Evan Nabavian’s YouTube algorithm is chaotic good.

The hidden hand behind much of the French pop canon was a literal giant who cut experimental records between recording sessions. Bernard Estardy was born in 1939 in France and, in his daughter Julie’s telling, he was a born tinkerer. He spent his childhood dismantling household appliances and modifying his mother’s tape recorder to play 45s. Music came naturally too. A year of piano lessons didn’t interest him, but playing music was a regular pastime – he taught himself to play a Chopin waltz just by listening to it. At the same time, he immersed himself in math and physical chemistry and he studied public works, but a few months at a traditional job didn’t suit Estardy whose fixations included jazz and black holes alike. By night, he played in jazz clubs and found himself in Saint Tropez rubbing shoulders with Serge Gainsbourg. After a stint as an organist for Nino Ferrer, Estardy co-founded Studio CBE in 1966 with his secondary school classmate Georges Chatelain.

Estardy stood 6 feet 7 inches tall but he had the temperament of Woody Allen in a crowded room. The shy man with the warring left and right brain found his calling behind the studio’s recording console. Per his daughter, “being hidden in the shadows of a grotto suited him, especially since he was working directly with artists. This liberated him and he became a sort of conductor within this cocoon.” Estardy manned the mixing board for the likes of Françoise Hardy and Gérard Manset, midwifing pop records that would become emblematic of a generation. And yet Estardy had other creative interests and commercial pressures.

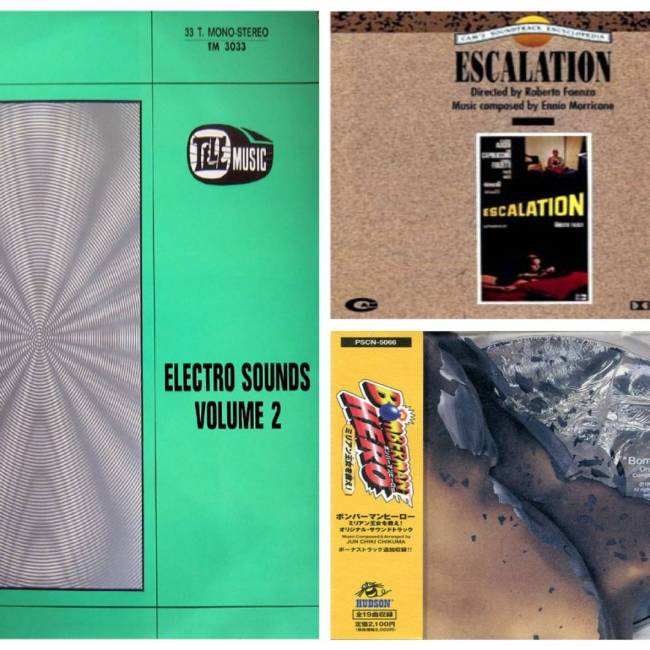

Studio CBE didn’t make real money until 1974 when mainstream acts started patronizing the studio. To make ends meet, Chatelain made a deal with Roger Tokarz of Tele Music to make library records. Estardy would sit behind his organ or grab a session musician and improvise a piece that didn’t belong anywhere else. These are the circumstances of “Coeur Polaire” (“Polar Heart”) from his 1974 record Electro Sounds, Vol. 2. An inquisitive string section plays call and response with an increasingly convulsive piano amidst deep silence. A recurrent bass tone keeps time. But then the rhythmic tone is actually a human heartbeat and it starts panicking, terrified at finding itself in an infinite void. “Coeur Polaire” plays like a spacefarer’s bad dream, though Estardy probably only intended it as a slick atmosphere.

He likely never gave these sounds a second thought. Per Julie, “He was not at all taking these pieces seriously, it was really the kind of improvisation that he could have done in his living room. Even if something was not quite right with the piece, it was not a big deal.” Estardy died in 2006 and he spent his final years playing with a train for which he fashioned two kilometers of track through the mountains. His agreement with Tele Music ensures that some of his intellectual curiosities endure.

The Gregorian chant “Dies Irae” is one of the most quoted pieces of music in Western cinema. Wendy Carlos hinted at it with her synthesizer in the opening moments of A Clockwork Orange. Nine years later, she performed it again for The Shining, this time with fewer modifications. Kubrick recognized that “Dies Irae” was well-suited to movies about psychopaths. It also shows up to evoke calamity or crisis in Star Wars (Luke discovers his aunt and uncle murdered), The Lion King (Scar kills Mufasa), and It’s a Wonderful Life (George Bailey pleads for his life back). In all of these cases, “Dies Irae” plods along like a pallbearer, slow and grim. Wendy Carlos, John Williams, Bernard Herrmann, and others who have interpreted “Dies Irae” typically omit the chanting itself and use the melody.

Wendy Carlos’ renditions deservedly get the most recognition, but Ennio Morricone made a unique contribution to the canon in 1968. Roberto Faenza’s Escalation is a pop art obscurity set in 60s London. For the score, Morricone collaborated with Bruno Nicolai and the choir of Alessandro Alessandroni – this is the second appearance of the latter in this column. How did they adapt “Dies Irae” to the era of miniskirts and The Kinks? “Dies irae psichedelico” is everything the title promises. An electric guitar performs the iconic refrain, accompanied by drums that wouldn’t be out of place on the period’s mod and beat records. Alessandroni’s choir performs the chant and magnificently clashes the austerity of a Catholic mass with the sensibilities of Carnaby Street. Morricone would interpret “Dies Irae” again in 1986 for The Mission – a more typical use of the motif – but his version for Escalation stands apart among the hundreds of attempts to recontextualize it.

The Streets of Rage games have become famous for Yuzo Koshiro’s soundtracks which contained curiously authentic club music instead of the usual fare of a 90s video game. Here is Just Blaze gushing about Koshiro. But real heads recognize the work of June Chikuma whose soundtrack for Bomberman Hero (1998) paired a middling action game with delirious drum and bass music.

The Bomberman series is known for its chaotic multiplayer matches where players attack each other with bombs on a maze-like grid. Hero is an oddball entry which eschews multiplayer in favor of a solo action platformer – per the developer, it was intended as an entry in the Bonk series and it was repurposed as a Bomberman game during development. Reviews are not kind. But longtime Hudson Soft composer June Chikuma saw fit to lace Bomberman’s solo adventure with hard-edged breakbeats. The music of the game’s opening moments is closer in spirit to a BBC Essentials mix than anything that typically came out of a Nintendo 64. A highlight from the soundtrack is “Dessert” which is slower and more atmospheric than the frenetic beats of other sections. It flips a melody that has been part of the Bomberman repertoire since the days of the NES and the TurboGrafx-16.

Speaking with Kotaku, Chikuma recalled being inspired to compose music when she heard Ravel’s String Quartet as a child. Thereafter, she started composing soundtracks and found her way to video games when her agent found her a job at Hudson Soft. Her reference points – techno, classical, traditional Arabic music – suggest an eclectic music nerd of the highest order. She said of her approach to creating music, “I don’t like to express other things except music. That might not be suitable for a soundtrack composer, because it requires a professional compromise. However, the combination and the balance of those elements seem to be interesting for listeners, having no connection with the composer’s intent.” Hence the surreal sight of Bomberman riding a rabbit through a low polygon marsh to what sounds like a cut from a pirate radio mix circa the mid-nineties.