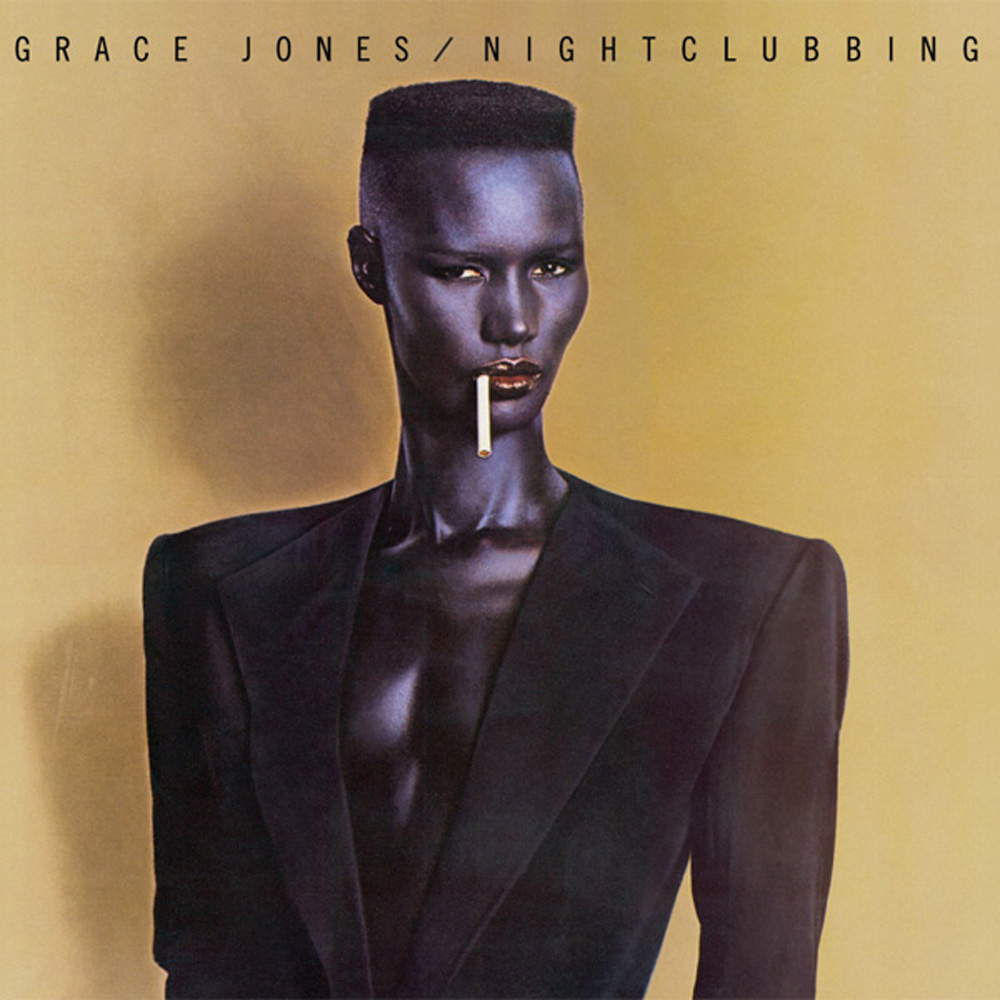

Photo via UMG Recordings

Support truly independent journalism by subscribing to Passion of the Weiss on Patreon.

By the time Grace Jones’ Nightclubbing was released on May 10, 1981, the studio band assembled by producer Chris Blackwell was already being compared to the likes of the Wrecking Crew and The Swampers in terms of the definitive sound they had established.

Jones was boldly blurring the lines of androgyny — both on the cover art designed by her ex-husband Jean-Paul Goude and her command of deep masculine voices. Between her originals and her covers of Iggy Pop, Bill Withers and Sting, Jones and this unlikely band of session musicians had created this netherworld where funk, punk, disco and reggae became one fluid sound of perpetual rhythm. It was a band that only the likes of Island Records founder Chris Blackwell could have put together at his Compass Point Studio in the Bahamas, a recording space so beloved by artists that Robert Palmer bought a house across the street.

Dubbed the Compass Point All-Stars, the crew was comprised of two guitarists — Mikey “Mao” Chung from Peter Tosh’s band and Barry Reynolds, then fresh off his work with Marianne Faithful on her landmark 1979 LP Broken English — as well as French African keyboardist Wally Badarou, then known for his work with M People. On percussion, there was Sticky Thompson from Joe Gibbs’ studio band The Revolutionaries and the premier reggae rhythm section of bassist Robbie Shakespeare and drummer Sly Dunbar.

Arguably no other collective of musicians could have pulled off the sound that the Compass Point All-Stars perfected on Nightclubbing, a record whose influence can still be heard in the most cutting edge hip-hop, rock and R&B, via the likes of SAULT, Hiatus Kayote and black midi (just to name three). And so in honor of Nightclubbing‘s 40th anniversary, Reynolds, Dunbar and Badarou shared their memories of putting together this groundbreaking music with Grace Jones and Chris Blackwell. – Ron Hart

Barry Reynolds: It was my birthday, and I was in London and had been writing music with Marianne Faithfull on the songs for Broken English. And I think there was something I did on this track called “Why’d You Do It” where I play this little out-there guitar part, and Chris Blackwell took a liking to it. He thought was this mix of heavy roots reggae with a European edge to it. So he called me down to Nassau to work with Grace Jones.

Wally Badarou: I never worked neither for Chris Blackwell nor for Island Records before he personally invited me to work on a Grace Jones album. I even hardly knew about him and did not pay much attention to record labels back then. The only thing I vaguely knew about him was reggae music as made popular by Bob Marley. Never worked with Barry before either. We met on the plane en route to Nassau. I knew of Marianne Faithfull and quite liked her “Ballad Of Lucy Jordan”, a hit in France. But I was not aware of his (and Steve Winwood’s) contributions to the whole of the “Broken English” album. Barry and I became good friends ever since.

Sly Dunbar: We were in New York, and Chris Blackwell called me and Robbie to come to his apartment to check out this singer, her name is Grace and she is a Jamaican who sings disco and lives in France. And she’s a model. So he gives us her early albums for Island and to this day I haven’t listened to them (laughs). Then he called us down to Nassau in 1980 to record with her. When we got to Nassau, the first two people we see are Wally Badarou from France and Barry Reynolds from England. So they asked what we were gonna do, and suggested that we rehearse but then Robbie said to them, ‘No, let’s just go into the studio and whatever we do, we are going to cut it because you will never get back again.

Barry Reynolds: The Jamaican musicians were incredibly tight, and it proved to be a great training ground for me, because we would do two takes of something at the most and then Robbie–who was one of the leads in the band–would then say, ‘Yeah, we good with this one let’s move on!’ Then we’d go onto something else. I learned very quickly that what you were putting down in the beginning was really important.

Wally Badarou: You could not be a Frenchman without having heard of her disco version of “La Vie En Rose”. I was far from impressed. As a fusion funk jazz musician, I used to despise Disco as a genre, because its over-simplistic rhythm meant just the opposite of what I was striving for: infectious syncopation made of subtle and original complexity. Disco was the death of funk, and I hated it for having had the likes James Brown and Sly Stone buried under the martial rule of binary snare and bass drum.

Barry Reynolds: I wasn’t really a session musician, but all the other guys were. And so I felt a little out of my depth. When I arrived there, no one would call me by my name, though Wally couldn’t speak English at the time and we were already friends. But the Jamaican guys were tough. It almost took a fight for me to gain some kind of respect, because Sticky started stealing my cigarettes. I had brought these cigarettes over from England — they were Embassy — and they didn’t sell them in America and were seldom found in Jamaica.

And so I’d have a pack on my amp or whatever and go to the loo, and I’d come back and the pack was gone. Then I look over at Sticky surrounded by all this percussion and he’s got my pack of Embassy’s. I went over to him and told him, ‘You know, Sticky, I’d give you cigarettes if you asked.’ And he says, ‘What are you calling me a thief? Outside!’ So I march out with this guy who is about to kill me and we get to the door, hands me back my pack and says, ‘Me only jokin’, man!’ And I thought, ‘Thank God for that!’ We became good friends after this, but it was almost like I had to cross this macho bridge to show them who I was.

Wally Badarou: It was the first time I worked with them. I had vaguely heard of them before. Apart from Jimmy Cliff and Bob Marley, I knew very little about reggae music. Back then, my interests were mainly in the R&B, Funk, innovative Fusion-jazz, the likes of Marvin Gaye, George Benson, Roberta Flack, Stevie Wonder’s classic period of the era, etc. The Compass Point situation was my first encounter and work with Jamaican musicians. Even though in the studio things kind of happened in no time at all, like magic, it took quite a bit of time to socialise outside of the studio. But looking back on what we achieved together under Chris’ vision, as years went by, mutual respect never ceased growing.

Sly Dunbar: I never heard of Grace before, but when Chris told me she was Jamaican, I was like ‘Wow.’ So when we got to Nassau, there was a big picture of her in the studio going from one end of the studio to the other end. And when she walks in, she looks exactly like she did in the picture (laughs). She gave off a vibe, and she was happy to speak Jamaican, because me, Robbie, Mikey Chung and Sticky Thompson were all there.

Wally Badarou: Grace’s input in the recording process itself was minimalistic to say the least. At the end of the day, the records were hers, undoubtedly. But everything in the making of them, from start to finish, was Chris Blackwell’s: the idea, the concept, the cast, the timing, the location, the picking of the songs to be covered, each and every decision, the final cut, and above all, the spirit and the mood, it was all Chris’. He and only he made us all meet in that point of space and time, and only his vision and charisma made us all deliver what we ended up delivering, absolutely nothing else.

In other words, the magic that happened was only due to him being present at every stage of the production: he wouldn’t just remotely produce from an office somewhere in London or NYC, far from it. He would be in Nassau, sitting right in the middle of us in the recording room while we were performing, and then checking the takes with us in the control room. Along with the invaluable contribution by co-producer Alex Sadkin, he’d be the driving force and soul behind the whole of the show, nobody else.

Barry Reynolds: Blackwell was a visionary as far as music was concerned, and an amazing producer. We would run through some fairly complicated things and what he would do is he’d let us go through the whole track and when we would get to the outro, that’s when we would fall into the groove because we weren’t thinking about chord changes and such. On the groove, everyone just breathed. But then we’d hear Blackwell coming through our headphones saying, ‘OK, keep going, we are going to start it from this point.’

Wally Badarou: The chemistry was revealed from day one, specially when we had a go at The Pretenders’ “Private Life” that first evening of the recording sessions. To the risk of repeating myself, Chris Blackwell had put us all together in the studio, with absolutely no direction nor concept discussed beforehand. He just assumed that it only took to have musicians whose work he liked to make things happen. It was a huge bet, which he won, I would say, thanks to his non dictatorial charisma.

When we all landed in Nassau, Barry and I were curious about Sly, Robbie, Mickey and Sticky’s ability to play disco music, while they were questioning our ability to play reggae… But once we got into the studio, things just unfold, no questions asked: each of us just did what he was best at, no self-proclaimed leader, nor self-proclaimed arranger in sight. Everyone was his own man, and there was no debate as to who should be doing what, where and when in order to make it groove. Things just went without words, as if we had been playing together for years. I guess each of us had, independently from each other, developed the sense of “listening to the others” required by any professional session, just like good actors would do, and just like any good musician should do.

Barry Reynolds: For Nightclubbing in particular, a lot of the material we covered was picked by Chris and Jean-Paul Goude, who actually created Grace in many ways. He was the one who brought in things like the Piazzola song “Libertango” and the Iggy Pop song “Nightclubbing” as well I believe.

Wally Badarou: Chris did the whole of the cover selection work. He would come each morning with audio cassettes by the dozens. That been said, if Sly and Robbie couldn’t find the basic groove, it was a “forget it” situation right away. If they did, then we only had one take. And only if the take was successful, then it was considered for fine-tuning and overdubs, all of which could be done much later, even the year after: laying down the rhythm tracks went so fast we managed to have a double album worth of material in less then ten days, primary overdubs included. Out of which Chris decided to have Warm Leatherette completed and released first that year (1980), then Nightclubbing the year after, once final overdubs were added to the rhythm tracks already recorded.

Barry Reynolds: Grace had never really written songs before, so we started writing together. We wrote “Art Groupie” as she was splitting up with Jean-Paul. And one of the reasons for the song’s direction was how much Jean-Paul was into the art scene. At the time he was doing art for Esquire and being asked to do high end adverts in France for Hermes and stuff like that. He once called Grace an art groupie, and as soon as I heard about it I thought it would make a great title for a song. But when I wrote it with Grace, it was almost like an open letter to Jean-Paul. She just gave me these lyrics written on a piece of paper and I took them home and put it together. When I came back and recorded it, I thought it sounded like an Andrew Lloyd Webber song! (Laughs).

Sly Dunbar: “Pull Up To The Bumper” was a song that I myself had written. I went into the studio and told Alex I had this song and he suggested I cut it. So I began singing over the rhythm, ‘Spread yourself over me like peanut butter.’ (laughs). I was playing and singing at the same time, and we cut the song. It was kind of R&B while most of the stuff we had been doing was more New Wave-ish. It never came out of that first session we did, because it was only an instrumental song.

I called it “Peanut Butter,” that instrumental version. Then Grace came into the studio one day when we were playing it. And this girlfriend who was with her named Dana heard what I was singing, and came up with the idea of ‘pull up to the bumper’ and we cut it with Grace singing. When I was on tour with Black Uhuru, Chris Blackwell called me and said, ‘This song is gonna be a hit!’ I said, ‘What song is that?’ He said, ‘The same song you wrote for Grace, the peanut butter song, it’s gonna be massive!’ About two weeks later, I heard it on the radio.

Barry Reynolds: I wrote “I’ve Done It Again” specifically to give to Marianne. But when I played it to her, she felt like it was too jazzy. But then Marianne came down to Nassau when we were recording with Grace. And when we went to record “I’ve Done It Again,” she goes to me, ‘We wrote that!’ And I was like, ‘No we didn’t!’ (laughs) But she did have a great verse in there that she wrote, which is why she’s credited as well. But I love Grace’s version of the song. And her and Marianne got along really well. I wish I was a fly on the wall when they were left alone in the same room. They liked the same things, let’s put it that way (laughs).

Wally Badarou: I need to repeat that Alex Sadkin was absolutely key in having all of our performances fully uplifted by proper mix from minute one. There was no such thing as a “ruff mix” with him, each mix was the mix in progress, only to be augmented by our added or modified parts. Given that back then, console total recall was still in its infancy, the overdubbing process could be quite slow, having to recreate the mix from scratch upon each tape swapping.

That was only to greater rewards after all: it is no mystery why Alex’s pristine sound of the era has been celebrated around the world. Such process was a fantastic incitement not to overproduce, each element been fully positioned in the spectrum from the word go, every small detail enjoyed legitimacy right away, and needed no extra underlining. Hence the clarity and the dynamics he managed to get from us. That was a valuable lesson I pledged to apply on my own projects ever since, only to become common practice since the advent of direct-to-computer recording and mixing technology.

Barry Reynolds: The thing about Compass Point was that its on such a boring island. That is, unless you like to gamble. And it’s a flat island, not like Jamaica. You can literally walk around the whole island. There was really nothing more to do for us other than record. And so it was a very clever position to put us in, because there were no nightclubs or anything. There was only work.

Wally Badarou: Compass Point was essential in the sense that this was the place Chris invited us all to join, an environment which incredibly slow and peaceful pace was a clear call for seeing things differently than one would back home, a place deliberately remote from any city activity (other than scuba-diving), allowing us to concentrate on the project, and just the project. It worked marvels, as long as Chris was around that is. Nightclubbing fully benefited from that situation.

Barry Reynolds: We were actually at Compass Point when John Lennon was shot, and Ringo Starr was there working on his re-recorded version of “Back Off Boogaloo” with Harry Nilsson. I remember hearing from my girlfriend in London that he had been shot, but she wasn’t sure if he was still alive. Then at around 2 AM we heard this helicopter and we knew at that point he was dead, because Ringo and Harry were heading to Miami to catch a plane to New York. I remember how it put a blanket right over us in the studio. It was on everyone’s mind and we were all in shock.

It took the wind out of all of us for a couple of days. It was sad really, because Ringo and Harry were a riot. I remember going into the studio with them when Ringo was tracking the vocals for “Back Off Boogaloo.” And there’s Harry Nilsson with a bottle of Jack Daniels on his lap and he’s like, ‘Sounds great, Ringo!’ They were both plastered. I remember Grace coming in and we sat down for the playback and Harry’s all like, ‘This is a fuckin’ hit, man!’ Then Grace turns to them and asks, ‘What are you doing drinking?’ Both of them were drinking at like one in the afternoon. Then she goes, ‘Don’t you get any exercise?’ Harry Nilsson turns around to her and says, ‘Yes, I get up and I sit down.’ (laughs)

Sly Dunbar: Grace felt the most at home, I think, at Compass Point. She was amongst Jamaican musicians. Chris Blackwell is practically Jamaican. And being in Nassau with us, the ocean is there, she was always relaxed and ready to work when she came down. We would all go to Chris’s house and have dinner. There was a real family connection during those sessions, ultimately. It was great. Sometimes I look back and wonder what it is that makes everybody love Nightclubbing. But you could see that everybody was so happy within themselves, you can hear it through the music that is being played. It gave us the vibe to really just go for it.