Support real, independent music journalism by subscribing to Passion of the Weiss on Patreon.

Evan Nabavian‘s YouTube algorithm is chaotic good.

Erick Cosaque – Guadeloupe, île de mes amours | ANTILLES SERIES

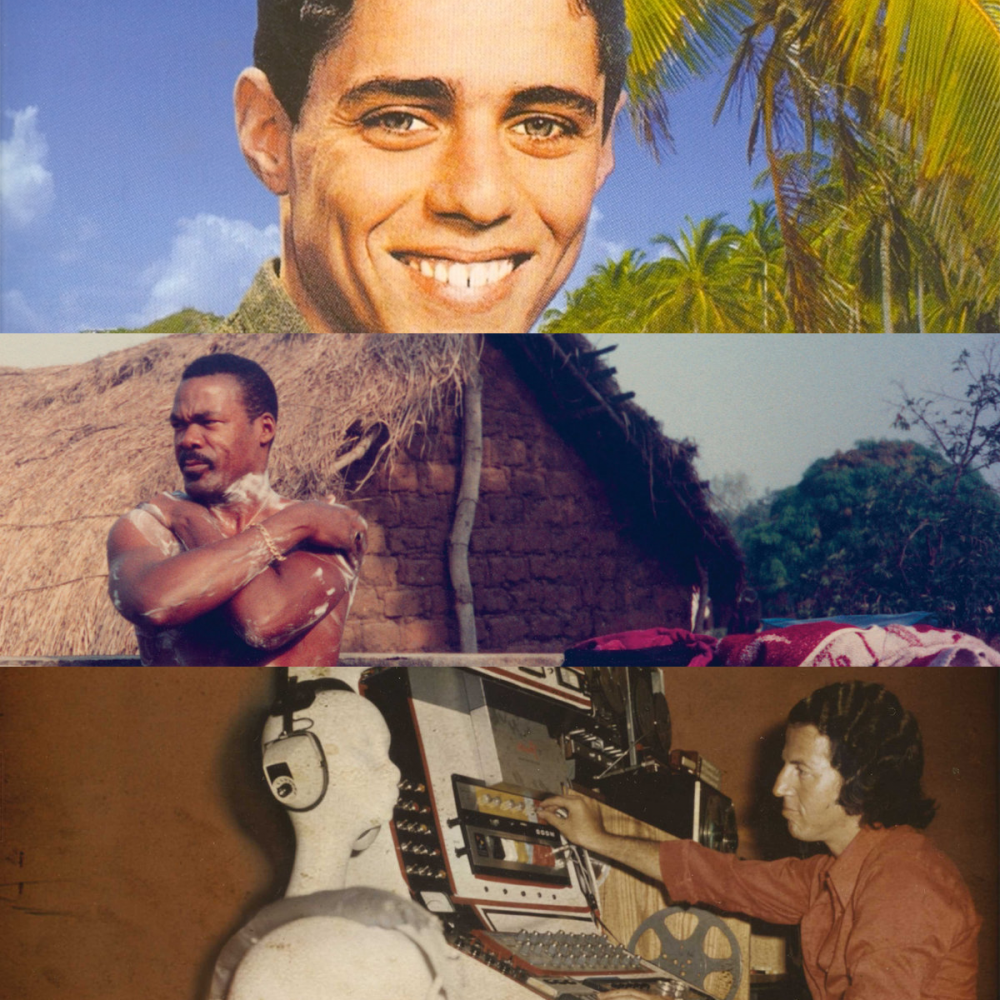

Writers who deign to define gwoka often prevaricate for several paragraphs to avoid pigeonholing it as mere caribbean drum music. Jérôme Camal of the University of Wisconsin-Madison writes in Creolized Aurality that “in its most common expression, gwoka is a music and dance typically accompanied by an ensemble of at least two barrel-shaped, single-headed drums, themselves called gwoka, or simply ka.” But this definition elides an ocean of significance. Gwoka includes the gamut of musical traditions of colonial and rural Guadeloupe – work songs lubricated with white rum, songs of wakes, the rite of a Friday night lewoz. In the 70s, the guitarist and Guadeloupean nationalist Gerard Lockel added modern instruments to the centuries-old rhythms to create gwoka modènn. When the journalist Mark Kurlansky visited Guadeloupe in 1990, Lockel advised him that drinking champagne at a lewoz was a big no-no. Gwoka is the inheritance of slaves and carries an intrinsic tension with French colonialism. A scion of gwoka is Erick Cosaque whose work was recently compiled by the French label Heavenly Sweetness. The compilation opens with Cosaque in exile, toasting to Guadeloupe from wintry, gray, iron Paris. Over lush saxophone and synthesizer, he moons after his home, its language, its children, its cane fields, its coconut and banana trees, and its shores. He vows to fly home tomorrow and never leave again. Visiting Guadeloupe in 2007, Camal found that dancehall, soca, and zouk had supplanted gwoka in the popular consciousness. But those grooves likely couldn’t evince the generational yearning that Cosaque found in gwoka.

Chico Buarque De Hollanda, Ennio Morricone – “Funerale Di Un Contadino”

In 1956, the Brazilian poet and diplomat João Cabral de Melo Neto published Morte E Vida Severina (“Death and Life of a Severino”), a dramatic poem that follows a migrant from Brazil’s northeast as he travels the country in search of a better life. The title character suffers in his journey across the arid backcountry to the point where he tries to kill himself, but he is restrained by a Christ-like figure. Today, Melo Neto is regarded as one of his country’s great poets and Morte E Vida Severina his signature work, but the author said that the public didn’t appreciate his poem until it was adapted to music.

In 1965, Chico Buarque was a fledgling architecture student who swilled cachaça and dreamt of becoming a radio singer. He participated in a singing competition where one of the judges approached him about setting Severina to music. At the time, Buarque was best known for his single “Pedro Pedreiro”, which he was tired of performing, so he accepted the offer. The play’s premiere received a 10 minute standing ovation and won local and international acclaim, including an award from a performing arts festival in France where Buarque performed in person. Buarque recorded some of his compositions for a 1968 album. Among them is “Funeral de um lavrador,” a dirge with theatrical grandeur.

Severina would transform once more in Buarque’s hands. Chafing under Brazil’s military dictatorship, Buarque absconded to Italy for two years where he and Ennio Morricone found time to record an album together. By 1970, Morricone had already earned his place in history, having just scored Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy and permanently changing the vocabulary of film music. Buarque and Morricone’s record, Per Un Pugno Di Samba (“For a Fistful of Samba”), includes a new version of “Funeral de um lavrador” backed by Morricone collaborator Alessandro Alessandroni. (Alessandroni is responsible for that iconic spaghetti western whistle and an experimental library record or two). Morricone adds madness to Severino’s sojourn in Nordeste. Arrhythmic percussion and manic birdsong stalk Severino as he contemplates a senseless death. The original features the vocal group MPB4, a quartet of men, who echo the narrator’s graveside sorrows. The version Buarque made in Italy replaces them with wailing women, ghostly spectators to the proceedings. All eulogies are paltry until they’re remixed by Ennio Morricone.

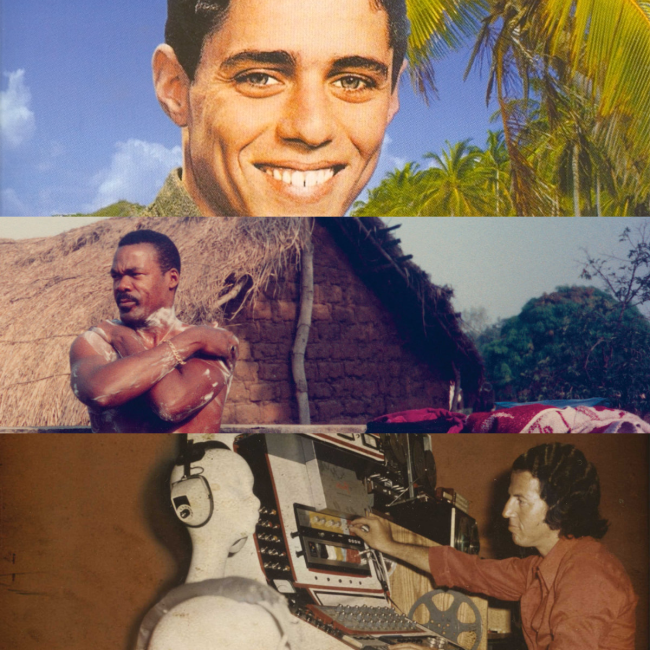

Gökçen Kaynatan – Madımak

The au courant crate digger knows all about Anatolian rock, as well he should. It is only natural that Selda Bağcan’s searing, electric “İnce İnce” would inspire Mos Def’s most progressive hour on “Supermagic” or that Gaslamp Killer would rely on the catalog of Erkin Koray to craft the psychedelic Shangri-la of Gonjasufi’s A Sufi and a Killer. One of the forebears of the much-feted Turkish psych scene is Gökçen Kaynatan whose music was rescued from the maw of history by a 2017 compilation by Finders Keepers Records. Kaynatan formed one of Turkey’s first rock bands in 1954 and cut a few singles, but he bristled at his label’s business practices – it was tough to get paid. An affinity for electronics led him to procure a portable version of the Synthi 100 synthesizer during a trip to Cologne. He spent six months mastering the machine whereupon he made some of his country’s first electronic records. Kaynatan’s career as a recording artist floundered because he couldn’t find suitable patrons in his dealings with record labels and also because in 1979 doctors found a benign tumor behind his left eye. With his recorded work left to gather dust, he found work as an architect and the in-house composer for the national television channel. Then in 2016, Doug Shipton of Finders Keepers and fellow connoisseur DJ Sofa came knocking and raided Kaynatan’s archives for a compilation. A highlight is “Madımak,” which converts a Turkish folk song into a protean digital groove. Even as his career stalled for 40 years, Kaynatan amassed legacy and influence behind the scenes of Anatolian rock: he fixed Barış Manço’s synthesizers and he played in a band with Erkin Koray when they were teenagers. A bittersweet side of “Madımak” is that its charms might have been lost to history if not for the persistence of globe-trotting groove collectors.