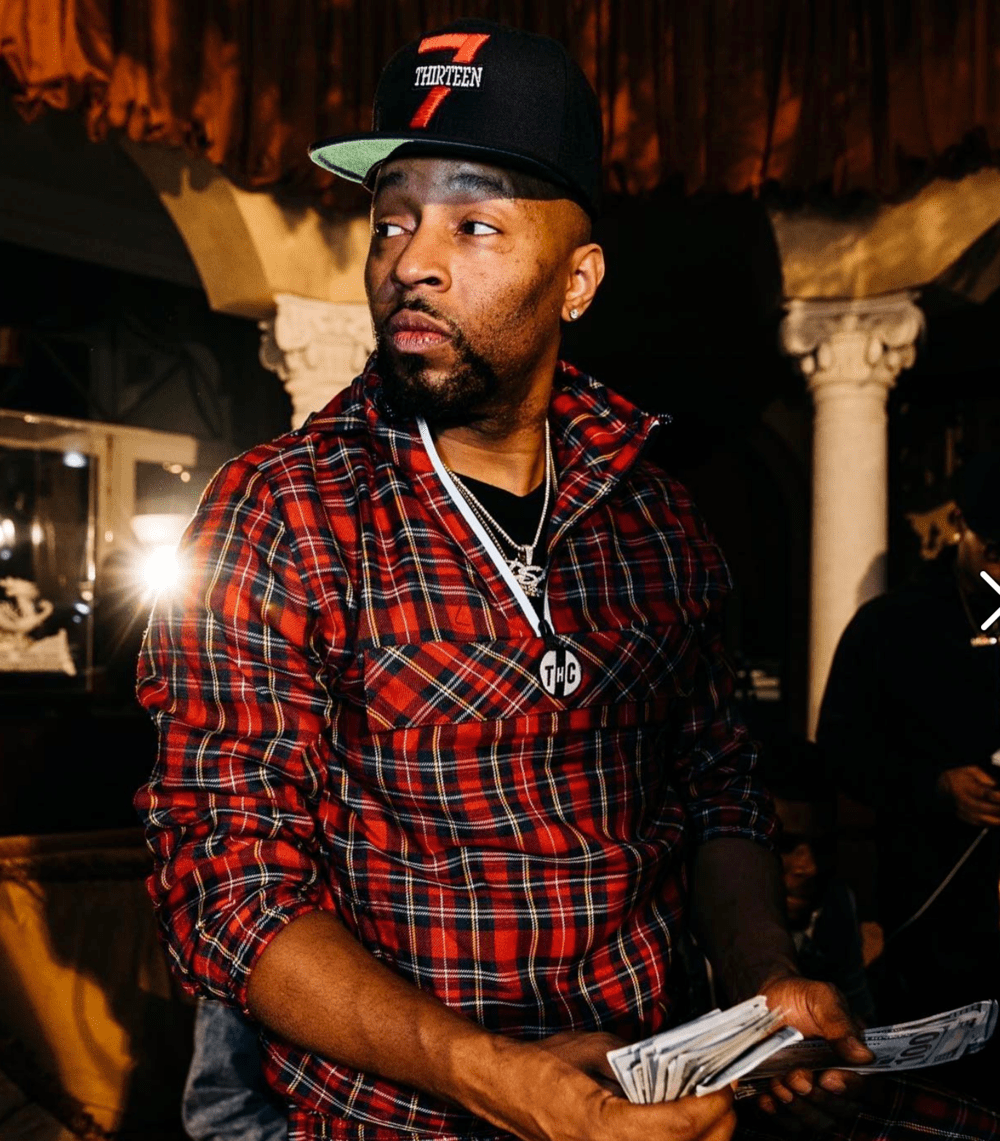

David Brake puts on for his city.

When Drumma Boy answers the phone, he sounds at peace. He’s calling from his home in Memphis, sitting poolside with his bare feet kicked up on a chair. Several karats of high-purity diamonds sit on his neck, delicately spelling out DSR, or Drum Squad Records, Drumma Boy’s label imprint. Speaking slow and intentionally, I can imagine him gazing upon his estate, taking in the empire he built.

Born Christopher Gholson, the producer was introduced to music at a young age thanks to his mother, Billie Gholson, who sang part-time for the opera, and his father, G. James Gholson, who taught music at the University of Memphis’ prestigious Rudi E. Scheidt School of Music.

A high school hustler with a penchant for long hours in the studio perfecting his craft, Drumma Boy never coasted by on his raw talent; he networked like a seasoned businessman, securing placements so consistently that he eventually grew from commenting on Memphis’s evolving sound to actively changing it.

Musical theory, histories, and technique were passed onto him through his parents, and these technical skills became important as the young Drumma Boy entered the Hip Hop landscape. At 19, he found himself featured on three songs from Rap-A-Lot Records artist Tela’s 2002 release Double Dose. Producing for the prominent figure in Memphis’ hip-hop scene, provided early credibility to the burgeoning producer.

It was around that time that Drumma also met Yo Gotti, and earned placements on the Memphis rapper’s 2003 project, Life. There, Drumma Boy began establishing his own luxurious sound: a cinematic mashup of brassy New Orleans big band jazz and dramatic, P. Diddy-inspired progressions and refrains.

These early tracks are staples of Drumma Boy’s discography, and while excellent, they hold only a crude semblance to the tones he became known for later in his career. On “Tennessee Titans,” from Tela’s Double Dose, you can hear the tension between the dominating sounds of the Lil Jon and Three 6 Mafia-era crunk music and the more melodic, clean production which Drumma Boy was developing.

In the same year that he associated with Yo Gotti, Drumma Boy had three placements on Memphis rap legend Gangsta Boo’s album Enquiring Minds II – The Soap Opera. “City Streets” is packed with hypnotic strings and traditional boom-bap drums, all tinged in the sublimated twang of Memphis tones. As the years progressed, Drumma Boy began to trust his own process more and more. He didn’t have to sound like Atlanta, nor did he need to replicate the popular sonics of Memphis at the time. His beats matured alongside of him, as he distilled these influences from Atlanta and seminal Memphis Hip Hop with the cadences of Hip Hop further north from Chicago to New York.

His early work with Southern legends piqued the interest of nationally lauded rappers. By the late 2000s, Drumma Boy went on an exceptional run, producing for everyone from Scarface and Young Jeezy to Gucci Mane and E-40. His music shattered regional barriers that upheld a bi-coastal rap hierarchy. At the time, the South was still vastly underrated. It had been over a decade since André 3000 famously heralded the South’s musical renaissance, and Memphis remained outside of the spotlight now cast on Atlanta, despite the diverse and sophisticated scene which blossomed throughout the 2000s. So when Drumma Boy was tapped by household names like Kanye West, Bun B, and Rick Ross, it wasn’t just a win for the young producer, it was a win for Memphis.

Drumma Boy has urged listeners to reckon with Tennessee by producing with keen attention to his surroundings: “I came up looking at the trap. Trap was an actual location—it was a real noun. It wasn’t a sound at the time,” Drumma Boy explains to me. “From what I saw, I painted the picture musically, and that’s what created the sound of trap.”

The Trap was in part the physical environment in which Drumma Boy grew up. It consisted of the drug dealers, the scammers, and the gangsters of Memphis. But it also consisted of mothers, fathers, and families. Like any skilled storyteller, Drumma Boy is adept at blending these contrasting elements into his music. He’s not describing Memphis through his music; he’s allowing the culture to breathe through each beat. But the Trap also represents Memphis at large—a city teeming with life and ruthless drive, only held back by structural restrictions—in this case, the rap world’s unwillingness to listen.

As the years went by, the kids who Drumma Boy remembers hovering around him and his crew began to grow up. The same children who would hang around studios were now stepping inside the booth. Among them were Key Glock and his older cousin Young Dolph. Fostering the careers of young artists is a crucial part of Drumma Boy’s ethos. “Every artist that I’ve worked with doesn’t have to rap anymore which means that they’re very wealthy,” Drumma Boy states in a matter-of-fact tone. “Generational wealth is something I’ve always wanted to focus on and help people with. Young Dolph is $20 million plus. I remember when Young Dolph had ten thousand dollars. Everybody that I’ve worked with, I’ve changed their lives.”

He’s encouraged them to flood the streets with new music and to be as prolific as they can, pertinent advice for a young artist attempting to navigate an often hostile music industry.

There was no single song or breakout hit that propelled Drumma Boy into stardom. Instead, he put in the work, welcoming incremental growth again and again, until he no longer had to seek out artists to work with—they came to him. Drumma Boy’s insatiable appetite for perfection and progress was the keystone to his success.

It wasn’t enough for him to work with Tela and Gangsta Boo. It wasn’t enough to produce for Scarface, T.I., and Young Jeezy. Not even fostering the careers of Young Dolph and Key Glock could satisfy Drumma Boy’s need to do better and more in his career. “Even to this day I still don’t feel like I’m on. I never had that feeling like I’m on, I’m off. I just know I’m good at what I do,” he said with a muted pride. Somehow, at only 37, Drumma Boy has arguably influenced three generations of Memphis hip-hop with no signs of slowing down.

Like so many of his proteges, Drumma Boy works quickly. So now it’s the right moment to stop and relisten to the legendary producer, as he explains the origin of some of the fundamental tracks that forever altered the direction of hip-hop.

“Put On” – Young Jeezy f. Kanye West

I was so inspired by the Chicago Bulls anthem. That energy—I get chill bumps just talking about it. Michael Jordan’s my favorite ball player. Watching The Last Dance—the music I made watching that documentary was on stellar [laughs]. I was so angry, so mad, and I put all that energy into the beat.

“Here I Am” – Rick Ross f. Nelly & Avery Storm

Drumma Boy live! We got the guitar, we got the bass, we got the pianist. We got everybody on this situation. It’s just priceless how we put it together. Julia Beverly called me to the studio that day: ‘I’m working with Rick Ross at Patchwerk, you should come through.’ I pulled up. [“Here I Am”] was in the top five beats I played. He was like, “I got someone to send this to.’ And he sent it to Avery Storm right there on the spot. Avery Storm did the hook, he sends the hook back, the rest is history, man. Rick Ross puts his verse on it, got Nelly on it. Here I Am.

“Never” – Scarface

One of my favorites. I made that beat to prove to New York, to the Hip Hop world that I’m not just a down-south producer Don’t get this shit twisted. I make the shit that New York motherfuckas want to rap on too. I wanted to show my versatility with a down-south artist. Scarface was one of the first southern artists that a lot of the up-north residents respected.

“Just Like That” – Bun B f. Young Jeezy

Another Texas vet. I was able to work with Slim Thug, Bun B, and Scarface. Those are my top three. I met Pimp C a few times. I wish I would have been able to work with him. But I had to work with Bun B. Getting that alley-oop to work on that song through Jeezy … moment.

“Boo” – 2 Chainz f. Yo Gotti

Aye, man. I helped so many people make it through their college years with that song. Yoooooo, all I eat is Lo Mein. People come up to me and was like, ‘yo I literally ate noodles through college’ [laughs]. That song is classic. 2 Chainz came over to my house and he recorded the whole TRU Religion mixtape in my studio at my house. When he was finishing up the tape, I didn’t have any tracks on it and I was like, ‘damn, you gon’ record the whole mixtape at my house and not even put me on the mothafucka? What kind of shit is that?’ [laughs]. So, I gave him five beats—that’s like my magic number. I swear to god, [out of] the five beats that were on that CD, three songs made it to TRU Religion. Same thing I did with Jeezy—he was done with the album and here I come with “Put On,” “Ambitions As A Hustler,” and “Amazing.” Aye, bruh, that was crazy. Same thing I did with T.I.. I end up with four on Paper Trail.

“Smoking On” – Wiz Khalifa & Snoop Dogg f. Juicy J

I made that beat right upstairs. I wanted to have a trap Cali vibe. Man, it’s going to be something smoking with Wiz and Snoop. That was right after I did “Bluffing” with Wiz. I wanted to make something with more energy because “Bluffing” was so slow. That’s another one of my favorite beats. I made “Smoking On” to have a bounce to it.

“Stove Music” – Gucci Mane f. Waka Flocka Flame

One of my favorites. Classical. I made that beat on the spot in front of Nelly, Polo, everybody. That’s why you hear Polo the Don in it, ‘Man, I love you Drumma Boy.’ Polo never made any of the beat, he paid for the studio session. He told me and Gucci to come to the studio. I came through with my beat machine. Gucci came through and that’s what we made right there on the spot.

“No Hands” – Waka Flocka Flame f. Roscoe Dash & Wale

I made it in five minutes. Gucci Mane gets out of jail, books up the whole Patchwerks studio. It’s like a celebration, a party. We got Roscoe Dash, Wale, Waka, 50 Cent, Lloyd Banks, man everybody was in there—like 200 people. I started making the beat on spot. Everybody talkin’ and talkin’. Soon as Roscoe Dash went in the booth and dropped that hook, it was a movie. Everybody started dancing.