Art by Evan Solano

Abe Beame is standing in line for a slice of the devil’s pie.

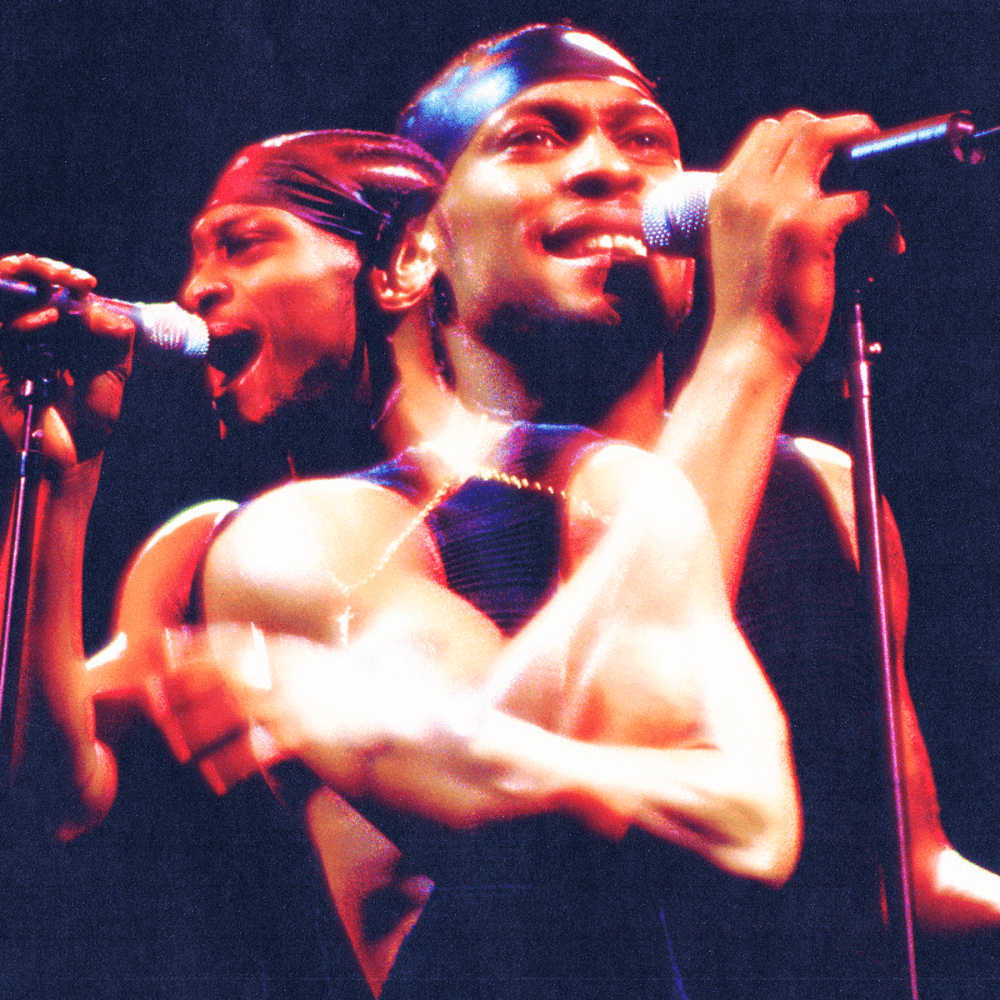

He had a government name, Michael Eugene Archer. But to the world, he was D’Angelo. One name, an idea, a symbol of sex and beauty, of the mercurial artistic temperament, of complete creative freedom and genius. The heir to Curtis Mayfield, Marvin Gaye, and Prince. But if the news is to be believed, D’Angelo has sung his last new song, performed live for the final time, and ascended to another astral plane. He supposedly died of pancreatic cancer. He was 51 years old.

In D’Angelo, we can chart the trajectory of soul music from approximately 1990 through 2015. He first emerged from South Richmond, Virginia as a member of Black Men United, a supergroup with one credited song to their name from the Jason’s Lyric soundtrack. “U Will Know” was a great R&B version of “We Are The World,” a politically conscious anti-violence song created by a kid who began singing in a Pentecostal church. It has the power of gospel and kind of fucks. It’s the work of a talented mimic who has complete command of his instrument, who could’ve been anyone he wanted to be in this industry: Wanya Morris, Usher, John Legend, insert conventional 90s-2020 R&B star here. The possibilities boggle the mind.

D’Angelo had the pen, the voice, the face, the talent. What’s remarkable is that he gets near top billing amongst a Justice League that includes Boyz II Men, Tevin Cambell, Mint Condition, Gerald Levert, and Tony Toni Tone, presumably because despite being a relative unknown, he wrote and produced the song and plays piano on it. In retrospect, it’s a passing of the baton, one generation confronted with the voice that will define the next.

Brown Sugar is similarly stamped by its moment: a perfect collection of ten jazz standards and original songs that sound like jazz standards. It came out of the moment just before neo-soul, where Bohemian hipsters sipped espresso at 11 p.m., while snapping in between performances to express their approval of slam poets and keyboard players. (For younger readers, Hollywood is always a bit late but if you want to see a facsimile of the scene check out Theodore Witcher’s Love Jones.) This was the parlance of Brown Sugar, but once again it was more profound, more profane, a little rougher around the edges. Edited versions of his tape may have been sold next to a Starbucks register but amongst this cohort of R&B singer songwriters, D’Angelo immediately stood out, demanded your attention, made you sit up and say shit, damn, etc.

What is there even left to say about Voodoo? Released 25 days into this century, it seems fairly clear that any “Greatest Album of the 21st Century” list will have an anti-climactic conclusion. It’s an impossible proposition on paper: An experimental R&B album that draws in equal measures from Motown and Hendrix and P-Funk and Native Tongues and produces a four-quadrant masterpiece that literally everyone likes. It throws out the pageboy cap and brown butter leather cool of D’Angelo’s debut and unleashes his falsetto, helps you understand his ancestry – that he actually always belonged in a bedazzled costume on stage with the Family Stone.

Voodoo is a transgressive world-changing bolt of lightning from the Gods that is somehow also the perfect passive soundtrack to putter around the apartment on a Sunday afternoon. D’Angelo finds Dilla, he finds Questlove, his forever producer, a recorded music encyclopedia with the chops and the range to extract and perfectly articulate whatever ideas D has floating in his infinite imagination.

There is this diminutive I find myself using when we’re arguing about the hands down, five star, timeless works. I’ll argue, “Sure, this is their most perfect album, but it’s not their best.” D’Angelo made three perfect albums, but Voodoo is also his best. It’s weird and surprising and idiosyncratic and deeply personal and incredibly horny but it’s a shapeshifter; it defies taste and subjectivity. It’s biblical and cosmic, ancient and infinite. You can play it for your grandparents or my kids, for Swifties, for Trump voters, for people who don’t speak English. There is no container on Earth it does not fill.

Voodoo followed a long five-year wait that very few artists would have had the courage or patience to sit out. He kept it under wraps until it was right. That’s how you build mystique. You can talk about your tortured process and your writer’s block and your impossible standards, but when you at last descend from the heavens with this, you have bought the undying respect of several generations. You have a place to crash, have earned the status of artist in residency in our heads for life.

But even then, even fucking D’Angelo pushes it, with an additional 14 years between projects. At the height of fame, as famous as any R&B artist in my lifetime has been, it breaks him. Because he wasn’t like most of our modern stars, media-trained chess masters with boundless talent, boundless ambition and no off switch, he was the most human of us, and couldn’t handle his fame and the insecurities it provoked. He didn’t want it, refused to be reduced to a sentient pair of cum gutters. He fucked up business relationships and romantic relationships and went into seclusion and started hitting the bottle. There were car accidents and arrests. He walked away when we all wanted him to stay, because it was never easy for D’Angelo, which made his process, the genius he could produce by force of will, all the more incredible. He was made more impressive, more perfect by his many flaws.

As suddenly as he’d left us, he miraculously dropped Black Messiah in the waning days of 2014, rewriting every Album of the Year poll, and somehow paying off a decade-and-a-half of patience with another perfect album – another work that bears little to no resemblance to the album that preceded it. It was in the mold of the Last Poets, but delivered in a soup, in a slop, with a riot going on, a perspective that is entirely his own. It was made in response to Daniel Pantaleo’s tragic acquittal, an album that, like many great works of Black American art, anticipates the trouble ahead before the rest of us can.

There is also much joy in it. Black Messiah is a wry album, a party on the deck of a sinking oceanliner that can acknowledge we’re going down and find love as a life raft. It’s an album that dropped a few weeks after my son did, and I can’t think about it without thinking about him, and new life, and those hours we spent together listening to it. And sometimes I’m jealous of my son, because what an introduction to this world.

But throw out that narrative, the arc I just painstakingly laid out, the evolution from coffee shop classicist to stardust-drenched punk supernova to revolutionary; it doesn’t do him individual justice. That portrait makes D’Angelo sound like (respectfully) a Madonna, an LL Cool J – a careerist survivor, a talented chameleon capable of constant reinvention to stay relevant with the time. What was remarkable about D’Angelo’s music is how ahistorical it is. From Voodoo on, he demands we get on his wavelength.

What does a D’Angelo single sound like? It’s slightly easier to answer on Brown Sugar, but not really. It’s at once too classic, updating Donnie Hathaway or Bobby Caldwell during an era ruled by Montell Jordan and Brandy and TLC and Soul for Real. But he was also progressive, smirking, purring and cussing in baggy jeans and a doo rag amongst Michael and Whitney and Mariah. With each project that parallel line between the sound of mainstream R&B and whatever the fuck D’Angelo is up to continued to diverge; the chasm between the two expanded, but the songs were no less potent or beloved.

“Untitled” wound up being the biggest hit on an album that spent two weeks atop the Billboard 200 and won a Grammy. What is it? A seven-minute, ten-second sex freakout performed by a choir of angels- all of whom are D’Angelo. He serenaded the audience into submission with a ballad it’s impossible to dance to at any speed. Does Black Messiah actually have distinct songs? Or is it a near hour of flow state, a dream you begin in the middle of that never really ends. Technically the lead single was “Really Love”, a gorgeous Impressions song that barely fits into Black Messiah’s noise of unrest but charted in a year dominated by The Weeknd, Rae Sremmurd, and Fetty Wap. It won him another Grammy.

D’Angelo remained erratic and elusive but when he appeared, it was always legendary. His taste was immaculate; his timing incredible. He was an early adopter of the Wu-Tang Clan and wound up singing a hook on a Liquid Swords remix. He presented himself credibly as the rap-fluent Marvin Gaye of his generation with Lauryn Hill. He linked with Common in Chicago and Snoop in LA. He jumped on soundtracks over Preemo beats with Erykah Badu and Jay-Z. When I had the privilege to see him live at the Apollo,, he was changed again, less Sex God and more James Brown – a bandleader with complete command of his troops. It remains the greatest live music experience of my life.

R&B is a genre container that never fit D’Angelo. So many people make music for a living. He was an all purpose artist who could have easily switched disciplines and cut off his ear over a watercolor landscape or taken up cobbling shoes in the Italian countryside; R&B was just his outlet. If you look at history, you really only get one D’Angelo a generation, and for some bizarre reason that perhaps isn’t so hard to understand, they always die young. In his sudden absence, the internet has been flooded by grief and remembrances, testimonials of what D’s music meant to them. We are people all trying to answer the question: How does it feel? Today it feels empty. It feels surreal. It feels like it’s over.

But maybe it’s not. There were some recent reports D’Angelo had been in the lab, that he was making music and was feeling uncharacteristically good about it. I wouldn’t be surprised if like Kafka, his last will and testament demands those loose ends that couldn’t meet his impossibly high standards, be deleted and/or burnt.

Or maybe tomorrow, maybe in a few weeks, or a few months, or a few years, suddenly, without warning, a capsule will open and we’ll discover he actually had finished a final masterpiece. He’ll touch the world with his last surprise. One last left turn of style and substance, a proper farewell from the depths of his soul that would be impossible to anticipate or even guess at. Either way, I’ll wait. And why not? We’ve all spent so much time waiting for D’Angelo. I can spend however much time I have left hoping against hope for one more miracle.