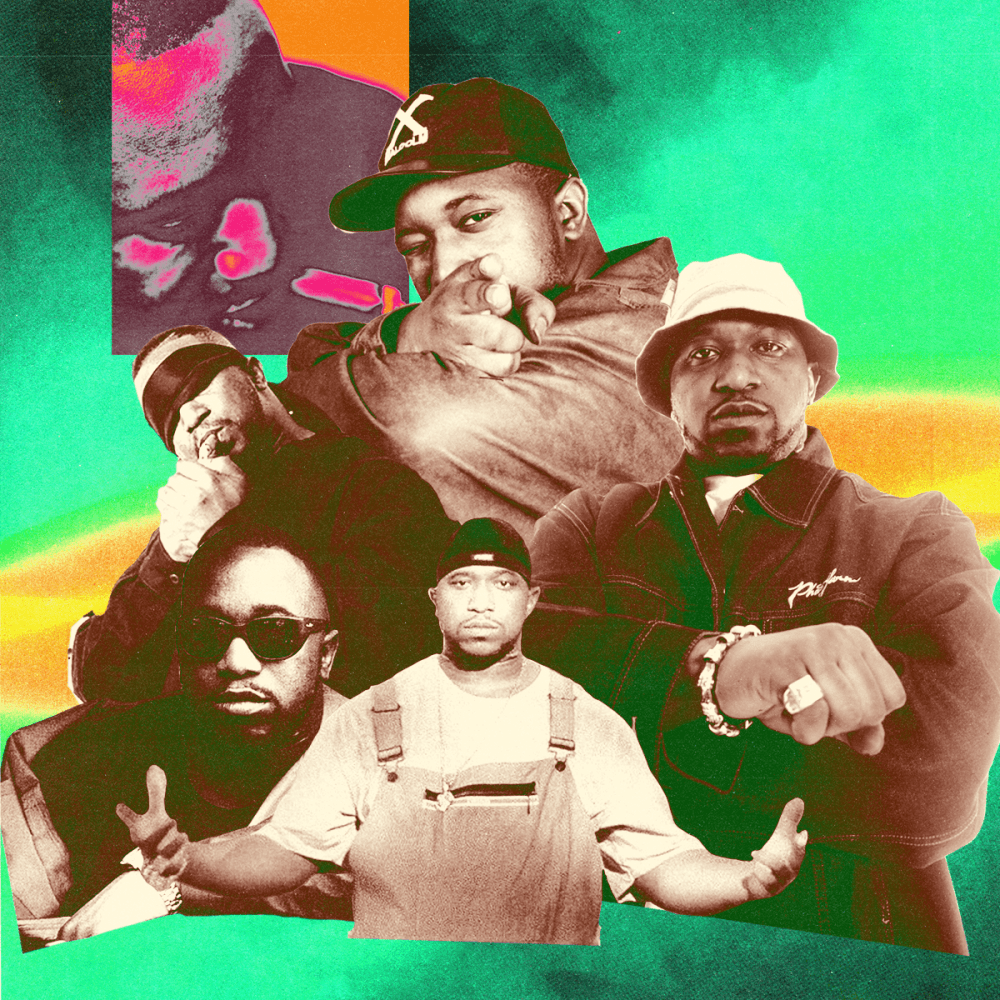

Art by Evan Solano

Jeff Weiss is gonna’ rock this at the drop of a dime.

Stars were born in the crumbling tenement on 12th Street. By the mid-80s, this roach-riddled, two-bedroom in the Queensbridge projects was the centripetal force of the hip-hop solar system. That’s where Marley Marl controlled the den of the dingy apartment that he shared with his sister, and whatever rappers happened to be rewiring music’s circuitry that night.

Sometimes, you could find Roxanne Shanté dozing at the kitchen table or Eric B sleeping on the floor. Big Daddy Kane, Biz Markie, and even Rakim arrived on the F Line to inhale breakbeats and exhale arson. If you were a nascent hip-hop superhero, this makeshift studio was the nucleus of the New York underground – the hidden centrifuge where MC Shan constructed “The Bridge” and Shanté masterminded her revenge.

One night in 1986, an 18-year old named Nathaniel Wilson from Corona, Queens, received his invitation to immortality. This wasn’t his first time in the booth. The Disco Twins gave the neighborhood kid a shot at making a record. So did Herby “Luv Bug” Azor, who was already producing and managing Salt-N-Pepa. But those initial fusillades went nowhere. So when DJ Polo brought Wilson to Marley Marl’s apartment at the height of the Bridge Wars, the young rapper kept his expectations in check. The song inside his notebook was modestly titled “It’s A Demo.”

Entering the colorless, carceral-looking tower, Wilson climbed the pissy stairwells to the second floor. Dim light scowled inside Marley’s laboratory. The four-track reel was running. The producer cued a sample loop of James Brown “The Funky Drummer,” and Wilson delivered a howitzer attack disguised as one of the best introductions in rap history.

People in the audience/Kool G Rap is my name

I write rhymes and insert them inside your brain

Polo and Marley instantly understood they were witnessing the future of hardcore. Within days, the DJ/producer started spinning “It’s a Demo” on Mr. Magic’s Rap Attack. By the time that G Rap appeared next at Marley’s studio, MC Shan and Fly Ty Williams (the impresario behind Cold Chillin’) were in rapt attendance. The latter offered a record deal. The Juice Crew, the most formidable collective in hip-hop, added a sicario capable of matching (or perhaps eclipsing) Kane bar-for-bar. It was like when the Golden State Warriors acquired Kevin Durant. The competition should’ve filed a formal complaint to the League.

The lopsided talent ratio became abundantly clear on 1987’s “The Symphony,” an idealized Juice Crew posse cut that Plato would’ve dreamed of in the cave if he had access to 808 drums and Otis Redding records. The still-teenaged G Rap rapped for so long and with such blitzkrieg fury that the tape reel slid off the machine. It’s the most indelible verse on what might be the most dominant performance ever delivered by a rap ensemble. The intricate syllable placement might as well be a polynomial equation mapped by John Nash. The machine gun staccato has no safety. G Rap was probably being humble: his voice was at least four times more horrifying than Vincent Price.

Conventional logic can explain Kool G Rap’s advancement of the art form. But I prefer to ascribe his scientific breakthroughs to more mystical origins. In the late ‘60s, the author Erich Von Däniken’s book Chariots of the Gods posited that the greatest achievements in human history – from the pyramids to the crop circles ¬– were the work of aliens. The alternate history hypothesized that benevolent extraterrestrials had gifted such futuristic technology to earthlings to enable them to take quantum creative leaps. In his autobiography, no less than fellow Paid in Full honoree, George Clinton, claimed that this theory helped inspire some of his most psychedelic odysseys on wax.

There is no proof that Kool G Rap was visited by an enigmatic species of interstellar creatures who bequeathed the secret of rapping at warp speed with surgical precision and the cinematic storytelling gifts of Scorsese. But it’s just as easy for me to believe that, as it is to heed the more terrestrial answer: that G Rap absorbed the wild style and meticulous craft of Melle Mel, Grandmaster Gaz, Kool Moe Dee, Spoonie Gee, and Silver Fox – and added his own blood and pavement poetry.

The eponymous first single from 1989’s Road to Riches essentially invented mafioso rap, the sub-genre later expanded upon by Nas, Raekwon, AZ, Jay-Z, Biggie, and Rick Ross. G Rap came out like Tony Montana went down: a guns-blazing, one-man, East Coast answer to N.W.A. The Source named his debut to its “Top 100 Rap Albums of All-Time” list. And these trife life sketches weren’t sensationalist caricatures. Listen to the cautionary tale, “4 Da Brothaz,” a harrowing chronicle of drug sales and inner-city violence, dedicated to a murdered 17-year old named Puzzle. More recently, Pitchfork named 1995’s 4,5,6 (the album “4 Da Brothaz” comes from) to its own best rap albums liturgy.

You can justifiably argue that any all-time ranking without 1990’s Wanted: Dead or Alive or 1992’s Live and Let Die is null and void. After all, the latter is basically the East Coast inversion of AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted – where G Rap decamped to Los Angeles to spit semi-automatic parables about organized crime, sex, and socio-politics over Sir Jinx’s hydraulic funk. Pharrell would probably argue this case. Nearly a decade later, the Neptunes producer’s studio session with G Rap largely involved trying to convince him to modernize “Ill Street Blues.” And lest you think that G Rap was limited to hard-boiled sagas, his “Erase Racism” treatise with Biz Markie and Kane preceded “Fuck Your Ethnicity” by two full decades.

If anything set G Rap back, it’s this sense of being too far ahead of his time. No singles charted near the Top 40. No albums went gold or platinum. Yet unlike many of his ‘80s peers, his catalogue doesn’t feel remotely dated.. Where even nominally excellent rappers sometimes operate in stylistic cul-de-sacs, G Rap’s complexity and imagination opened up a northwest passage for his predecessors to further explore. No rapper has ever been more respected or admired. There have never been any accusations of imitation; no false starts or contrived identities. Gimmicks or corny commercial compromises are anathema. This is rap as timeless as a snub-nosed revolver.

That’s why Scarface said, “I grew up on Kool G Rap…he’s one of the best.” Ice Cube called him “one of the most underrated lyricists in hip-hop.” Rakim declared “he’s all that.” The Roots first bonded over their mutual obsession with “Men at Work.” The GZA hailed him as an idol. So did Mobb Deep and Big L. On J. Cole’s “Let Nas Down” Remix, Nas prophesized that “G. Rap wrote the Bible.” On “Encore,” Jay-Z bragged that hearing him rap was like hearing “G Rap in his prime.” Whenever Action Bronson drew Ghostface comparisons, he insisted that the true patriarch of his creative lineage was rap’s reincarnation of Sam Giancana. As far as his most direct progeny, when Big Pun met G Rap, he literally kneeled to kiss the ring.

But the road to the riches was a labyrinth. Cold Chillin, the label that released the first four G Rap albums, was notorious for unpaid royalties. It didn’t help that Warner Bros declined to distribute Live and Let Die due to the backlash that followed in the wake of Ice-T’s “Cop Killer.” Then in the late ‘90s, amidst a G Rap resurgence, Rawkus Records offered a deal worth $1.5 million. But the label got bought, the release was delayed for years, and the underground Renaissance passed.

Only a few artists in history never fell off. G Rap is one of them. The notion of a lackluster verse is unthinkable. He’s 57-years-old and you can stick him in a cipher with the hungriest phenom that you can find, and you may as well start saying last rites for the rookie. His most recent album from 2022 is titled Last of a Dying Breed. But the title is only partially accurate: G Rap is a singular one-of-one originator.

On Saturday night at the Bellagio in Las Vegas, the Paid in Full Foundation is honoring G Rap alongside Grand Puba and George Clinton. Co-founded by Ben and Felicia Horowitz, the philanthropic organization includes Nas and Fab 5 Freddy on its advisory board and aims to reward the “most impactful original artists [who] never received recognition proportional with their exceptional contributions to arts and culture.” Through its grantmaking program, Paid in Full seeks to “honor the people who built Hip Hop…enabling them to pursue their creative and intellectual pursuits for the benefit of society.” In short, this is the hip-hop Genius Grant.

In advance of the event, I spoke to G Rap about his first memories of hip-hop, riding around with 2Pac during the L.A. riots, the making of “The Symphony,” taking Nas to shop his original demo, and much more. It was something like interviewing the inventor of the V-8 engine or the 9th Century Taoist alchemist who first created gunpowder. To this day, you can’t replace him.