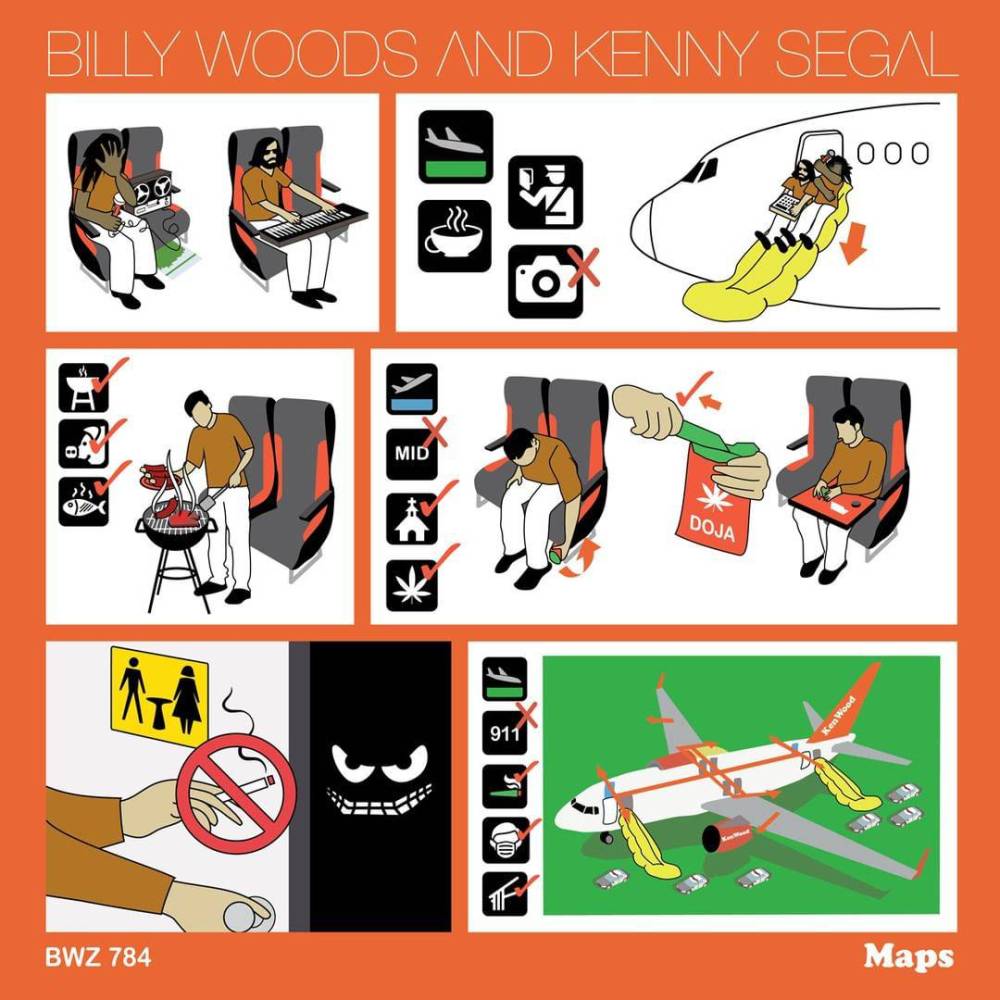

Image via Backwoodz Studioz/Instagram

Separated from being in immediate music media, Donna-Claire has become someone who grows beets and strawberries, and listens to music with more ferocity and intention.

No less than five minutes into his new album with producer Kenny Segal, billy woods raps, “A single death is a tragedy, but eggs make omelets.” As a listener, an informed member of our crumbling society, I could easily turn off Maps right there, not even 30 seconds into the second track “Soft Landing” and get it. And so it goes that when I think of billy woods, a New York rapper who has finally been heralded as the underground hero of our cultural moment over two decades into his and his label’s career, I am so often trying to solve a puzzle. I am constantly guilty of sinking into the music, not as a listener but as a curious observer. This practice obfuscates the point of listening to billy woods rap.

The bramble of his language is not meant to necessarily challenge the listener, but is meant to showcase the depth and possibilities of hip-hop. When I write about, or think about, woods, I understand that for as utilitarian and ineffectual as English is, he has turned the spoken word into the sharpest of daggers. He’s a cutting writer. And perhaps more importantly, his delivery is second to none when it comes to brain-splitting conviction.

In 2017, when I first spoke with woods, we talked for three hours on the phone. He bucked my attempts to unravel his work and instead drew a narrative where the work was an entity unto itself. Meaning, the music was a body unto itself. No need to pick it apart. It beckons the inquisitive ear, sure, but the inherent desire to intellectualize woods shrouds the truth that he’s one of the most deceptively emotional (and hysterical) rappers alive.

When I write about billy woods, I forget the gruff scythe-like voice. It’s a damn shame too, because woods cries on the mic with the same caliber of intensity as Juice WRLD or Lil Peep—and I’m not just saying that because I have a book about emo rap coming out. woods accomplishes something tender with his music; it’s replete with longing and pain but nonetheless opaque. Aging bug meat doused in an invisibility elixir. woods would probably balk at the idea that he’s an emo rapper, and while there’s a gulf between the sing-song wails of the 2010s SoundCloud era and woods’ caustic and skeptical sermons, I can’t shake the fact that woods expands the definition of emo with his gnashing tone.

Maps is masterful. A tracklist without humdrum moments. The emotional apex “Hangman” is a panic attack, a spiral, bipolar nightmare: “I don’t sleep / I hover outside myself… People paralyzed by the lies they tell theyselves to make it manageable.” In the canon of single-producer projects from woods, it follows his first full-length with Segal, Hiding Places from 2019, and picks up where 2017’s Known Unknowns left off—that is, woods produces a springtime record that sounds like falling into a den of hornets.

The softness of Known’s “Unstuck,” produced by Blockhead, challenged the idea woods was just an abstract and severe rapper with poignant bars. And this is where language fails me. Writing well about billy woods is near-impossible. The knotty and curious music he has released since the early 2000s has inspired a steady drip of pieces from journos of all types, but I can’t shake the feeling all of us writers, myself included, are just writing around billy woods’ true nature as the saddest man at the indie rap party. Or at least the most alienated.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about how nothing means anything, and I have to meet life on life’s terms. Stop swimming upstream. Be a salmon, or whatever my two therapists suggest every week. This seems to be the driving force behind my read of Maps. “I can’t quite grab the new me,” woods says on “Bad Dreams Are Only Dreams.” Images of fallen halos follow. woods uses this song to meet the moment of despair and break through it. When I write about billy woods, I am searching for meaning when I should be scuttling down to the bottom of a dank well. His music is meant to situate you in a liminal space, and perhaps nothing more.

When woods raps “If it’s any beef today, good day for a cease-fire” on “Houdini,” I think about the disappearing act of suffering. woods himself is a true magician by trade, an alchemist by vocation, and a thundering presence merely by chance. He is the pinnacle of rap’s ability to stretch and morph searing emotion into something unrecognizable. That is, until you find yourself up late at night after an unceremonious baseball game, thinking about what it means to think about woods. And you get up in the wee hours of the morning, or evening depending on your inclination, and type out your most true-to-life read of woods: don’t bother, just be.