House Shoes retraces the highs and lows of his relationship with J Dilla, weighs in on the “godfather of lo-fi” debate, and breaks down his favorite bootlegs of the late producer’s work.

In the 15 years since he passed, the legacy of J Dilla has swelled at a rate commensurate with his catalog.

What was already an era-defining run at the spiritual center of the Soulquarian movement extended well into the producer’s afterlife with more than a dozen official posthumous releases of previously unheard material culled from his vault, and later, a storage unit literally spilling out with hundreds of tapes, sketches, letters, records, and zip discs discovered by a local Michigan record store owner. The contents of that unit were rightfully turned over to Dilla’s mother, Maureen Yancey (better known as Ma Dukes.) And ultimately, the trove was batched and disseminated unto us.

But regardless of where you stand on precisely what the estate was obligated to do with a freshly-unearthed trove of new-to-you material, it’s hard to scale just how influential those tapes have been over the years. And it’d be full-on negligence not to acknowledge just how similar this strain of almost cosmic intervention is to other instances in which J Dilla’s unreleased music has gone into circulation, both with and without his consent. Well before his death, the producer’s beat tapes were widely considered early blog era grail. Passed around through internet back-channels, forums, and MegaUpload links, the tapes (and the countless bootlegs they birthed,) were said to be intended for rappers as a catalog of Dilla’s most recent output. But as we all know, industry folks have sticky fingers, and those unauthorized collections are now widely available, often in full, on Youtube.

The ethical debate here is robust and it’s not really one worth delving into at the moment. But we did find an overqualified Dilla scholar and sparring partner in House Shoes, whose relationship with the late producer went from dear to rocky to reconciled in a matter of just a few years, and whose collection of Dilla’s work is virtually unmatched.

Speaking with Shoes, it’s easy to get lost in a shared reverence for Dilla’s production style and ability. Candid, adamant, and as passionate as ever, the LA-based producer, DJ, and label chief, retraced the highs and lows of his relationship with Dilla, broke down his favorite set of bootlegs, and weighed in on the whole “godfather of lo-fi” debate, hailing Jay Dee as a producer obsessed with fidelity who remains unsurpassed to this day.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

When did you and J Dilla first cross paths?

I met Dilla at Street Corner Music, which is a record shop I worked at in Birmingham, Michigan, on 13 Mile in Southfield, about five miles north of the city border. He walked up in the shop one evening a couple hours before close, and there was just something a little different about him. He was digging and had a stack of records. When he went back to the listening station, you could tell that something caught his interest. He would bring the needle back and then take the headphones off and just go into outer space for a minute.

I came to understand that’s when the beat was made. A lot of cats have ideas in their head and they can’t bring them to fruition. But that’s why Jay was just different. It really was a matter of just turning the machine on and creating what was in his head.

So you had no idea who he was when he walked into that record store?

Hell no. To keep it 100, bro, when he died, the majority of that city didn’t know who that man was. People have definitely been very revisionist about how they were looking at things back in the day. He was not held up by his city at all.

But this was when? Mid-’90s?

It’s like fall of ’94. But you know, we chopped it up when I got off of work. Smoked a joint in a white Ford Ranger he had out in the parking lot. Told me that he had just started fucking with [A] Tribe [Called Quest] and [Q]-Tip and The Pharcyde. And he was like, “You want to hear some shit?” He popped that tape in, and it was a fucking wrap.

I had just recently been hired to DJ at St. Andrew’s Hall every Friday. So I had the platform and we just got tight. I kind of became the local legs for those records. There was a few times he would be so excited, he’d call me and be like, “You’ve got to come over to the crib right now.” The first time was [Steve] Spacek’s “Eve” remix. And I made those records classics in Detroit.

Was there a healthy record exchange between you?

I would take records to him. Sometimes I would make a beat with something and be like, “Jay could do that a lot better.” I just wanted to hear his interpretation of the records.

I didn’t really understand the full story until after he passed, but the craziest instance of that is a mix CD they gave out at his funeral with these testimonials from all of his industry associates. Erykah [Badu] was on there talking about how they were working on Mama’s Gun at the crib in Conant Gardens. He told her to go pick a record out and she picks the Tarika Blue record I gave him and finds the “Dreamflower” loop.

How did you feel about him moving out West?

We were actually beefed out at the time. We had a situation. He had called me one day and was like, “Shoes, I got a DJ gig in Toronto. I don’t feel like going to storage to go through my records. What record shop in the city has the largest quantity of my releases? I’ll just go buy them all over again.” At the time, I kept a long milk crate with literally every record he produced up to that point. And I was like, “Just come grab the crate and bring it back when you’re done.”

He came and got them and went to do the gig. A week later I was like, “Where are my records at?” And then a couple more days passed and I told him “Bro, I need you to bring me those records back. I need to play those records. Those are my favorite records. You asked me for a favor and I held you down. Bring my shit back.” So he tried to pop off with me. It was his daughter’s birthday and he was just being kind of short. And I wasn’t feeling that shit. I’d seen people dick handle him so many times. They just wanted to be close to him, so they would hold his balls. Not me, homie. I was like, “You can come over to the crib or we can roll around on the fucking front lawn.”

And then he dissed me on the Jaylib album off of that. He did the song with Guilty. It was hilarious and so perfect. I literally drove Guilty over his house. Makes the homie that I forced him to fuck with basically a co-conspirator almost. Fucking hilarious.

Sounds like it was a really well-placed hit in that way.

Well, yeah. But we squashed it. He came back with Jaylib for the Detroit Electronic Music Festival in… what was that? ’03 or ’04? One of our go-betweens linked us up. I have a video of the [Jaylib] show that night at Hart Plaza. J Rocc was DJing, and he played “Beej N Dem” and Jay did this shit when Rocc cut it at the line. My homie who was on stage with him called me while I was DJing at the Buddha lounge and he’s like, “Yo, Dilla, Shoes on the phone!” [Dilla’s] like, “Everybody say what’s up to House Shoes!”

Were you keeping in touch when he was in LA?

We would talk once in a while. It kind of never was the same, but he would hit me once in a while and I’d hit him once in a while. I’d find a record and be like, “Yo, you got this record?” Or he’d hit me like “You got this?”

Then I went and saw him in the hospital. Stayed in there with him for a week when he was sick in ’05. He played me a bunch of The Shining and I would just play him joints all day. It was good, man. It was good to just be there with the homie.

It was actually kind of strange because Questlove had initially put the word out that Dilla was sick. We didn’t know if it was rumors or whatever the fuck. So I just went straight into emergency mode. Got my dude’s phone number and got the number of the room at Cedars-Sinai. Called the hospital room. Ma Dukes answered the phone. “Who is this?” I said “It’s Shoes.” The phone went quiet for a minute, but then she got back on and told me, “He said that you’re the only person that he’ll talk to right now.”

Oh, wow.

I was like, “You in there, bro? What’s the word? I’m coming out there, fuck that.” Got on a plane, hung out in LA for a week not knowing six months later, I would go to his fucking funeral. The night of that funeral, a bunch of people were at Little Temple, which is now known as The Virgil. And I got blackout drunk. No recollection of anything. I was just sad and angry. I remember going across the street to the 7-Eleven because I ran out of cigarettes and they had the Hostess Donuts display. And I bought all of the donuts off the Hostess display, went back and started throwing them at people. Like, hard. I’m not sure who was DJing, but I was on one. I wasn’t feeling the way the DJ was playing. I went up and I was like, “Jay wants me to play some records.”

Like I said, I have no memories of this. But they said I was sobbing the whole time while I was DJing. [The Beatjunkies] are up on stage, everybody’s just like, “Whoa, what the fuck is going on right now?” The next day, me and Wajeed met up for lunch and he was like, “Yo, I know we were talking that New York shit, but you planted a hell of a seed last night.”

Two months later, Proof died and two months after that I moved to Los Angeles. So he’s responsible. Like it’s his fault I live in LA now. It’s his fault that I have two beautiful children with a woman that I met in Los Angeles.

That’s beautiful, man.

Absolutely. I’m not a religious person at all, but I feel truly blessed and just honored to have been able to help. That’s always been my job. I’m just here to help.

Have you been keeping track of the posthumous releases over the years?

I’ll say this, When you’re dealing with an artist who is no longer on this planet, the most important thing to strive for is accuracy. Jay was so specific about the music he wanted the world to hear. If he wanted the world to hear that shit, he would have let them hear it. You remember there used to be all the New York hip-hop bootlegs on vinyl? Well, they bootlegged Another Batch. He was hot about that shit. Somebody pressed up like 500 copies. That shit is on vinyl, bro with that super generic ass New York bootleg font on the label. Super bootleg. He was like, “That shit wasn’t for everybody. That’s a CD I submit to managers and artists and they pick what they want to rock.”

But at the end of the day, the posthumous releases made him a man, for better or for worse. There’s positives to that, too. No one’s perfect, but Jay’s discography was more or less perfect.

But for an entire generation, those bootlegs and the beat tapes that circulated online over the years, were our main point of entry to Dilla. So the posthumous releases are almost an acknowledgment of something it seems we all sensed, which is just how much there was to still here. And then there was the storage unit situation.

Yeah, that was crazy. Just crazy how the universe work. We got it back. But it’s not the first time that happened. You heard the Amp [Fiddler] barbershop story?

I have not.

Jay moved from Huntington Woods to Clinton township, out in the burbs, in probably 2000-ish. And when he moved, a stack of his zips disks came up missing. Probably a year later, Amp Fiddler’s in a barber shop, and some dude walks in off the street with a brown paper bag. Says, “Yo, Man. I got these zips. Got these Dilla zips.”

Amp probably gave him 50 bucks or 100 bucks, and then hit up Jay Dee, and was like, “Yo, man, you’re not going to believe this,” and told him the story and Jay was just like, “Man, fuck them beats. Fuck that old shit, I’m on some new shit.”

So they were in storage for a reason. But no one can deny how influential those tapes have been over the last decade. I know you’ve got your stash of them. Any standouts from your collection?

Well, for me it’s three records. Technically two, but kind of a third one. I want to say it was ’98. There were these two bootlegs that came out called Slum Village Unreleased: Volume 1 and Unreleased: Volume 2. Basically, it was like Fantastic 1.5. It was the in-between point. They had early versions of songs off [Fantastic] Volume 2. It had “Hood Ho,” and “1, 2, 3, 4,” the Pete Rock version of “Once Upon A Time,” and the Atomic Dog version of “We Be Dem.” They sleep on that Pete Rock version of fucking “Once Upon A Time.” That shit is nuts.

And then “Do Our Thing,” which never properly came out, I don’t think. And the OG “Get This Money” version with a fucking typo on the label. It says, “Get This Monkey”.

That’s ridiculous. But why are these the ones?

At that time, these songs weren’t available on anything else. They never properly came out. Like I said, it’s like Fantastic 1.5 , the skeleton of what Volume 2 would become. I had all the other shit.

But when these three records came out, it was like “Oh shit, they’re imports.” Nobody was trying to pay $30 for these, I’m buying doubles of each. I always just wanted to have the shit that no one had, so I could crack heads with it.

Those three records contained all the secrets at that time. That shit hadn’t really surfaced. Internet wasn’t really popping yet like that. There wasn’t a lot of sharing going on. So even looking back, 20-plus years later, that’s the shit I will put in my bag if I was going to go out to play.

What do you think about him more recently being dubbed as a “lo-fi hip-hop” originator?

That’s the most disrespectful shit I have ever heard. Are you kidding me? A motherfucker that was so adamant about his shit being sonically so present. Lo-fi literally means it sounds like shit. It means low-fidelity, it means poor sonic quality. He’s not the fucking father of Lo-fi. Like get the fuck out of here.

Yeah, I never really understood the association, personally. His mix always sounded really big and detailed, even on the beat tapes.

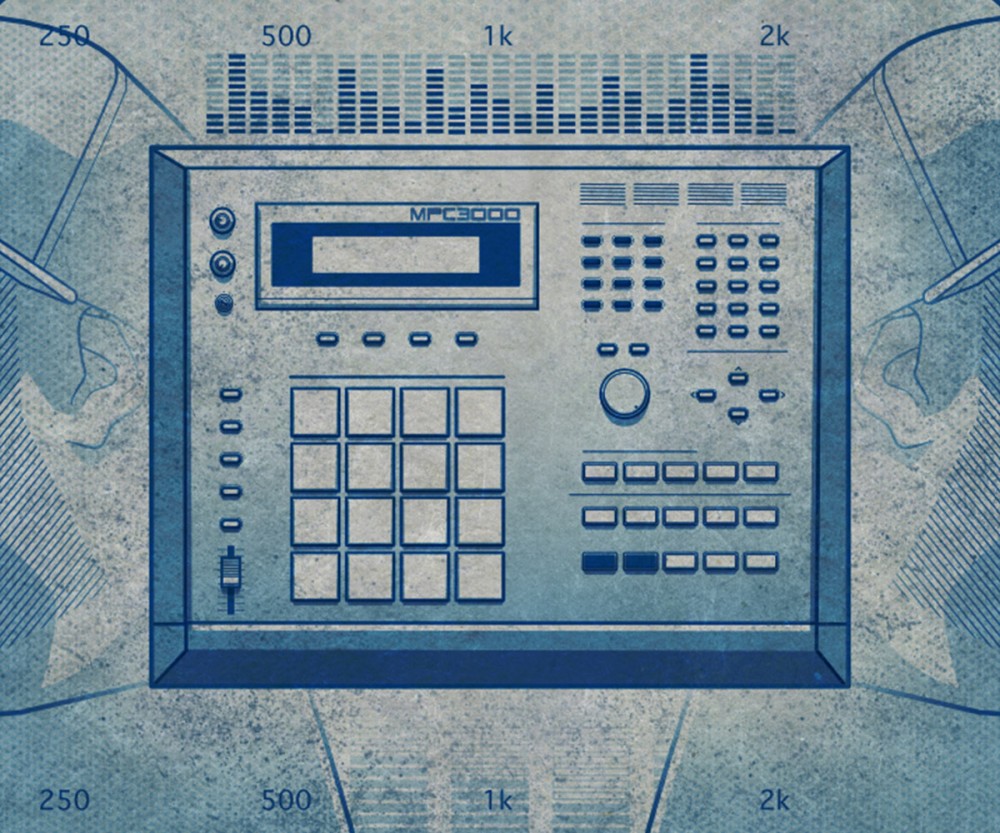

That’s what people don’t understand, man. That shit was out of the box. That’s straight out of the fucking MPC. Not in a studio. Not running it through anything. The shit was finished and you didn’t need to touch it. The reason he did that is because all the engineers were destroying his tracks. And it’d be a very well known engineer. To this day, “Drop” sounds awful to me. The snare on it sounds so outrageously fucking misguided in the mix.

And there was the era, probably 2002, 2003, where those major label placements were stereo two tracks. He was like, “I’m not tracking that shit out. It’s perfect.” No one’s going to touch the beat. I used to say that he stayed 10 years ahead of everyone. But he’s been gone for 15 years and I have not heard a better producer. People cannot interpret those sources like he did. Nobody else could make a beat out of a record like Jay Dee.

Banner Illustration: @popephoenix for Okayplayer