Please support Passion of the Weiss by subscribing to our Patreon.

Bedroom Beats & B-Sides: Instrumental Hip-Hop & Electronic Music at the Turn of the Century will be released November 6th. You can pre-order it here.

Author’s note: The following chapter is the first of three focusing on Los Angeles and its significance to modern beat culture, and it aims to give an overview of the roots of LA’s beat scene from the late 1970s to the early-mid 2000s (the other two chapters focus on the mid to late 2000s era). The chapters in the book are formatted as beat tapes, with the intention to use the format as a way to move through narratives more freely and, hopefully, evoke something of the music in the writing. What this means in practical terms – especially if you’re reading this extract and nothing else – is that each sub-section of the chapter is titled after a beat/track/song prefaced by // and followed by the name of the producer. These titles act as both markers for shifts in the narrative and as a way to make your own soundtrack to the reading. Notes for attribution and citations can be found at the end under Sample Bank, any non-attributed quotes are taken from interviews I conducted.

Close your eyes and picture Los Angeles. Whether lifelong resident, transplant, or visitor, we all have an image of LA in our heads, perhaps even a mental map of the city. Be it drawn from experience, expectation, or entertainment; this map rarely matches the reality of an urban space that defies traditions and, for many, understanding[1]. As the writer, urban theorist, and Southern California native Mike Davis put it in City of Quartz, “Los Angeles may be planned or designed in a very fragmentary sense (primarily at the level of its infrastructure) but it is infinitely envisioned.”

I first visited in January 2013 and returned yearly before moving here in 2017, living in different neighborhoods and adjacent cities over the past three years. Coming from Europe, the miles-long boulevards, invisible boundaries between cities, and lack of public space made for a jarring sensation that took a while to absorb and rationalize. The enduring feeling is that you could spend your life here and never get to the bottom of what LA has to offer. And yet LA makes it relatively easy for anyone to participate, in fact it invites you, and it has long been a refuge for those with a creative bend. “I never felt as compelled to create anywhere else,” said Brian Cross, who relocated from Ireland to California in the late 1980s. Other cities got in the way of Cross’ creativity but LA gave him space to do constant work. “I think that experience is one a lot of people have here.” I’ve felt it too just as I felt it when I lived in Tokyo, another city on the edge of the world where European conceptions of what an urban space should be, and how people should behave in it, are challenged. “Madlib always talks about ‘We don’t know when it’s going to run out,’” Cross continued. “And we don’t. Human creativity is a fragile thing but [LA] is an inspiring place and it has a very peculiar and interesting mixture of people.”

The most common experience of LA is as a series of interlocking private spaces, bodies shifting between houses, strip malls, offices, and cars. It’s perhaps the most commonly understood, and criticized, aspect of the city. Even the streets, which should be the one available public space, can feel private. They’re often hard to navigate and strewn with pieces of private life – mattresses, tables, chairs – as if someone’s home had just been emptied out, forcing you to step inside. In LA, the private is where the public and collective is imagined. It’s the same logic that drives the city’s best-known entity, Hollywood.

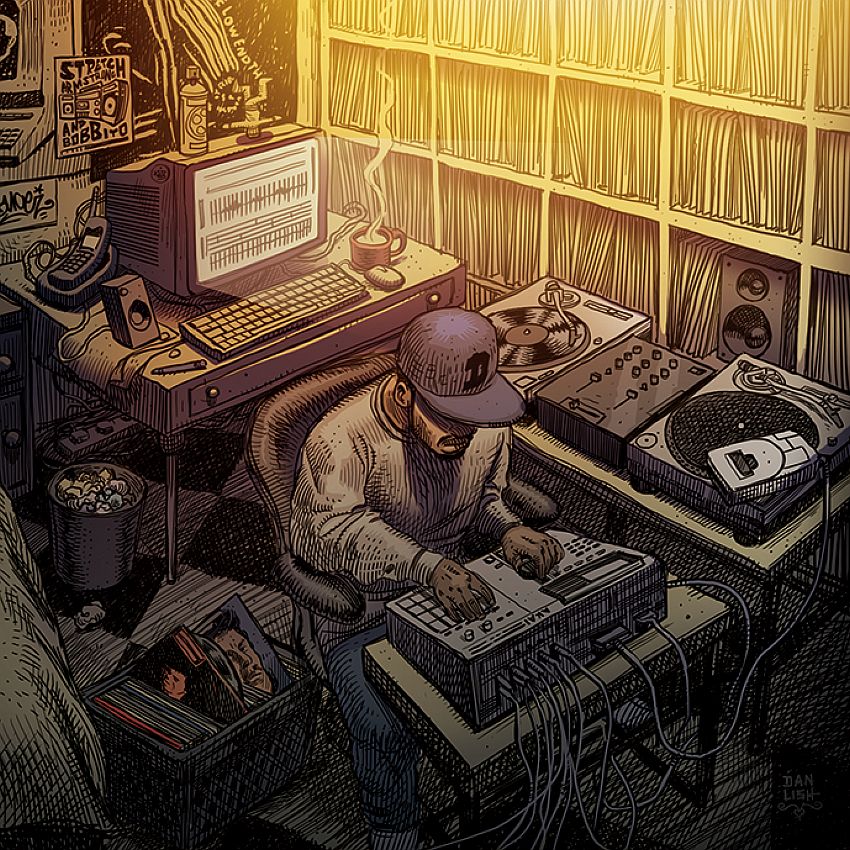

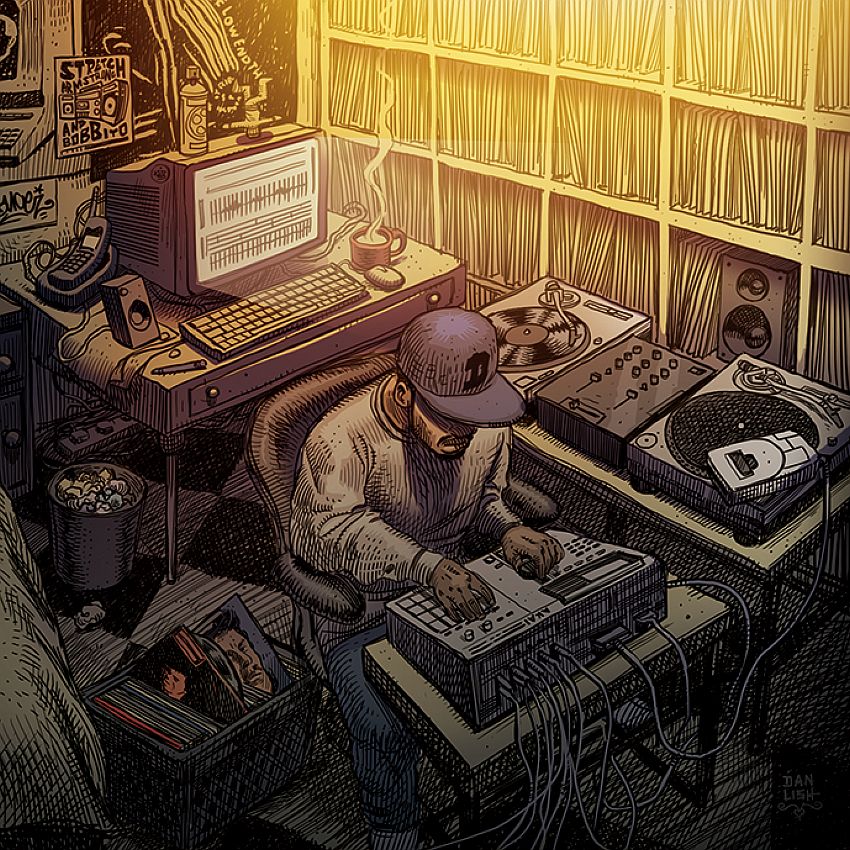

“It puts us in the same city with a bunch of people that are in the business of finishing things,” said Cross. “And somehow by osmosis that’s the measure out here. Did you finish it? Is it done? Can I see it? Where is it?” This attitude combines with another characteristic trait of the city’s residents. “We’ve a terrible reputation for being flakey but it’s because people build their nests here and they don’t want to leave them. And it’s a hassle to leave it. So you get this situation where it’s perfect for bedroom studios out here, you can get a cheap place to live that has plenty of space. You don’t have to leave the house.”

// Beatronic (Ghetto Blaster Mix) [Unknown and Three D]

LA’s rise as a stylistic center for hip-hop in the late 1980s and early 1990s made it a worthy rival to New York City, a fame that overshadowed its contributions to modern beat culture and left it on the periphery of our story until the 2000s. Mapping the roots of LA’s contributions to beat culture is not unlike driving around the city. It involves detours, dead ends, and a desire to get lost in order to find something you didn’t know existed. These roots stretch back across decades and the entire urban sprawl that makes up the mental image most people have of the city. The full scope of such a journey is beyond the limits of this book[2], but we’ll attempt a short version of it in this chapter as many of its elements are foundational to LA’s ascendance in the first decade of the 21st century as the home for a new generation of beat heads.

It would be foolish to claim that there is a single inception point to the history of LA’s beats. Instead, like all the best things about this city, it is a product of a diverse mix of people, ideas, and influences. The electro sound of the 1980s is the most appropriate entry point into the maze. LA got in on the act thanks in large part to the enterprising spirit of two DJ crews and promoters who created a foundation on which other parts of the city’s nascent hip-hop infrastructure was built: Uncle Jamm’s Army and The World Class Wreckin’ Cru. The former were led by Rodger Clayton and Gid Martin, and at its height could lay claim to being the biggest promotion team in the United States, a supercharged version of the popular mobile DJ crews of the time. The latter was the brainchild of Alonzo Williams and the launchpad for the careers of Andre “Dr. Dre” Young and Antoine “Yella” Carraby. In both cases, these collectives turned bedroom DJs into local, and eventually international, stars and released records that spread their sound, notably via Techno Hop, the label of Wreckin’ Cru affiliate Andre “The Unknown D.J.” Manuel.

Radio also played an integral part in these early years. In 1983, local AM station KDAY pivoted to hip-hop under the direction of its new music director, Greg Mack. A transplant from Houston and “proud country boy”, Mack quickly educated himself about LA’s party scene. When Uncle Jamm’s refused his offer to join the station he instead brought on Dr. Dre and Yella to provide mixes, the first step to creating his own Uncle Jamm’s inspired collective, the KDAY Mix Masters[3], and turning the station into a national rap leader. The electro sound and the skills of local DJs to blend it with funk, boogie, and rap provided an evolving, intricate soundtrack to car rides, backyard happenings, and nights out. Soon enough, LA was on the same wavelength as other DJ and beat-centric hubs of the time like Miami, Detroit, and NYC. And for the generation that grew up listening to them, nothing would be sweeter than a perfect beat.

// Arhythamaticulas [Chillin Villain Empire]

As for hip-hop there’s perhaps nowhere more important as a starting point to our story than the Good Life Health Food Centre, located on the corner of Crenshaw and Exposition in South Central, a few miles west of Exposition Park where Uncle Jamm’s once held its legendary takeover of the Sports Arena. The Good Life was a family business owned by Janie “Ifasade” Scott-Goodkin and Dr. Phillip Walker, known as Omar. The pair sought to bring the benefits of holistic health to the neighborhood while also creating a welcoming space for all. In December 1989, as they neared the official opening of the store, the owners began to plan a schedule of nightly entertainment.

Their friend Bee Hall, who ran a local nonprofit youth organization, suggested they include hip-hop to help invite young people into the space. Hall’s son, R. Kain Blaze, and two of his friends developed the concept for the night, originally titled Underground Radio Live, as a hip-hop showcase with an open mic. The idea was to create a space for artists away from the more distant hotspots further north in Hollywood. The first night attracted six people. Within six months a hundred showed up. And by 1991 there were 300 eager hip-hop fans and would-be artists trying to cram themselves into a space that only held 75 at a push, eventually spilling out onto the parking lot where the action could be just as intense and exciting as it was inside.

This weekly Thursday hip-hop night and open mic session eventually became synonymous with its locale, now known as the Good Life Cafe and still remembered by many as simply the Good Life. The early 1990s were a tumultuous time in South Central LA and its adjacent cities: on one side there was systemic racism, police brutality, and social upheaval[4]; and on the other a new-found global fame as the epicenter of gangsta rap thanks to the commercial success of N.W.A and its members. The Good Life was an oasis amid this chaos and over the course of four years it grew into the focal point for LA’s own alternative hip-hop scene with a community-minded and DIY approach that upheld positive behavior, respect, and freeform creativity. Instead of gangsters and bitches, you’d find wheatgrass and lyrical calisthenics. Hip-hop in its raw, unprocessed form, molded into anything the mind could think it to be. As the reputation of the Good Life as a cultural hotspot spread it began to attract all sorts of interest from industry A&Rs looking for talent to poets, actors, thinkers, and a TV producer who’d drop his kid there regularly and took inspiration from it for similes that appeared on shows like Moesha and South Central.

While the Good Life is best remembered as a rap institution, from which beloved groups like Freestyle Fellowship and Jurassic 5 emerged[5], it was also somewhat of a playground for producers. The first notable name to emerge from it was Chillin Villain Empire (CVE), a collective of rappers and producers whose sonic contributions to the night and its attendant scene are notable though little-known outside of LA and dedicated fan circles. “Their beats were so distinctive and unique, you knew a CVE beat when you heard it,” recalled Ava DuVernay, who at the time was an aspiring MC within the duo Figures of Speech and whose debut documentary This Is The Life told the story of the open mic session. Working out of the CVE Shack in South Central, the crew had range – from jazzy to smooth, rugged to futuristic – and they provided a regular soundtrack to the Good Life with their homemade beat tapes[6]. “Their production was interesting, sounded southern,” recalled journalist Joseph Patel. “We’d heard Outkast in 1993, 1994 and my brain was like, ‘Freestyle Fellowship would get along with Outkast or Goodie Mob.’ The Pharcyde and CVE were an exception to the quality of beats in LA and CVE were the first ones to try and make music to match the lyrics.”

// Strength of A.T.U. [Fat Jack]

By 1994, the Good Life had outgrown its humble origins. The small stage could no longer accommodate the large community it had fostered. Instead of dissipating, the energy and intent moved down the road to Leimert Park, which since the 1950s had grown into the city’s cultural center for the Black community, and one of its most important neighborhoods. The Good Life became Project Blowed, finding a new home at KAOS Network, in the shadow of Leimert’s most iconic building, the Vision Theater. Located around the corner from noted jazz venue The World Stage, KAOS was a community media lab opened in 1990 by Ben Caldwell, a teacher, entrepreneur, and activist who had worked as a cinematographer and writer as part of the Black independent film movement known as the LA Rebellion. The new space offered a bigger stage and better equipment for the weekly open mic session and workshop, attracting hungry young talent under the vigilance of Caldwell and Good Life veterans.

Another thing that carried over from the Good Life to Project Blowed was a practice some attribute originally to CVE: selling cassettes of beats for MCs to practice to. CVE members Ebow and Omid Walizadeh, a Chicago native who lived in Long Beach, sold their tapes to willing attendees outside Blowed for $5. For many it was their first encounter with beats in a raw form. The producers needed the MCs and vice versa but for some of the younger heads, including those who wanted to become beat makers themselves, the beats were attractive enough on their own. James “Fat Jack” Clark made his name in the early years of Blowed, both as the producer for Abstract Tribe Unique and a purveyor of dope beat tapes. “Fat Jack, he was the dopest producer out of Blowed to me,” said Gregory “Ras G” Shorter, who cut his teeth as a DJ and producer at Blowed. “Shit he was doing for ATU was what I most gravitated towards out of any of it. “Strength of A.T.U.”, that beat still crazy. That was my favorite crew out of Blowed. They had the voice, the beats, the vibe. It was it to me, it’s where I was at with it.”

As the decade progressed, the range and style of producers attached to LA’s independent hip-hop scene grew. There were older heads like CVE and Jurassic 5’s Lucas “Cut Chemist” McFadden and Mark “DJ Numark” Potsic. The latter pieced their beats together with the same obsessive, breaks-driven, loop-digging quality as DJ Shadow and found international success with their group in the early 2000s. And then there was a growing new school developing their own take, bridged by Omid and Fat Jack who’d had a foot in both the Good Life and Blowed: The Nonce, the rap and production duo of Nouka “Sach” Basetype and Yusef Afloat; Aaron “Elusive” Koslow; jazz musician Josef Leimberg; Matthew “Mumbles” Fowler; and Ras G and his friend from Watts, Donell “Dibiase” McGary. Just as N.W.A and Dr. Dre had helped change the sound of hip-hop at a mainstream, commercial level, the Good Life and Project Blowed provided a dynamic engine for constant exploration for those who were still operating out of their bedrooms.

For Regan Farquhar, the Good Life and Blowed represented “the premier epicenter of underground hip-hop in California and in the United States at the time.” Farquhar first began attending the Good Life in 1992, at age 14, before cutting his teeth as Busdriver at Blowed and starting his career in the 2000s within the city’s alternative hip-hop and electronic scene[7]. “I was very enthralled by it, it has informed and absorbed my creative efforts ever since. As I found out, periodically in LA with the types of music that I’ve been associated with, they become these hotspots, these epicenters where the small idea gets momentum and becomes a burgeoning influence. I’ve seen it happen over a few years and when I went to the Good Life that was the first time that I witnessed something that was translating beyond me, that was happening in my local city.”

The DJ spirit celebrated by the likes of Uncle Jamm’s and KDAY in the 1980s transformed into a tapestry of weekly, monthly, and irregular parties throughout the following decade. A new breed of selectors rose up across LA, with a common theme of connecting eras, styles, and sounds rooted in rhythm by using their records as well as live musicians.

Some styled themselves after sound systems, others as DJ crews, and yet more simply used the name of their party: there was Umoja (Swahili for “unity”), founded in 1992 by Tomas Palermo and Daz as a jazz and reggae club night at the Martini Lounge and which expanded into the wider Umoja Soundsystem; the Beat Junkies, formed in 1992 in Orange County, south of LA, by Jason “JRocc” Jackson, a group of turntablists and radio DJs who replaced the Mix Masters as essential listening in the 1990s with shows on new FM stations Power 106 and 92.3 “The Beat” as well as through mixtapes and live performances; the Soul Children, brainchild of Qmichelle, Sacred, and Al Jackson who took on a mission of creating a “soulful experience” first as the Underground Railroad and then with the Brown Rice N’ BBQ parties before launching the itinerant Juju in the early 2000s; Firecracker, a genre spanning night co-founded by Eric Coleman which took residency at the Grand Star Jazz Club in Chinatown, in the shadow of Bruce Lee’s statue; J Logic’s hip-hop minded Sound Sessions at El Cid; the Proper crew, featuring Rashida who in 2004 began a ten-year stint as Prince’s tour DJ; and the Root Down which took up residence at Gabah in 1997 under the auspices of Miles “Music Man” Tackett and Carlos “DJ Loslito” Guaico, a party where fuzzy breaks and original samples reigned supreme spawned from a previous series called The Breaks and home to live band The Breakestra.

“Root Down was one of the reasons why I moved to LA too, and Firecracker,” said Stones Throw’s founder Chris “Peanut Butter Wolf” Manak. “I was used to where it would just be a hip-hop night or be a house music night, but with those they integrated Afrobeat, reggae, hip-hop, 1970s breaks, 1980s boogie. It was everything. And that was just what I always wanted in a club at the time[8].” Remembering his early encounters with the Soul Children’s parties, where alcohol was replaced by healthy “elixirs”, Brian Cross mentioned the uncanny energy that could be found there.

“You’d get in the zone and the music would come hard. They had their own crowd too, a particular generation of cats from South Central. Sometimes the sound system would break down but then fools would clap for twenty minutes. And next thing you don’t even need a sound system, it’s like samba school. A key factor in this country is the Black public sphere, it’s where magic happens, because it’s not about listening anymore. It’s participatory, there’s a spiritual element, it’s ancestral worship.”

// Looking For The Perfect Beat [Arthur Baker]

Dance music ran parallel to LA’s independent hip-hop world. As the 1990s hit, the rave scene moved from the fringes of warehouses, backyard parties, and outdoor events towards clubs. A key catalyst throughout the decade was Urb, a bi-monthly alt publication dedicated to club culture which also covered hip-hop. It was founded by Raymond Roker, a mixed-race immigrant from Barbados who turned an early interest in graffiti into a passion for design and documentation with the arrival of home computers. Due to financial necessity, Urb’s approach was DIY but its ragtag charm endeared it to both fans and artists. By 1997, it had stepped up from 3,000 copies distributed locally by hand to 50,000 available across the country, making it the United States’ largest publication dedicated to dance music culture.

Roker wrote regular columns for the magazine and in 1996 he recounted a recent trip to the South Bronx, where he went seeking answers from Afrika Bambaataa. “He, of all people, could help illustrate some of the parallels that I believed existed between hip-hop and dance music culture. I wanted him to support my argument that these self-exiled tribes existed only in the polluted ocean of prejudices. He did. For five years I have been of the mind that we are one. We are a tribe squeezed out of the street, one that has taken root across the globe in a multitude of forms.”

// Soundstorm [E-Sassin & R.A.W]

One particular dance music sound LA developed a taste for was breakbeat techno, and its eventual mutation into jungle. Raoul Gonzales, a hip-hop and electro DJ, renamed himself R.A.W (Rules All Warehouses) in the mid-1990s and became an early champion of the music alongside another local Latino kid, Oscar Da Grouch. As the music turned into drum & bass, Roker and promoter Chris Vargas launched a new club night called Science in 1997, followed two years later by another couple of breakbeat weeklies: Respect, held on Tuesdays in Hollywood, and Konkrete Jungle, on Wednesdays at Spaceland in Silverlake[9].

Konkrete Jungle was organized by Kevin “Daddy Kev” Moo and Michael “DJ Hive” Petrie. The two were roommates at the time and involved in the hip-hop scene with their label, Celestial Recordings. Through Hive’s connections to Project Blowed, the label released records from rappers and producers attached to the weekly event – including Fat Jack and Omid. Hive meanwhile produced records that evolved from instrumental trip-hop to a blend of hip-hop and drum & bass. The connections between the two genres were central to the work of many of the protagonists in the LA scene, who identified a hip-hop futurism in the sped-up breakbeats.

“We were trying to illustrate the connection between hip-hop and drum & bass,” said Moo, who also invited local rap MCs to Konkrete Jungle including Freestyle Fellowship’s P.E.A.C.E and Myka 9. “Arguably we were the only drum & bass guys working with real hip-hop MCs. So people like Freestyle Fellowship and Supernatural. Really trying to do songs that had hip-hop style arrangements but with drum & bass tempo and its sonic aesthetic. It was interesting.”

Another MC who fell into this mix was Busdriver, who spent hours oscillating between the party’s two rooms – one for hip-hop and the other for jungle and drum & bass – learning and practicing. “You’d have to follow and abide by the rules of both rooms. Mix and match. I learnt a tremendous amount from that period. Rapping for hours on end, it was very formative.” The MC saw little difference between his experiences at Konkrete and Blowed. “There was an emphasis on different proceeds, different things were brought into focus.” The beats, regardless of their tempo or style, provided a foundation that both MCs and producers could tap into to explore possible futures.

LA’s vastness is often seen, and felt, as a driving force for social atomization. In fact, it also acts in an opposite way, as a force for community. “[LA’s] sprawl is the perfect ecosystem for little nodes to pop up,” explained Mark “Frosty” McNeill, an Austin native who moved to LA in 1994 to attend university. “That space allows for people to at once be very apart but be very together, because they’re connected through all these routes.” In the 20th century, intangible radio airwaves were the most common routes leading to physical nodes such as parties or record stores. With the advent of the internet, some of this traffic began to move online with a similar end result of finding yourself in a space where you could connect with others.

College and commercial radio stations provided LA’s alternative scenes with a degree of support. But they also remained in competition for listeners and isolated specific sounds among wider programming needs. The first LA station to change this was dublab, which began broadcasting online in 1999. dublab was born from the ashes of KSCR, the University of Southern California’s station which operated without a license, a pirate with a signal covering mostly downtown, parts of the northeastern hills, and a good stretch of south LA. By the mid-1990s it was staffed by a group of students with a penchant for electronic music, hip-hop, and their foundational sounds. The students’ eagerness attracted both visiting artists, including British drum & bass DJs and NYC rap acts, and locals such as JRocc, Cut Chemist, and R.A.W. Within this group were McNeill and his brother, Alfred “Daedelus” Darlington, a jazz student, DJ, and aspiring producer, and Edward Ma, a transplant from Boston who became a resident at Konkrete Jungle and made beats as the Con Artist. Alongside radio they threw parties, creating a thin but strong mesh between the various scenes they were all a part of.

In the spring of 1998, the students discovered the university’s RealMedia server and convinced the administration to let them use it for broadcast. A few months later the Federal Communications Commission shut down the university’s illegal FM transmission. With a new status quo and the end of their degrees approaching, the group decided to focus on the internet as a way to keep doing what had become an important part of their lives. In September 1999, McNeill and John Buck founded dublab, the name a portmanteau of dubbing and laboratory, terms that spoke of replication and experimentation. Their roster of DJs was pulled from the city’s existing stations – KSCR, KXLU, and KPFK – and their connections to various scenes.

“We brought those radio bodies together, and people who were on a similar wavelength but that also connected with different club DJs and people who were active in different weeklies and clubs around LA,” said McNeill. “And we started this new thing and it was cool. We didn’t know what was going to happen, but we were able to put together a really great schedule of DJs that was bridging a lot of different ground. It was a cool umbrella situation.”

dublab quickly became a place where DJs and artists could put copies of their bedroom experiments and discoveries directly into people’s ears. Unlike other early internet stations that appeared off the back of the first internet boom, it was set up as an LLC with the intention of using the profits to benefit the community. The station never really made any money, relying instead on listener support and ad-hoc sources[10]. The lack of commercial success didn’t stop it from quickly becoming a space – both physical, in its studio and events, and digital, in its broadcasts – where the city’s diversity could be celebrated and allowed to grow. “[dublab] represented the first non-moneyed entity to enter the scene,” said Daedelus[11]. “It didn’t have a hat in any race, no say in things, just about music culture. It was an exciting time. The internet was forming as a voice. We didn’t have a concept of sharing music online yet. It was just really traditional radio with a bigger reach.”

The foundational spirit of dublab was represented in its first compilation, 2001’s dublab Presents: Freeways, released on local electronic and hip-hop label Emperor Norton. With a wide mix of local artists – including Madlib’s jazz project Yesterday’s New Quintet, dance music producer John Tejada, hip-hop veteran Divine Styler, singer Mia Doi Todd, Dntel (soon of The Postal Service), drummer Adam Rudolph – Freeways captured some of the cultural and sonic routes that criss-crossed the sprawl and established dublab as a new intersection, a connecting node rather than just another stop on its many roads.

// Agent Orange [SA-RA Creative Partners]

In July 2003, Rawkus Records released “Agent Orange”, a new single from Queens rapper Pharoahe Monch. The politically charged song, full of subtle wordplay about American warmongering and terrorism alongside some not so subtle turn-of-the-millennium paranoia, was a perfect display of the lyrical dexterity and careful delivery that had made Monch a darling of the East Coast rap scene. The single was catnip to the backpack school of fans who wanted more from the rapper, yet for some the beat was the real star of the single: loose, off-beat drums, languorous guitar licks, and a deep, free-form bassline that in its modulation and slight staccato managed to match the horror Monch was referencing in his rhymes[12].

The promotional banner on the “Agent Orange” 12″ listed the track’s producers above the song title: SA-RA Creative Partners. This was the second official credit to appear under that name, the first being Jurassic 5’s “Hey”, a mellower, laid-back funky joint on the group’s 2002 album Power In Numbers. At that point little was known about SA-RA Creative Partners but there was a dexterity and feeling to the music that betrayed a deeper experience and spoke of the infinite expanse and possibilities contained within beat culture.

// Negative Ion (Sa-Ra Mix) [SA-RA Creative Partners]

Shafiq Husayn was working in a studio in LA in 1999 when his friend Taz Arnold came over with a beat CD. The pair often spent time listening to and discussing music, what Husayn called “appreciation classes” between friends. But this beat CD hit a little different. It was from Detroit producer James “Jay Dee” Yancey and after hearing it Husayn immediately decided he needed to move on from where he was at musically and professionally. There was something in Jay Dee’s programming that reminded him of earlier lessons about the importance of timing and feeling. Hearing these beats and the way in which they challenged the accepted precepts of hip-hop production convinced him that this was the way forward, rather than the tired clichés of boom bap and commercial hip-hop that were dominating at the time.

“When I heard [these] tracks I was like, ‘Damn he went all the way in,’” Husayn recalled. “Soon as Taz played it, in my mind, in my heart, I was like, ‘I can’t make music where I’m at anymore, this space won’t allow me to do what I need to do.’” The next day Husayn quit the group he was in, Nile Kings, and with Arnold and another close friend and collaborator, Om’mas Keith, set about developing the concept for a production outfit that could embody the same progressive aspects of hip-hop production he’d heard in Jay’s beats as well as represent “infinite opportunities.”

The name they settled on was Sa-Ra, two words borrowed from ancient Egyptian language – Ra for energy or god or universe, and Sa meaning of – which they flipped into the “offspring of the most powerful energy in the universe.” The name spoke of their own interests in the histories, cultures, and spirituality of Africa and of their desire to move forward into the future of the music. “If you’re saying your group is [the most powerful energy in the universe] then your music in some way has to be some type of representation of that. In some form. That’s the seed. The three of us, all three lords from three separate worlds, as we used to put out there. We would explore any and all avenues in music in our private times, and that’s the birth of Sa-Ra.”

The eldest of the three, Husayn was born in Cleveland, Ohio and raised between LA and NYC. He first became involved in hip-hop as a DJ in the orbit of the Zulu Nation before meeting Ice-T at an Uncle Jamm’s Army after-school show. Soon after this meeting, he became part of the rapper’s production entourage just as Ice was ascending to national fame. That connection led to his inclusion in the Rhyme Syndicate collective, the Nile Kings (in which he also rapped), and various behind-the-scenes production work.

Arnold is an LA native who looked up to Shafiq as an inspiration and first connected with him in the late 1980s. Starting out as a dancer, by the late 1990s he was dabbling in production but his main gig was management and consultancy, most notably for Dr. Dre’s second album.

Om’mas Keith is the youngest of the trio, born in Brooklyn and raised in Hollis, Queens. The son of a jazz singer and trombonist, Keith had originally wanted to be an attorney but, as his parents knew, was always destined for a life in music[13]. He learnt to play the drums at an early age and spent his childhood studying music and meeting jazz greats – Sun Ra, Weldon Irvine, Gary Bartz – before following the siren call of hip-hop. He landed some early production and engineering credits in the mid-1990s NYC rap world, which led him to work with Run DMC’s Jam Master Jay and also cross paths with Husayn in LA. The two hit it off and spent some time living and working together in Harlem a few years later. After Husayn moved back out west, he introduced Keith to Arnold. Operating on their own, and sometimes together, on both coasts, the three remained in contact as they accumulated experience and deeper connections throughout the industry.

// Glorious [SA-RA Creative Partners]

It was during their time living in Harlem that Keith had turned Husayn onto the idea of unquantized beat programming, challenging his reliance on the clocks of machines and tapping into a looser, more human feeling. It happened one day during an impromptu session in their makeshift studio, as Keith put together a cover of D Train’s “You’re The One For Me” that they would play live. He made some drum sounds on a Roland SH-101 and jammed a sequence together.

“The drums, at the time to me, it was so live and no quantize, I thought it was off beat,” Husayn recalled with a laugh. “‘Cos I can actually hear it, it’s off. I’m like, ‘That’s off, Aki’ And he was like, ‘Nah what you think, that’s a live drummer, what you think a live drummer would do?’ I’m sitting there like, ‘Ok.’ After a while I got it ‘cos I couldn’t fight the logic. But it felt different.” Soon enough Husayn was on board with the idea, what Keith called “the slop,” and this simple moment of shared knowledge in the studio would in turn feed Husayn’s own evolution and lead to the birth of Sa-Ra a few years later.

When the time came to act on the conversations Husayn had been having with Arnold and Keith, it was obvious that it had to be the three of them together. They each brought something to the table that made the sum total greater than its parts. Together they covered production, composition, engineering, mixing, business, and fashion. They first joined forces in 2000 but it wasn’t until shortly after 9/11 that they really kicked into gear[14]. Keith moved to LA and the three of them commenced work in an apartment on 54th and Crenshaw.

“One room, keyboards, equipment and chess,” explained Husayn. “I’m working at the post office and bouncing in Hollywood. Om’mas is a teacher at the Musician Institute up in Hollywood, and Taz is still living off the Dre demos.” The full name of their outfit, SA-RA Creative Partners, was a nod to Keith’s stint at an advertising firm in NYC, a way to underline the inherent partnership in their endeavor while also aspiring to a certain commercial success.

“We came up with this name, SA-RA Creative Partners, which is like an amalgamation of the worlds of the spirit, the mind, the love, the sex, the freak and the business,” explained Keith. “[When I worked in advertising] I always noticed how all these firms that we used to deal with had the word Creative Partners in the name. It was really weird. […] I wanted to make sure that no matter what we did that we were in it to win it. We was going to feed our families off of it. We was going to do whatever.”

At first the trio made music for themselves, experimenting and having fun while searching for the essence of a new sound. From those early sessions they put together some beat CDs and in 2002 Taz Arnold took a trip to the Midem trade show in Cannes, France, where the industry met yearly, CDs in hand.

“He took our fucking CDs out to Midem and started passing them around,” said Keith. “Within three months of Midem, our shit was on the radio in the United Kingdom.” This early support came from fellow London beat heads including Attica Blues’ Charlie Dark and radio DJs Gilles Peterson and Benji B. “This is a time pre-internet,” continued Keith. “Our CDs started circulating around. People made copies, sent them to their friends and said, “˜This is some trippy shit. Listen to this.’”

The CDs also made the rounds locally in LA where one ended up in the hands of local promoter and radio DJ Carlos Niño. “The beat CD had a phone number on it, I called the phone number, ended up over at their place right away and was listening to stuff and was all about it,” Niño recalled. “It was amazing.” A natural connector plugged into various corners of the LA music world, Niño invited the trio to perform live[15].

“[Carlos] was the first one to get Sa-Ra on stage for a live show,” said Husayn. “That was 2003. We weren’t even a group, we hadn’t decided to be a group yet, we were still producers trying to change the world musically. And Carlos persuaded us to get on stage as ourselves and perform all these demos he heard. And that’s the birth of Sa-Ra as a group, performance wise. So SA-RA Creative Partners was the production company and then Sa-Ra the group.”

Even though they’d imagined themselves as more of a traditional behind-the-scenes production outfit, the move to the stage wasn’t that big of a leap. “Some of the tracks [we would send out] at that time were a little unorthodox,” explained Husayn. They would often demo the songs for artists, showing how they could be sung or performed.

By 2004 Sa-Ra were playing both angles. They were producing under the Creative Partners moniker, including remixes for The Neptunes’ N.E.R.D project, and releasing and performing their own demos as Sa-Ra with shows both at home and in Europe. Their first single, “Glorious + Rosebuds”, came out that summer on San Francisco indie hip-hop label ABB Records and later that year they put out a second single with another SF label, Ubiquity. These early tracks spanned the range of Sa-Ra’s ambition, from sultry to boisterous, grounded by provocative production and arrangement that brought to mind Parliament-Funkadelic just as easily as it did Jay Dee.

In December of 2004, Sa-Ra won the newly created John Peel ‘Play More Jazz’ award at the Worldwide Awards in London, an annual celebration of new music organized by Gilles Peterson. At the same time their talent was attracting a growing list of popular artists who passed through their LA home studio looking for beats and inspiration – Erykah Badu, Common, John Legend. The latter two were the first signees to Kanye West’s G.O.O.D Music imprint, set up in 2004 with Sony/BMG, and Sa-Ra entered discussions with West to join the label. Yet they still kept their ear to the underground, enlisting young local talent for their live band – including a rapper/singer named Ty Griffin and a bass player named Stephen Bruner – and collaborating with various independent labels and artists such as Japan’s Jazzy Sport and, closer to home, Daedelus.

“With the overground and the more commercial, that’s how you’re going to get your acclaim and you’re going to pay your bills,” explained Arnold. “But also, on the flip side you have the underground where a lot of new things are constantly spawning. New sounds, new ideas, and things of that nature. We’re always paying attention to what’s new to constantly reinvent ourselves and upgrade and keep our ear to the streets. It’s very, very important, not only as a producer but as an executive, because we are executives as well as artists and producers. We’re constantly looking for new talent. To contribute something to the underground when we draw so heavily from it, it’s a natural thing for us.”

// Lost & Found [Shafiq Husayn]

During the years I researched this book I often thought of Sa-Ra’s work in the 2000s as suffering from bad timing. Here were three producers marrying the sensibilities of modern beat culture with the spirituality and musicality of jazz and the sensationalism and freakiness of funk, while also making space for fashion, consciousness, and a business mindset. It was an incredible mix that few could rival at the time[16] and while it found some success it never quite breached the gates of mainstream visibility.

Their debut album for G.O.O.D Music, Black Fuzz, ended up swallowed by industry politics[17] resulting instead in the release of two full-lengths that collected work from throughout the decade, The Hollywood Recordings in 2007 and Nuclear Evolution: The Age of Love in 2009. Sa-Ra’s approach pointed directly to the late 2000s ascendency of Kanye West as a pop icon that combined similar elements (Taz was a frequent sight in Kanye’s entourage in those years) as well as to the arrival of a new generation of bedroom producers and beat enthusiasts.

And so perhaps timing is the wrong way to think about it, because even if you might feel like they didn’t get their due recognition publicly, they did achieve what Husayn had mentioned they set out to do: bring through powerful energy. “We were definitely ahead of our time when we started,” Husayn told me when I put the idea to him. He then reverted to the various artists Sa-Ra had collaborated with, many of whom went on to have successful careers of their own over the following decade: Ty Griffin became the rapper Ty Dolla $ign; Stephen Bruner established himself as a solo artist under the name Thundercat; and other collaborators like Anderson.Paak and J*Davey went on to work with Dr. Dre and write for various pop acts. The list goes on: Georgia Anne Muldrow, Chris Dave, Robert Glasper. “[Those acts] picked up [this energy] and kinda grew into that and that’s the sound that’s out right now,” said Husayn. “So Sa-Ra basically set up the environment to make something now that will become the past that will come out in the future. We created an audience, an atmosphere for ourselves.”

Sa-Ra’s work was a celebration of modern beat culture and, importantly, an attempt at connecting the then opposed worlds of underground and mainstream. In terms of beats their closest peers in that era were Jay Dee and Madlib. But where those two remained estranged from the mainstream, Sa-Ra managed to infiltrate it though perhaps not without losing their grounding. They demonstrated that the producer in the 21st century could be a beat maker as well as a composer, arranger, singer, and artist. They took their beats to the stage and made people move to them.

“The Sa-Ra shit, no one will ever be able to say anything bad about it,” said Keith. “I got out of the game with Sa-Ra, if you want to look at it that way, having made two very powerful creative statements, the Hollywood Recordings and Nuclear Evolution. If we never do anything again on that magnitude or never release a project, at least we did that. Right now, my daughter, who is 16-years-old, her friends in high school are like, ‘Your dad’s in Sa-Ra? Oh my God.’ I never would think anyone would even listen to what we did but I know it’s fly because we was talking about freak. Everything that you’re not supposed to listen to when you’re young is what we were talking about on these records. Naturally, kids are hearing it like, ‘Man, what is this shit?’ It’s like the vulgarity of 2 Chainz and Chief Keef with the positivity of Earth, Wind and Fire. It’s a very unusual mixture.”

Footnotes

[1] The city of Los Angeles as defined by its legal boundaries is a very different thing to what many perceive as Los Angeles, and which more closely resembles what is in fact the county of Los Angeles. For the sake of simplicity I’ll be using LA/city to signify the latter though I’ll make it clear when talking about specific cities both in and out of the county.

[2] Let’s just say, dear reader, that I tried going on the full journey and it quickly spiraled out of word count. Someone should definitely write it though.

[3] Which included Tony G, Jammin’ Gemini, Joe Cooley, DJ Battlecat, M-Walk, Ralph M, and Julio G.

[4] Epitomized by the beating of Rodney King in 1991 and the uprising that followed the acquittal of the

officers in 1992.

[5] The list of acts who passed through the Good Life is too long for this footnote, but you can start with those two and then visit the website for the This Is The Life documentary for a more comprehensive list.

[6] CVE members Henry Lee Owens, aka Riddlore, and Amierr Braton, aka NgaFsh, handled the majority of the early CVE output.

[7] His father, Ralph, was a writer and producer for film and TV. In 1985, he wrote one of the earliest hip-hop films, Krush Groove. It was after repeatedly taking his son to the Good Life that Ralph ended up replicating what he saw there on the TV series he worked on.

[8] The Breakestra were one of the first local acts that Stones Throw signed after its move to LA.

[9] The name Konkrete Jungle was borrowed from an NYC party founded in 1994 by Salmon McFarlane that was one of the first weeklies dedicated to breakbeat culture in the US.

[10] It eventually moved to a non-profit status in 2008 and continues under it to this day.

[11] Darlington actually fielded a call from John Buck while at USC and put him through to McNeill, thus seeding the relationship that would lead to dublab.

[12] Rawkus never released Desire, the album that “Agent Orange” was the single for. It eventually dropped in 2007.

[13] His mother had asked Sun Ra for a blessing while pregnant and he told her to name the kid Om-Ra, with the ra eventually replaced by the name of his grandfather spelt backwards.

[14] According to Husayn the beat for “Agent Orange” was made during that period, reflecting the inherent tension of the times.

[15] He also asked them for a theme song for his KPFK radio show, Spaceways, and as is discussed in later chapters plugged them into various other projects.

[16] Save perhaps Anti-Pop Consortium, whose member Beans was another early freak fashionista, but APC lacked the industry connections and experience that Sa-Ra had.

[17] Some of the promised genius of it did appear on Fonzworth Bentley’s ill-fated 2008 single “Everybody” featuring Kanye and Outkast’s Andre 3000.

Sample Bank

This chapter is titled after the 2001 dublab compilation released by Emperor Norton.

“Los Angeles may be planned…” Mike Davies, City Of Quartz (Verso, 1990). Davies’ book is an essential text for understanding the complexities, subtleties, and contradictions that make up the city.

“The former were led…” For more details on the fascinating story of Uncle Jamm’s Army and their peers see Todd Burns, “Nightclubbing: Uncle Jamm’s Army” (RBMA, 2017)

“Radio also played…” Details of Greg Mack’s work at KDAY are taken from a 2013 interview with All Hip-Hop

“The Good Life was a family business…” Details of the Good Life and its owners are taken from the following: Erin J. Aubry, “Positive Vibes: For Dedicated Young Rap Performers, Hip Hop Night at the Good Life Restaurant on Crenshaw Just Keeps Getting Better” (LA Times, 1994); Imade Nibokun, “A Special Reunion Show Celebrates The Legacy of The Good Life Cafe Open Mic” (LA Weekly, 2017); and the website setup by Ifasade’s daughter Erika

“Their beats were so distinctive…” Ava DuVernay in This Is The Life documentary (2008)

“By 1997, it had stepped up…” Details of Urb’s circulation and origins are taken from D. James Romero, “Dances With Words” (LA Times, 1997)

“He of all people…” ibid

All quotes from Om’mas Keith are taken from his 2016 Fireside Chat for Red Bull Radio

“With the overground…” Taz Arnold in SA-RA Creative Partners 2004 RBMA lecture