Jordan Ryan Pedersen is in a heavy JRPG mode, so if you’d like to talk to him about Octopath Traveler, feel free to slide into his DMs.

Before them, there was the boom: in the 80s, there was the silky smooth AOR of city pop, stately consumerist soundtracks in the form of kankyō ongaku—“environmental music”—and visual kei’s theatrical heavy metal. These were the sounds of the Japanese economy scraping its way out of the post-war doldrums, outpacing the west on their way to total domination over automotive and technological production.

Apres eux, le deluge: the chaos of Kansai. The modern Kansai noise scene erupted out of the earth like a John Zorn obsessed-Angel, NERV apparently nowhere to be found. In the late 80s and 90s, the region that includes Kyoto, Osaka, and Kobe—which a generation before was the birthplace of the Japanese protest folk movement—birthed scuzzy girl-punk innovators Shonen Knife, psychedelic dark wizards Acid Mothers Temple, and Boredoms, the weirdest band ever to play the main stage at Lollapalooza—thanks to Kurt Cobain.

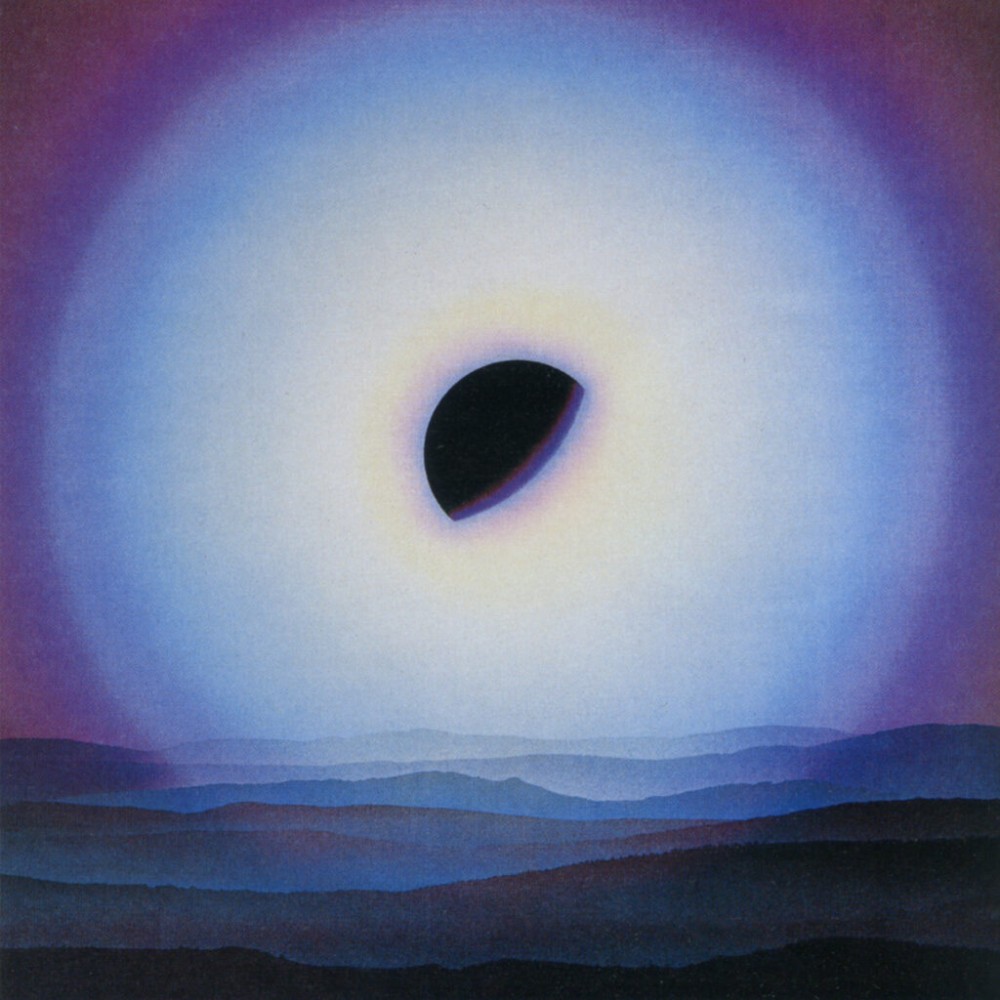

In the middle, well, is Somewhere Between, the latest entry in Light in the Attic’s increasingly essential Japan Archival series. The first four iterations covered the aforementioned city pop and kankyō ongaku, as well as the Japanese folk-rock scene that flowered in the late 60s and 70s. Their new compilation—subtitled in classic Light in the Attic fashion “Mutant Pop, Electronic Minimalism & Shadow Sounds of Japan 1980–1988″—covers the end of the period in which major labels dominated the Japanese musical landscape. It was a time where the oddballs of the 70s and 80s started to usher in the next phase of Japanese music. That many of said oddballs were still major stars is a testament to the enduring and beautiful strangeness of Japanese pop culture.

It’s Yellow Magic Orchestra who act as a sort of Rosetta Stone for understanding the evolution of Japanese music in the last part of the 20th century. YMO did everything. They had an international hit with “Computer Game,” which sold almost half a million copies in the States. Afrika Bambaataa liked to say that YMO invented hip-hop. Quincy Jones played “Behind the Mask” for Michael Jackson, who loved it so much that but for clearance issues would have put it on Thriller. Eric Clapton ended up being the one who recorded a cut of it stateside, which is sort of like if you ordered a steak but the waiter brought you a bag of dog shit. YMO—in the form of Haruomi Hosono and unofficial “fourth member” Hideki Matsutake—appear on three tracks on somewhere between, Hosono as songwriter and Matsutake as programmer and synth player.

Kyoto’s Kaoru Sato is another prime influencer. He’s the principal figure behind R.N.A. Organism—whose shuffling, burbling “WEIMAR 22” seems destined to be sampled by Madlib—and he worked a number of the other artists who on Somewhere Between. He’d go on to collaborate with noise god Merzbow decades later. Music journalist Yuzuri Agi founded Osaka’s Vanity Records, a clearinghouse for many of the scene’s new sounds—he’s credited for “conducting & leading” on the R.N.A. Organism cut. These are the envelope pushers, the ones determined to push things forward. Think Q-Tip making sure the drums snapped on The Infamous, Teddy Riley hiring a 19-year-old Pharrell to write his verse on “Rump Shaker.” The best artists are always the best teachers.

The principal strength of the period covered by Somewhere Between—that it was far less monolithic than the period that preceded it—translates into an understandably less cohesive collection. We get Steve Reich-style minimalism on Mkwaju Ensemble’s “Tira-Rin,” bleary dream pop from Sonoko on “Wedding with God.” “Days Man” comes from Yoshio Ojima, who also appeared on Kankyō Ongaku. It feels more in line with that compilation’s hushed, hypnotic beauty. Where the Pacific Breeze compilations were united by conventional songcraft—if not genre—and Kankyō Ongaku by sound and statement of purpose, Somewhere Between feels like a bit of grab bag.

But the destruction of a monoculture is a worthy goal, consistency being the hobgoblin of little minds. And destruction is necessarily violent. Mishio Ogawa’s “Hikari No Ito Kin No Ito” and Takami Hasegawa’s “Koneko To Watashi”—in their slightly restrained strangeness—feels like canvases that bands like Boredoms and Ruins were destined to rip to shreds. Somewhere Between reflects the messiness of the splintering of consensus.

Jeff emailed us this week to say the site was doing a list of Biggie’s best songs for no reason other than that Biggie was great. Isn’t that the kind of stuff you want to support? Hit us up on Patreon, yeah?

Jeff emailed us this week to say the site was doing a list of Biggie’s best songs for no reason other than that Biggie was great. Isn’t that the kind of stuff you want to support? Hit us up on Patreon, yeah?