We spoke with The Ohio Players’ drummer James “Diamond” Williams who explained to us, in great detail, how Ohio Players recorded their 1975 classic Honey.

The Ohio Players’ story begins in Dayton, Ohio in 1959. During this early period, they were known as the Ohio Untouchables and were the band for a Detroit-based vocal group called The Falcons.

The Falcons were signed to Lupine Records and featured two future soul superstars: Wilson Pickett and Eddie Floyd. For the next five years, the Ohio Untouchables’ original lineup included Bassist Marshall “Rock” Jones, trumpeter and trombonist Ralph “Pee Wee” Middlebrooks, saxophonist and guitarist Clarence “Satch” Satchell, drummer Cornelius Johnson, and lead vocalist and guitarist Robert Ward. After a physical confrontation between Jones and Ward, the group disbanded in 1964. Despite this setback, they replaced Ward with guitarist Leroy “Sugarfoot” Bonner and altered their musical style and approach.

A year later, the group renamed themselves the Ohio Players. To increase the group’s prospects, they recruited saxophonist Andrew Noland and drummer Greg Webster, as well as two more singers — Bobby Lee Fears and Dutch Robinson. By 1967, they became the house band for the New York City-based Compass Records.

In 1968, the group released their debut single, “Trespassin’,” but left Compass Records shortly thereafter due to the label’s financial issues. The group landed on their feet when they signed new record deal with Capitol Records in 1969. They released their first album, Observations in Time, with little fanfare. With Fears and Robinson leaving to pursue solo careers, the group parted ways and found themselves retreating back to Dayton, Ohio. While spending time in Dayton, they were able to reform their group by adding keyboardist, vocalist, and songwriter Walter “Junie” Morrison, trombonist Marvin Pierce, vocalist Charles Allen, and trumpeter Bruce Napier in 1970. Their new lineup cut their first single, “Pain,” for Detroit-based Westbound Records. It became the group’s first top 40 hit. Within the next three years, they produced four albums, Pain (1971), the gold-selling Pleasure (1972) — which featured their first number-one single: “Funky Worm” — Ecstasy (1973), and Climax (1974). (Another notable feature from these albums was the presence of bald-headed model Pat “Running Bear” Evans on the cover.)

By 1974, the group underwent another set of changes; new members were inserted into the recording lineup, and they left Westbound Records for Mercury Records. New arrivals keyboardist Billy Beck and drummer James “Diamond” Williams became mainstays in the group. During this juncture, the group experienced numerous successes, releasing two consecutive platinum-selling albums, Skin Tight and Fire, in 1974. Around this time, Leroy “Sugarfoot” Bonner forged a dynamic songwriting relationship with Billy Beck and James “Diamond” Williams that would prove fruitful in coming years. The interplay of Bonner’s unique vocal techniques and Williams’ falsetto, along with the stellar musical arrangements, became the bedrock of the Ohio Players’ sound.

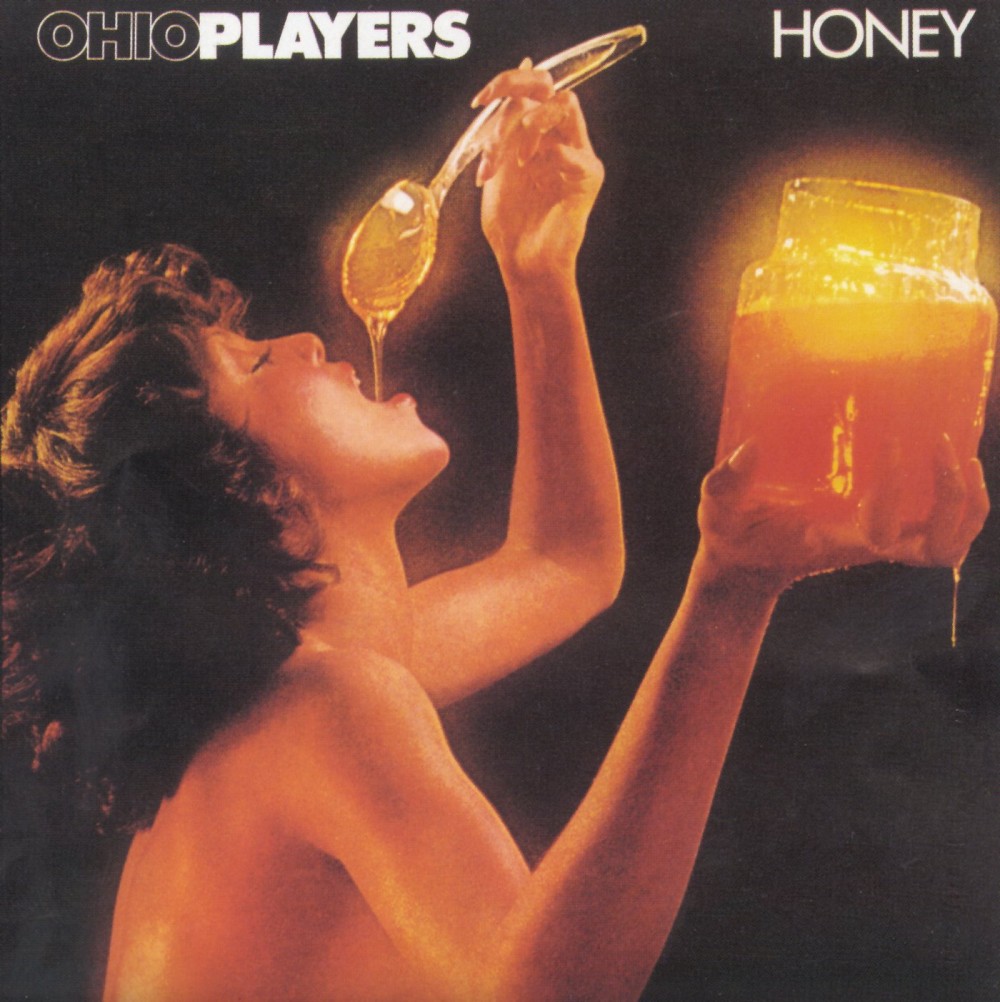

These triumphs laid the groundwork for their next album. On August 16, 1975, Honey would be released by Mercury Records, and it became the collective’s third consecutive platinum-selling album. The record would spawn three singles, including two number-one hits “Sweet Sticky Thing,” “Love Rollercoaster,” and “Fopp.” The album’s iconic cover featured Ester Cordet, a Playboy Playmate of the Month for October 1974. She was draped in honey from head to toe. Her presence made this album a memorable one among fans and historians alike. Crucial to the album and the songs successes was James “Diamond” Williams, who was a classically trained musician. At the time, Williams had been in the group for almost three years. Prior to joining the Ohio Players, he spent years playing in bands, most notably Overnight Low which became the group known as Sun.

For Honey’s 45th anniversary, we spoke with album architect Williams, who explained to us, in great detail, on how Ohio Players recorded this timeless classic.

What is the story behind you joining the Ohio Players?

I was in a band that was called the Overnight Low, a local band that played with the big bands in Dayton, Ohio, including the Ohio Players. One night, we were all hyped up thinking we’re going to get the better of the Ohio Players. It was all healthy competition. When they came off the stage, they had washed us like we were swashbucklers on a ship. They just wiped us out with the big mops [laughs]. That night, I told my girlfriend — she is my wife now for 52 years — “They beat us tonight.” But I was watching their drummer. He was playing the same tempo all night. I told her, “If I ever get a chance to play with their band, I was going to take his job.”

About four or five years later, in September of 1972, one of the guys in the band named Marvin Pierce called me and told me Greg Webster, who was the leader and drummer of the band, had taken sick. They wanted to know if I could fill in for him that weekend. That was the beginning of the story. The guys, Leroy “Sugarfoot” Bonner, Clarence “Satch” Satchell, and Marshall “Rock” Jones, went to the hospital with Greg Webster and told him he was not coming back in the band. He was fired immediately. I got the job. He went to be with the band that I was with, Overnight Low, which turned into a group called Sun.

Coming into the making of Honey, your band had a stellar year with recording two albums, Skin Tight and Fire, in 1974. What was your mindset as a group coming into the making of this album?

At that time, our band had the Skin Tight album. It went gold then platinum. Then, we put Fire out later that year and that did a little bit more. More than anything else, we were trying to keep up with the times. At that time, the other artists that were out there were amazing. It was just an amazing period of time in music. People were writing all kinds of wonderful songs. The musicality of the songs were just excellent. The melodies, harmonies, and everything was just at a masterful level. It was just about keeping up with the times. We were doing something, I think, no band had done at that time by managing to write three platinum albums in a row. We were successful at doing that. Our collective mindset had a lot to do with what was going on at that particular time.

You’ve mentioned all the groups and bands who were putting out high-quality material in the mid-’70s. Being in the midst of all that healthy competition, is that something that drove you all to make your records as great as they were?

What drove us was individual talent and the capability that started way before any of us started to record. Billy Beck was an expert playing the strings and keyboards. He went to music school, so he had that music structure. Sugarfoot was just an ingenious person, an unbelievable talent. He was just a unique kind of guy with his words and his concepts. The very talented Marshall Jones played bass. He was another unique guy. I also had 12 years of private lessons. I played with the orchestra band and all that stuff. I had music scholarships to go to colleges. During one summer, I got a full scholarship to Kentucky State University before I came out and got with this band. So there was a lot of music concepts in this band. We were just ready for the times, but we were prepared musically. All those classes and everybody in the band, even the horn players, Ralph “Pee Wee” Middlebrooks and Marvin “Merv” Pierce, made this band uniquely what it was.

When you began working on Honey, what was your band’s typical studio routine?

We were jamming for nine to ten hours. We would get to the studio around 7:00 PM and work in there until 5:00 or 6:00 AM. During this time in Chicago, especially in the winter at Paragon Studios, we would never see the sun. It was always dark. It was dark when we went in to record and it was dark when we came home. Sometimes, we would crash there and go and eat dinner and go over the music we recorded the night before and get ready to go back to work again. That was the pattern. Normally, we would go in there and book a certain period of time.

When you were working in Paragon Studios, how were things set up for the band to be able to maximize your output and sound quality?

They had the drum booth in there. Billy Beck would set his keyboards up. Sugarfoot had his guitar and an amp, and all that stuff, of course. We had the mics set up a certain way so there would be no bleeding in the mics we were recording into. There were mics in the room that were recording direct into the board like keyboards, guitars, and bass most of the time. Although, sometimes, they would mic an instrument and get that mic coming off the script. I was in the drum booth and all my stuff was soundproofed in there. When we were laying out the rhythm part and the rhythm track, it was not necessary for us to see a person or to be able to see. We just wanted to be able to hear when somebody said, “Cut it. That’s enough,” or when someone like Billy [Beck] might call a break and change a sound or Sugarfoot [Bonner] might say something. We wanted to have an open mic, so we could hear people and what we were playing that we vibed with. We wanted to hear what was coming out of our headphones, so we would be able to hear, in some cases, the click track, but also the bass guitar and the other parts. If a record is going to be good, it is based on its foundation, just like a house. When someone lays down the foundation of a house, and if it’s built well, anything that you put on top of it is OK. It’s all about that foundation in music, too. So it wasn’t as much about the placement as it was about what the guys were playing that made the sound important.

How did you all record your vocals for these songs?

We would record the music track, and then maybe with some additions to the rhythm track, Billy would start to do the vocals after that. The vocals weren’t being done at the same time. They were done independently.

Since the vocals were done independently, how much time did it take for you all to come up with the music and then cutting the vocals?

We were kind of Johnny-on-the-spot and Quick Draw McGraw kind of guys, you know what I’m sayin’? And that came from practice. It didn’t take us long. Once we came up with a concept or a thought, we could pretty much do our thing after that. When we were coming up with topics, we were influenced by what was going on around us, what we saw, and the things that we were feeling. In some cases, we just wanted to be different from everyone else.

Who usually came up with the harmonies and melodies for the songs? Was that a group effort?

Yes. There were basically three people. It was Sugarfoot, Billy Beck, and myself. We wrote, arranged, and then orchestrated. Most of the stuff was Billy Beck. Now, other people had ideas. Satch was great with coming up with titles and certain things that we would write around musically. Marshall, of course, played bass guitar, and he was instrumental when we would develop certain grooves, patterns, and stuff like that because the bass and the drums is where the groove really comes from in Black music. At that time, funk music came from the bottom. That’s where you feel what’s going on and how to shake what you’re going to shake and move what you’re going to move. Otherwise, all the candy, all the dressing, all the horns, the harmonies, background parts, second guitar parts, third guitar parts, and string parts, Billy, Sugarfoot, and myself would arrange all that stuff on the album.

What was your recording process during the making of this album?

At that time, we did things differently from anybody else. A lot of people in the industry always recorded their vocals first. I’ve been told that by a few engineers. We would write our vocals last. I guess that’s because we were musicians first. A lot of people are not. We were a band, so we came at it from a band’s perspective, in terms of our construction. The easiest thing for us to do was to play the grooves. We were not a singing group first, but we understood, back when the doo-woppers were doing their thing, they were taking all the ladies home [laughs]. So, we had to sing and play.

Before the Ohio Players, New Birth, and a lot of other bands, the music industry had all doo-woppers. The bands were in the background. We played for the doo-woppers, and they would take all the ladies home with them. They had suits on and doing dance steps. Some of them would be singing off-key and looking at us like we made the mistake and it was them. This is when bands figured they would have to start singing and playing. This didn’t apply to the Ohio Players because they had already progressed into that situation.

Here is a little bit of information: It was always difficult for us, to a point, to sing the parts when we had to play and sing them together because we had never done that together while writing the song. There was never a time when I started to sing, “You just go from man to man” while I was playing “Sweet Sticky Thing.” There was never a time that I sang that line. When it came time for me to sing it and play it, it was something. It was like, “This is crazy.” I hadn’t done that together at any time. It was kind of an ordeal for us to put that back together.

What was involved with getting the music recorded onto two-inch tape?

This was a process where we laid certain basic rhythm parts down of the four instruments: the keyboards, guitar, bass, and drums. We laid that down to where everybody was playing what they needed to play. Leaving spaces where necessary or making the changes properly and the notation being totally correct. One additive to the formula of the band that was absolutely wonderful was our engineer. His name was Barry Mraz. Barry Mraz was an ex-drummer that had excellent ears. His forte was mixing and mastering and knowing all about the gadgets that were going on at that particular time. But, because he was a drummer, I found a great partner with his ability to hear things. He showed me a lot and instructed me in a lot of ways that I was not aware of in the mixing process. Because of Barry, we had an engineer that was quite capable of making a true sound or the sound that we wanted to get out of the drums, guitars, keyboards, and vocals. It made a huge difference. We produced everything, so we were the boss and we’d go in the studio and spend time adding things that we thought were important.

So we’d put the rhythm track down, listen to the rhythm track, and after listening to the rhythm track, there would be certain holes and space after we put our overdubs on, which meant adding another keyboard part, putting on the strings, or putting on another part and guitar, then the hand part and another rhythm to the guitar that we had and percussion. Basically, at the end, we could feel where the intro should go, where the verses should go, and the hook should go. When we had that musically done, then we began laying down the hook. The hook is the thing that is repetitive within a song like “Skin Tight” or “Love Rollercoaster.”

We would lay down the hook, so we could get a certain vibe on what the hook was, to see how important that melody line was for the song. Then, we would go back and do our horn parts or other parts and lay down the lead vocals last. After that, we would add some other things like percussion, wind chimes, sound effects, or whatever that made the track have a feel to it and it clicked.

That’s intricate. As a band, how often did you all practice?

We practiced every day. Did you hear me say every day? Every day. We practiced every day. We took off on the weekends but every day we practiced.

It would be at least three or four hours. This was our job. You know what I mean? As I mentioned, the practice was for the purpose of being able to put together those vocals and things. We had to make sure everything sounded effortless. When I first began playing “Sweet Sticky Thing” and singing the vocals, my drum part was just like a vocal. I had never done it together. We had to practice because we did not want to fumble around when it came time to record.

In the studio, what was your band’s collaboration process like?

It was at a high level. It was intellectually stimulating. It was all business. Out of all the music that’s been played and produced in the world, you still hear the Ohio Players which is just unbelievable to me. It only came from the fact that we were serious about what we were doing. If we had been in the studio playing around and lollygagging and doing other things, I don’t think that you would have the music that you hear today. We were in there dedicated to the premise of making good music. Not just R&B songs, not just booty-shaking music, but all kinds of music.

Earlier you mentioned the song “Sweet Sticky Thing.” How did it come together?

After we came up with the arrangement for the song. Marshall played the bass part. For the guys that could sing and play, Sugarfoot, Billy Beck, Chet [Willis], and myself — we put together the arrangement of the song. Once everybody was suitable and happy with it, we recorded it.

Where did you get the idea for the song “Love Rollercoaster?”

We were flying these twin-turbo engine planes. They were called Navajos. They were fighter planes. They had twin-turbos, two engines on the planes. We went through heavy turbulence, where we were dropping around 200, 300 feet at the time. I used to always sit and co-pilot. A few of us took some lessons flying planes. This plane was just dropping in the sky. We were having turbulence because of a storm. Somebody said, “This ride is like being on a rollercoaster.” Under no other circumstance would I have ever thought that I would’ve been dropping out of the sky in one of these planes, but it was for the love of making music and the business. I said, “This is a love rollercoaster here.” Then we just turned it into a song.

One of the most famous parts of this record is the vinyl sleeve of the Playboy model dripped in honey. Who came up with that idea?

From our Westbound record collection, the Ohio Players were notorious for using adoring women on our album covers. When we went to Mercury, The Playboy studio was there and a guy named Bill Laswell. Satch would collaborate and come up with names and concepts for certain albums. The Playboy studio photographer came up with a concept. We approved the concept. Then, we would go finish the album or whatever. They’d take the pictures of whoever they had on the cover. This was a collaborative thing. Most of the models were Playboy models that we used in Chicago.

Being full-on musicians, did you all write out sheet music for these songs?

We had people do that for us. Well, Billy Beck could write out the sheet music and conduct the score for it. I could write out parts and the parts that I played, but I did not write out all the parts that we played on the album. Sugarfoot couldn’t read music but he was one of the most talented musicians I’ve ever heard. His lyrical and melodic ability was just exceptional.

How did “Fopp” evolve when you all were creating it in the studio?

The song, “Fopp,” was basically a rock-and-roll song. It’s like heavy metal. We would go off in a different direction musically more so than any other band at that time. It wasn’t an R&B or pop song. At that time, our idea of writing a pop song was “Love Rollercoaster.” “Love Rollercoaster” was a pop song. It went to number one on the pop charts. It was not an R&B or funk song. We wanted to write a pop song, so we wrote a pop song. Likewise, that’s how we would write songs. The concept of “Fopp” was toward that direction. A lot of bands like Soundgarden and Red Hot Chili Peppers covered this song. Obviously, it tickled their fancy.

How did “Ain’t Giving up No Ground” materialize? It’s just under two minutes.

Yes. It was just a groove. It was just a groove at the end of the night. The groove was good. We just made a little vocal part to it because the groove was hot. It wasn’t long enough to make a song, but it was about attitude. That’s what it was about.

Who came up with the idea for the song “Let’s Do It?”

Sugarfoot came up with a lot of our lyrics because, as I mentioned before, the boy was just exceptional. A lot of the lyrics, especially the lead vocals and some of the hooks, came from him. The concept of the song was let’s love. We had the track that we had written, and Sugarfoot, Beck, and me sat down and came up with words and phrases. We were thinking of different ways we could say let’s love and hope. It just worked out with the music. Then, we would work out harmonies for something we wanted to sing on the verses. It is a love song and one of our fan favorites.

What about the making of “Alone?”

Everybody feels alone sometimes. It is a heck of a feeling. Musically, we tried again to come up with a concept that fit the title. It’s a sad song. The Ohio Players had other songs like that on their older albums. One of the songs they recorded when they were on Westbound Records was “Our Love Has Died.” It came out and they just buried it. The group was big on using concepts and sound effects. It was a great song.

As you look back, how does it make you feel that your group is still respected and revered?

It’s all been a joyful ride. If I could look back on the years and do anything different, I don’t know that I would. Nonetheless, it’s been absolutely wonderful. There’s no one thing that sticks out no more than the other. People ask me, “What song is your favorite?” All of my babies are my favorites. I love them all or no one would have ever heard them. They’re all my favorites. We’ve been very blessed to be around a long time in this industry. We’ve gone places and done unbelievable things. One day, we were blessed to be with Stevie Wonder and hang out with him when we were recording our album, Fire. I’ve been at Aretha Franklin’s house for her holiday party. My daughter was hanging out with her kids on Christmas and stuff like that. I’ve been so blessed in my life. It has been unbelievable.

__

Chris Williams is a Virginia-based writer whose work has appeared in The Guardian, The Atlantic, The Huffington Post, Red Bull Music Academy, EBONY, and Wax Poetics. Follow the latest and greatest from him on Twitter @iamchriswms.