On September 28, 1976, Stevie Wonder’s masterpiece Songs in the Key of Life was released. We spoke with members of Wonderlove and legendary engineer Gary Adante (Olazabal) about how this timeless album was made.

One hundred and four minutes and twenty-nine seconds of artistic brilliance captured the minds of a generation.

Coming off winning back-to-back Grammy awards for Album of the Year in 1974 and 1975 for Innervisions and Fulfillingness’ First Finale, the mass hysteria surrounding Stevie Wonder’s next studio effort was at an all-time high. For most of 1974 and the whole of 1975, Wonder began recording his eighteenth album while on the road, performing concerts and in various studios. Around the same time, he found new members: drummer Raymond Pounds, bassist Nathan Watts, trumpeter Raymond Maldonado, saxophonist Hank Redd, guitarist Ben Bridges, and keyboardist Greg Phillinganes to fill vacant slots in his newly revised Wonderlove band. The only holdovers from previous versions of Wonderlove were guitarist Michael Sembello and vocalists Deniece Williams and Shirley Brewer.

By late 1975, Wonder was seriously considering leaving the music business altogether. He expressed his disdain with the way the United States was conducting its affairs in Ghana. As a result, he made a conscious decision to emigrate to Ghana to begin working with handicapped children and other humanitarian efforts. A farewell concert tour was in the works until he decided to resume his recording career by signing the most lucrative contract for an artist during that time. His record deal was reportedly worth up to $37 million while maintaining full artistic control over his music.

Despite these sets of important changes, the decision to abandon the fruitful four-year partnership he developed with producing and engineering tandem Robert Margouleff and Malcolm Cecil proved to be impactful. He elevated the assistant engineer role of Gary Olazabal to become his main engineer and paired him with veteran engineer and owner of Crystal Sound Studios, John Fischbach. The album had 130 different contributors and the infusion of youth helped to keep the creative juices flowing throughout the recording process. Together, Wonder and his Wonderlove band held legendary recording sessions at Crystal Sound Studios, The Record Plant and The Hit Factory Studios. The original release date for the album was on Halloween of 1975, but Wonder felt the album needed more fine tuning.

After going back to the drawing board, Wonder finally decided on a title for the double album. The original title was Let’s See Life the Way It Is, but he settled on Songs in the Key of Life because he yearned for the album’s content to represent the key of life and its indefinite success. Due to the insatiable craving for new music from Wonder, Motown seized the opportunity to capitalize on the public’s fervent desire by selling “We’re Almost Finished” T-Shirts. The culmination of an almost three-year musical journey came to fruition when the album was released in early autumn of 1976.

On September 28, 1976, Songs in the Key of Life was released by Tamla Records, a subsidiary of Motown Records. The twenty-one-song offering became Wonder’s magnum opus as a recording artist. At 26-years-old, he was at the peak of his creative powers. The album spawned two chart-topping singles, “I Wish” and “Sir Duke” and two other singles, “Another Star” and “As.” Upon its release, it landed atop of the Billboard Charts, became the second highest-selling album through 1977, and sold more than 10 million copies. In an effort to celebrate the album’s 45th anniversary, we spoke with three legendary members of Wonderlove: Raymond Pounds, Nathan Watts, and Michael Sembello, and legendary engineer Gary Adante (Olazabal), who provided an epic account into the making of this timeless album.

When did you first meet Stevie Wonder and start working with him?

Michael Sembello: I just happened to be in the right place at the time thanks to a friend of mine. He woke me up one Sunday morning and told me that this guy named Stevie Wonder was looking for a musician. Back in the late 1960s and early 1970s, I really didn’t know who he was, but I heard about him. I was into John Coltrane and a bunch of jazz stuff back then. I asked my friend, “Is it that blind guy?” He replied, “Yes, that is him.” My friend told me to come with him because he really wanted the gig. So, I went there with no knowledge of who Stevie Wonder was or his music. Fortunately, for me, this was when Stevie started to move into his jazz phase. When I showed up to the tryouts, there were a couple of hundred different musicians waiting in line. They all had Stevie Wonder’s music and his books with them while they were sitting down. It was kind of like a game show.

I remember one of the guys saying, “What song are we going to play Steve?” Everyone started flipping through their Stevie Wonder song books. Stevie replied, “Man, just follow me.” And that was the beginning of him playing Coltrane stuff. I started to play and by the end of the audition, I was in pretty strong standing and quite perplexed because I really didn’t know what I was getting myself into. At the end of the 1960s, there was still this whole segregation thing between the whites and Blacks. Most Motown bands didn’t have more than one white player in their band. [Stevie] already had a white trumpet player and there was an argument going on in the corner of the studio. Ira Tucker, who was the publicist, told Stevie, “Look, you don’t realize you hired a White guy.” So, Stevie motioned me to come over to him, and he said, “Hey, man. What’s your sign?” I didn’t know what he meant, so I thought he was asking me what my nationality was so I answered him, “I’m Italian.” Stevie turned around and said, “Guys, he’s Italian. He’s not white. He’s in the band.” [laughs]

Nathan Watts: When I first played with Steve, I didn’t audition. I came from Detroit, where I went from playing in front of 35 people a night to playing in front of 250,000 people for a concert for Jesse Jackson. I got a call on a Tuesday saying that Steve wanted to check me out and to learn as much of his albums as I could. I had only been playing two years, and I was young. I was playing something called a National bass. A National bass is a short-scaled bass guitar that you could get from a store called Montgomery Ward. It was a really cheap bass. I came in and went backstage after one of his shows. He was surprised when I started playing “I Was Made to Love Her.” It was the first song I learned from a cousin of mine who was from the South. We proceeded to go through a few more songs, and at the end they said, “You sounded great.” Stevie began to play the song “Contusion,” and I never heard of the song before. I went over by him and watched his left hand carefully. Every time he hit a certain note, I would hit the same note on my guitar. Then, he made a transition in the song and from there I was lost. But when I got the gig, we went back into the studio and we got it together.

Gary Adante: I remember setting up mics, chairs, and everything for the horns on “Superstition.” It was just one of the last things for Talking Book, but I was not really working with him yet. It was part of a session that the studio was having, so I was assigned to that. I think I was 19 or 20. I was an assistant engineer at Record Plant for a few years in Los Angeles. I assisted on a number of big albums. We had three main studios, and they were pretty packed with real big stars of the time recording what became a lot of classic rock-type music. I was assisting Stevie’s engineers [Robert Margouleff and Malcolm Cecil] on his sessions that were pretty much working around the clock in the Innervisions days.

Raymond Pounds: Stevie was looking for a new young drummer. [Trumpeter] Hugh Masekela asked Stix Hooper, the drummer from the Crusaders, and he recommended me. I went over to Stevie’s house to audition. Someone had to pick me up and then drive me up to the house because it was up in the hills and you’d never find it. His bass player, Reggie McBride, took me up there. Stevie came out and unlocked the gate. I said to myself, “I don’t know if this guy is really blind.” So, we got out of the car, and he said, “If you don’t play good, we’re going to kick your ass.”

We went in and started playing some of his songs. I knew a lot of them. I was a big fan. When I got there, he was crazy about the way I played, and I was crazy about him. He began to call me every day to come to his house to play with him all day. It was the three of us, me, the bass player, and Stevie. We spent three weeks rehearsing at his house. Then, we went to a rehearsal studio to continue playing together. After a couple of days, Reggie McBride quit. Stevie just had that car accident, and he hadn’t been doing any music because he was recuperating from the car accident that almost took his life. Everybody in the band was gone. He was putting his band back together. I started coming up to his house every day, and we would rehearse all day. He would write songs. I didn’t realize what a genius was until I watched him write three, four, or five new songs every day.

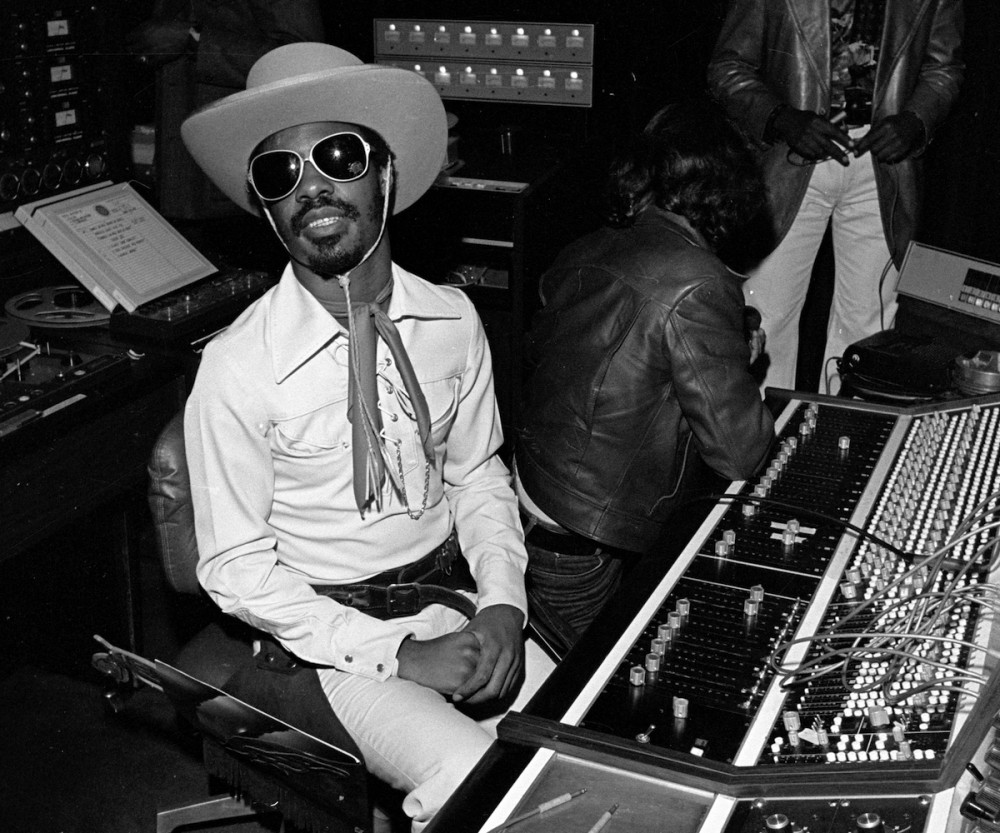

At 26-years-old, Stevie Wonder was at the peak of his creative powers. Songs in the Key of Life spawned two chart-topping singles, “I Wish” and “Sir Duke” and two other singles, “Another Star” and “As.” Photo Credit: Richard E. Aaron/Redferns

Since you were there towards the end of the making of Fulfillingness’ First Finale and at the beginning of this album, Raymond, what was involved in recreating the Wonderlove band?

When I first got with the band, it was just the great Reggie McBride. He was from the old version of Wonderlove. The following week, we flew Michael Sembello, the guitar player, in from Philly. After I had been with Stevie for a few weeks, Reggie McBride quit. He went with Rare Earth. They gave him more money. We had to find a bass player. Oh, God, we must have gone through 15 bass players in Los Angeles. They would come in, and Stevie would call one of his tunes. The cat would play a song and then Steve would teach him something to see how fast he could learn. We went through that process with all those guys and nobody was satisfactory. We needed to find a second guitar player, get the background singers back, and we had to get an extra keyboard player. We had a bunch of auditions to choose different players in the band. Stevie knew whether or not it was a yes or no. He didn’t have to hear you do much. After several auditions, Stevie hired guitarist David Myles, saxophonist Hank Redd, trumpeter Michael Fugate, keyboardist Michael Stanton, and background singer Susaye Greene. Shirley Brewer and Deniece Williams came back during the same time.

This new version of Wonderlove rehearsed together for six weeks, and we went on tour across the United States to promote the Fulfillingness’ First Finale album. We toured from April to December 1974. We were going to do our first concert. It was in Atlanta and it was with Jesse Jackson for his Rainbow Coalition. We didn’t have a bass player, and Steve asked Ray Parker Jr., “Do you know a bass player? I need a bass player, man. I auditioned all these cats. I don’t like none of them.” Ray Parker Jr. replied, “Call this guy named Nathan Watts.” Nathan Watts was one of the most incredible bass players ever. When he joined the band, he had only been playing two years. They flew Nate to Atlanta. He met us in Atlanta.

The last concert we did was at Madison Square Garden in New York City. We decided to take a Christmas break. Then, in January 1975, we went to Hawaii and Japan. We stayed in Japan for 3 weeks. When we got home, Stevie fired Michael Stanton, David Myles, and Michael Fugate from Wonderlove. This is when Greg Phillinganes, Ben Bridges, and Ray Maldonado came into the picture and joined the band.

When did you all begin working on this particular album?

We were working on Songs in the Key of Life as soon as I got in the band and didn’t realize it until the album was done. He was always writing songs. After the second week I became his drummer, he called me on the phone and said, “I want you to come to the studio. I’m in the studio.” I went to a studio called the Record Plant in Los Angeles. When I got to the studio, he was playing the drums on a song. He’s a great drummer, man. He played the drums on all his albums. He doesn’t even let the drummers play on his album. Most of the bass he also plays. When I went up to the studio, he was recording. Then, I started going to the studio with him. Some of the songs he would develop there, like “Isn’t She Lovely.” We recorded a few songs that was sort of like that song, and I realized later, a couple of songs that he wrote were parts of “Isn’t She Lovely.” He would say, “Oh, I take that from that, and I make this song out of it.” He was always recording. Once I started with his band, he was recording all the time.

What was the chemistry like between Wonderlove and Stevie Wonder during the making of this album?

The band Wonderlove rehearsed Monday through Friday. We rehearsed from 10:00 AM until 5:00 PM. Sometimes Stevie would say, “You guys come to the studio.” I went every night. I was going to the studio to watch Stevie Wonder work. I ain’t have nothing better to do. Plus, if you wanted to play on a song, you had to hang around. He’d create a song and I’d say, “Hey, Stevie, can I play on this one?” Sometimes, he would say yes. Most times, he’d say, “No. I’m going to play on it because I know exactly what I want.” There was 21 songs on this album. I’m only on three. I had to beg because we were recording for three and a half years before that album was finished. Every time he would write a song, we would record it and finish it. I played on a lot of songs. Then, we’d come to the studio the next night and he’d go, “Check this out. I wrote this song. It’s going to replace so and so.” All these good songs I’m playing on, and they kept getting bumped off the album.

Every now and then, he would call me. If I wasn’t at the studio, and he wanted me to play on something, he would call me. Even at 1:00 AM, he’d wake me up and say, “Come down to the studio. I want you to play on a song.” If I didn’t get there fast enough, like one time, when he was working on “Another Star,” I got to the studio, and he was walking out of the big studio all sweaty. I said, “Oh shit. He’s done playing drums already on it. I’m too late.” At that moment I said to myself, “You know what? I’m going to start making sure I come every night when he’s creating songs, so I can get on some of these songs.”

We wrote songs together too. Wonderlove were three girls and seven musicians, a horn player, a saxophonist, and a trumpeter. What we could do during Wonderlove rehearsal time was write songs together, or we could write individual songs. It was a great situation because if you had a song, you could bring it into rehearsal and get Wonderlove to perform your song. You could choose which one of the girls you wanted to sing lead on your song, or you could sing it yourself. Stevie would bring songs and give them to Wonderlove, and he would teach us the song and we would learn and perform his song. We used to open for him on our tour. The girls never sang with us while we’re in the studio. Most of the time, the rhythm section, the horns and the singers, they would come in and put their parts on later. The bass, drums, and guitars would lay down the track for the foundation of the song, and then they would bring the horns. Stevie would make up the horn parts, and they would put the horns on there. The place where we rehearsed every day was blocked out. Our rehearsal studio was blocked out for three years. Our equipment was in the studio. Everybody knew we were in there. Earth, Wind & Fire would come and rehearse one album, record the album and put it out and then go on the road on tour, and they did that with three albums while we were still recording this album. [laughs]

Nathan Watts: Everything on the album happened organically in the studio for the simple fact that we rehearsed a lot of material with Stevie while we were on the road touring. Most of these songs we rehearsed with him before we recorded them in the studio. This is where his production skills came into play. He would decide if he wanted a 4-part band to play on the song, or if he was going to play the instruments on the song. He carried copies of the songs that we rehearsed with him, and he would listen and decide what direction he wanted to go in for a particular song. We were all young and in awe of him because he was the master. We all went to the same school of learning how to write and produce songs by watching him. It was a benefit for all parties involved. He had tools that were unblemished, and we were willing to work hard to make him happy. And we had a tool that we could learn from.

Can you take me through the recording process while you all were in the studio together?

Back then, the recording was done in all analog. It was a lot of fun to be around there. There would always be food and things around. We would always take breaks and go out to dinner somewhere as a group. One good thing about Steve was he was big on having a family atmosphere around him. We would have our share of arguments, but we would get over them quick. So, we would get to the studio each day, and we would get there on time. We would do our jobs, then go grab something to eat and come back and work on the next song. We learned so much as musicians about the technology and what it took to know about engineering and the sound of a record. We used to call it “The Wonder School.” We got an education on what it took to become a success in music.

Gary Adante: We tried to make it spontaneous, so we would record everything multitrack. If Stevie was writing, he would just sit at the piano for hours and all these amazing songs would just come one after another with melodies. We’d always have to keep at least a 2-track recording going constantly to capture any of all of that stuff, in case he wanted to go back and remember something that he’d written and start a real album song from that.

View of the cover of the album ‘Songs in the Key of Life’ by Stevie Wonder, 1976. Published by Motown Records (T13-34062), the album’s jacket features a drawing of Wonder’s face set inside a series of nested, ragged circles. Photo Credit: Blank Archives/Getty Images

Gary, during the three-year period of making this album, you all recorded in four different studios. What were some of the differences in size and sound quality?

Well, Record Plant rooms at that point were pretty much designed by [studio designer] Tom Hidley. They had horn speakers, and they tried to have their rooms be somewhat compatible. As far as Crystal Sound was concerned, we didn’t sit in between the two large, main monitors on the console. It wasn’t asymmetrical, so we were off to one side. That was odd and interesting to get used to, but whatever it did, it worked. Crystal had a big control room. A lot of people could and did sit all around while we were working. There was a pretty big record room, but it wasn’t very live sounding. We could get it to sound more live, but all the recording from the ‘70s was pretty dead. It was just the style of the time. In order to attract clients, they were just looking for that. One, it was easier to contain all of the leakage. The other thing was the sound. It was a style. At Hit Factory, we recorded at night. Steely Dan was in during the day, so we did the same thing. We were just passing the reception area with them. It was a small control room that we used mostly.

Gary, how important was it developing synergy with John Fischbach and Stevie Wonder?

It was important because we had to like each other. I remember we went to Jamaica to Bob Marley’s studio to record backgrounds on a song that was never released off of Songs in the Key of Life. Physically and technically it wasn’t great. Stevie wasn’t happy with the background singers, and we also went there for this one session, but ended up spending two or three weeks in Jamaica, just because it was Stevie. It was a significant experience in my life that taught me a lot, especially about patience.

When Wonderlove were in the studio, did you all record them as a full band or one person at a time?

It just depended on the song or the situation. Sometimes, when Stevie thought that a string bass sound suited a song better, he would have Nate [Watts] play it. Sometimes, it was him and Nate playing with it. Then, either Stevie would play the drums, or he’d bring in somebody who was playing drums at that time or a studio drummer. Stevie’s drumming style was so distinctive, and he was really good at it. He heard what he wanted done, so he didn’t have to explain to somebody the parts or anything or style. It was, I guess, more efficient to do it himself.

Gary, was the drum set up in a way that made it easier for Stevie to play them?

Not really. It was set up conventionally. That’s how he learned when he was a kid. He knew basic distances. He did destroy microphones from hitting them with the sticks. He also played a lot of times, just to get the sound with the butt end of the stick using that end instead of the tip. That’s why there was a lot of hi-hat on a lot of songs because he hit the crap out of the hi-hat cymbals and played them as hard as he would hit the snare. Unlike a senior musician who is schooled in the delicacy of going from hitting a hi-hat to whacking a snare. Stevie hit everything just as hard which sounded great. It’s his style and it’s very distinctive. Everyone can hear a record and tell that’s him playing drums.

Raymond, who were some of the other noteworthy people who stopped by the studio while the album was being made?

Raymond Pounds: He was in Crystal Sound every night. Very rarely would he work in the day, but sometimes he would. The studio was blocked out and everybody heard that Stevie Wonder was working on his album, so everybody came there. Berry Gordy dropped by to see what was going on, Diana Ross, Carole King, Andy Williams, Alex Haley, Donna Summer, and Rick James used to come by before he got hits. Rick was a determined guy who acted like a star before he was a star. He used to come by the studio in a limousine, because at that time, in Los Angeles, somebody could rent a limousine for $25 an hour with a five-hour minimum. He did that three or four times and then later Rick James got a hit. [laughs]

At that time, did you all receive any type of pressure from the record label to hurry up and finish the album?

Michael Sembello: He was basically under the pressure of the corporate machine at that time. The record company was saying they needed another song like “Superstition.” It made us start to wonder who were we making these records for, and we started to question our whole existence. He had reached this point before the start of this album. I think the fact that he hired a band with me, Nathan Watts, Raymond Pounds, and Greg Phillinganes helped him. He hired a band that had this unquestionable passion for music. With everyone feeding off of each other, it helped to create this record. It made a big difference with him moving on with the music. He still had the chance to be creative, but he was also surrounded by the energy from a group of young guys. We were all new kids on the block. I honestly didn’t know who Stevie Wonder was then. All I knew was that he was great, and I wanted to play with him. I think through us, he was able to get out of that questioning phase and back into making music. I guess the universe put the right musicians in front of him to inspire him.

Steve used to take a long-time doing things because he was on his own flow. He would get to the studio, and we would be there waiting for him. He was like a musical vampire. He could stay up for three and four days at a time. It was a long, long process of everyone trying to keep the inspiration going and that’s hard to do when there were a bunch of executives coming in every few days asking you questions. The people who had the money to pay for the process were horrendous back then. They were saying, “We don’t hear a Superstition type of record in that bunch.” They almost made him seem like he was some type of a jingle writer. People don’t realize that’s what’s behind every great artist is putting up with the incompetent people who are paying for everything. Essentially, it was great that we were altogether because it was meant to be.

Gary Adante: Of course, there were a lot of visits from the Motown brass at the time. Stevie’s attorney would corner John [Fischbach] and I and try to hurry things along. My response was always like, “I can’t sing. I can only put up the microphone, and when he gets here, I’ll record it, but I can’t hurry this process because I’m not the artist. I can only make it as easy, simple and expedient as I can.” Motown took the credit, but I made the t-shirts that said, “We’re Almost Finished.” Then, I made ones later that said, “Let’s Mix Contusion Again.” I was just doing it because I thought it’d be funny. I would make them for me, John [Fischbach], and the assistant engineer. Motown thought it would be a good marketing tool. I think they made a few thousand “We’re Almost Finished” t-shirts to get people interested in it. We got a lot of pressure, but that went along with my whole career with Stevie.

“He’s a great drummer, man,” Raymond Pounds said. “He played the drums on all his albums. He doesn’t even let the drummers play on his album.” Photo Credit: Chris Walter/WireImage

Let’s go in-depth into the making of some of the songs from this album.

“Love’s in Need of Love Today”

Raymond Pounds: “Love’s in Need of Love Today” was the last song we recorded, but the first song on the album. I was with him when he recorded that song. I guess he must have had the idea in his head and everything because nobody had heard it. I hadn’t heard it. I went to the studio as usual at night around 9:00 PM. Sometimes, you’d be waiting on him, and he didn’t come in there till he’s ready. So, I was waiting. Then, when I got tired of hanging around and tried to leave I’d say, “Hey, Stevie, I’ll see you tomorrow. I’m getting ready to split,” He’d respond, “No, no, hey, don’t leave, hang.”

It was 1:00 AM when he started to record “Love’s in Need of Love Today.” First, he’d get the piano part, and he’d sang a little rough vocal while he played the piano. Then, after he did the piano part, he did the synthesizer keyboard bass part. I was sitting there, and I was the only one. Everybody else was gone. By the time he did the piano part and he did the bass part it was 3:30 AM. After that, it was time for the drum and I said, “Hey, Steve. Man, can I play on this one?” [laughs] He said, “No, I’m going to play this one because I know exactly what I want.” He was right. He did the drum part and then he did all those voices. He did all those like in four or five parts.

Gary Adante: I know that when we were doing “Love’s in Need of Love Today,” Stevie sent Alice Kim to do the vocals. Usually, he’d stand up but there were so many layers for that song. I think he just felt more comfortable sitting down due to that length of time. Also, I remember [singer] Jackie Wilson fell on stage and collapsed right before we did the vocal a few days before. He was in the hospital. Stevie was really super emotional because he thought that Jackie wasn’t going to come out of it. I think he eventually did. He lived for a few years after that. Stevie would sing a line or so, and we had to stop recording and turn off the mic several times just to get through it because he would just get overemotional and couldn’t carry on. I will always remember that. It was so much, it wasn’t anxiety, it was just hard to witness. That’s the sort of thing you don’t forget. He kept saying, “I’ve gotten all these Grammys, I’ve gotten all these accolades, and Jackie Wilson never got any of that.” He felt like it was this guy, who was obviously somebody that Stevie looked up to and emulated possibly, that never received the respect that he deserved.

Nathan Watts: On “Village Ghetto Land,” Stevie played all of the instruments. Many people didn’t realize that there were no strings on the song. They were actually synthesizing the strings from a Yamaha keyboard he had in the studio. During the early ’70s, he acquired one of these keyboards when they first came out. The way they made the strings sound on that record was incredible.

“Contusion”

Michael Sembello: On “Contusion,” we were rehearsing right across the hall from John Mclaughlin and Chick Corea. We all used to hang out as musicians back then. Stevie was influenced by everything. We would sit around and listen to different jazz artists. I think the song “Contusion” came out from the type of stuff Chick Corea was doing. He wanted to express the fact that he could play and that he wasn’t just this pretty voice. Everything on that record would be an A&R guy’s nightmare today. [laughs]

“Sir Duke”

Raymond Pounds: For “Sir Duke,” he wrote that shortly after Duke Ellington passed away. He got the inspiration to write “Sir Duke” for Duke Ellington. One day, Wonderlove was at rehearsal and we rehearsed from t0:00 AM that morning until 5:00 PM. At 5:00 PM, we could go home or we could go get dinner and go to the studio where Stevie was and stay there all night. What happened was, he came to our rehearsal at a quarter of five, and we’re getting ready to wrap it up for the day. He came in, and when he showed up, you couldn’t leave. He said, “You know I got a song. I wrote a song. It’s for Duke Ellington. Come on, I will teach it to you.” He taught me the drum part, he taught Nathan [Watts] the bass part, he taught the guitar player, and taught everyone their parts. It took us about 45 minutes to learn that song. After that, he said, “OK, let’s go to studio and record it.” Well, it was 5:30 PM. We’d been there since 10:00 AM morning. I said, “Look here, man. I’m hungry. Let us go get some food. Let us eat, and then let’s come back at 7:00 PM. OK?” He replied, “OK.” That was it. We went to the Sizzler and had some dinner. We went to the studio at a quarter of seven and started recording “Sir Duke.” We played it once or twice, and then they turned on the red light to record, and we recorded that song.

Michael Sembello: On “Sir Duke,” we would basically sleep at the studio most of the time. I remember falling asleep in the vocal booth, and I knew I had to do my guitar part in the song. I would wake up every few minutes and ask, “Is it time yet?” They would tell me no. Two days went by and it was like 6:00 AM and Steve said, “It’s time!” There I was sitting in the booth next to a Marshall amplifier with headphones on and half awake waiting to play my complicated guitar part. The reason I was able to do it was due in part to everyone being so energized and fueled to do the music. It was an incredible experience and it made me realize that I could play while being half asleep. To see the excitement from Stevie Wonder, you can’t help but become energized. When you were in the same room with him your IQ went up by 50 points.

“I Wish”

Nathan Watts: “I Wish” was a song that he never rehearsed. He wrote the song in one day. I was there with him the whole day, and we did nothing that day. I was there until 1 o’clock in the morning, and I told Steve that I was leaving because I was tired. He told me to go ahead and head home. He called me back at 3:30 in the morning and told me to come back to the studio. He said, “I got a song and it’s going to be good. You gotta hear it, and you have to play on it.” The next thing I know I was back at the studio, and we came up the song style and that was it. We came up with the bass line, and he was playing on the keyboard, then I embellished from what I was hearing from him. I finished up my part at 5 o’clock in the morning and went back home. He did the horns and the backgrounds the next two days and it took about 3 to 4 days to complete the entire song.

Gary Adante: “Pastime Paradise” was interesting because of the chanting and the choir. Stevie had suggested that we have people chanting with finger symbols, so I went up to the Self-Realization Fellowship Temple on Sunset Blvd in Hollywood and spoke to them. I asked them if they would be interested in being on Stevie’s album. They agreed that they would come in and chant, sing, and play their cymbals on the album. They all walked single file. I don’t know how many miles, but they walked all the way from where the Shrine is to Crystal Sound. There were so many of them, maybe 50 people. We didn’t know what to do in the record room. They sat there, just went on and chanted for hours until Stevie showed up. One time he didn’t show up, so I had to apologize, and they did it again and this time Stevie actually showed up.

“Isn’t She Lovely”

On “Isn’t She Lovely,” it was one of the things that we had to get the timing just right. Because there weren’t enough tracks of his daughter, Aisha, I think it was just a 16 multi-track to lay that down on a single track. We left it on a two-track and then every time we had to get it in exactly at the right time. I do remember that being a pain in the neck. The recording of her crying was in their home in New York, I think. It was her mother’s recording. She was on the audio as well.

Raymond Pounds: Stevie had this song, “If It’s Magic.” There was no piano. There was just the harp and him singing. He said, “I’m going to call up Alice Coltrane and have her play on “If It’s Magic.” She came with her harp. If he was going to do something with somebody, he would call me and say, “Come to the studio. I want you to see what’s going on.” When I got there, Stevie had an idea. He was the producer, so he was putting the album together. When a producer has a concept in his or her head, you need to do what they want you to do. He kept trying to tell her how he wanted her to play and she said, “Well, this is the way I hear it. This is what I feel.” See, if he called you in to perform on his record and it was not working out, he won’t argue with you and say, “I’m the producer. You need to do this.” He’d just say, “OK.” He let her play, and then he told her, “Great. Thank you.” Then, I said, “Stevie, there’s this harp player, and she’s a Black woman. Her name is Dorothy Ashby. She’ll play what you want her to play.” I brought Dorothy Ashby to him. And the rest is history.

“As”

Michael Sembello: Herbie Hancock came into the studio to play on “As.” He was one of the many people that came by the studio during the recording of the album. I got to meet a lot of people that I really admired. It was just a party of musicians there and everyone wanted to be involved with the album. Greg Phillinganes had just joined the band, and he was the kid of the group. He was 18 at the time, and I was a little older. Herbie’s album had come out a couple of weeks prior, and Greg hopped on the keyboards and starting playing some songs from the album. Herbie had this look on his face, and he was impressed. It was like we all died and went to music heaven during the whole process of making the album. It was young people mixed with veterans that had a mutual respect for one another. There was just a lot of joy there and Steve really attracted that.

Nathan Watts: I was just a young boy walking into the studio and there was Steve and the wizard working on “As.” I didn’t even know how to act. There were the two greatest piano players who have ever lived. Herbie Hancock, are you kidding me? I walked in there, and then we began playing, and we hit it off from that point forward. Herbie was sitting down at the piano playing in the key of B. Anyone who plays an instrument knows how difficult it is to play in the key of B. Herbie walked through it like it was day and night. I was sitting there in awe. Michael Sembello was in there with us. I remember calling back to my friends in Detroit telling them I just finished playing with Herbie Hancock.

“Saturn”

Michael Sembello: It’s funny how the song “Saturn” came about. He asked me if I had any ideas for this song he was working on. He gave me this tape, and he was saying something about going back to Saginaw. I asked him what he was actually saying. He told me, “The song is called “Going Back to Saginaw,” but that’s not going to work.” I said to him, “Yeah, that doesn’t sound very exciting.” Later on that night, I told him the first thing I heard when I listened to the lyrics again was “Going Back To Saturn” and he said, “Yep, that’s it! Go finish it!” He told me to come back the next day, so we could record the song. I thought to myself what would it be like to be a disgruntled alien that came to this planet to try and do good and help people, and we ended up running him away with our guns and bibles in our hands. So, he sang I’m going back to Saturn. I didn’t think it would ever make it on the album because the record company hated it so much. Thank God for double albums, because if it was a single album, it would have never made it.”

Steve’s metaphors are really double entendres and “All Day Sucker” was another one of those. A lot of times it was us playing music spontaneously and the groove from a live band will become a song. Essentially, he had the groove and the next thing we know we have a song. We didn’t have names for the songs at that time.

Gary Adante: “All Day Sucker” was interesting putting a guitar on it because I went to Frank Zappa, who I had a relationship with, because I had worked with him on a few things. I liked Frank, and we tried it. He was amazing, but it was one punch that he couldn’t replay what was on the track. It just really wasn’t as great as we’d hoped it to be. My friend’s nephew, WG “Snuffy” Walden, had met Stevie because he would come to the studio to see him. Stevie asked, “Why don’t you call your friend and see if he’d be willing to come down?” It was past midnight into the wee hours of the morning. He came down and was full of energy and played guitar on that. I think he did a great job.

“Easy Goin’ Evening (My Mama’s Call)”

Nathan Watts: The first recording that I used an upright bass was on “Easy Goin’ Evening (My Mama’s Call)”. It was the first time I had played the upright bass guitar at all. I taught myself how to play the instrument, and I had only been playing the guitar for two years when I met up with Stevie to do this album. Steve gave me some grace on that record because I had a good ear, and I could pick up things quickly. But I was having trouble at first then once I felt my way through it, I was good. I used a lot of open strings on the record and most upright bass players use open strings on a record.

As you look back 45 years later, what are your feelings about being involved with one of the greatest albums ever made in the history of music?

Michael Sembello: When I listen back to the record today, I realize that I was just learning how to play. Steve was one of my greatest teachers when I worked with him. I’m just starting to comprehend the record, because when you’re in the process of doing something, you don’t know the magnitude of it. When I go on the internet and I go to YouTube, I type in my name and Steve’s I see young kids competing with each other by playing our song “Contusion.” It’s like Wow! I begin to realize I was a part of something great here and left something for the next generation. The energy from the record is going to live on forever and ever.

Nathan Watts: It changed the focus of all musicians. The whole album had variety. It wasn’t stuck in one genre. It wasn’t just an R&B album. It had Latin influences and there were many facets to it. “Pastime Paradise” was a song that had religious overtones, “Isn’t She Lovely” was a song for his daughter, “Joy Inside My Tears” was a soulful, emotional song. There were different songs that touched on many different subjects. A lot of the material done on the album was magical and a once-and-a-lifetime type of thing. It sold millions of copies and is in the top ten of all-time albums in music history. It will stay that way forever. It is timeless. I was lucky to be a part of it. I was just a young man from Detroit.

Raymond Pounds: I never thought that I’d be his drummer and that I might get a chance to play on one of his songs or some of his songs. He didn’t need me to play. Stevie was the best man at my wedding, and he paid for my honeymoon. I picked him up and helped him put on his tuxedo and drove him to the church, so I could get married. We’ve been such great friends for so many years. It was a great experience being a part of this album, man. It was my first big job with Stevie Wonder as a drummer. It changed my life.

Gary Adante: I think when you’re actually doing the work, you don’t think about what kind of impact the music will have on listeners’ lives. You’re just working to capture the sound and the experience clearly and maybe putting a digital thumbprint on it, so people realize that you had something to do with it. You can imagine how cool it is to get somebody, especially if they don’t know you got anything to do with it, who starts talking about that album as being like, “Oh, that was my favorite album.” I live in the Seattle area. I met a keyboard player and one of the songs was his wedding song that he and his wife marched down the aisle to. I thought, “Holy shit.” It’s still having an impact on people’s lives now. It’s a great feeling that something you did had some sort of legacy to it.

__

Banner Photo: Gijsbert Hanekroot/Redferns

Chris Williams is a Virginia-based writer whose work has appeared in The Guardian, The Atlantic, The Huffington Post, Red Bull Music Academy, EBONY, and Wax Poetics. Follow the latest and greatest from him on Twitter @iamchriswms.