We talk about death every day now. It’s in the air. It’s on the ground. It’s waiting on the other end of cell phones buzzing in the wee, small hours. It’s peering back at us through laptop screens. It’s wafting into windows on sirens punctuating silent nights, slicing through our illusion of calm as steel does paper. It doesn’t hang around and wait its turn. Our bodies are intricate constructs, but fragile ones, too, prone to extraordinary feats and catastrophic failings. That’s the lesson of these maudlin days, if there is any sense to be made of them. It isn’t to learn a craft or start a business, to leave behind some brick-and-mortar monument to our impact, in order to proclaim to the ages, “Look, I was here.” It’s to get good at the dash, the dash through the phases and stages of life, the dash etched in granite between our beginnings and our endings.

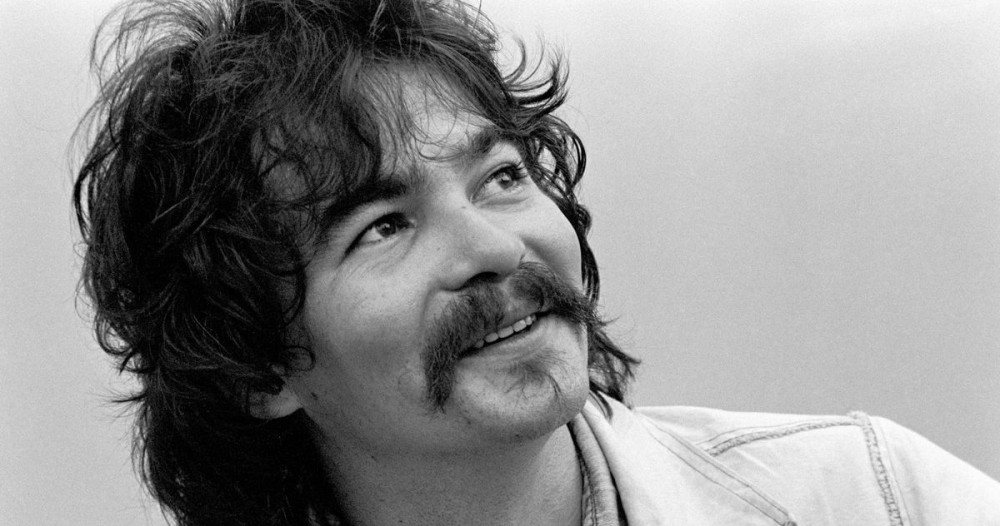

I’ve listened to John Prine a lot this month, as the 73-year-old midwestern mailman turned Nashville figurehead fought a battle with COVID-19 that, as we learned Tuesday night, he regrettably lost. His music was a celebration of the fullness and the randomness of life. This is the through line joining the writer’s earliest songs to his last ones. In just four lines, “Sour Grapes” — a song Prine wrote at 14, when he first learned how to play guitar, and years later included on his 1972 sophomore album, Diamonds in the Rough — voices our nagging hunger for order, and the songwriter’s lack of interest in it: “I don’t care if the sun don’t shine / But it better, or people will wonder / And I couldn’t care less if it never stopped raining / ‘Cept the kids are afraid of the thunder.” “Lonesome Friends of Science,” from 2018’s The Tree of Forgiveness, tells the same story from the other side of his life: “The lonesome friends of science say / ‘The world will end most any day’ / Well, if it does, then that’s okay / ‘Cause I don’t live here anyway / I live down deep inside my head / Well, long ago I made my bed / I get my mail in Tennessee / My wife, my dog, and my family.”

There’s a world of wisdom and depth and humor and levity between those two milestones, years of wise, terse koans and nonsensical yarns. John Prine could be a whimsical writer, possessed of a keen sense of absurdism that drew humorists like Bill Murray and Stephen Colbert in as friends and admirers. Diamonds in the Rough’s “Yes I Guess They Oughta Name a Drink After You” is a breakup song and a bar anthem that refuses to follow the rules about country-music weepers. There’s a smirk in the delivery and a glee in the self-medication that flies in the face of the conventional (and frankly faulty) wisdom about barflies that says they’re all aching and miserable. “Often Is a Word I Seldom Use,” from 1973’s Sweet Revenge (an album rife with songs about mortality, graced with cover art depicting the artist stretched out in the front seat of a car, smiling, with a cigarette dangling from his mouth), takes death and division in stride, its main character exiting a relationship (or a life) with a sneer: “I’m cold and I’m tired / And I can’t stop coughing / Long enough to tell you all of the news / I’d like to tell you / That I’ll see you more often / But often is a word I seldom use.”

Between verses about the quickness of death and the joys of life and love, Prine wrote jarring story songs and protest anthems illuminating faults in the American experiment. Having narrowly escaped deployment to Vietnam after being drafted in the late ’60s, he wrote pointed antiwar tunes like “Your Flag Decal Won’t Get You into Heaven Anymore,” a biting rebuke of people who mistake faith for patriotism (“Your flag decal won’t get you into heaven anymore / They’re already overcrowded from your dirty little war / Now Jesus don’t like killing, no matter what the reason’s for”); “Sam Stone,” which laments the lack of opportunities for Vietnam vets coming home with addictions and post-traumatic stress disorder (“The time that he served / Shattered all of his nerves”); and “Take the Star Out of the Window,” which calculates the human cost of overseas conflict (“Don’t you ask me any questions / About the medals on my chest / Take the star out of the window / And let my conscience take a rest).” Sometimes Prine directed these lyrics at an audience that needed to be shaken loose from its trust in the goodness of its government, and sometimes he sang in the first person, humanizing the struggle to get through the day. You see his range in a 1976 Saturday Night Live appearance, where he played the plaintive love song “Hello in There” and followed with “The Bottomless Lake,” a corker about a family trip in a busted rental car that ends in everyone drowning.

Though his writing earned the respect of American songwriting giants like Bob Dylan (who covered his fellow midwestern bard on tour and later claimed “Lake Marie,” a chilling spoken-word narrative from 1995’s Lost Dogs and Mixed Blessings, as a favorite) as well as Johnny Cash and Kris Kristofferson (who cut a gospel version of Prine and Steve Goodman’s “The Twentieth Century Is Almost Over” to close their country supergroup the Highwaymen’s 1985 self-titled debut), John Prine’s revolution wasn’t just lyrical. He closed the gap between folk, rock, and country in a manner every bit as poignant as contemporary ’70s records from the Flying Burrito Brothers, Poco, and the Band. In the early ’80s, when his contract with Asylum Records ran its course, Prine jumped ship and co-founded Oh Boy Records, the imprint that handled his music for the remainder of his recording career. Where most songwriters who started out in the ’70s sold well early on, peaking for a few years and trending slowly downward, Prine saw his best chart week late in the game, when his final album, 2018’s The Tree of Forgiveness, opened at No. 5 on the Billboard 200. He got his flowers while he could smell them; he won this year’s Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award and came to 2019’s Americana Music Honors and Awards to play and collect trophies for Song and Album of the Year.

Prine beat cancer twice, once in the late ’90s and again in 2013, bouncing back both times with duet albums of favorite country songs. 1999’s In Spite of Ourselves and 2016’s For Better, Or Worse helped ease Prine back into the rhythm of recording while giving space to gifted women in country like Lucinda Williams, Morgane Stapleton, Amanda Shires, and Kacey Musgraves. Listen to anyone who’s worked in Nashville long enough, and you’re likely to hear a story of a fond encounter with Prine, whose impact on Americana, first as a musical pioneer and later as a friend and mentor to artists, cannot be understated. If people seem shellshocked this week, even knowing Prine was up against an illness that wreaks havoc on the bodies of seniors and people with compromised immune systems, it’s because the man seemed to be unsinkable. If there is any comfort right now, it’s in the fact that he’s been preparing us for this all along, singing songs about how quickly our time among the living can slip by if we’re not careful, how we ought to work, play, and love as long as these mortal forms allow. “The scientific nature of the ordinary man,” Prine sang on the Lost Dogs cut “Humidity Built the Snowman,” “is to go on out and do the best you can.”