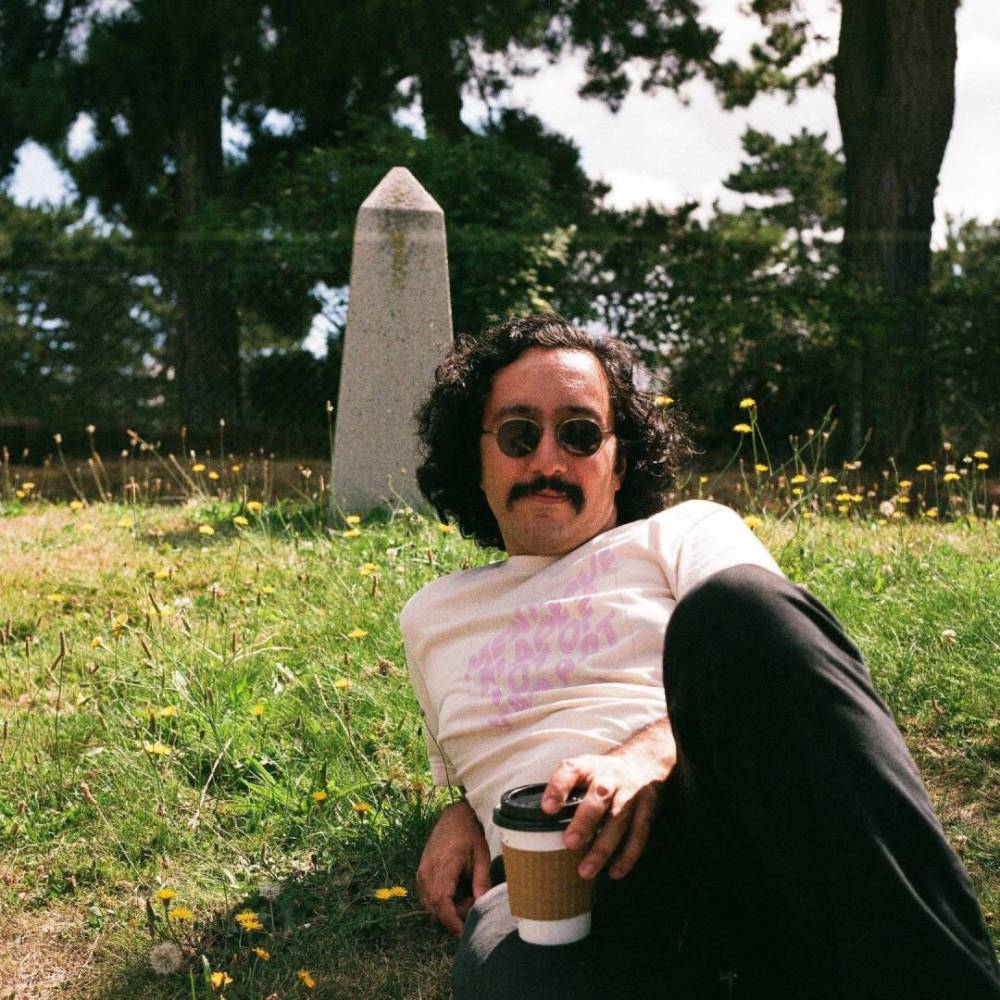

Image via Kate Van Ness

Michael McKinney understands the cultural importance of Kreayshawn’s “Gucci Gucci.”

If you run a high-level survey of the United States’s dance-music scene, a few clear hotspots spring to mind: New York, Detroit, Chicago. Zoom in just a bit, though, and you’ll find it everywhere: retrofuturist acid and breaks in Colorado, steely-eyed techno and drum-and-bass in Minneapolis, wigged-out IDM and Latin electronic in Miami. In that context, Seattle’s club scene stands tall: Over the decades, the city’s countless DJs have created a universe of creativity, with umpteen ideas blaring from speakers in abandoned buildings and basement parties. Its musical legacy may be tied to grunge and alt-rock, but the Emerald City has nurtured an everything-goes and deeply inclusive approach to club music, too. Some of the best DJs on the planet—CCL, livwutang, Succubass—cut their teeth there, and its best club nights rival those of far larger cities. You’d be forgiven for being unaware of this. For all its talent, the city hasn’t yet broken out on a national level. But maybe that’s okay. Music scenes are built and maintained by the people who stick around: Local promoters, DJs working desk jobs, and ravers meeting up with their friends every few weeks.

‘nohup’, a.k.a. Seattle club-night mainstay Bobby Azarbayejani, is well aware of this. They grew up going to hardcore shows, listening to noise music, and making wigged-out techno. (Their introduction to electronic music came early; their older brother was a trance DJ.) They hit the decks at the University of Maryland’s WMUC as they were getting into dubstep, and by the time they graduated, they were all in. They moved across the country to Seattle and quickly found their way into the local scene, going to club nights and meeting with label heads. Their musical practice has always been indelibly linked to their communities, whether it’s afterparties at friend’s homes, carefully curated college radio shows, or back-to-back sets with other local DJs.

Since moving to Seattle, Azarbayejani has only deepened their roots. A few years ago, they founded Illegal Afters Tracks, a label dedicated to oddball club tracks from fellow Seattle club-night producers, and they help run Ground Hum, an experimental music festival that recently finished up its third year. Their DJing has gotten deeper, weirder, and more exploratory: tune into a ‘nohup’ set and you’re liable to hear wigged-out dubstep, vintage deep house, and turn-of-the-century breakbeats, all delivered with an undeniably madcap energy. A friend of Azarbayejani once likened their style as a one-person back-to-back, and that assessment still holds.

On a purely aesthetic level, Azarbayejani’s style recalls what makes Seattle’s dance-music scene so great. It is playful, historically minded, and carefully constructed at once; at its best, each blend comes off like a contained explosion. But it’s Azarbayejani’s unrelenting focus on community that makes their work so critical. It’s present in their hyperlocal label work, and it’s central to their focus on involving Seattle’s dance-music community; it’s in their own gradual immersion in Seattle’s club culture. This kind of slow-and-steady growth, eventually, pays dividends. This is what a blossoming dance-music scene looks like.

Back in September, we caught up with Azarbayejani ahead of their performance at Kremfest 2023. We went wide, digging into their history with DC’s hardcore scene, how they try to bring joy to experimental music, YouTube wormholes, their relationship to humor on the dancefloor, and plenty more.

(This interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.)

Going towards music, before I really got into electronic music, or club music of any kind, I was more of a hardcore kid. I grew up around the DC area, so there was a lot of that. It’s funny—there was a pretty strong scene there; I was really young. I was 13 or something, and I saw that, and I knew that was what I wanted. That reflects from then to now, a bit.

That’s how I started to get involved here. I used to do visuals; I did visuals with a friend of mine, [Aashish Gadani], who lives in New York now. [The visual project Bobby and Aashish collaborated on was called Coldbrew Collective.] We were doing, like, one show a month for them. Slowly, though, we wound up doing three a week for all sorts of other parties. We have a community that comes together to build stuff without much outside help—not to discount the fact that there’s clubs and such in Seattle. But we worked together, and that’s awesome.

We did that once a month for two years or so. At the same time, around when I arrived here, it seemed like there was a graduating class of people that arrived, and everyone was really into electronic music. The secondnature crew had just basically all graduated from college. I made friends with them. It’s funny; nobody knew that I made music until 2017 or so. I wasn’t really talking about it. [laughs] That was the turning point: This part of myself was seen.

I used a YouTube downloader to download everything, which took a crazy amount of space. So I’ve been digging through that; it’s a lot of bad music. That’s another thing about digging: one of the things I say about digging is that I’ve listened to hours of terrible music to give you this DJ set. I’ve listened to a hilarious amount of terrible music. I’m just sitting around, going, “Nope. Nope. That’s good. Nope.”

That’s pretty much the story. I printed the logo on a bunch of T-shirts five or six years ago, and I gave those to a few friends as a joke shirt to wear to a music festival. It’s been great—other people, like Xminus1, who used to live in Seattle, and now lives in Minneapolis. Especially since this is our second Sketch Artist release, I joke that it’s the unofficial Sketch Artist label.

My production work interfaces with that anxiety more, and especially my ‘sighup’ work. That was me primarily using music from the Islamic Republic. I didn’t have any connection to this, because I didn’t grow up there, but I experienced racism, ridicule, and associations with terrorism when I was younger. It was me being, like, “Okay. What if I was associated with that?” I grew from that, because it was a bit of an edgelord project. But, with the ambient stuff as ‘nohup,’ I drew upon [traditional] Persian music. The question, there, was, “How can I bring this into the story of myself?”