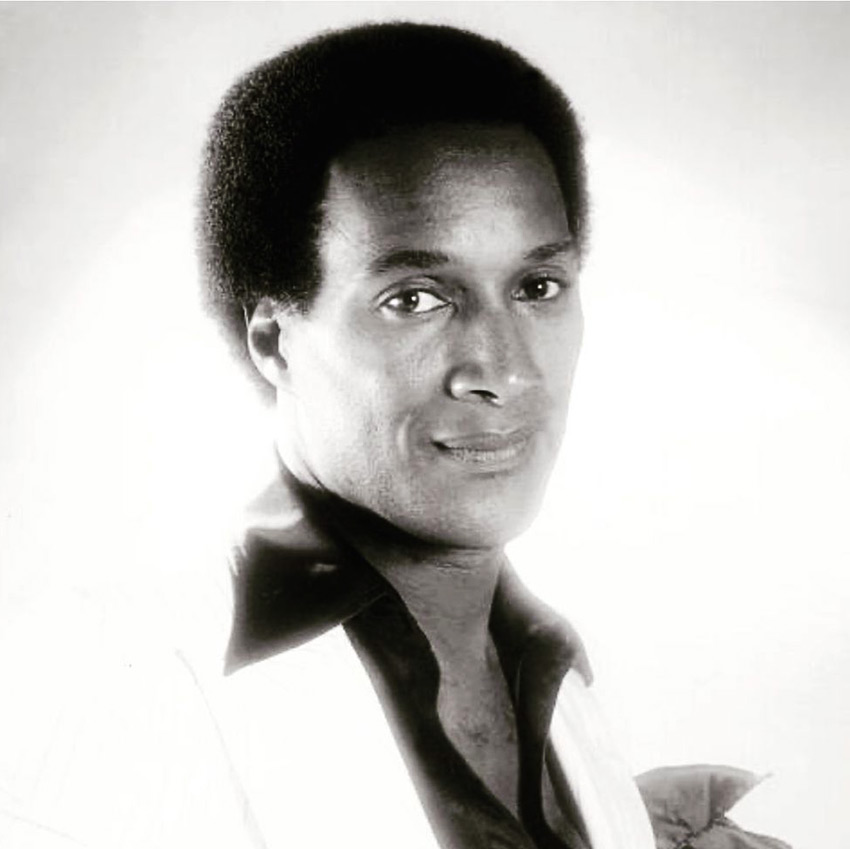

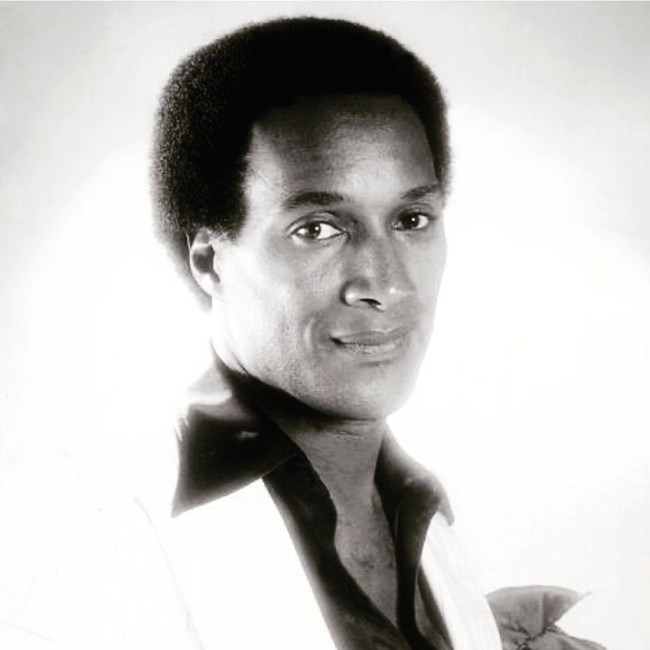

Photo via allthingsmooney

TE P. is the purveyor of all things good, including his Talks With TE Podcast.

Comedy used to be the great equalizer. It was our sincerest mirror. It showed us who we were and made our ugliness palatable enough to laugh at. It forced closed room conversations to be had in the open. It brought the flaws, the wrongs, the ills of everyday life and sat them square on our tv dinner stand so that we had to look to one another and ask the questions that no one wanted to ask. It brought us together–and so did Paul Mooney.

For as alienating and uncomfortable as some–if not most–of Paul Mooney’s stand up is, his legacy will largely be rooted in his undeniable ability to recognize talent and share it with the world. The late and great John Witherspoon, whom Mooney championed and adored, spoke of Mooney’s capacity to give up-and-coming comedians a shot on a dated episode of Jamie Foxx’s “Foxxhole Radio.” Between Foxx giving a spot-on impression of Mooney and Witherspoon sharing three decades worth of comedy gossip, “Spoon” says, “One day, Paul came into the Comedy Store and told us, “Richard is making a show at NBC and I’m gonna get everyone a job!”

Richard Pryor has been largely regarded as the greatest comedian of all time. On the other hand, he’s also been regarded as one of the greatest partiers and trainwrecks of all time. In 1977, at the height of his career and madness, NBC didn’t want to miss out on the Pryor-train. So, they gave him an 8-episode series order and hoped he would be able to deliver. By this time, Paul Mooney had become much more than just a writer for Richard. He was his conscience, his handler, and his business partner. To make this whole thing come together, Mooney brought some of The Comedy Store’s finest into the fold. Tim Reid, Robin Williams, Sandra Bernhard, and Marsha Warfield all got a shot to punch and land jokes on Pryor’s show. Even though it only aired 4 episodes, the precedent had been set and history had been made.

The magic in what Mooney brought to Pryor, and comedy as a whole, wasn’t so much so the jokes. It was the perspective. Thinking of sketches like “First Black President” makes so much sense now. But in 1977, it was as far-fetched as man going to the moon was in the early 1960s. Mooney was a product of an America that overtly stated its planned limitations for Black folks. He was also a full embodiment of the creativity that is born out of a community that continued to make a way out of no way. And his work showed it.

Having writing credits on shows like Sanford & Son and Good Times is no fluke. As the country began to change, so did our programming. Characters who otherwise served as brief moments of comedic slapstick became mainstays with developing stories. Fred Sanford was every bit Archie Bunker as he was a 60-something year old, Black, widower trying to navigate a down on its luck junk business, and a son who wanted more but couldn’t leave his pop by himself. The Evan’s were the Brady Bunch to any Black family living in the projects who weathered many storms and still found solace in one another and their community. TV has always been a reflection of where this country was headed and the laugh track reinforced our agreement with its themes. So, as Fred Sanford was adjusting to a next door neighbor who foreshadowed LA’s rising Latino population, the Evan’s resisted the crippling experience of poverty that was engulfing Black and Brown people in most major cities.

Mooney’s influence in the continuous conversation of race, politics, and our splintered relationship with America never waivered. Neither did his inclination to help rising comedians. He wrote with Damon Wayans on In Living Color. Lending ideas and the workings for one of its most memorable characters, Homey D. Clown. He sat in on standup sets and gave comics tips on letting their audience breathe and giving them a chance to decide if they were funny or not. He even ingratiated himself with a brand new generation of TV viewers who couldn’t wait for his unrepentant and downright genius segments on The Chappelle Show. If there was a moment for thoughtful, shrewd commentary on America’s current racial consciousness, Paul Mooney was there.

In his book, Black is the New White, Mooney describes his first encounter with Richard Pryor. He was so shocked and appalled by his behavior that he didn’t necessarily know what to do with him, but he knew he was honest. No matter what the view is on Paul Mooney, his comedy, his interactions with people in and outside of the industry, whether people liked him or didn’t, a common thread through all of it is his honesty. Life is not easy. At times it’s damn near too difficult to get through. But comedy is the break that helps us rise for air and muster up enough energy to keep going. Paul Mooney knew this better than most. He contextualized societal dysfunction and tried to make it funny. Sometimes it landed, sometimes it didn’t. But at least he tried. For over 50 years he tried. And for that, we should all be thankful.