Photo by Adam Bhala Lough

Adam Bhala Lough is an acclaimed filmmaker. His cinematic efforts have appeared numerous times at Sundance, he’s been nominated for a Spirit Award for his writing, and “Filmmaker Magazine” named him one of the “Top 25 Independent Filmmakers To Watch.” Lough specializes in making music films that prove to be deeply candid portraits of his subjects, like his controversial 2009 documentary on Lil Wayne, The Carter, and his appropriately kaleidoscopic biopic The Upsetter: The Life and Music of Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry. He started his career behind the camera, however, as a hip-hop-obsessed college student making videos for one of the most innovative, enigmatic MCs to ever touch the rap game, MF DOOM. Here, he describes in intimate detail his eye-opening adventures capturing the mercurial DOOM on celluloid during the rapper’s ‘90s-era prime, at the height of the era’s underground hip-hop revolution.

This article was originally written for FRANK 151 Magazine.

In the late ‘90s, independent hip-hop had reached its plateau, and I was a backpack-rap fanatic. I had just moved to New York City from Virginia, and religiously attended every show from Company Flow to J-Zone. I trolled around Fatbeats, drooling over costly import vinyl I knew I’d never buy (except the Bobby Digital Japanese version, which I dropped $40 on); I even waited in the cold for an hour to shake hands with De La Soul. But it was in the fall of 1999 that I attended the most important show of my life, one that would change the path of my filmmaking career: MF DOOM at the Knitting Factory.

Born Daniel Dumile, the former Zev Love X of KMD, was performing songs from Operation: Doomsday on a bill with Atmosphere. Wearing a mask and appearing on stage for one of his first shows since ending a five-year sabbatical that followed the death of his brother, fellow KMD member Subroc, DOOM‘s performance was magnificent. His legendary partner MF GRIMM showed up in a wheelchair to watch from the balcony. Chuck D and his new rock band, Concentration Camp, were headlining, but everyone was there to see DOOM. There was a feeling in the room that we were all witnessing something special, something unique and mysterious. In fact, after DOOM got off stage, the entire crowd left, and Chuck seemed pissed.

It was at this particular show that I met a man named “DJ Fisher,” who professed to manage DOOM‘s career. DJ Fisher and I talked about the opportunity of making a music video for one of DOOM‘s songs. I told him I would do it for free because I had access to camera equipment and discounted film stock through NYU, where I was studying. He liked that idea, and responded well to my passion and positive energy. I didn’t just want to direct a video for the hell of it: I wanted to direct a video because I was so completely moved by DOOM‘s performance, and the mysterious aura around him.

There was something incredibly bizarre about him. He was far too individual to follow the day’s expected rap trends. Instead, he was a 30-something, overweight, prematurely balding, Golden Age-era rapper in sweatpants and a silver WWF wrestling mask. Onstage, DOOM stalked back and forth, spitting out incredibly abstract lyrics over Sade samples. He referenced Jeopardy Daily Doubles, shouting out ancient comic book characters, and revealded that he wrote his masterpiece album from a prison cell (BCDC-O Section, Cell #17, up under the top bunk).

Courtesy of Adam Bhala Lough

Later that night, I went back to my East Village apartment and drank a couple 40s with my homeboy Mike Konrad. I remember we blasted Operation: Doomsday so loud that the upstairs neighbor came down to complain. A great night. Over the course of the next month, I wrote a couple of video treatments for DOOM; the first was for “Red & Gold,” which I proposed filming a beatdown in slow motion. I also wrote a treatment for “Hey!” that would have featured DOOM portraying a “normal guy,” playing various characters like a janitor and a deli worker. The general concept was that he was an MC who also works a normal job (something I realized years later when I read Ta-Nehisi Coates’ New Yorker piece on DOOM, he actually did in the years before Operation: Doomsday was released).

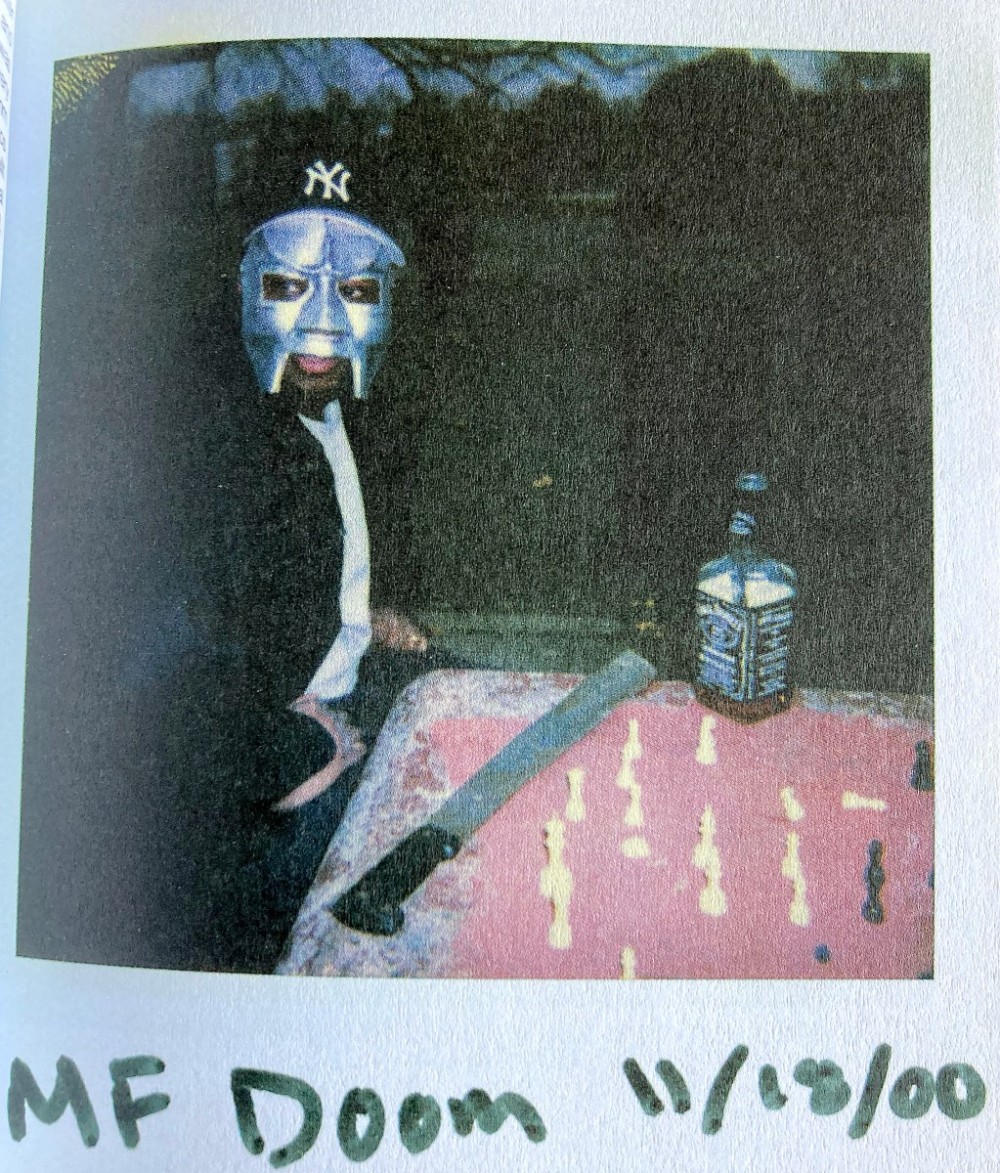

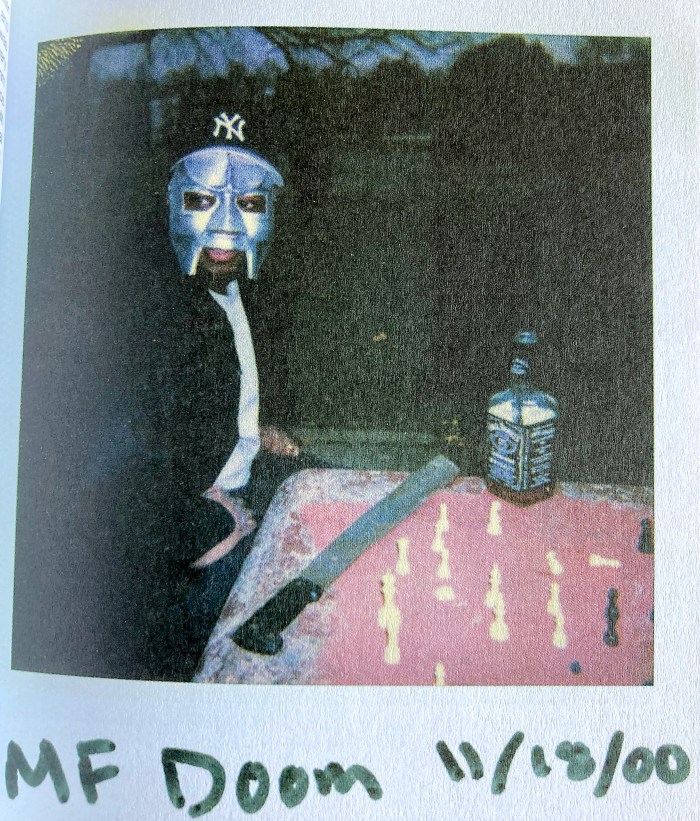

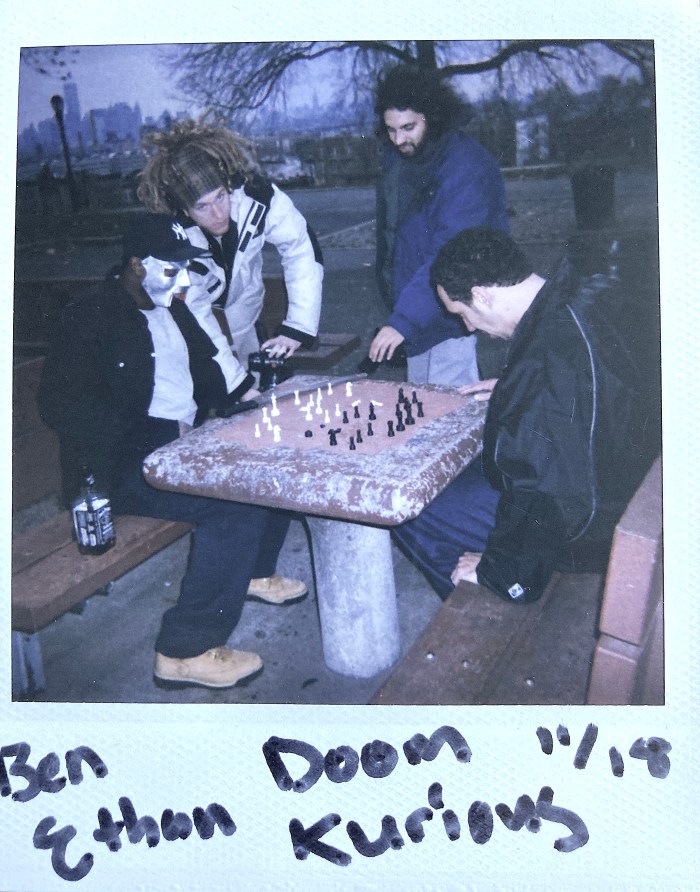

Naturally, DOOM rejected both ideas. He wanted to do a video for ’?,’ the penultimate song on Operation: Doomsday, co-starring his friend, the rapper Kurious; I was pretty excited about that option, as I’d get to work with not just one but two great artists. I suggested we do a real basic video set in a Brooklyn park, depicting DOOM and Kurious just hanging out and passing time, playing chess, sitting on benches, drinking some beers. That was the idea: keep it simple. DOOM liked that approach, and said he’d be coming up to New York in a few weeks, as he lived in Atlanta at the time.

Back then, I was paying $600 a month to share a apartment with two friends on 13th Street and 3rd Avenue. My bedroom was tiny: 8 x 10 with no closet – probably the same size as the jail cell in which DOOM wrote the album. I was a film student at NYU, which was quite a scene at that particular moment in history. Karen O from the Yeah Yeah Yeahs was in my “Experimental Film” class; one of the kids from TV on the Radio worked at the edit room checkout counter. And week after week, sitting in class next to me was Ben Rekhi, the Northern Cali-bred filmmaker who would go on to produce Bomb the System, my first feature film as a director.

The cinematographer on both DOOM videos, Ben was on a career path to shoot film for a living. Over the summer, he’d interned with the illustrious Roger Deakins, the great shooter for the Coen Brothers. Ben was very comfortable with the ARRI-S, the 16mm camera we shot both MF DOOM videos on. In fact, he moved around like a maniac with that thing on his shoulder. The ARRI-S is an old camera, originally invented for documentary work. It is not crystal sync, so you cannot shoot sync sound with it, but it shoots slow motion and has three different fixed lenses – all good attributes for shooting a low budget, documentary-style music video.

We decided to shoot the video in Sunset Park, in order to take advantage of our friend Ethan Higbee’s apartment as crew headquarters. Ethan was also in our film class, though he never showed up: he spent more time painting in Brooklyn and hanging out with a beautiful European girl who happened to be roommates with a British-Arab girl I was madly in love with. Ethan allowed us to set up in his apartment and store our equipment there. The night before the shoot, Ben and I went out to Sunset Park to scout the location; it took us so long to get out there, however, that the sun had already set. As we returned home, I got a call from DOOM: he asked that I buy a liter of Jack Daniels for the shoot. I went to the liquor store and bought a bottle; that night, I drank a quarter of it with my friend Perez. I fell asleep late and nervous, and woke up very early on day one of the shoot.

Operation: Doomsday was originally released in a small quantity on Bobbito’s personal record label, Fondle ‘Em Records. When I had initially met with DOOM about the videos, that was the label with which he was associated. But a mere few weeks before we shot the videos, DOOM sold Operation: Doomsday to a small upstart label called SubVerse Records, owned by the former Company Flow MC Bigg Jus and a white dude that looked like he worked for Morgan Stanley. Call time was 7:00 AM, but by the time DOOM finally picked me up in his wife’s car, it was already mid-day. I was freaked out that the sun was going to set on us, but DOOM made me take him to Foot Locker on 14th Street and buy him a new pair of Timbs and an outfit.

Assured by DOOM that SubVerse would pay me back, I put it on my credit card. SubVerse did eventually reimburse me when I delivered them the finished video, but I think they did it more out of the goodness of their hearts, not because it was in DOOM‘s contract. They saw how broke I was: at that moment, I was living off my parents and working part-time at a minimum-wage NYU work-study job. I could barely afford the $100 Timbs, but DOOM would not shoot the video unless I bought them for him. I realized right then I’d been hustled.

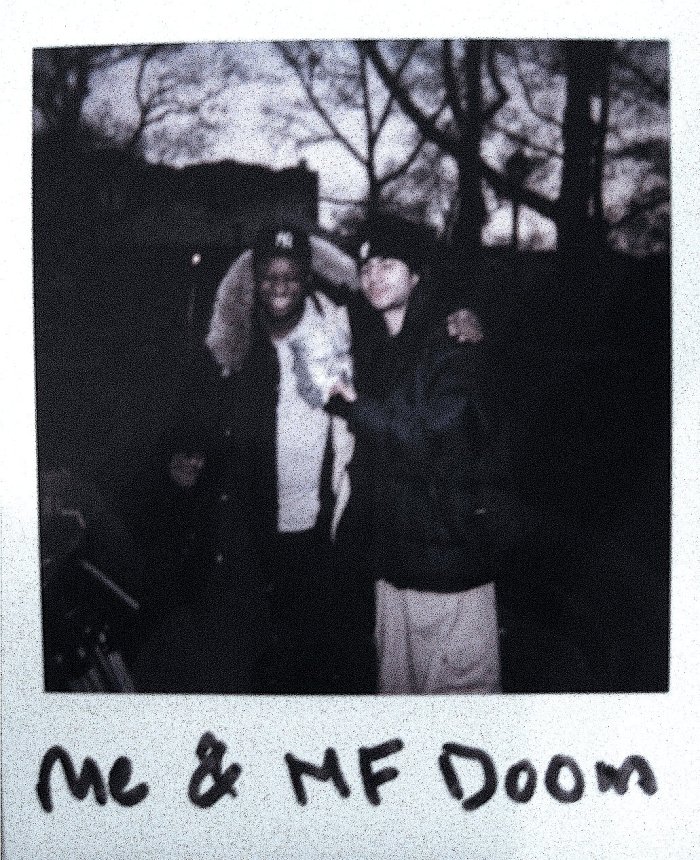

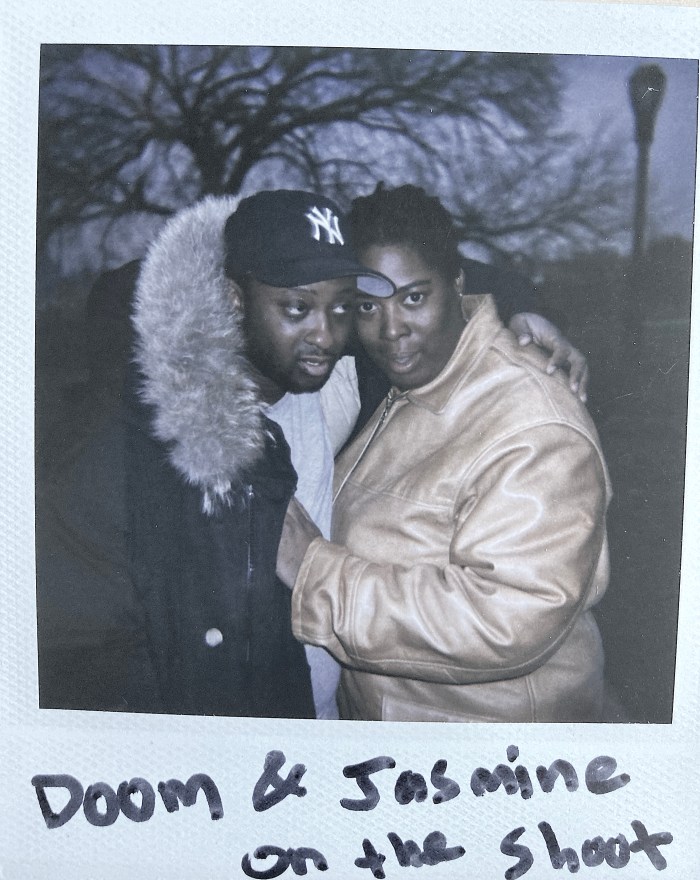

Timbs procured, we headed out to Brooklyn. While stuck in traffic, I chatted a little with DOOM‘s wife, Jasmine. She was a sweet, genuine, good-natured woman whom I remember fondly; she made me feel very secure, and helped ease some of my nervousness. I remember looking at DOOM‘s CD collection in the car; it was one of the biggest, most impressive collections of hip-hop I’ve ever seen. We finally arrived at Ethan’s apartment a good six hours past call time. Ben and Ethan were both waiting when we arrived; they would serve as my crew for the entire shoot. Kurious was there, too, and he and DOOM went to work on the Jack Daniels immediately. DOOM drank heavily that entire weekend. The previous time I’d hung out with him, he was drinking a Budweiser in a brown bag with a straw while conducting an interview at SubVerse Records’ office with a white reporter from some music magazine.

Photo by Adam Bhala Lough

For the first shot, Kurious and a friend he’d brought along who claimed to be an up-and-coming MC sat on Ethan’s stoop drinking while DOOM stood in front of the camera, rapping directly into the lens while wearing his plastic “Doctor Doom” mask. Meant to represent Doctor Doom of Fantastic Four fame, he actually used a WWF Kane mask purchased from Toys “R” Us. Years later, DOOM would get a proper mask made, but that day the Toys “R” Us job had to do; it had actually been spray-painted silver by the famous graffiti writer KEO. KEO – aka the pioneering white rapper Lord Scotch, aka Scotch 79th aka Blake Lethem – would become a close friend of mine, and play a pivotal role in my first feature Bomb the System. There were rumors that DOOM was homeless at one point; I’m not sure as to the validity of these rumors, but what is true is that DOOM slept on KEO‘s sofa for a year or so. Those guys were inseparable, but eventually fell out over bullshit money issues (as many, many people did with the SuperVillain). KEO and DOOM later made up and KEO was one of the last people to see DOOM alive in an undisclosed location where he had sequestered himself before his death.

As the day wore on and DOOM got progressively drunker, we moved into the park. Kurious did not want us to shoot him playing chess with DOOM: he felt it was too “Wu-Tang-like,” and worried he’d be accused of biting. I thought that was ridiculous, and we shot it anyways. In retrospect, Kurious was right: it was a complete bite of a shot in Wu’s clip for “Da Mystery of Chessboxin.’” But to me, that was okay because that was a video that had come out when I was thirteen years old; I was paying homage to an image from my childhood.

By the time we got to the chess sequence, DOOM had gotten pretty drunk, and the drunker he got, the quieter and gentler he became. As the day wore on, it got colder and colder, and soon the sun was setting. Kurious, DOOM‘s wife, and our entire crew had all left, but DOOM didn’t seem to mind; every shot was okay with him, and he trusted me to make it good. Kurious came across to me as the opposite: he didn’t seem to respect me at all and sized me, Ben, and Ethan up immediately as a bunch of corny, film-school pothead amateurs, which probably wasn’t far from the truth. Luckily, we shot Kurious’ verse twice; in the middle of a shot, he disappeared without even saying a word to anyone. I never saw him again.

Late in the day, Ben and I shot DOOM rapping into the camera with the Twin Towers directly behind him, silhouetted in the twilight. Those buildings would appear in two music videos I made that year; one year later, they would fall to the ground. I would videotape their destruction from the roof of my girlfriend’s apartment in downtown Manhattan; I’ve never looked at that MiniDV tape again. After we wrapped, we reconvened at Ethan’s apartment and hung out for an hour or so with DOOM, Jasmine, and what was left of the crew. After we smoked some herb, DOOM started to head home. On his way out the door, we realized his new Timbs were missing; it turned out Kurious had walked off with them.

Photo by Adam Bhala Lough

The next day we would shoot the second location for the video: the infamous 205 1st Avenue – a classic East Village, late ‘90s apartment. I lived there for one year in 1999, and my dynasty passed the apartment on to Ben and his clan. It had a huge terrace that was perfect for massive house parties, and an open door policy. It was the type of apartment where you could do anything you wanted: if you needed a place to shoot a scene, that was your spot – no one cared, and everyone creative was invited in. People would stop by at all hours of the day and night just to hang out and freestyle to instrumental rap beats or drink 40’s and smoke weed without hassle. Ben, Ethan and I would shoot a public-access television show called Public Sex Acts in the apartment every week, with our roommates Sebastian Demian (now Lil B’s manager) and Jesse Nicely (the former managing editor of Frank151 magazine, who originally commissioned this piece for the MF DOOM issue). “Public Sex Acts” would be the launching pad for our DOOM videos – the place where they received their world premiere.

The morning of the second shoot day, I took the subway up to the Kodak store across the street from the old Madison Square Garden post office to buy more film. On the subway, I was listening to Operation: Doomsday on my Discman when I was struck by a new concept for a video for the song “Dead Bent.” This song has no chorus, consisting of only one verse rapped over a repetitive Isaac Hayes sample. My idea was to shoot a video that had no edits – just one shot, in the same way that the song was one uninterrupted verse. DOOM would spit the verse while walking from the apartment in 205 down to the deli in front, where he’d steal some fruit and run off, all the while holding a mic in his hand. Then I came up with another idea: I’d shoot the scene twice, once forwards and once backwards, and put them together in a single split screen. We shot the first side of the split screen in black and white and the other in color. There was no real reason for these choices; I just did it for the sake of experimentation – I was making these videos for my “Experimental Film” class, after all.

When I arrived at 205, Ben, Ethan and I began to set up for the day, waiting three or four hours for DOOM to show up. DJ Fisher notified me that DOOM was at a photo shoot for The Source and would get to us as soon as possible. Butterflies in my stomach, I walked down to the deli, bought a six-pack of beer, and started drinking. Eventually DOOM did show up, and I told him we had a slight change of plans. He thought my idea for the “Dead Bent” video was cool, though, and agreed to go ahead and shoot it right away.

The video begins with DOOM in the back bedroom (my old bedroom) with Jasmine. He steps out of the room in sweatpants and a bummy t-shirt, wearing the plastic DOOM mask. He walks into the living room, puts his Timbs on, moves outside onto the terrace where a million house parties popped off, then comes back inside, down the stairs to the deli, where he proceeds to take a basket and select pieces of fruit, all the while rapping to the camera. Eventually, he runs down the street with the basket. During one of the takes, the deli owner, who somehow thought there was really a man in a Toys “R” Us mask holding a microphone stealing a basket of fruit, chased DOOM down the street. We shot this particular take two or three times and then shot the reverse, beginning with him putting the fruit back in its proper place, walking back upstairs, onto the terrace, taking off his Timbs and being pulled back into the bedroom by Jasmine.

When we finished shooting the “Dead Bent” video, we moved on to shoot another verse for the song ”?.” This time, we decided to create a makeshift black box by draping a black sheet on the wall in 205 and placing DOOM in front of it, rapping to the camera. As we were shooting, we realized DOOM was rapping with a razor blade in his mouth. I asked him why he was doing that, and he responded that he often kept a razor blade under his tongue. I asked him to flip it up and down inside his mouth with his tongue, which we filmed in slow motion. Somewhere in between all of this, DOOM took his mask off and placed it on the couch; naturally, Ben sat on it, almost breaking it in half. DOOM was really pissed off about this – Jesse Nicely overheard him calling us “a bunch of amateurs” and griping to Jasmine about wanting to leave.

Needless to say, we did not shoot any more footage of DOOM. He went to find Kurious and retrieve the Timbs that Kurious had “borrowed” the day before. That would be the last time I saw DOOM for months, until he did a show at S.O.B.‘s and asked me to come and meet him after the show. I did, but during the show a strange, unsettling incident occurred. At one point, he was rapping on stage with Megalon. They began arguing mid-rap, dropping the microphones by their sides and yelling into each other’s faces. Soon, it looked like they were swinging on each other. Megalon suddenly ran off stage and out the front door, with DOOM chasing after him.

I ran outside, along with thirty other dudes expecting a fight, and saw DOOM running down Varick Street after Megalon. There were other people involved; all kinds of chaos ensued. The show was over; when I tried calling DOOM‘s cell phone, I wasn’t surprised when he didn’t pick up. I walked home with an unsettling feeling in my stomach. Who was the “real” Daniel Dumile, and what was really going on behind the scenes? Honestly, I didn’t want to know. As with many people I worked with over the next decade, I pretended the dark side didn’t exist, and validated it by the fact that we’re all artists, and artists are just complicated people.

I spent the next few months at the NYU editorial lab cutting the ”?” and “Dead Bent” videos. After I’d whittled the footage down to rough cuts, I sent the videos out to Atlanta so DOOM could give his feedback. I didn’t hear from him until that Christmas, when I was traveling in India, along with Ben and Jesse. Ben and I both had family in Bombay: Ben was staying in the ridiculously lavish Oberoi Trident hotel on the waterfront (a few years later this hotel would be one of the locations hit in the Mumbai terror attacks that killed 174 people), while I stayed with my aunt and uncle and two cousins in an apartment complex fifteen minutes away by foot. Every afternoon, I would walk over, passing the outdoor marketplaces steaming with Mumbai street food and a never-ending sea of beggars to check my email in the Oberoi’s upscale corporate lounge. One particular afternoon, I finally got word from DOOM. He had seen both videos. He didn’t have too much feedback, negative or positive, but he was concerned with a particular shot in the ”?” video in which the bald spot on the back of his head was visible. He wanted me to take this shot out. (I didn’t.) As well, he wanted me to change the skin color of Doctor Doom from white to black in the clip I stole from the original Fantastic Four cartoon. (I couldn’t.)

***

Upon returning from India, I mastered the videos on BETA SP tape, and handed two submasters over to SubVerse records; I also sent copies to DOOM, Kurious, and Bobbito. Bobbito had a private mailbox in the Mailboxes Etc. on 3rd Avenue in the East Village. DOOM had given me his address, instructing me to send copies to him, and I eagerly complied. I left an official letter with my phone number, asking Bobbito to call me after he saw the videos, but never expecting he actually would. A few weeks later I got a call: Bobbito said he saw both videos, and liked them, especially the ”?” video, especially the footage I had cut in from the original Fantastic Four cartoon. He wasn’t feeling the “Dead Bent” video as much, however, but said he had shown it to an artist friend of his, and she had responded very positively to it.

In the call, Bobbito invited me to come by his radio show the next night. I accepted his invitation, and less than 24 hours later I was on my way up to Harlem. Bobbito’s radio show had been built up so massively in my brain that I had all these visions of the station being this incredible hip-hop Mecca. On the subway ride up to Harlem, I imagined some ridiculously pimp studio with plush leather couches, a sick vocal booth with photos of all the hip-hop legends who’d passed through that place, signed and framed over every inch of wall space – a veritable shrine to hip-hop in the ‘90s. Exiting the subway, I walked a few blocks through Harlem proper until I reached a church. In the basement of the church, I traversed a long hallway into a claustrophobic back area, where the walls were lined with rows and rows of bookshelves filled to capacity with records. Everything about the place was jazz – jazz posters, jazz album covers, overweight nerdy jazz DJs milling about; there was no hip-hop to be found. I wondered if I was in the right place.

Eventually, I made it to the barebones studio where Bobbito was already on the air. Later, I realized two things: 1) Bobbito shared the room with other DJs during the day, and 2) Bobbito didn’t get paid a dime for doing his show in all 12 years of it being on the air. To this day, I’m not sure how I overlooked these two important facts, but I guess I was just a naïve kid from Virginia. The studio was small, with a half-dozen mics lined up in front of a table. On the right side were some chairs and a sofa, where I sat about ten feet away from Bobbito as he and Lord Sear recorded the CM Famalam show. As I watched, I tried to be cool, tried to put on a vibe that I wasn’t a tourist and I actually fit in, which in retrospect was probably ridiculous. I was 20 years old, and my youth was a dead giveaway that I was not meant to be there. Or maybe I was?

Bobbito didn’t really speak to me until the end of the show. I finally approached him and said, “Hey, I did those DOOM videos”; he smiled, shook my hand, and that was it. Camp Lo was the guest that night. They rolled into the little room five or six deep, freestyled for a bit and talked up their new album. I watched from afar, quietly soaking in the experience. When the show ended, I slipped out unnoticed and took the train back down to the East Village. To this day, I’ve never seen Bobbito again.

Growing up in Virginia, I had been listening to Bobbito’s show for years through a series of cassette recordings of the show that my friend bought from a mail-order catalogue each month and generously passed around our high school. The week I moved to New York in 1997, the first thing I did was purchase a bunch of blank cassettes to record his show. Listening to the show in my dorm room in the Village, I wondered what unknown artist Bobbito was going to break next. Bobbito had put on so many MCs throughout the ‘90s: Biggie, Jay-Z, Nas, Big Pun, Mobb Deep, Wu-Tang Clan, DMX, Big L, Cam’ron, Pharoahe Monch and Company Flow had all gotten shine on that show when they were unsigned and relatively unknown. (There were even rumors Bob was the one who “discovered” Organized Konfusion after hearing their demo while working in Def Jam’s mailroom.)

In 1998, The Source voted it “Best Hip Hop Radio Show of All-Time.” The importance of the show was not lost on me, but falling asleep that night, I couldn’t help but feel my journey uptown was pretty anti-climactic. I didn’t even get a t-shirt. Twelve years later, though, I recognize the importance of that moment: I had the honor of bearing witness to one of the most important cultural institutions in American music history, and, at the young age of 20, worked with one of the greatest rap artists in history.

Throughout the four or five months working with him, DOOM came across to me as a genius, undoubtedly brilliant, slightly nerdy, but also dodgy, capricious, and an unapologetic hustler. He smiled a lot, laughed a lot, drank a lot, and was warm and open in social situations. He’d trust you with certain details from his life, yet not trust you by a damn sight with other things. There was a dangerous side to DOOM that lingered right under the surface, which came out when he told me stories about the meaning behind songs like “Red & Gold” (“Wig twisting season/Where some could get their wig twisted back within reason”) – a fact-based song about cold murder in the streets. Meanwhile, “The Mic,” is basically an explanation of how he ended up in prison. I’ll leave the Villain to explain that one.

We also spoke briefly about the death of DOOM‘s brother, Subroc. He brought a photo of Subroc holding a machete to the video shoot, insisting I put it in the video. At the time, I didn’t really think much of it other than it referenced another lyric in the song (“I still keep a flick of you with the machete sword in your hand/Everything is going according to plan, man”). In retrospect, however, I realize how much the photo meant to him, and how much the video must have meant to him, too. To say it meant a lot to me would be an understatement: it has been one of the highlights of my filmmaking career. I never got a chance to tell him, but his confidence in me gave me confidence in myself as a filmmaker to continue to pursue my dream of being a director, against all odds. A was a 20-year-old kid with no experience directing music videos. He had zero reason to give me a shot, but he saw something in me that I didn’t yet see in myself.

MF DOOM gave me my “big break” and I’ll forever be indebted to him for that. His always-creative wordplay, prolific nature, and self-reliant, DIY approach will forever inspire me.