of declarative sentences, painstakingly detailing snapshots of memory. Album highlight “GREENER KNOTS” flashes back to his childhood, twisting the memories of his first time seeing a crack rock or firing a gun around deceptively simple rhyme schemes. “MAMA’S PURSE” uses a latticework of internal rhymes to tell a story of petty thievery that spans several generations. Maxo doesn’t cloak his pain or triumph in metaphor; he looks you dead in the eye and explains what’s what.

The album’s elegant production provides a plush landing pad for Maxo’s weighty narratives. A native of Alief, a mostly poor and working-class neighborhood in southwest Houston, Maxo dresses his songs in the stylistic markers of his hometown: molasses-drip tempos, trunk rattling bass, the mechanical churn of pitched-down 808 snares and claps. His flows generally stick to a rigid eighth-note march, occasionally tumbling into an unbreakable triple time.

The production team, headed up by frequent collaborator teej, sands down these taut edges. The beats are simply gorgeous, blooming with luxurious string samples, rippling xylophones, and the multipart harmonies of lowrider soul. Even when the subject matter is intense, the album never feels dour. These are songs of forgiveness—of oneself for past mistakes, of parents for making harmful choices in the name of family stability, and of anyone who doubted Maxo’s potential for greatness. — DASH LEWIS

26. Ka – A Martyr’s Reward [Iron Works Records]

Modern technology gives everyone a megaphone but Ka still performs like the austere village elder, dispensing pearls to those curious enough to duck out from the screaming throng and listen. He tells his story shorn of descriptors so as to make it timeless and universal, but it is unmistakably his story with his grief and his lessons.

Ka depicts the Brownsville of his youth as a place of poverty and desperation that imparted on him a few cherished principles. Friends, family, and neighbors share in the struggle. Making money is an existential necessity – handwringing over it is an ill-afforded luxury. Public institutions should be regarded warily. Nothing comes easy.

In his previous opuses, Ka borrowed motifs from antiquity to animate his subject matter – the bushido, the Bible, Greek myth. This time, he employs no such dramatic devices. With a voice like dry leaves, Ka renders inner city black America with a colorless desolation more typical of science fiction than crime drama or bildungsroman. Circling 50 years of age, Ka finds plaintive elegy more compelling than Hollywood theatrics.

“Subtle” on the back half is akin to a hymn. He hints at it elsewhere, but this is where Ka takes stock of what the torturous environment of his upbringing made of those who survived. With evident pride, he describes the character of a community where people had to maneuver for their next meal and guard their keep with military arsenals. Having made it to the other side, Ka claims resilience and obstinate determination as his rewards.

Ignore the voyeurs, the ideologues, and the fabulists. Listen to Ka. — EVAN NABAVIAN

25. BADBADNOTGOOD – Talk Memory [XL Recordings / Innovative Leisure]

Where IV played with the idea of time as a construct, Talk Memory is a conversation between one’s present, past, and future self. BADBADNOTGOOD creates the looking glass in which their listeners can view the world as a continuum, interweaving notes of nostalgia and forewarning within the present moment. “Signal from the Noise” is dark and foreboding, with a Stratosphere-like, space-rock presence to allow your mind to drift into the world of Chester Hansen, Alex Sowinski, and Leland Whitty. Brooding conversation stirs between the musicians and a pondering excitement ensues; it’s a readiness to delve deeper into your psyche, as demonstrated with a fluttering saxophone and the flutist’s four-note, trance-like phrase.

In their most orchestrated project to date, BADBADNOTGOOD excels in encapsulating the freedom that comes with introspection. “Unfolding (Momentum 73)” is thermal and kaleidoscopic, breathing psychedelia with meditative harp strums and the legato swirls of an alto saxophone. Consider it the waiting room – the Cartesian theater in which you decide which memory will be uncovered next. With aid from the brilliant Brazilian composer, Arthur Verocai, “Love Proceeding” is the black-and-white, intimate soundtrack of the ‘60s, or perhaps your parents reminiscing about their adolescence and the adversities they faced growing up. “Besides April” is sweet and heart-racing, bracing the handlebars when it was your first time on a rollercoaster that rides upside-down.

At their roots, BADBADNOTGOOD’s most vivid memory is “City of Mirrors.” The music video has the warmth of a slightly-singed film camera, capturing the DIY scene and the band’s desire to be as free-form as possible. Everchanging, like the industrial grid that metropolitan-city skaters board through, BADBADNOTGOOD refrains from labels. Whether it’s hip-hop or jazz, they’re composing the score for conversations about the memories of the past and the uncertainties of the future. — YOUSEF SROUR

24. Burial – Shock Power of Love EP [Keysound]

British producer Burial is prophetic. Coming out of the Bush-Blair years and into the Obama-Brown years the world seemed, maybe, a little hopeful for a sliver of time when Burial dropped Untrue, an album of dystopian gray concrete dubstep and UK garage pierced with disembodied and distorted ghostly R&B samples under layers of spectral, ominous, ambient textures. It’s like he smelled it in the air. The 2008 recession, the multiplication of murderous authoritians, mass survilence, alienation, etc. BBC documentarian Adam Curtis called Burial’s music “the mood of our time that we’re waiting for,” and folks, if that’s true, good news, because on this four track split EP, Burial and his pal Blackdown are seemingly feeling pretty optimistic and ready for MLK’s idea of love to win the day.

“Dark Gethsemane,” (a reference to the Garden of Gethsemane where Jesus went to pray and find solace before he was arrested and crucified) starts as a very Untrue-esque brooding beat, until halfway through the ten minute track, a voice announces “to start a new world,” and then launches into a loop of someone who sounds an awful lot like a certain reverend who spoke at the 2016 Democratic National Convention (no sample snitching though) exclaiming “We must shock this nation with the power of love!” As the track builds, other voices join in, and genuinely uplifting choral synths lift the track to that upper room, which introduces a minute long, almost fist pounding, disco beat that sounds like a Jessie Ware outtake.

Blackdown’s tracks and Burial’s other track, even when it gets a little submerged in murky textures, follows that optimistic and almost ecstatic house vibe. It’s refreshing, and even though you don’t want to give in to false optimism about the future,try listening to “Space Cadet,” without feeling something close to hope. — SAM RIBAKOFF

23. Young Slo-Be – Slo-Be Bryant 3 [KoldGreedy Entertainment / Thizzler on the Roof]

If it wasn’t obvious from the title, there are plenty of basketball references on Slo-Be Bryant 3, and at a rate of speed that hasn’t been seen since Sada Baby compared his shotgun to Lauri Markannen. When was the last time you heard a Latrell Sprewell name-drop before this tape? The Stockton, California native gets his moniker from literally just adding “Young” to his father’s name, and wields a smooth, laidback flow that allows him to easily blend his casual mentions of violence with hilarious contemplations of mundane, everyday situations. (“If she ain’t mine I ain’t got time / Free the thugs, you know they got time.”)

Slo-Be Bryant 3’s 21 tracks—a number that feels like it can’t be a coincidence, as Slo-Be shouts out his hometown block 2100 on nearly every song—are littered with features from other artists across the state like Sacramento’s Mac J and several other Stockton artists that have made waves like EBK Young Joc. But it’s Drakeo the Ruler who unsurprisingly steals the show on “Unforgettable”, as he matches Slo-Be’s flair for references with lines like “thirty-four shots, Paul Pierce, pick your jaw up”.

So much of Slo-Be Bryant 3 feels like a hometown operation—a majority of the features and the project’s producers all hail from southeastern Stockton, California. And yet, it’s easy to pick out elements of the Bay Area, Atlanta, Michigan, the DMV; here, Young Slo-Be has taken familiar sounds and synthesized them into something wholly belonging to and instantly recognizable as northern Cali. If the NBA ends up shutting down again this season, at least Young Slo-Be will have enough player references to tide us over. — MARCO KANE

22. La Luz – La Luz [Hardly Art]

La Luz, arguably in the top percentile quality-wise of American rock bands today, has long walked the tightrope between the radiant and the haunting, between cuddle jams in the sun and foreboding devotionals from dark places. Luxurious three-part harmonies exposing sinister forces or acting as the sirens in kaleidoscopic dreams. Ripcord guitar solos unfurling violently over the elegant rhythm section. Motherhood has informed the direction of the California group’s self-titled album as any other influence, with frontwoman Shana Cleveland penning odes to her young son foremost, with a little danger lurking in the background on songs like “Metal Man.”

Already having worked with some of the most celebrated rock producers just south of the mainstream line (Ty Segall, Dan Auebach), La Luz enlisted the services of Adrian Younge. Younge’s production, which is just as suited to widescreen, Mid-Century Modern surf-rock as it is to technicolor R&B or spaghetti western hip-hop, shines here; casting the band and its songs in crystalline sunlight and vivid splashes of detail.

The album’s 37 minutes are long on balladry with almost barely perceptible psychedelic flourishes: the lovely, nostalgic mid-tempo bangers “Watching Cartoons” and “Down the Street,” the eerily beautiful “Lazy Eyes and Dune,” the dreamlike “Old Blue.” Its tunes are love songs through and through, but not necessarily the type of romance used to sell bouquets of supermarket roses. They’re about the vivid moments of being with whomever you love—friend, child, grandparent, whoever—where the world inside your mind opens up and you’re able to look at love from a uniquely elevated plane. La Luz is yet another profoundly graceful album from a band that couldn’t sound raggedy if they tried, a monument to the very essence of love. — MARTIN DOUGLAS

21. Wiki – Half God [Wikiset Enterprises]

Half God is the record that has lingered in Wiki’s subconscious since the earliest days of Ratking, maybe even since he was a kid in Manhattan bumping Mobb Deep and Wu and Dipset. Unlike his previous records, which injected East Coast formalism with icy, litefeet electronics, Half God digs its fingers into the soil of soul loops. These beats, courtesy of New York polymath Navy Blue, are warm, post-Marcberg creations–not quite revivalism, but still indebted to a rich lineage of true school-rap. Wiki continues to rhyme about New York with an almost religious fervor. Together, their work paints the city in sepia tones, reckoning with what it is and yearning for what it was.

What’s interesting about the Wiki-Navy Blue pairing is how both have navigated the prestige media profiles and local rap circuit without compromising their sound. Half God has popped up on countless year-end lists, yet doesn’t have a song as catchy as 2017’s “Mayor” or show-stopping as the Madlib collab “Eggs.” It’s a dense body of work, raps on raps on raps, that unfurls as a series of vignettes. There’s the story of the drug supplier who betrays his family; the sights of little ant-people from Wiki’s roof; the scathing critique of out-of-towners that interpolates Ludacris’ “Move Bitch.” There’s an allegiance here to the sort of conceptual writing you’d expect from a New York rapper 25 years ago.

The joy of being a Wiki fan since the Ratking days has been to hear him grow up. In recent records like 2019’s OOFIE, there’s a fascinating tension of hearing an old soul who had a buzz in his teens navigate his late twenties. Half God builds on that feeling–hear how Wiki describes feeling detached from himself while touring on the somber “Promised”–but that tension is cut by how Wiki burrows into these samples like they’re pillows. For every bitter assault on gentrifiers, there’s a gulp of grape soda, a bit of tongue-twisting whimsy. “When I make a remark, remark remarkably.” Half God dwells inside a beautiful mess tinged with sadness, an analogue to the city Wiki calls home. – MANO SUNDARESAN

20. Remble – It’s Remble [Warner Records]

Remble begrudgingly shells out bits of game and veiled threats, acutely aware of the corniness looming over every interaction, both online and in real life. His debut album, It’s Remble, introduced an enunciated brand of nervous rap that’s unique and easily distinguishable from his LA contemporaries, establishing the San Pedro native as one of the most sought after rappers in the region.

Seven of the 13 songs on It’s Remble had been out on Youtube before the official release, including two of this year’s best singles, “Gordon R Freestyle” and “Touchable.” These were the kind of songs I rushed to show my skeptical, old head rap friends as proof that not all new hip-hop is bullshit. Remble’s matter-of-fact flow and unique approach to songwriting sounds like no one else right now. He refers to himself in third person and speaks directly to his listeners with “you” statements. The Undertaker bell toll at the center of “Touchable,” produced by -10Fifty & Jaasu, conjures up images of Remble in a dark graveyard burying someone alive. On “Gordon R Freestyle,” Remble drops enough witty one-liners to be crowned as hip-hop’s Mitch Hedberg. Earlier singles featured on the album include “Never Tell,” an early standout where Remble says he stashed a murder weapon in “Bikini Bottom” and announces that he keeps his foot on more necks than Derek Chauvin.

It’s Remble more than made good on the promise of those early singles and introduced us to B.A., Remble’s dexterous sidekick who managed to hold his own on “Audible,” one of Remble’s best songs to date. Remble’s popularity has only continued to grow in recent months. He released “Rocc Climbing,” with Lil Yachty, that has since inspired numerous TikTik dances and continues to go viral. It makes him seems destined for the kind of stardom only reserved for the truly singular and this is the album we’ll look back on as starting it all. — Donald Morrison

19. Faye Webster – I Know I’m Funny haha [Secretly Canadian]

Faye Webster’s calling cards—vulnerable lyrics, twangy vocals, playlist-ready vibes—are front and center on I Know I’m Funny haha, the 23-year-old singer’s standout fourth album, and second since signing with Secretly Canadian. Her typically strong songwriting is given extra punch, however, by a crack team of Athens-based musicians and producers, who help Webster deliver the best sounding record of her young career.

Studio savant Drew Vandenberg (who also helmed 2019’s Atlanta Millionaires Club) is once more behind the boards, and he and Webster again settle into a Stax Records-inspired soundscape that seamlessly blends alt-country, indie pop, and neo-soul. Matt Stoessel’s pedal steel guitar and Nick Rosen’s keyboard textures are the most prominent instrumentation, but it’s the little percussion flourishes sprinkled throughout—the guiro on “Kind Of,” the triangle on “Both All The Time,” and what may be a sand shaker (!) throughout “Overslept”—that really convey the album’s craftsmanship.

Webster was previously signed to Atlanta’s Awful Records and has contributed interesting hooks to songs from Ethereal and other affiliated artists. That experimental influence is largely absent from this record, but she does offer a few stylistic left turns. “Cheers” leans heavily into a 90s alt-rock sound and would have fit perfectly on the Romeo + Juliet soundtrack. “A Dream With a Baseball Player”—a TikTok-ready torch song about Braves outfielder Ronald Acuña Jr.—is supported by horns you’d swear were lifted from a Sade deep cut. And the aforementioned “Overslept” features Japanese vocals from singer mei ehara.

In addition to her many other talents, Webster is also a photographer, and her lyrics demonstrate a similar gift for capturing fleeting moments with memorable framing. She confesses to getting loneliest at night “after my shower beer.” And the bass guitar she buys her boyfriend for his birthday is “the same one the guy from LinkedIn Park plays.” These telling details, often delivered in a light and airy falsetto, add texture to familiar expressions of melancholy, and help I Know I’m Funny haha land as one of the year’s most accomplished records. — PETE HUNT

18. Bruiser Wolf – Dope Game Stupid [Bruiser Brigade Records]

There are certain axioms so pithy that, once spoken, their truths become self-evident. A penny saved is a penny earned. Scared money don’t make none. The dope game stupid, but the boy still do it. Bruiser Wolf’s debut Dope Game Stupid is packed with declamations ranging from the inane (“Flirtin’ with a w***e wearin’ Dior, this a Christian mingle”) to practically psalmic (“Right way, left way, where ya goin’? I’m here for the commas, period, semicolon”), the combination of similes, enunciation, and production making for a genuinely synesthetic experience. “Bottles of Anejo” announces a menu including “pockets full of queso, coke white like alfredo”; producer Raphy’s beats are like Motown instrumentals reflected through a foggy fun-house mirror.

Wolf raps like the offspring of K-Dee and E-40, yet Dope Game Stupid’s vividness conceals the humane depths of Richard Pryor’s methods. On “Momma Was a Dopefiend,” Wolf recalls a home life that “left my dad bitter, like grapefruit”; he tells his schoolmates that his mother works at the zoo rather than admitting to his grief. There’s an eagerness to please, a desperation to be heard, underlying Dope Game Stupid’s raucous comedy. These are the tears of a clown: you couldn’t look away if you wanted to. — PETE TOSIELLO

17. Pink Siifu – GUMBO’! [Dynamite Hill]

Pink Siifu is one of rap’s most chameleonic characters, with an ever-shifting muse that leads him to routinely bend the genre around his center of gravity. Over the last couple of years, he has chased visions of striking jazz punk protest, shit-talking spiritualism over dusty soul loops, and now a career-best statement that recreates the spirit of the Dungeon Family but steeped in the swamp. GUMBO!, true to form, sounds like no other Pink Siifu record. But it also sounds like no other album released this year. Testament to his seemingly limitless capacity, Siifu strung together a defiantly post-regional collection with a distinctly southern flavor, with notes of D’Angelo chopped and screwed, a post-MFA Playboi Carti, and G-Funk processed through a South Florida filter.

What’s remarkable then is how cohesive and easily digestible it all feels. Whereas last year’s Negro was intended to be impenetrable, GUMBO! is crafted like a communal meal. The most singular talents of underground rap – Liv.e, Bbymutha, monte booker, The Alchemist, and many more – are all invited to lend their touch to this hearty spread. As the host, Siifu himself is often content to remain buried low in the mix, his syllables blurring in and out within the larger collective of voices. But the album rewards close listening, with moving portraits of family and hard-earned perspective running through the rich broth, one that feels drawn from the same family of recipes that connects the Soulquarians all the way back to the Parliament-Funkadelic. You can hear Siifu’s reverence for history, but also his willingness to go beyond homage. The result is an immersive world that sounds equally familiar and surprising, layering tradition with radical ideas that keep the sonics from going stale. — PRANAV TREWN

16. Dean Blunt – Black Metal 2 [Rough Trade Records Ltd]

Since releasing Black Metal in 2014, the enigmatic British singer and producer Dean Blunt—when not stealing raccoons from a taxidermist or selling a weed-stuffed toy car on eBay—has put forth more musical iterations of himself than many artists can fathom in their careers. He has recorded several grime-meets-hip hop projects as Babyfather, contributed to A$AP Rocky’s Testing, wrote and directed the opera Inna, released a twisted lo-fi electronic duo record with Delroy Edwards, and played on Blue Iverson’s funky, smooth jazz fusion Hotep.

Black Metal 2 is a return to the relatively straightforward pop he explored in Black Metal. At just over 20 minutes, the sequel is a tight, spare, stripped-down set of ten songs that juxtapose gritty lyrics against strummed guitars, subtle synths and bass, and minimal rock drums. The music could almost be straight out of a brooding indie rock record. On the jangly shoegaze “DASH SNOW,” Blunt croons that “it’s gonna be alright.” Is he out to reassure us or does he need convincing himself? As if what other choice is there than for everything to be alright? But later it’s clear that Blunt knows better, as he sketches people living in the bleak shadows of society’s margins who are down to their last option. On six tracks Blunt’s frequent collaborator Joanne Robertson’s spacey reverbed vocals counterbalance his short, matter of fact lines. Blunt sings right at the bottom of his vocal range—any lower and his voice would crumble and blow away. He comes off as vulnerable, nearly broken, and—for all the obfuscation around his music and persona—genuine. If we didn’t know better, we might think that this is the version of Dean Blunt with nothing to hide. — CHRIS ROBINSON

15. Rochelle Jordan – Play With the Changes [UNDRGRND Records]

Rochelle Jordan has made a career out of exploring intimacies. Her vision of R&B is aimed squarely at the dancefloor, but she’s hardly a house belter. She tends towards a more subdued approach, nestling her vocals inside the pockets of drums, layering harmonies only to slip between the keys of a passing synthesizer. The approach tracks; she grew up with the sounds of house and drum-and-bass pouring through her walls. This is R&B for the club, but Jordan writes with such specificity that she might as well be singing to an audience of one. Her music lives in this liminal space: personal stories draped atop communal joy.

“Love You Good,” the record’s opener, sets the scene with dreamlike synthesizers and rapid-fire drum-machine patter: a night out and the 4-a.m. drive home played out simultaneously. She sings at a bit of a remove, sounding downcast even as the bass surges underneath her tightly held harmonies. Much of Play With the Changes works like this. Lapel-grabbing lyricism jostles against shimmering dancefloor elation in one moment; the next, quick-hitting drums offer an undergirding for slow-motion vocal runs. The production is similarly kaleidoscopic, jumping between slicked-up drum-and-bass, slippery 2-step, and chunky house.

Nine tracks in, Jordan finally turns the lights on. “Lay” contains her most striking performance on the LP: she flips any paeans towards dancefloor intimacy on their head, instead begging a lover to stay home in a world likely to gun them down. Nowhere else does Play With the Changes breach those life-or-death stakes so explicitly, but that bruised core nevertheless runs through the rest of the record. Never mind the rip-roaring rhythms: Jordan is deep in her own head here, desperately holding onto who she has even as she imagines escape hatches and lingers on past transgressions. On Play With the Changes, she combines the joys of a great night out with the hushed intimacy of a whispered conversation between lovers. The result, rendered with striking clarity, is club-night melancholia that weaves between people, sounds, and feelings, blurring them all into something wholly new along the way. — MICHAEL MCKINNEY

14. Isaiah Rashad – The House Is Burning [Top Dawg Entertainment]

Isaiah Rashad may not have even found his lane yet, which might be the most exciting thing about him. It feels like he’s been around forever at the fringes of Top Dawg Entertainment, not quite mysterious enough to be a Jay Electronica level enigma but absent enough to tease your imagination into wondering what could be.

The House is Burning, Rashad’s 2021 release, feels like the start of something sustainable. There’s very little searching on the record, save for the obvious intellectual curiosity underpinning each of Rashad’s mumbled non sequiturs. At first blush, the title feels like a tongue in cheek commentary on our global state of affairs, but the sound is breezy and nonchalant. The record glides through its runtime, Rashad a collected spirit guide whispering shapeshifting meter over jazz that sounds like it could’ve been on the cutting room floor of Do The Right Thing’s soundtrack. Never a flashy lyricist, Rashad’s work here is about aesthetic, evocative of someone who knows he seems lost to the outside observer but feels comfortable wandering the woods. His southern drawl adds an unexpected twist to what has become TDE’s signature sound: the melding of G-Funk, Yacht Rock keys, extraordinary bass lines, and samples curated to honor the greats but with a touch of Rocky Top instead of Crenshaw. Rashad makes little mention of his past, letting the sound itself add a sort of unplaceable depth to the sly turns of phrase; an umami of sorts where the indescribable sensation is that you’re listening to someone who is worth the time to truly stop and hear.

Through it all you’re reminded that we’ve been here before. If you’re still alive in America, it’s because somebody suffered to get you here. It’s your turn now. — CASEY TAYLOR

13. Erika de Casier – Sensational [4AD Ltd]

This is what a great 2000s pop album would sound like if it was recorded in 2021. Born in Portugal to Belgian and Cape Verdean parents and growing up in Denmark as one of few Black children around, Erika de Casier has talked about the sense of cultural dysphoria that comes with being one of the only people in your community that looks like you in your formative years. She found something firm to latch on to in the R&B music of the late ‘90s and early ‘00s, right when artists like Aaliyah, TLC and Destiny’s Child were writing themselves into the pop music canon. Sensational is an earnest recreation of that era, with its bent for twinkling synth instrumentation and pop-perfect one-liners. In her own videos, de Casier takes on an alter ego, Bianka, who feels like someone plucked out of time from the extras casting for Nelly Furtado’s “Promiscuous” video. I’m texting Bianka to link up through Excel on my Nokia flip phone.

The nostalgia of ‘90s kids has proven to be a potent and also greatly profitable force, leading to a lot of bad pastiche and other biters looking for an easy opportunity to cash in. De Casier isn’t that. There’s great and genuine appreciation in her music, but she ties her influences together to form something that feels fully her own in album-length. Even when it’s kitsch, it isn’t lazy.

For most of the album, de Casier voice rarely flutters above a whisper. She occupies that softest part of the vocal register that licks at the inside of your ear or rolls down the back of your neck. Sensational is a tremendously sexy album, but it isn’t an album about sex, per se. Instead, de Casier focuses on the earlier stages of romance, where you don’t know what the thing is going to be and everything bounces with a sort of low-stakes playfulness. There is, consequently, a lot of music about shitty dates, but it’s never too serious. On “Polite” — one of the funnier songs I listened to this year — there’s obviously enough romantic interest, if the guy would just use his manners and stop being a dick to restaurant staff. It’s fun, without really thinking too much. In that sense, it really does remind me of the 2000s. — KEVIN YEUNG

12. Unknown T – Adolescence [Stay Solid Music / Island Records / Universal Music]

UK Drill is perhaps the single most underappreciated musical scene in the world today. New York jacked its beats, British law enforcement harasses its artists, and journalists continue to be more concerned with spreading moral panics than amplifying its sonic accomplishments. That alone should convince you to listen to Unknown T’s Adolescence, a brilliantly mournful collection of street chronicles, mostly ignored by the mainstream music press. But beyond being a great record, it also signals an end point for one of the most discussed concepts in British music: the Hardcore Continuum.

Briefly, The Hardcore Continuum is a theory proposed by music writer Simon Reynolds, positing that Hardcore, Jungle, UK Garage, Grime, Dubstep and UK Funky were all part of the same musical lineage, with the same working class, multi-cultural audience. It’s a theory that remains in use, but to my ears, it no longer holds water, as the UK dance music proposed as heir to the continuum land closer to the brainy experiments IDM than rudeboy Jungle. Simultaneously, Black kids across the UK have doubled down on rhyming, with songs breaking on YouTube rather than nightclubs, and dance tempos optional.

Adolescence intensifies all of these trends, borrowing sub bass from Jamaica, 808 patterns from Atlanta trap and Chicago drill, warping synths from hrime and even Middle Eastern and East Asian sounds from dubstep. It should be the continuum’s next step, but just as importantly, it rejects the idea that these musical signifiers need be used in dance music at all. Instead, Adolescence and by extension Drill, puts the hard back into in hardcore, delivering grim narratives to reflect on rather than grooves to dance to. That hasn’t earned it many fans in the critical establishment, but it has allowed Unknown T to make a great album, one that says more about contemporary life in the UK’s estates than a dance song with an old sample ever could. — SON RAW

11. PinkPantheress – to hell with it [Parlophone Records]

PinkPantheress has a way of making you feel fragile, as though heartbreak is always just an inch away. Her U.K. garage sample repertoire runs deep, but the music stands out more from the way her voice situates itself over the rolling drums and hard-headed bass. It’s a silicon covering, an ooze that both surrounds the beats and somehow infuses itself in the ripples.

The pulsating bass patterns feel like heartbeats in and of themselves whikle the airy vocals give them life, pumping that spark that turns something from an isolated piece of flesh to the vital system that holds the magic of human life together. And for the 20 year old singer from the U.K., it’s teetering on the edge and always in danger of falling apart. The fragility of the heart, and human life itself feels omnipresent through to hell with it – maybe it’s the clipped nature of the songs flickering in and out in under 90 seconds, maybe it’s the mournful feeling of the modern malaise that inundates songs like “nineteen” and “Pain” with a preternaturally matured teenage angst, and maybe it’s the confluence of Y2K nostalgia for the “lost futures” that theorist Mark Fisher popularized.

But really, it’s that her music teems with the sincerity of a young woman finding herself in a collapsing hellscape, seeking solace in making K-Pop fan edits, investigating reddit forums, and grafting reasons to live from her notebook to the bedroom mic. It’s imbued with a sense of pride in her spiritual mp3 sessions with the revolutionaries of garage and DnB beats like Shy FX, Adam F, and Sunship. The album is mystical, but not out of touch; homage, but without the stale recycling that so many artists fall victim to. Truly, what makes it special, is simply that it just feels real as hell. — HARLEY GEFFNER

Unranked (2020 Release): Playboi Carti – Whole Lotta Red [AWGE / Interscope Records]

The minds of vampires work in mysterious ways. Before recording the album we heard on Christmas 2020, Playboi Carti crafted a version of Whole Lotta Red more in tune with our reality. As it goes in Carti land, demos from those sessions leaked in a steady drip for months, hooking fans on the prospect of a drifting, psychedelic follow-up to 2018’s Die Lit. One leak, unofficially called “Molly,” suspends itself over somber harmonies, a Dreamcast dirge trapped in purgatory. Carti, full of helium, keeps croaking something about his diamonds. Our grip on time is a function of cause and effect, of things resolving. This song teeters in perpetuity, dunking time in amber.

In 2019, when asked by The Fader’s Ben Dandridge-Lemco if he was done with Whole Lotta Red, Carti said, “I could be done if I wanted to.”

The record we heard on Christmas did not sound like 2019, or 2020, or Die Lit or the future. It did not cast spells on space-time. Instead, from its very first moments, Whole Lotta Red grounds you deep inside your body. The opener “Rockstar Made” doesn’t levitate like previous Carti intros; it pulverizes you like a piece of meat with its bone-crushing bassline. Several songs in, it suddenly feels like you’re in touch with every strand of tissue, every nerve and muscle of your existence.

Something changed. In the months leading up to Christmas, Carti scrapped most of his ideas. Alongside his go-to guys Maaly Raw and Art Dealer, he called up Working On Dying’s pioneering tread producer F1LTHY, and a couple loop-making wizards from the Netherlands named Starboy and Outtatown. Kanye West took a break from tax evasion to lend an ear as executive producer.